Review Article :

Julie Niedermier*, Julie Teater, David Kasick, Maryam Jahdi

Objective: The goal of this study was to compare educational outcomes

of medical students who participated in a longitudinal pilot curriculum to

those who participated in the existing, traditional curriculum during their

third-year of medical school. Preliminary data from the pilot program is promising,

suggesting that the Lead Serve Inspire (LSI) curriculum may offer an equitable

alternative to the traditional discipline-specific block rotations. Medical

schools are constantly working to improve the quality and process of the

educational experience for students, often incurring considerable investment by

faculty, students and other stakeholders. Specifically, models of clinical

rotations for third-year medical students have been explored in great depth.

Existing research has compared outcomes of students involved in these different

models, including longitudinal integrated, hybrid, and block clerkships. Key

differences in student experiences and outcomes between discipline-specific block

rotations and the continuity of longitudinal, integrated, and hybrid clerkships

support the benefits of continuity in clinical learning. Specifically,

Teherani, et al. identified that students enrolled in longitudinal integrated

clerkships rated patient centered experiences; faculty teaching, feedback, and

observation; as well as the clerkship itself higher relative to students that

participated in hybrid or block clerkships. Yet, student performance on the

United States Medical Licensing Exam Step 2 (clinical knowledge) was equivalent

across models [1]. Results

support that integrated and continuous models are sustainable and generally

lead to improved or, at minimum, equivalent performances by students compared

to traditional rotations and may influence student choice of psychiatry as a career

[2]. Multiple lines of research support that longitudinal integrated clerkships

offer students important intellectual, professional, and personal benefits,

including better clinical preparedness, richer perspectives on the course of

illness, more insight into social determinants of illness and recovery,

and increased commitment to patients [3]. Additionally, longitudinal integrated

clerkships can be implemented successfully at a tertiary care academic medical

center [4]. These and other studies, including previous work from psychiatry and other

specialties, support that curriculum innovation may be valuable to students

overall educational outcomes. While

the body of evidence supporting the benefits of longitudinal integrated

clerkships is apparent, there remains a gap in the understanding of the

academic outcomes of students that participated in newer clerkship models.

Longitudinal clinical placements are underpinned by two central theoretical

concepts: continuity, and symbiotic clinical education [5]. In the review by Walters,

et al, the authors concluded that further exploration into the etiologies of

the transformational nature and effectiveness of newer curricular models is

necessary [6]. Existing

literature provides key insights about the optimal measures of assessing

curricular outcomes. Multiple miniinterviews for prospective medical students,

combined with preadmission cognitive indicators, have been shown to be

predictive of clerkship and licensing exam performance [7,8]. The process by which

medical schools identify, nurture, and transform prospective academically-viable

and interpersonally-capable students into skilled, patient-centered, and

resilient physicians remains rather elusive. It is amid this backdrop, that

there appears to be nationwide fervor to develop programs that can provide this

foundation. Likewise,

The Ohio State University (OSU) College of Medicine is in the midst of

curricular revision, namely with implementation of the Lead

Serve Inspire (LSI) program. This program

has fundamental differences compared to the existing curriculum, including

greater emphasis on clinical integration of specialties and longitudinal care,

as well as earlier exposure to patients. In addition, the revised curriculum

prominently features modifications to traditional learning strategies, such as

newer methods of content delivery, multidisciplinary presentations, and highlighting

critical appraisal skills. The LSI curriculum, itself, is unique amid an era of curricular

innovation, comprised of both longitudinal integrated and hybrid components. As

medical schools across the country are placing greater emphasis on newer modes

of learning, this study is undertaken to glean further data about the

implications for LSI in

psychiatric education.

Specifically, the purpose of this retrospective study is to compare the

clinical and examination performance of OSU medical students who participated

in a longitudinal pilot curriculum to those who participated in the existing,

traditional curriculum during their third-year of medical school. The

Institutional Review Board at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center

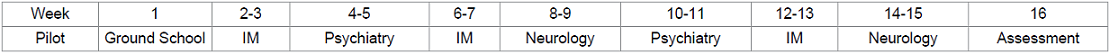

approved this study. The LSI curriculum for third-year medical students was retooled and

positioned to occur as part of a combined experience involving the disciplines

of psychiatry, neurology, and

internal medicine. Instead of having students rotate through these specialties

via four-week consecutive blocks, students rotated in each discipline for

two-week intervals in a non-sequential manner and revisited each discipline at

defined intervals over the course of a four month period as noted in Table 1. The

clerkship settings between students completing the LSI curriculum and the traditional pathway

did not differ in terms of student distribution and time commitment. In both

groups, approximately 70% of students were assigned to an inpatient service,

while 30% were assigned to a consultation liaison service. As ascertained by

duty hour reports completed by students, there were not appreciable differences

by either group in terms of time devoted to daily clinical responsibilities and

subsequently time available for studying. Students

in neither group reported duty hour concerns during their clinical assignment.

Students in both the LSI and

traditional experiences each completed two on-call experiences in psychiatry and neurology, which

consist of participation in patient care activities until 10:00 pm on the call

nights. There is no on-call experience during the internal medicine rotation

for students in either the LSI curriculum or the traditional pathway. In

addition, considerable attention was focused on having student seminars be

active, as opposed to passive learning, and enhanced to present patient care

information in a clinically relevant, instead of discipline-specific, manner.

Unlike prior curricula, content was delivered by multiple faculties with

differing specialties. For instance, an internist, neurologist, and psychiatrist all

participate in the discussions of the approach to delirium. Emphasis was also

placed on enhancing clinical and procedural skills and modeling of positive

faculty physician behavior. The Ground School consisted of week-long intensive

course in procedural and clinical essentials of the three disciplines. This

review included data of third-year medical student clinical performance

evaluations in psychiatry and examination performance from approximately 75

medical students who participated in the clerkships described from October 2013-February

2014. In order to be a candidate for the pilot program, students had to be in

good academic standing, as defined by the College of Medicine. There were a

total of 15 students who volunteered to participate in the pilot program

described above. Sixty students enrolled in the traditional sequential block

rotations of psychiatry, neurology, and internal medicine during this same time

period served as the comparison group. The

study endpoints included comparison of National Board of Medical Examiners

(NBME) examination scores and comparison of clinical performance evaluations

for students in both the pilot and traditional psychiatry,

neurology, and internal medicine clerkship groups. The researchers utilized

t-test statistical analyses to determine if there were trends or statistically

significant findings between the comparison groups. Demographic data on the

study participants was not available. Students also completed multiple surveys

to assess their satisfaction with faculty and the clinical experience and its

various components; however, this data was not the focus of this research

project. There

were no significant differences between the pilot vs. control students in terms

of their academic performance measures in medical school prior to the study.

The average clinical performance evaluations scores

of students participating in the LSI Pilot were 84.7, whereas

those enrolled in the traditional pathway scored 80.3 (p=.072). Data from clinical performance evaluations of students

during neurology

and internal medicine clerkships was not available for the purposes of this

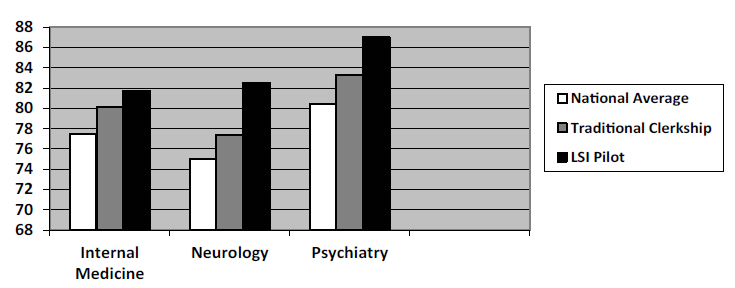

study. Figure 1 demonstrates that the NBME subject examination class averages

of students enrolled in the combined internal medicine, neurology, and psychiatry pilot

program were all relatively higher compared to students completing these

examinations and enrolled in the traditional block rotations during the same

time period. The data for both the clinical and examination performance did not

reach statistical significance (internal medicine p=.085, neurology p=.068, psychiatry p=.061). Measures of clinical performance, namely evaluations from

faculty, were noted to be slightly higher for pilot students compared to

students not enrolled in the pilot. In psychiatry ratings

specifically, students performed above average on clinical measures of medical

knowledge, communication skills, and diagnostic assessment and critical analysis

skills. Medical schools across the nation continuously look to improve the

educational outcomes and quality of the student experience; yet, there remains

a gap in understanding the meaning and significance of outcome measures in

novel curricula. In this experience, the LSI curriculum was specifically

targeted to enhance the critical thinking skills of students, drive faculty

-student interaction, and maximize the collaborative learning context of patient

care. The lack of statistically significant differences between study and

control groups suggests that the benefits, if any, of an integrated clerkship

may be negligible. However, the preliminary results of the pilot program offer

reason for educational leaders to be optimistic. In this study, the academic profile of the pilot students was not different

than the comparison students; yet, the pilot group posted examination scores

that were on average, higher. Similarly, the pilot program was considered a

success from the results of the students clinical performance in psychiatry, in spite

of the study limitation of small sample size of the groups. Like similar studies

exploring new curricular modalities, the rationale for this difference is not clear

and this pilot study has several limitations. Specifically, these results are difficult to interpret given the

study limitations of a small pilot group sample size, unequal numbers of students

in the pilot and comparison groups, selection bias of the curricular

assignments, and the inability to define the component of the LSI program that most readily influenced performance measures. The pilot program was noted to have considerable obstacles to

implementation, some predictable and others unforeseen. Perhaps the greatest

challenge was faculty buy-in to a program which structurally provided less

continuity of care than traditional longitudinal clerkships that generally occur

on an outpatient basis. The sequence of two-week rotation blocks not only posed

a tactical challenge for coordinators and clerkship directors alike, but both faculty

and students commented on the frequent interruptions to begin a new service

when they were just feeling comfortable with their current teams and patient

care responsibilities. Psychiatry

faculty, especially, were initially struggling with the concept that they would

have shorter durations of exposure to students, albeit equating to a proportionally

similar overall duration of psychiatry experience throughout the longer pilot program.

Some faculty expressed concern that shorter psychiatry rotations would allow

for less time for students to use feedback to identify and modify deficiencies

in clinical performance. However, faculty demonstrated improved buy-in as

students returned to services with reinvestment in learning psychiatry

following a hiatus for several weeks. One other limitation that could have

impacted the performance of pilot students was that they received first choice of

faculty preceptors, thus some selection bias may have favored the student-supervisor

pairings. Due to the small size of the LSI cohort, this study did not formally

examine the relationships, if any, between curriculum completed and interest in

future careers in psychiatry. Anecdotally, one student in the LSI group stated an interest in pursuing a psychiatry residency. The

authors are considering future studies to retrospectively determine if switching

to the integrated curriculum had a positive, negative, or neutral effect on

recruitment into the specialty. Further, additional studies of larger cohorts would

be directed at measuring intangible benefits recognized by longitudinal

integrated clerkships, such as practice habits in residency suggestive of

better clinical preparedness and pre- and post-assessments of social

determinants of illness and recovery between control and study groups. While the results of the pilot program represent a relatively small

sample of the medical student population, further information is anticipated to

be forthcoming to determine if the results are able to be generalized to the

entire third-year class. All students have subsequently been enrolled in the LSI Curriculum for the 2014-2015 academic schedule and will be

participating in this experience in years to come. Figure 1: NBME Score Performance of Traditional Clerkship vs. LSI Pilot Students The

results of this preliminary study support earlier lines of research

demonstrating promise in academic and clinical outcome measures with novel

curricula. Undertaking a massive curriculum revision has necessitated the investment

of considerable resources and collaboration across departments, with buy-in at

both the faculty and student level critical for the program to be successful. 1. Teherani A, Irby DM, Loeser H. Outcomes of different clerkship

models: longitudinal integrated, hybrid, and block (2013) Acad Med 88: 35-43. 2. Griswold T, Bullock C, Gaufberg E, Albanese M, Bonilla P, et

al. Psychiatry in the Harvard Medical School-Cambridge Integrated Clerkship: an

innovative, year-long program (2012) Acad Psychiatry 36: 380-387. 3. Hirsh D, Gaufberg E, Ogur B, Cohen P, Krupat E, et al.

Educational outcomes of the Harvard Medical School-Cambridge integrated

clerkship: a way forward for medical education (2012) Acad Med 87: 643-650. 4. Poncelet A, Bokser S, Calton B, Hauer KE, Kirsch H, et al.

Development of a longitudinal integrated clerkship at an academic medical

center (2011) Med Educ Online 16. 5. Greenhill J, Poncelet AN. Transformative learning through

longitudinal integrated clerkships (2013) Med Educ 47: 336-339. 6. Walters L, Greenhill J, Richards J, Ward H, Campbell N, et al.

Outcomes of longitudinal integrated clinical placements for students,

clinicians and society (2012) Med Educ 46: 1028-1041. 7. Reiter HI, Eva KW, Rosenfeld J, Norman GR. Multiple mini-interviews

predict clerkship and licensing examination performance (2007) Med Educ 41:

378-384. 8. Eva KW1, Reiter HI, Rosenfeld J, Trinh K, Wood TJ,

et al. Association between a medical school admission process using the

multiple miniinterview and national licensing examination scores (2012) JAMA

308: 2233-2240. Julie Niedermier, The Ohio State

University College of Medicine, 1670 Upham Hall, Columbus, OH 43210,

USA, E-mail: Julie.niedermier@osumc.edu Niedermier

J, Teater J, Kasick D and Jahdi M. A Comparison of Third-year Medical

Student Clinical and Examination Performances in a Traditional

Psychiatry Clerkship to a Novel Pilot, LSI Curriculum (2015) EPOA 102:

7-10 Curriculum innovation; Longitudinal integrated clerkship

A Comparison of Third-year Medical Student Clinical and Examination Performances in a Traditional Psychiatry Clerkship to a Novel Pilot, LSI Curriculum

Abstract

Method: The authors reviewed clinical evaluations and examination

performances of 15 students enrolled in a pilot curriculum to 60 students who

participated in the traditional curriculum. The nove Lead Serve Inspire (LSI)

curriculum consisted of a longitudinal integrated hybrid of internal medicine,

neurology, and psychiatry rotations and didactic instruction spanning nearly

four months.

Results: The National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) subject

examination class averages of students enrolled in the combined internal

medicine, neurology, and psychiatry pilot program were not significantly

different compared to students completing these examinations and enrolled in

the traditional block rotations during the same time period. On clinical

performance measures in psychiatry, students performed above average on

clinical measures of medical knowledge, communication skills, and diagnostic

assessment and critical analysis skills. Full-Text

Introduction

Methods

Results

Discussion

Implications for Educators

References

Corresponding author:

Citation:

Keywords