Research Article :

The main objective of

this study was to assess the challenges and prospects of community-based

ecotourism in the Maichew cluster, a case of Ofla woreda. Community based

eco-tourism has become rapidly the most fundamental in-strument to meet

sustainable tourism and livelihood option demand across the world at large and

Developing Countries in particular. In order to achieve the objective of the

study, both primary and secondary data were generated by employing qualitative

(using case study, focus group discussion, in depth interview and on spot

observation) and quantitative (mainly using household survey and visitor survey

questionnaires) methods. Purposive and simple random sampling techniques were

used to select 3 CBET sites and 90 sample households respectively. The

quantitative data was analyzed using fre-quency, percentage and mean when

appropriate while qualitative data was used to triangulate and substantiate the

study. The research investigated the challenges for developing CBET in the

study area. On the other hand, the study also identified several potentials of

CBET in the study area. In addition, the issues for empowering community based

eco-tourism in terms of economical, social, political any psychological

empowerment was identified. The result of the study reveals that several

challenges for empowering community based tourism in the study area, Low level

of knowledge, interest and perception of local community towards CBET; the resource

ownership questions like land; capacity problems of the MCs and local level

government office staff; lack of legal registration of CTEs; conflicting policies

and legislations; communities expectation for immediate financial benefits;

quality and standard of products and services; lack of cooperation among

stakeholders; emerging challenges on marketing and booking; etc. However,

several opportunities like strategic location of the sites, change of local

attitude toward CBET, hospitality of local community, the potential tourism

resources of the area, successful efforts on marketing and promotion, etc. are

identified as a positive factor for CBETE. The issues of CE process is in its

infant stage despite local communities showed high interest levels to involve

in identifying problems, management, decision-making, problem solving,

equitable benefit sharing and tourism operation. Thus, economical, social,

political and psychological empowerments of community are not well practiced.

To conclude, even if community empowerment can play central role to achieve

sustainable tourism development and livelihood option, the process is very

limited and in its infant stage in terms of economical, social, political and

psychological empowerments. Over the last half century, the growth and development of tourism as both

a social and economic activity has been remarkable. International tourism is

notable in particular for its rapid and sustained growth in both volume and

value since 1950. Technological developments, particularly in air travel;

increases in personal wealth; such as holidays with pay, all of which have

enabled more people to travel internationally and more frequently or, more

succinctly, contributed to greater international mobility. In 1950, total

worldwide international tourist arrivals amounted to just over 25 million. By

the start of the new millennium, that figure had risen to more than 687 million

and since then international tourism has continued its inexorable growth

(Sharpley, 2009). In 2009, over 880 million international arrivals were

recorded (UNWTO, 2010). The substantial growth of the tourism activity clearly marks tourism as

one of the most remarkable economic and social phenomena of the past century.

For many developing countries tourism is one of the main sources for foreign

exchange income and the number one export category, creating much needed

employment and opportunities for development. Globally, as an export category,

tourism ranks fourth after fuels, chemicals and automotive products. The

contribution of tourism to economic activity worldwide is estimated at 5%. Its

contribution to employment tends to be relatively higher and is estimated in

the order 6-7% of the overall number of jobs worldwide (UNWTO, 2010). According

to UNWTO tourism highlights of 2010, the overall export income generated by

inbound tourism including passengers transport, exceeded US$ 1 trillion in

2009, or close to US$ 3 billion a day. Tourism exports account for as much as

30% of the worlds exports of commercial services and 6% of overall exports of

goods and services (UNWTO, 2010). Apart from a vehicle for economic

development, tourism is also increasingly becoming at important sector for

instigating cultural and environmental conservation in many countries. In this regard, Ethiopia is among the worlds least developed countries

and some people living below a poverty line equivalent to 45 US cents per day

out of a population of 90 million; and up to 13 million people at risk of

starvation. Over 80% of its population is lives in rural areas, with agriculturally-based

livelihoods and extremely low levels of off farm income (Mann, 2012). However, as one mechanism of tackling poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa, the

potential of tourism was mentioned in World Bank report. Tourism is one of the

major economic sectors of Ethiopia and the government has labeled tourism as a

priority sector, in part as a tool for poverty alleviation (Mann, 2006). It

would be no exaggeration to say that Ethiopia has a cornucopia of attractions

of many types ranging from landscape scenery, wildlife, culture, history, and

archeology sites that set it apart from its neighbors. Its natural and cultural

assets are unique and potentially very productive for CBET. The challenge is thus to formulate tourism development strategies which

specifically harness this benefits into the local community. The effectiveness

of tourism in the future will ultimately depend on what form of tourism has to

be developed and who will benefit, as well as where, when and how it can be

appropriately implemented. Different types of tourism will assume different

forms and functions, and how they are developed and managed will also influence

the degree to which they can contribute to development. In this regard, CBET

has emerged as one of the most promising methods of integrating natural

resource conservation, local income generation and cultural conservation in the

developing world (Miller, 2004). World ecotourism summit held in Canada by the

year 2002 acknowledged the significant and complex social, economic and environmental

implications of tourism and the role of ecotourism in ensuring sustainability

of the overall tourism by increasing economic benefits for the host community

(TIES, 2000). Although CBET has long been taken as a sustainable development strategy

for developing countries like Ethiopia, no such community-owned and managed

products have come to the fore in a lasting and meaningful way. This is not to

say of course, that there are no attempts to develop CBET destinations rather

community participation in tourism has been exceptionally poor and genuine CBET

is rare. However, CBET will only bring benefits to conservation and communities

if good quality, viable ecotourism products, which reflect market demand, are

created and actively promoted. The tourism policy of Ethiopia which is endorsed

in 2009 highlights some specific provisions for active participation of local

people in tourism. Yet, despite this policys call for community involvement in

tourism, there is still no formal mechanism for community participation. CBET developments are most of the times aimed to realize the betterment

of livelihoods for the people suffering from different problems caused by food

shortage, population pressure, marginality and decline in productivity of land.

Denman state that in CBET communities assume substantial control over, and

involvement in; its development and management, and a major proportion of the

benefits remain within the community. In line with this it is increasing the

strategy to help address economic and social problems in local communities, and

as an appropriate and effective tool of environmental conservation (Denman,

2001). The full and effective participation of local communities in the planning

and management of ecotourism has become increasingly debatable issue. At best,

ecotourism projects tend to aim for the involvement of local people, and at

worst, ecotourism projects can ignore the issue of local participation

completely. Such projects frequently fail after a relatively short period of

time (Garrod, 2003). The participatory planning approach implies recognition of

the need not only to ensure that local stakeholders become the beneficiaries of

tourism development but also to integrate them fully into the relevant planning

and management processes. This is particularly important in the context of

ecotourism, where genuine sustainability can only truly be aspired to with the

effective participation of all of the stakeholders involved (Garrod, 2003). Even though the degree of benefit accruing to the local economy is

unknown; in Ethiopia there are already small scale benefits to the community in

general and the poor in particular with considerable difference between regions

and the destinations it is unanimously known that the major proportion of the benefits

go to the tour operators that are mainly based in the capital city. Next to the

tour operators, the local tour guides benefit significantly at local levels.

The elites or influential people are also among the most benefited (Kubsa,

2007). This situation leads to debate on tourism development in Ethiopia.

Monopoly of the sector by small groups of private investors means that adverse

impact on the environment and local communities have received insufficient

attention (Connell and Rugendyke, 2008). However, the more local residents gain

from tourism, the more they will be motivated to protect the areas natural and

cultural heritage and support sustainable tourism activities (Liu, 2003). Moreover, many challenges still lie ahead in promoting CBET at start up

and operational phase on the demand and supply side of tourism management. The

challenges facing the tourism industry are complex and numerous. Since tourism

sector is a growing sector, most of the local communities are not aware about

the economic, social, cultural and environmental significance and impacts of

tourism sector and some of the members of local community will not support the

community based ecotourism projects. In addition, studies indicate that many

community based projects have failed, usually because of lack of financial

viability (Mitchell and Muckosy, 2008). As a result, it is still rare to find

examples where projects are not initiated, planned or managed by forces outside

the community (Belsky, 1999; cited by Miller, 2004). On the other hand, when the NGOs fully implement the project and hands

over management to the community, the project can easily fail because there has

not been either initial or sustained support on the part of the community.

Despite these obstacles, developing ecotourism is not unreachable idea, but a

project that can be realized if the community is embraced and supported by

efficient communication and cooperation between the various stakeholders so as

to improve the livelihood of rural communities. CBET initiatives all faced some

difficulties and constraints in their due course of development and operation

to achieve sustainable development, but their experiences provide lesson for

others. As a driving force, approaches followed to develop and integrate CBET as

a livelihood diversification option, the extent and type of challenges and

opportunities faced during the entire phases of CBET development require

thorough study. Some researchers have done studies on community based ecotourism in

different parts of Ethiopia. These researches have mainly focused on surveying

potentials for community based ecotourism development and value of ecotourism

for wildlife conservation and economic development (Micheal, 2008; Cherinet,

2008; Sewbesew, 2010). However, study on the level community empowerment tasks

carried out to develop CBET, challenges faced and opportunities realized are

remain untouched. In an attempt to bridge these gaps, the study focus on

empowering CBET by taking Maichew

cluster, Ofla woreda as a case study. The reason why this site is selected as an area of study, Maichew cluster, Ofla woreda has a

tremendous potential of cultural and natural heritages but from these resources

the local community didnt benefit and there is no community based eco-tourism

empowerment project which are mainly support the local community livelihood.

So, the majority of the households in the area are categorized as chronically

food insecure and there are no CBETE practices to improve the livelihood of the

local communities as a whole. Besides, no CBET study has been done so far on

issues of empowering CBET. With this assumption this research initiated to

study in Ofla woreda. Description of The Study

Area Ofla is one of the five rural woredas in South Zone

of Tigray region that has 20 tabias/ 18 rural tabias & 2

urban tabias. Its geographical location is in between 39°31 E longitude,

12°31 N latitude. It is bordered with Endamohoni woreda in the North, Raya

Azebo woreda in the North East, Alamata woreda in the South East and Amhara

regional state in the West. The woreda capital is called Korem & is located

172 km from regional capital and 663 km from Addis Ababa. Its area is

approximately 1086.55 sqkm or 133500 ha. The wereda comprises 25% plain land, 20% gentle

slopping, 15% undulating and rugged terrain and 40% steep mountains. It has a

total area of 133,500 hectares. Out of this 25275 (18.9%) hectares are

cultivated land, 24340 (18.2%) hectares grazing land, 44635 (33.4%) hectares

forest and bush land, 1457 (1.1%) hectares lake area and the rest 37796 (28.3%)

are waste lands from all tabias of the study area Whereas it is focused on only

three major eco-tourism tabias Ofla woreda, they are Hashenge, Menkere and

Mifsas Bahri, these three tabias are bounded by Lake Ashenge. The study tabias

are characterized by undulating surface having flat lands and mountainous

chain. The mountains that surround the flat grazing land, cultivated land and

lake area are characterized by gentle to very steep slopes with average

elevation ranging from 2440 to 3600 m above sea level (Habtom 2010). There are three agro-climatic Zones in the Wereda

with greater domination of the high land or “dega type. The dega zone comprises

about 42% of the Wereda followed by “woina dega” and “kola” 29% each. Rainfall

has two seasonal occurrences in a year. During the kremt season, rainy season, it ranges from 450-800mm and it reaches

between 180-250mm during Belg season. The highest rainfall under normal

condition usually recorded during the July month. The Wereda has moderate type

of temperature that usually extends between 6o c to 32o

c. Moreover, about 33.4% area of Ofla Wereda is covered by natural vegetation

and is among the few areas to have such large tree cover in the southern zone

of Tigray (OWWSSP, 2004/5). The livelihood of the region depends on subsistence

farming. Livestock husbandry and crop production play a major role in the

subsistence farming. The dominant farming system is a highland mixed farming

system. The most serious problem for the agricultural production is the

shortage of land holding, ranging between 0 and 0.75 ha per household. As a

result, farmers are informally owning and cultivating the land up to the lake

boundary and some part of the upper sloppy areas which causes much sediment

accumulation in the lake. Data

Instruments: To undertake this study, both primary and secondary

data were generated by employing both qualitative (using focused group

discussion, in depth interview and on spot observation) and quantitative

(mainly using household survey and visitors survey questionnaires). The subjects of the study are both male and female

from the host community of the selected CBET sites. The total sample is 90

households using the following sample size determination formula adapted from

Israel (1992).

The selected study sites have a total of 557

households; out of which 291, 80 and 186 households live in Ashenge, Menkere,

and Mifsas Bahri respectively. By using the above formula, the sample size

becomes 84.779 households. Accordingly the sample size made 90 HHs. The

distributions of sample size across the CBET sites were proportionally selected

based on their size of households. Accordingly 47, 13 and 30 sample households

were taken from Ashenge, Menkere, and Mifsas Bahri CBET sites respectively. As

far as sampling technique is concerned first, the study area and the study

sites are selected with non-probability sampling technique purposively even

though the sample households were identified using probability sampling

technique.

Questionnaires consists of both open and closed

ended questions, were used to obtain information from the selected samples of

90 households from three major CBET sites of Ofla woreda. Questionnaire consisting of both open and closed ended

questions were prepared in English to generate data from 21 tourists who

visited three CBET sites of the study area during the filed research period. In

addition to questionnaire, focus group discussion (FGD) is the most important

data collection tool to generate the qualitative information. In general, The

FGDs were conducted in the selected three study sites.

Meaning each CBET sites was one FGD. For these, a

checklist of issues was prepared and the participants of FGDs was composed of

Management Committees, community representatives, religious leaders, local tour

guides, local service providers, guards and other stakeholders. The researcher

had a role of facilitating the discussion and took note on important

reflections on pre- arranged thematic issues on community role in tourism

activities and community based eco-tourism empowerment. For the purpose of this

study semi-structured face to face key informant interviews were conducted with

five different groups which account for a total of ten key informants. They

were taken as key informants based on their knowledge and responsibility in

relation to community based ecotourism in the study area. For each interviewee

group, independent checklists were prepared. Finally, to supplement the

information using different instruments, on spot observation were by the

researcher. On-spot observation was the other component of data collection

process. It includes observation of the major tourism resources, infrastructure

patterns, tourism activities, tourist services and facilities; natural

resources particularly forest and lake management and its coverage in the study

area, social interaction of tourists with host communities, manmade (cultural)

attractions like churches and monasteries, archaeological sites and the

conservation practices, and accommodation conditions of visitors. Thus, the

researchers opinions on his visit of the study area were assets to the analysis

of data gathered form other tools. In an effort to make this research more

valid, creditable and applicable secondary sources which are important to the

study were review. For this purpose, both published and unpublished sources

were investigated thoroughly especially books, web pages, policy directives,

reports, project papers, magazines, newspapers, annual action plans and so on

were critically reviewed. The secondary data (documents, reports, action plans,

etc.) were collected from the study area (Ofla

woreda) and Tigray Culture and

Tourism offices as well as other concerned bodies.

Data Analysis and Interpretation: The information gathered from different sources,

were compiled to manage in the most appropriate way. During the completion of

the data collection, the household information and visitors survey information

were coded and entered into Statistical Package analysis. The results of

analysis were interpreted and analyzed using descriptive statistics (frequency,

ratio, mean and standard deviation). Qualitative data obtained using FGDs, key

informant interviews and observations were analyzed in word narrative way.

Pictures, Tables and a simple bar charts were used for present the results of the

study.

This

section focuses on the analysis of the basic characteristics of the sample

households. This include the principal demographic variables such as gender,

age, level of education, marital status, family size and source of income and

status of agriculture to support the livelihood of the 90 sample households

collected from the three CBET sites selected from the study area. In order to

identify variations the data are summarized from CBET sites.

Gender, Age and Educational

Status of Sample Households: The survey result of this study for the characteristics of gender, age

and educational background of heads of household is well presented below. The

overall sample population is 90 (16.2 percent of total household in the sites)

of which 75.6 % and 24.4 % respectively constitutes males and females. The

distribution of households by the CBET sites accounts 52.22%, 14.44% and 33.33

% for Ashenge, Menkere and Mifsas Bahri respectively. With

respect to age structure of sample households, the maximum and minimum age of

the sample households are 85 and 21 years respectively. The majority of heads

of households (32.2%) belong to the age category ranging between 41 to 50

years. The sample households between 15 to 30 years old and above 60 years old

account for about 15.6% each. The rest of the sample population is 18.9%

and17.8% were those aged between 31 to 40 years and 51 to 61 years

respectively. While, the mean age of the sample household heads is 46.69 years,

the mean age of sample household heads of Ashenge, Menkere and Mifsas Bahri

CBET sites is 46.83, 44.81 and 51 years respectively. The data reveal that, on

the average, the households are in the adulthood age category, which could have

positive implication in terms of labor resource for tourism sector. An

educated household in the tourism sites is able to understand technical and

scientific concepts. Thereby actively participate in tourism development tasks,

perform tourism activities up to the standard and manage tourism products

properly. All these elements excel the performance of the community tourism

destinations and result in a positive return of tourism. According

to survey result, in terms of educational background of the sample respondents,

illiteracy rate is found to be higher. Almost 61.1% of the sample household

heads are reported to be illiterate without having formal education. Likewise,

16.7 % of the sample population was reported that they can read and write. Most

of these households have got limited access to basic education, which is

claimed to be acquired through some informal and traditional religious

education as well as adult literacy campaigns. On the other hand, about 16.7%

and 2.2% of the sample households are found between grade 1-4 and 5-8

respectively. Similarly, about 1.1% of the sample population attended a high

school and preparatory level (between 9 to 10 and 11 to 12 grades). Of the

total sample size, only a very few (2.2%) of the respondents had acquired one

year certificate from teachers training college. An

effort has been made to see the educational status of the sample household

heads in the respective CBET sites. Accordingly, 63.8%, 69.2% and 53.3% of the

sample households in Ashenge, Menkere and Mifsas Bahri are illiterate

respectively while 19.1%, 7.7% and 16.7% of sample households of Ashenge,

Menkere and Mifsas Bahri CBET sites can read and write but they dont have any

formal education. On the merit of this survey, one could say that in the study

area included in the sample, the household heads that have no education and low

level of education dominate the entire population. Generally, as shown in the

above table, 77.8% of household heads were not educated. This in turn, could

have its own implication in relation to community based ecotourism development. To view Table 1, click below According

to the interview with the cooks of the CTHEs and CTFEs, there is significant

association between marital status of the females and community tourism where

majority of the cooks of CTHEs are single and divorced. With respect to family

size per household, as it is depicted in table 2 below about 54.4% of the

sample households contain between 4 to 6 family members. The mean family size

of the sample households was 5.57 persons. The mean household size of Ashenge,

Menkere and Mifsas Bahri CBET site households was 6.02, 5.15 and 5.03 persons

with standard deviation of 2.12, 0.86 and 0.57 persons respectively. The

family size data reveal that the great majority of the households (83.3% of the

total sample population) are found to have four or more household family

members of families under households. This in turn implies that as the family

size increases, the dependency ratio of the households will be high. As a

result, since current benefit sharing strategy of CTHEs from tourism is on

merit of the household heads membership, large family size results important

differences among the households income negatively. To view Table 2, click below To view Table 4, click below According to the survey result, the different

ecotourism potentials attractions of the Ofla woreda and its surrounding areas.

During the household survey and field observation study area and its

surrounding areas comprise impressive attractions of natural and cultural

settings that are the prominent sources of ecotourism potentials development.

The natural resources of the area are Forests, Hashenge Lake, Birds, Mammals,

Weather condition, Hot springs at the valley of the forest, Holla

waterfall and Mountain/landscape scenery (Hugumburda in menkere and Mifsas

Bahri tabias, Tsibet highest mountains in Tigray region, Ambalagie and

Alamata mountains are important for mountain trekking/climbing) while the

cultural attractions are dressing styles (such as bufie), Tigile (in Amharic),

cultural dances, local handicrafts, folklore/indigenous knowledge Mifsas Bahri

archaeological site and religious sites (mosques and churches such as Mehaber

Bekurie and St.maryy Adota are important religious sites for tourism

development). This shows that, Ofla woreda and its environs have prominent

ecotourism potentials that will be important for future ecotourism development.

According to (Keivan et al. 2006),

today, many countries are encouraged to allocate a sizeable amount of

investment to the tourism and ecotourism sector since tourism industry

generates high income and conserve the environment sustainably. In general, as it could be observed from finding, the

main natural ecotourism potential attractions are the lake, forests, mountains,

birds and as well as the wild mammals, which can attract tourists and may

contribute to the conservation of natural resources and improves the

livelihoods of the local community if they are developed. Holden (2003) also

acknowledged that the ecotourism resource in protected areas could generate

more revenues, which could benefit the local people and contribute to

conservation of protected areas.

The Ofla Woreda and its surrounding areas have

tremendous potential for community based ecotourism empowerment that can

provide the much needed employment and economic growth in the area. Due to

different factors and challenges the ecotourism activities were not carried.

The communities forwarded different point of view on how ecotourism may not

developed in the study area and its surrounding areas. The data or information

which was gathered from the survey (questioner) and focus group discussion is

almost similar. Therefore, According to the respondents, the remarkable

problems that hinder the ecotourism development can be generalized in different

factors and challenges. For details each factor is given below; In this part of data analysis

two fold of challenges: challenges faced on development of CBET and after CBET

are presented by triangulating both quantitative and qualitative data. Knowledge and Interest of

Community toward CBET: Knowledge and interest can affect the degree of community participation and

ownership in tourism development. Given that community participation ownership

is a crucial element of CBET, low level of knowledge and lack of community

interest in CBET development will affect the overall sustainability. Some

researchers proved that lack of tourism knowledge is critical barrier that

limits the ability of locals to participate in tourism development which

contributes to a lack of local tourism leadership and domination of external

agents. Limited awareness of CBET can contribute to false expectations about

the benefits of tourism lack of preparedness for the changes associated with

tourism. Lack

of knowledge of meaning and values of CBET is a significant factor that could

affect the participation of communities and efficiency of the tourism sector.

Accordingly as it is depicted on table 8 below, to know the extent of

understanding that the communities have about CBET; sampled households were

asked whether they know what CBET does mean. Majority (96.7%) of the sample

households were not familiar with the term CBET while the remaining (3.3%) of

the sample households knows the term CBET. Maichew tourism and culture office

coordinator and other focus group discussants express that lack o of the CBET

project is the main reason for the local communities were not aware about

tourism. But, currently some CBET activities on the way to conduct by the

different organizations like Tigray culture and Tourism, Mekelle University to

the community come to know about tourism and community based ecotourism. An

effort is also made to assess the knowledge of focus group discussants and

CTHEs staff. In the FGDs some members of the community are not proudly speak

that they know what CBET means. But

some local people defined CBET in their own understanding. Generally, focus

group discussants not similar feelings about CBET being, “a kind of tourism

runs by communities with sound participation of the community to achieve

the economic needs of the area.” In this definition the role of CBET in

environmental and cultural protection and conservation is forgotten. Informal

discussions with local community also reflect the same thing: focused on

economic advantages only. This could create extra challenge on the task of

ensuring environmental and socio-cultural sustainability. Corresponding

to this, the sample households were asked to illustrate the source of their

knowledge about CBET. Sampled respondents describe that there is no awareness

creation activities and projects as well as trainings made by the concerned

bodies. To better understand how the community feels and understands community

based ecotourism, sample households were also asked whether they know that any

community based ecotourism activities are not going on their kebeles. The

survey result depicted above in table 8 reveals that the entire sample

households (100%) were knew that their kebeles are not practicing CBET. In

line with this, MCs who are in charge of tourism management and participated in

the interview explain the current knowledge basis from perspective of benefit

that they are not sufficiently start. They stated, all seasons of

misunderstanding about tourism and resistances are still not over by the

community. In addition they said that, after many consultations and training it

is an opportunity to create awareness about CBET. In a

nutshell, the overall results of this study identify knowledge as a critical

barrier of CBET in two reasons. Firstly, lack of knowledge about the value of

CBET makes things too complicated i.e. resistance were the response of local

community. Secondly, lack of knowledge among the community about technical

tourism works like bookkeeping, marketing and booking, food preparation,

foreign language, etc. are the critical knowledge related barriers that CBET

have been facing in the study area. Of course, these issues are challenging

even among the literate communities. Here, it is better to underline that lack

of educated persons do not only limit the benefit of single households, but

also the benefits of the whole community. Thus, effective capacity building and

human resource development plan should be mandatory. Attitude and Feeling of

Community towards CBET: The attitude and feelings of communities toward community based

ecotourism activities is a fundamental challenge that many of the projects had

faced. The knowledge of community has direct effect over attitude. The attitude

of community toward CBET should be compared to the interest and thinking of the

community in other development projects and economies like agriculture. It is

likely that community members are much more interested in projects that they

can relate to than to a community based eco-tourism empowerment project or

means of livelihood (in this case agriculture to CBET), which is for most

community members something that they are not familiar with. This could be much

more complicated in projects where the initiative comes from external parties

like NGOs. If

the community is not interested in CBT development, the development of CBT will

fail, given that community participation is a crucial element of CBT. Therefore

it is important to investigate the communitys interest in CBT development first

and foremost. Thus, sample households were asked the question, do you think

that you will fulfill your livelihood without farming? As it is depicted in

table 9 below and 54.4% of sample households have negative feelings about the

new means of household while 45.6% of sample households express their interest

for other livelihood options. According

to this, sampled households were asked to express their feelings when the

project will be implemented in their kebeles. The summary of households

responses reflects that most of the sample households not interested about the

new alternative livelihood option (CBET). According to the result of FGDs

initially, the innermost looking toward the CBET was associated with the

intention to transferring local residents from their owned agricultural land to

other place.

Ofla

woreda tourism experts, reflecting their personal experience, noted that since

community-based ecotourism is a new concept for villagers, it has been

difficult to convince villagers to adapt to the innovative approaches and

procedures about CBET. This has been very much complicated in the first

CBET site,Ashenge. The people dont recognize the opportunities that

tourism could offer them. Awareness creation campaigns involving information

about CBET andits relationship with economic value and nature

conservation were not held in each kebeles by the stakeholders. Thus, a

strategy toget the consent of some communities still not developed. At

this level those who get not convincedwith the idea of CBET do the same

for the whole community. Eventually, without anyconsultation, training

and explanation made by several community members, the community neveragreed

about the CBET development. Lack of coordination: The

tourism industry is multi disciplines (multi-sectors) which incorporate a range

of stakeholders, including governments, the private sector, non-governmental

organizations (NGOs), local communities, Religious leaders, and tourists. The

importance of community based ecotourism/ nature-based tourism is not lost on

national governments. They are fully aware to all institutions that it can

bring numerous socio-economic benefits to a country or locality, by generating

foreign exchange, creating local employment and raising environmental

awareness. As information obtained from the regional tourism office, tourism is

not at all a task of to be left for a single institution. Therefore, tourism

activity undertaking through the coordination of different institutions to

perform inter related activity. As the information obtained from the group

discussion, many participants agreed that there is no coordination between the

different sectors to develop ecotourism in the locality. While some

participants disagreed about this issues and the few participants does not

expressed about the cooperation of the different sectors. Lack of political will and capacity related problem of

Government offices: The

attention given to the sector by government is another critical challenge for

the development of CBET. While CBET is an important means of livelihood

diversification in developing countries like Ethiopia, the emphasis given to

tourism sector in general and CBET specifically is little. The institutional

structure in culture and tourism offices does not consider CBET. An important

indicator for this is the absence of any post to give guidance at federal,

regional and woreda level culture and tourism offices. Lack of possible guiding

principles and support on development of CBET product is identified as a

barrier too. Similarly,

the number of staff and their qualification is a big challenge for CBET

development work of the study area. At woreda level, culture and tourism

offices have only three staff where the manager is possibly working on the

political issues while the rest two employees are responsible for a collection

of works found in the office. Until, the time of this survey no experts of

Tigray Region Culture and Tourism Bureau and Ministry of Culture and Tourism

provide technical support for the CTEs. Besides, limitation of capacity on the

woreda level government offices is mentioned as a challenge by informants.

Culture and tourism related institutions should give due attention to CBET as

it is very decisive to achieve sustainable development. In this regard, the regional

and federal governments are expected to prepare a guide to CBET development and

a specialized marketing strategy which includes CBET as a core product in the

country.

Lack of Marketing and

promotional activities: The marketing and promotion activities done to promote the study area to

the potential customers are worth important as it is mentioned in the product

development part. The researcher identifies two options of marketing tourism

product of the study area: either the CTEs themselves or outsourcing the

marketing. However, capacity limitation of the community to perform the

marketing task is a critical challenge. In addition, limitation in terms of

lack of legal registration is limiting the CTEs action to outsource the

marketing task to somebody else through memorandum of understanding agreement

or contract. To these effects, now a day the marketing and booking become an

emerging challenge to the study area tourism activity. This is further

complicated with weak government intervention and attention.

As

the information obtained from the regional tourism office experts, most of the

countries tourism resources were almost unknown internationally and even by the

residents themselves, even those who have information about the countrys

tourism resource, the bad image that the country has retarded them not to come.

At the present time the Ministry of

Culture and Tourism, is responsible for developing and promoting the

tourism products of Ethiopia both inside the country and internationally.

However, the promotion still untouched on the natural attractions of the Tigray

region specifically in Ofla woreda. Therefore, the lacks of promotional and

marketing efforts have an influence in the tourism development. In addition,

during focus group discussion most of the participants agreed that lack of

promotional works to the natural resources of the study area can hinder the

community based eco-tourism development of the area. On

the other hand, CTGE have an interest to shoulder the marketing and booking

tasks carried out by the CTTSU. Now they are doing the marketing and booking

tasks by employing one booking and marketing officer at Mekele and took 20% of

the payment as their income for the marketing and booking they carried out.

However, they perform informally without agreement with CTTSU.

To

conclude, lack of agreement and cooperation against these challenges becomes a

critical barrier of marketing and promotion. Hence, for the time being the

regional culture and tourism and respective government offices should take the

leading role to discuss with relevant stakeholders on how and who should

managing the marketing and booking functions effectively so that income of

communities from the tourism business will not be in danger. This may involve

critical assessment of various options available, for instance, building the

existing internal capacity, empowering and legalizing the private enterprises,

forging partnership with private tour operators, and the like. In this

instance, respective government bodies should exercise their role to settle

this kind of issues.

Security Related Concerns: Criminal activity is probably

the greatest threat to the tourism industry. Occurrence of acts ofterrorism,

theft and other crises influence tourists flow to destinations. Tourists will

avoiddestinations perceived as unsafe. In Ofla woreda, significant

violent criminal activity directedagainst foreign tourists is rare. In

principle when the community is interested in tourism business,ensuring

security need of tourists becomes easy. The role of community in crime

protection ismore than everything as nothing is out of the sight of the

community. To guarantee security ofvisitors while they are in visiting

the forests and swimming in lake the luggage porters are taken instruction to supervise

theaction of community. The result of FGDs shows that initially in

relation to the negative feelingof the community towards tourism; there

were some security related issues directed to visitorslike throwing of

stones. The survey result depicted below in table 10 reveal that majority of

thesampled households (70%) report the absence of security problem

while the remaining sampledhouseholds (30%) alert that there is

security problem over the tourists. In the case of AshengeCTE the

question of tourist security is a big concern where more than 53% percent of

thesampled households were identified the problem of security over the

site. Three

major security related challenges are registered in the Ashenge. The MCs

identify bag snatchings and theft of Photo camera and a few night-time

robberies like theft of door and other materials on the grinding mill compound.

The issue of weak law enforcement and justice system is mentioned by the

majority of interviewees and all FGD participants held in Ashenge. The MCs of

Ashenge reflects their suffering on the justice system while they faced big

illegal matters like the aforementioned one. The justice organ there and police

organs are less successful to provide justice and take appropriate measure

against those who initiate and involve in illegal activities. Such

circumstances are reported eroding confidence of MCs in the ability of the

justice organ as a whole to bring justice. As a result, most of them preferred

to take their case to the local elders (Shimageles) than the Justice

system. To view Table 7, click below In

general, capacity related challenges are reasons to the overall attribute of

the CBET businesses. To ensure the success and sustainability of the project,

training need assessment has to be made for the community. Then technical

inputs should be provided to MC of community members, governments and service

providers. Inputs may include training on environmental issues, facilitation

skills, problem solving, report writing, micro-project/business design, project

implementation and management, implementation of relevant laws, and tourism

service techniques and management. The

last of these includes teaching CBET concepts, bookkeeping, accounting,

financial management, tour guiding, first aid, hygiene and sanitation, Basic

English conversation, computer skills, etc. Ensuring Quality and Standard

of CBET Products: A key

part of the businesses future sustainability lies with the ability of CTHEs and

CTGE to maintain quality in medium and long term. Quality does not necessarily

mean luxury, but attention to detail and understanding customer needs. There

are certain areas that cannot be compromised like, cleanliness and hygiene and

sufficient infrastructures being at the top of the list. Equally food should be

enjoyable to eat, beds should be comfortable and clean, and toilets need to be

clean. Careful monitoring of these elements will be the core part of any

quality control system. The quality of the product needs to be not just

maintained but improved. Limitation in capacity makes the service standards poor

gradually thereby dissatisfaction will be the feature of the product. Quality

and standard involves the character of staff of CBET business, communities

hospitality and food, transport, accommodation and other related service

quality and standard. As the information obtained

from the tourist survey that lack of infrastructure development is the main

problem for the development of eco- tourism. Generally infrastructure may

include road, hotels, air ports, water supply system, electric power,

communication system, Banking services and waste disposal facilities. The

respondents said that before they built up of the road from Addis to Mekelle

via Mehone, tourists were cross through the Ofla woreda. As a result, tourists

were observed ecotourism attraction of the area such as lakes and birds but now

since the main road were shift through Mehone tourists were not visited the

site. In addition as the information obtained from focus group discussion and

field observation there is no accessible road for observing different

ecotourism attractions in study area like the lake, the forest reserve. The

tourist survey result done to show what tourists feel about the overall

experience on the CBET site reflects that 71.4% and 28.6% of the respondents

rate their experience not excellent and average respectively. Even though, this

survey reveals negative looking of the guests since development come in the

world and some other competitive tourism products are open small improvements

need to be made on the top of maintaining the quality that was experienced by

customers at the start. Therefore, during field observation some quality

related challenges which seems simple but detrimental to the image of the area

are found. On Ashenge, Menkere and Mifsas Bahri CBET sites the accommodation

and infrastructural services are not functioning and there is a need to make

the services. Similarly, in both Ashenge and Menkere CBET sites, the

Accommodation services are not available. In

the discussion organized by Ofla woreda culture and tourism office held in the

Korem town participants mentioned declining of the cleanliness of the products

supplied in the private service providers. Some participants demonstrate the

lazy washing and absence of accommodation service. In addition, the tourism office

representative mentioned dropping off quality of the toilets as no one is

maintaining them properly and the restraints service have no well-organized and

qualified. Therefore, the tourists are complaining over it. The

other important area of CBET product qualities is the type and character of

transportation related with tour service. Transport carrying unit used to reach

the starting place of Hugumbrida forest and Ashenge Lake is not organized by,

local tour guides and/or the communities; but the surrounding town (Mekele and

Alamata) tour and travel agents have made arrangements on behalf of their

guests with some local vehicle operators. Donkeys are used for transporting

customers luggage. Horses are also used for transport purpose. The quality and

cleanliness of horses and donkeys should be kept in proper provision. For this

currently no suggestion and comment is collected from the visitors by the CTEs

and other bodies. Customer handling is also another critical element of

quality. Tourists were asked to rate the customer handling scale. Accordingly

71.4%, 19%, 4.8% of sample tourists rate the customer handling of the nearby

town tour and travel agents and service provider staffs are excellent, above

average and below average respectively while 4.8% of sample tourists have no

response

Equally

important, the service standard is dependent on the character of the staff

participating in service delivery. Staff of every tourism business organization

should give due attention to cleanliness and personal hygiene. They should

demonstrate the following grooming character; well-shaven or well-trimmed

facial hair, clean and well-presented hair, neat and tidy clothing, frequent

washing, appropriate use of deodorants or perfumes, fresh breath and either

neutral or pleasant body odors, clean and trimmed fingernails. The first of

staff are community tourism guides where guests come into contact. Quality of

guides is perhaps the single most important piece of infrastructure for the

tourists. The extent of knowledge and professionalism that guides have matters

the perceived performance of tourism too. To this end, tourists were asked to

rate the guiding service performance. Accordingly majority of the tourists

(67.7) rate the local guiding service as not excellent while 23.8% and 9.5%

percent of the sample tourists rate it as below average and average

respectively. Training in guiding technique and knowledge is vital. In line

with this, CTGE members were asked to explain the type of training they took to

be a tour guide. , the manager of CTGE, explained that by the time of CTGE

establishment criterias to select community tourism guide are not based on the

experience and academic back ground. Moreover, trainings were not planned to be

given for CTGE by government and other stakeholders. Underlining the strong language

skill of guides he stress on the need for further training on culture and

natural resources specific to the area. Similarly, the tourists comment on

improving of guides knowledge on the interpretation. Pertaining to guiding

facilities lack of tourist map showing route of the tourism sites are

identified as problem in the area. 1.

Asker

S, Carrard N and Paddon M. Effective Community Based Tourism: A Best Practice

Manual. Sus-tainable Tourism (2010) Cooperative Research Centre, Griffith

Uni-versity, Australia. 2.

Attama

N. Empowerment of Community-Based Tourism (2008) The Case Study of Pa Hin Ngam

National Park, Thailand. 3.

Berna

T. Developing Alternative Modes of Tourism in Turkey (2004) Turkey. 4.

Bradlow

K. Challenges and Opportunities of Partici-patory Planning Processes for

Natural Resource Management in Cambodia. In Emerging Trends, Challenges and

Innovations for CBNRM in Cambodia (2009) Phnom Penh: CBNRM Learning Institute

59-73. 5.

Blamey

RK. Principles of Ecotourism. In D.B. Weaver (Ed.) (2001) the Encyclopedia of

Ecotourism Wallingford: CABI 4-22. 6.

Bramwell

B and Lane B. Sustaining tourism: An evolving global approach (1993) J

Sustainable Tourism 1: 1-5. 7.

Bramwell

B and Sharman A. Approaches to Sus-tainable Tourism Planning and Community

Participation: The case of the Hope Valley. In D. Hall and G. Richards (Eds.)

(2000) Tourism and sustainable community development London 17-35. 8.

Connel

J and Rugendyke B (Ed). Tourism at Grass Root Level Villagers and Visitors in

Asia Pacific (2008) London and New York: Routledge. 9.

Denman

R. Guidelines for Community Based Eco-tourism Development (2001) Washington. 10.

Dodman

T and Taylor V. African Waterfowl Cen-sus 1995. (1995) International Waterfowl

Research Bureau, Slimbridge, UK. 11.

Duffy

R. A trip too far: ecotourism, politics, and ex-ploitation. (2002) Earthscan,

London. 12.

Duffy

R. Global Environmental Governance and the Politics of Ecotourism in Madagascar

(2006) J Ecotourism 5: 128-144. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724040608668451 13.

Epler

Wood M. Ecotourism: Principles, Practices and Policies for Sustainability. 1st

ed. Part-One (2002) UNEP, United Nations Publication 1-32. 14.

Fennell

D. Ecotourism: An Introduction (1999) Routledge, London. 15.

Fennell

D. Ecotourism: Where weve been; Where Were Going (2002) J Ecotourism 1: 1-6.

https://doi.org/10.1080/14724040208668108 16.

Fletcher

R. Ecotourism Discourse: Challenging the Stakeholders Theory (2009) J

Ecotourism 8: 269-285. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724040902767245 17.

Foucat

VA. Community Based Ecotourism Man-agement Moving Towards Sustainability, in

Ventanilla, Oaxaca, Mexico (2002) Ocean and Coastal Management 45: 511-529.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0964-5691(02)00083-2 18.

Funnell

DC and Bynoe PE. Ecotourism and In-stitutional Structures: The Case of North

Rupununi, Guy-ana (2007) J Ecotourism 6: 163-183. https://doi.org/10.2167/joe155.0 19.

Garrod

B. Local Participation in the Planning and Management of Ecotourism: A Revised

Model Approach (2003) J Ecotourism 2: 33-53. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724040308668132 Community Based Tourism; Eco-tourism; Community

EmpowermentChallenges and Prospects of Community Based Eco-Tourism in Maichew Cluster, a Case of Ofla Woreda

Abstract

Full-Text

Introduction

Main body

Figure 1: Map of the study area, (Source: Own development by ARCH GIS Classification).Methods and Data

Instruments

Flowchart 1: Design of the Research.Result and Discussion

General Characteristics of Sampled Households

Table 1: Gender, Age and Educational Status distribution of the Sample HHs. (Source: Field Survey).

Distribution of Marital Status and Family Size of

Sample Households: The

marital status of the households indicates that the large majority heads of

households (86.7%) are married. In contrast, the percentage of sample

households who have never been married was very low: 3.3%. From the survey

result, it was also possible to learn about 5.6% of the sample households have

been living in broken families due to divorce while the rest 4.4% of sample

households were widowed.

Table 2: Marital Status and Family Size of Sample HHs. (Source: Field Survey, 2016).

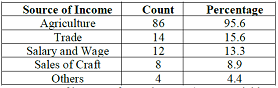

Source of Income and Status of Agriculture to Support

Livelihood of Sample HHs: CBET is taken as one tool of sustainable economic development. However,

local economic diversity is important to the sustainability of community based

ecotourism projects. A potential problem in the development of ecotourism for

rural communities is creating economic dependence on the trendy, fluctuating

industry of international tourism (McLaren, 1998, cited by Cusack and Dixon,

2006, p.162). The main livelihood of the study area is agriculture, with

mixture of subsistence crops and livestock (OWGAC, 2015). According to the

household survey, the major source of income for the sample households is

agriculture, where about 95.5% of the respondents get income from agriculture.

However, other sources of income like trade, and salary and wage account 15.5%

and 13.3% respectively while sales of craft and other non-farm sources account

8.9% and 4.4% respectively.

Table 3: Source of income of Sample HHs. (Source: Field Survey, 2016).

In an

attempt to see the status of agricultural productivity and output to support

the livelihood of the sample households as it has been indicated in table 4

below, sample HHs were asked about the status of agriculture to support their

livelihood. From the survey result it is possible to understand that most

households in the study area do not possess adequate food production. The

majority (61.1%) of the sample households (87.2% in Ashenge, 46.2% in Menkere

and 50% in Mifsas) replied that agriculture is not sufficient to support their

families livelihood while about 38.9% of the total sample households reported

that agriculture is sufficient enough for their livelihood. Those respondents

who indicated the insufficiency of agriculture were also further asked to

mention the reason for insufficiency. The most frequently mentioned causes

include low productivity of land, large family size, drought, pest infestation,

livestock disease, lack of sufficient agricultural facilities etc.

Table 4: Adequacy of agricultural income for the sample HHs. (Source: Field Survey, 2016).

Moreover,

the officials of Ofla Woreda noted that even though due efforts have been made

to increase agricultural production through agricultural inputs, extension

packages and introduction of agricultural technology; the production increment

has been rather limited showing a marginal increase. Thus, alternative

livelihood strategies like CBET in this area are very crucial to solve the food

insecurity. However, it needs to be highlighted that the effectiveness of

managed ecotourism is influenced by the poverty level of the people who live close to the tourist sites.Eco-Tourism Potentials

of the Ofla woreda

Challenges of CBET

Development

To view Table 5, click below

Table 5: Distribution of HHs by their Knowledge of CBET. (Source: Own Field Survey, 2016).

To view Table 6, click below

Table 6: Attitude towards other means of livelihood. (Source: Own Field Survey, 2016).

Table 7: Prevalence of security problem in CBET sites. (Source: Own Field Survey, 2016.

Capacity Problem of the MCs: Most of the challenges of

community based ecotourism emanates from problems of capacity building. The

community has not yet taken the full control over tourism in the study area.

Unless, the community becomes empowered to do decisions on the business aspect

the sustainability of the sector is under quotation. In community based

ecotourism enterprises where the product is based entirely on local community,

the standard and sustainability will depend on existing and potential local

capacity especially to the MCs and staff. The extent of human empowerment

achieved through capacity building is challenge of CBET success. However,

the communities are not empowered enough to take the full decision making power

from concerned bodies. Head of Zone Culture and Tourism Bureau put forward that

there is no sufficient capacity building program in the study area, this is

a big challenge for the empowerment and achievement of community based

eco-tourism. The probable challenge is creating the CTHEs more empowered

and enables them to do the memorandum of understanding agreement signed by the

CTHEs with the private sectors and other organs too. Currently many of

decisions on the CBET are made by Woreda tourism office. For example fishing

activities and pricing of the tour is a good example. As far as, it is

community based ecotourism the local community in the form of its CTHEs should

be the decision makers instead of government. In fact, support and moderate

participation of them is critical. Obviously, with current human resource

capacity of the CTHEs, administration of booking and marketing activities by

communities would be impossible. In addition, setting the price of tours and

the fishing activities is not done without analyzing the propensity to pay and

other destination prices. Thus, since the community has no skill on this

consultation is critical at this point. When the price of tours and fishing is

set for the third time by government, the communities have no says over it.

Lack of language skill is another capacity related problem seen in the study

area.

To view Table 8, click below

Table 8: Distribution of sample HHs by their feeling towards visitors. (Source: Own Field Survey, 2016).

To view Table 9, click below

Table 9: Issues of community empowerment in Ofla woreda. (Source: Own Field Survey, 2016).References

Keywords