Research Article :

Research indicates that at least 70% of

offenders reach criteria for personality disorder other than antisocial and,

due to the closure of mental health hospitals world-wide; there are an

increasing number of offenders with mental illness located in prisons. To fully

assess and reduce the risk an offender poses and to try to remediate that risk,

the underlying drives to offend must be understood and addressed. To do this an

offender must be genuinely engaged. It is suggested that this is in part due to

having poor attachment histories and no internal model of a healthy attachment.

This paper is written by a consultant clinical and forensic psychologist with a

long standing proven record of establishing and running services for and

working therapeutically with men with mental health issues with outstanding

results in risk reduction alongside and by an expert by experience who has

in-depth personal insights into the both the processes needed for effective

engagement and change. It describes useable strategies as to how to

successfully engage offenders and how to develop a healthy and reparative

therapeutic relationship. It describes the importance of a collaborative

clinical formulation to aid the development of a coherent narrative and of an

emotionally present and engaged therapist. The need to work on both victim and

offender issues to bring about real change and risk reduction is elucidated

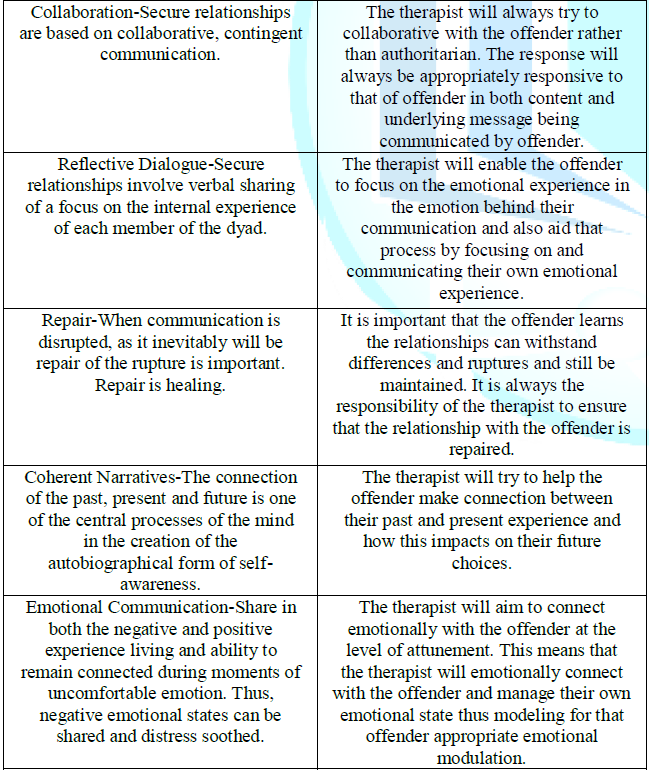

throughout. Failure to develop these connections leads to an inability to modulate emotional state, impaired ability to develop reciprocal social relationships and a disturbed sense of self [6]. Early experience does not cause later pathology in a linear way but plays an aetiological role in the complex, transactional nature of development [7]. For example, due to not having a secure base through attachment, they will not believe that they can rely on others; therefore they will not do so. Offenders are unlikely to have good access to their thoughts and feelings and will frequently act impulsively, or in what is perceived to be a planned manner, without any awareness of the underlying issues driving their behavior. They experience numerous negative automatic thoughts and have a lack awareness of their emotional states. They have learnt to block out emotions from conscious awareness and can state they feel nothing or tend to rely on one predominant emotional state, usually anger. They are rarely able to discern the underlying emotion or the triggers that led to the emotion and drive the subsequent behavior. Thus, as the harmful behaviors of offenders are primarily emotionally driven, a failure to access those emotions during treatment will leave the offender untreated and with a high likelihood of the continuation of that harmful behavior. The way individuals learn to identify and regulate their emotions and understand the experiences that trigger those emotions is through a secure attachment relationship [8]. Secure relationships are also known to promote socially adaptive and morally responsible behaviors through the impact of interpersonal relationships on the brains neural structures [9,10]. Adverse experiences in a childs early life negatively shape the development of the complex brain circuitry, thus impact negatively on the ability to develop healthy social and moral behaviors. Research now shows that contrary to previous views the brain is plastic and able to develop throughout the lifespan [11]. Thus, the aim of the therapy being proposed in this paper is that the individual therapeutic relationship needs to mirror a secure attachment relationship. That secure attachment relationship has been shown to actually change brain structure [12]. There are certain strategies that are needed to facilitate such a relationship to develop (Table 1). Table 1: Strategies needed to form an attachment relationship. By 12 years of age he owned a new BMW and by the age of 14 he was a father. The only person trusted was himself and he always had to be the one in control. He engaged in various criminal activities threatened, and engaged in, extreme violence, to protect self from any potential abuse by others. In relationships, slightest chance of abandonment would leave the person first to protect him-self. In prison, he was highly refractory. He was referred to a therapeutic unit in a high secure prison; he was diagnosed with antisocial personality disorder and bipolar disorder. He writes: At the start of therapy, I began to work with a psychologist. I initially thought she was a man-hater who was on a crusade to crush all men but in the space of months, I realized she was actually genuinely caring and not trying to manipulate me. Although I did not consciously realize it, I had already begun to emotionally trust her. Cognitively, however I didn’t trust her for at least the first year of therapy. This was played out in the fact that I would not look directly at her for that first year. My relationship with her changed when I began to realize that my therapist was connecting with me on an emotional level. She was able to pick up the emotion in my responses and feed that back to me; even changes in my tone of voice, or the way I looked or how I sat. As she became emotionally attuned with me and my experience and was able to hold my emotions, I began to be able to feel those emotions. Through this relationship, I began to be able to connect to my experiences as a child and most importantly, to connect to, and have empathy for, the part of me that was hurt as a child that I had repressed for many, many years. The relationship my therapist developed with me enabled me to feel safe enough to connect to my sadness and fear as there was someone who was genuinely caring and protective of my experiences as a child. I learnt that it was not only okay but that it was normal to express and not repress such emotions. The importance of being therapeutically connected to an emotionally available therapist who is self-reflective enough to engage in emotionally explicit communication cannot be overestimated. The birth of the offender working at a therapeutic level with the trauma Thus, it not only describes the offender’s behavior but how and why that offender was born. The clinical formulation will describe: Most people have a narrative of their lives which has been constructed through a combination of experience and the interpretation and recollection of others, particularly parents and siblings. Most forensic patients have distorted narratives of their lives and the links between their experiences, thoughts, emotions and behavior. Thus, the clinical formulation becomes a vehicle through which a collaborative coherent narrative of the patients life can be developed. The emphasis within individual therapy is upon developing an emotionally intimate attachment relationship in which the aetiological factors of the dysfunctional behavior can be explored and addressed by working therapeutically at an emotional level. This allows the offender to experience empathy at the level of affective attunement (that is, feeling with the person) rather than solely at intellectually understanding how difficulties have arisen. Almost all offenders in addition to experiencing attachment difficulties have experienced childhood trauma. Trauma is a key factor in the aetiology of disturbed and disturbing behaviors [14-15] describes children abused within their families who experience a familial climate of pervasive terror. Terror can also be the experience of children abused outside the family who have no physical or emotional refuge. Such terror inhibits a childrens normal development as they make adaptations to their ways of thinking, managing emotions, development of identity, managing interpersonal relationships and behaving, whilst maintaining the optimum proximity to their care givers to ensure survival. These adaptations which are described by [15] as Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Chronic trauma impacts on neurobiological development, inhibiting the integration of sensory, emotional and cognitive information [16]. Whilst these adaptations are functional within abusive environments, they become dysfunctional and maladaptive when utilized within other environments. Not everyone that experiences trauma develops behavioral difficulties. Vulnerability to doing so could be genetic, or due to poor attachment relationships, other dysfunctional family constellations and/or social and cultural environments. Through this process, the individual needs to see him, or her, self as a victim and be enabled to develop true emotional empathy and compassion for the child within the individual that experienced that trauma. Without being able to develop that empathy for the victim within the individual, he or she will not be able to develop emotional empathy for any victim. Therefore, change at a cognitive level may bring about initial change in behavior but will not bring about enduring risk reduction as, whenever the trauma is triggered, the individual will again become vulnerable to offend. Often when people undertake therapy on their own victim experience, they can become enmeshed in that experience and find it difficult to move on and take responsibility for their offending. Whilst working on the victim issues is essential to develop empathy and compassion for self as a victim, it is also essential to take full responsibility for offending and the damage done to others by that offending? Offenders can be reluctant to move to this stage as it involves the most painful emotions of shame, guilt and remorse. Offenders often actively get tuck in the victim stage as they find it so emotionally aversive to move through to taking more than verbal responsibility for their offending behavior. Therapists can also be reluctant to move onto this phase of therapy as they have developed such strong attachment to the child victim within the offender. Having developed a collaborative understanding of the birth of the offender, to then see the person that they have developed this close attachment with as an offender, can be distressing for the therapist. They may try to protect the offender from experiencing the shame and guilt of the offences that have been committed. Nonetheless, it would be unethical of the therapist not to enable the individual to take the level of responsibility needed for the offences they have committed and the victims that they have created. To do so require the offender to explore their offending in depth. A useful strategy to ensure that they develop emotional empathy and compassion is to use transformational chair work [18]. Transformational Chairwork is based on the belief that there is a healing and transformative power in giving voice to one’s inner parts, modes, and selves and in enacting or re-enacting scenes from the past, the present, or the future. To tell the offender the impact on the victim will have little impact, as the offender will defend him or herself from that knowledge at an emotional level [19]. Stated, Nobody can stand truth if it is told to him. Truth can be tolerated only if you discover it yourself because then, the pride of discovery makes the truth palatable. Transformational Chair work is a highly powerful technique and enables the individual the access the more unconscious aspects of beliefs about, aspects of self, beliefs about others and perception of relationships. Importantly, it enables the offender to truly discover the true emotional impact on his or her victim/s. The offender describes the offence he or she committed from the perspective of an outside observer. The offender and the therapist then discuss the scene to clarify the details. An empty chair is then brought in for the victim and the offender and the victim have a two-chair dialogue about the experience with the offender taking both roles. Remorse is both internal and external, I feel remorse that part of myself is capable of damaging others and remorse for having hurt others. Guilt and remorse can only come when a person is able to develop compassion and empathy. Shame is carried within the self and is associated with an internal sense of defectiveness, incompetence or inadequacy. The more self-knowledge that is developed through therapy, the more a person is able to understand and develop effective emotional regulation, the more the person can take responsibility for the self and their own choices and actions, the more effective the change. For enduring risk reduction, the internal risk factors must be addressed and then the external risk factors will be far less relevant. When through a collaborative clinical formulation, through individual therapy and the development of a secure attachment relationship and through working therapeutically on trauma and the impact of trauma on the individuals development and the birth of the offender, the individual develops true self-knowledge and self-compassion and empathy, there will be no high-risk situations. This is because the individual will be able to appropriately express and modulate emotion. If triggered the person will also and know them well enough to be able to work out what has triggered them and act appropriately. This means that in developing empathy and compassion and taking responsibility for self, the risk of that individual offending directly against another person is highly unlikely. Such a relationship is needed to make the fundamental changes in brain structure that will enable lasting change. In order to do so effectively, the therapist needs to be able to develop an authentic emotional connection to the client and be genuinely empathetic at the level of affect. Such a therapeutic relationship will require that the therapist is acutely self-aware so that a real differentiation can be made between what emotion genuinely belongs to the client and what emotions are being triggered that belongs to the therapist. It is also important that the therapist is aware of their own distorted beliefs so that these beliefs do not become incorporated into the clients formulation. This focus on the interpersonal interaction requires that therapists have had some level of personal therapy so that they are at least aware of their own issues so as not to impose these into the relationship with the client. Therapy enables therapists to examine their blind spots and work through their own issues so as not to act them out with the client [22]. Whilst it is part of the qualification that psychotherapists and counselors have therapy, personal therapy is not part of the qualification criteria for psychologists. As it is most frequently a psychologist that work therapeutically with forensic clients, in the community, in prisons and in hospitals, it is often those who have had the least personal therapy that are working with the most complex, damaged and damaging clients and those clients who are most likely to trigger issues in anyone with whom they are in any form of relationship. 1.

Rousmaniere

T and Wolpert M. Talking Failure in Therapy and Beyond (2017) The Psychologist

30: 40-43. 2.

Mews

A, DiBella L and Purver M. Impact evaluation of the prison-based core sex

offender treatment programme (2017) Ministry of Justice Analytical Series. 3.

Lambert

M and Dean EB. Research Summary of the therapeutic relationship and

psychotherapy outcome (2001) Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice and

Training 38: 357-361. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.38.4.357 4.

Psychotherapy

Research (2005) Special Issues: The Therapeutic Relationship 15. 5.

Moran

K, McDonald J, Jackson A, Turnbull S and Minnis H. A study of attachment

disorders in young offenders attending specialist services (2017) Child Abuse

and Neglect 65: 77-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.01.009 6.

Schore

A. Affect Regulation and the Origin of the Self, Routledge, New York, USA. 7.

Sameroff

A. The transactional model of development: How children and contexts shape each

other (2009) American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, USA. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/11877-000 8.

Bateman

A and Fonagy P. Randomized controlled trial of outpatient mentalization-based

treatment versus structured clinical management for borderline personality

disorder (2009) Am J Psyi 166: 1355-1364. 9.

Anderson

SW, Bechara A, Damasio H, Tranel D and Damasio AR. Impairment of social and

moral behavior related to early damage in human prefrontal cortex (1999) Nat

Neurosci 2: 1032-1037. https://doi.org/10.1038/14833 10.

Dolan

RJ. On the neurology of morals (1999) Nat Neurosci 2: 927-929. https://doi.org/10.1038/14707 11.

Cozolino

L. Attachment and the developing social brain (second edition) (2014) Norton

Series on Interpersonal Neurobiology, London. 12.

Cozolino

LJ and Santos EN. Smith college studies in social work (Why we need therapy and

why it works: A neuroscientific perspective) (2014) 84: 157-177. https://doi.org/10.1080/00377317.2014.923630 13.

Bierer

L, Yehuda R, Schmeidler J, Mitropoulou V, New A, et al. Abuse and neglect in

childhood: relationship to personality disorder diagnoses (2003) CNS Spectrums

8: 737-754. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852900019118 14.

Siegel

DJ. Toward an Interpersonal Neurobiology of the Developing Mind: Attachment

Relationships, Mindsight, And Neural Integration (2001) Infant Ment Healt J 22:

67-94. 15.

Herman

J. Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence-From domestic abuse to

political terror (2015) Basic Books, New York, USA. 16.

Vasterling

J and Brewin CR. Neuropsychology of PTSD Biological, Cognitive, and Clinical

Perspectives (2005) Guildford Press, New York, USA. 17.

Craparo

G, Schimmenti A and Caretti V. Traumatic experiences in childhood and

psychopathy: a study on a sample of violent offenders from Italy (2013) Eur J Psychotraumatol

4: 10. 18.

Kellog

S. Transformational Chairwork: Using Psychotherapeutic Dialogues in Clinical

Practice (2018) Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Lantham, Maryland. 19.

Perls

F. Delivered Finding Self Through Gestalt Therapy as part of the Cooper Union

Forum Lecture Series: The Self (1957) New York City, USA. 20.

Paivio

SC and Greenberg LS. Resolving unfinished business: Efficacy of experiential

therapy using empty-chair dialogue (1995) J Consult Clin Psychol 63: 419-425. 21.

Staub

E. A conception of the determinants and development of altruism and aggression:

Motives, the self, and the environment, (Ed) Puka B (1994) Garland, New York,

USA, Pp: 11-39. 22.

Yalom

ID. The gift of therapy: An open letter to a new generation of therapists and

their patients (2002) HarperCollins, New York, USA. Jacqui Saradjian, Consultant Clinical

and Forensic Psychologist, 1-2-3 Working Together, 3rd Floor, 207 Regent Street,

W1B 3HH, London, UK, Tel: 07534351555, E-mail: 1-2-3WORKINGTOGETHER@consultant.com Ul

Lah A and Saradjian J. Proven strategies for engagement, effective change and

enduring risk reduction with offenders (2018) Edelweiss

Psyi Open Access 2: 5-9 Clinical psychiatry, Forensic psychiatry, Mental

illness and Mental health.Proven Strategies for Engagement, Effective Change and Enduring Risk Reduction with Offenders

Asad

Ul Lah and Jacqui Saradjian

Abstract

Full-Text

Introduction

Strategies for engagement

Case Material

Strategies for effective change

During the initial phases of therapy, the clinical formulation is begun and developed. This is a dynamic document and changes as more information is gathered in the process of the therapy. The clinical formulation will describe offender’s presenting problems and use psychological theory to explain the causes and maintaining factors of those problems.

• The presenting issues;

• The offender’s life history

• Within a psychological framework indicate the factors that act to create the vulnerability or precipitate the problems developing

• The factors that are helping to maintain the problems

• The positive characteristics and resilience factors of the offender

• The interventions that will most support that offender to change Case material

Strategies for enduring risk reduction

Taking responsibility for offending - the death of the offender

Case material

This does not mean that the individual will not be able to offend again, in any way; indeed, anyone of us could offend if we chose to do so. Case material

Conclusions

References

Corresponding

author:

Citation:

Keywords