Introduction

More than 30 years ago

Antonovsky introduced the concept Sense of Coherence (SOC) [1-3]. He defined

SOC as “global orientation that expresses the extent to which one has a

pervasive, enduring though dynamic feeling of confidence that the stimuli

derived from one’s internal and external environments are structured,

predictable and explicable; the resources are available to meet the demands

posed by these stimuli and these demands are challenges, worthy of investment

and engagement”. It was a salutogenic point of view emphasizing a subject’s

protective resources and factors promoting health.

The original 29-item

SOC scale is comprised of three subscales [1,3]:

- Comprehensibility (11 items): The extent to which the social world is interpreted

as rational, understandable, structured, ordered and predictable; a dimension

referring to cognitive controllability of one’s environment.

- Manageability (10 items): The extent to which individuals consider resources

to be personally available to help them cope adequately with demands, stimuli,

and problems.

- Meaningfulness (8 items): This motivational component assesses whether a

situation is appraised as challenging and whether it is worth making

commitments and investment to cope with it.

The intention of

Antonovsky was to let the total sum-score represent the concept of SOC rather

than the subscale sum-scores. Antonovsky’s SOC focuses on the origins of health

and well-being rather than disease and as such constitutes the basis of the

salutogenic model [1]. People with a strong SOC seem to have the capacity of

dealing better with stressors of everyday life and to use available resources

to cope with these stressors [4]. This ability of coping may lead to better

health for people with a higher SOC. Although the evidence for the effect of

SOC on health is yet insufficient, groups with low SOC seem particularly

vulnerable to difficulties in life, leading to poorer lifestyle choices,

increased disease incidence and increased mortality [5-8]. SOC has been linked

to quality of life and perceived health, in particular mental health, in two

systematic reviews [9,10]. SOC seems to have a modifying influence on mental

health outcomes.

In a study of people

who had faced early childhood deprivation during the Holocaust, SOC moderated

the association between early life deprivation and post-traumatic stress in old

age [11]. A strong SOC could therefore be an important coping resource for

remaining healthy [12]. Furthermore, SOC could be modified through intervention

programs, [13,14]. A Finnish study compared employees aged 31-51 years with

burnout-symptoms with regard to two different interventions with similar aims

of reflecting the participants values, goals, beliefs and patterns of

behaviour. After 9 months both intervention groups showed a significant

increase in SOC compared with the control group [14].

A 12-month lifestyle

intervention program was implemented among persons with psychiatric

disabilities aged 22-71 years. Structured activities with sufficient level of

challenge contributed significantly to an increase in SOC, compared with the

control group [13]. Even if the number of studies is small, the results suggest

that interventions can influence SOC levels, also at old age, and that

promotion of health might benefit from strengthening of SOC [15]. SOC can also

be regarded a social concept that relates to socio-demographic factors [3].

According to Antonovsky’s theory, SOC develops along with experiences through

childhood, adolescence and adulthood and could in favorable circumstances reach

a stable level after the age of 30 years [3]. Volanen, et al., [16] found that

SOC increased with age and was most stable among the oldest subjects.

Gender differences have

been reported from SOC research. Some earlier studies found stronger SOC among

boys and men compared to girls and women [17]. Furthermore, women have been

reported to be less happy, less educated, less employed, and more distressed

with a lower SOC [18]. However, gender differences in SOC have not been consistently

reported [19]. Another study concluded that good social relationships

contribute to SOC [20]. Partnerships through cohabitating and marriage may

influence SOC and generally, those subjects living with a partner had higher

SOC-scores [16]. SOC has been shown to be related to socio-economic factors

[20]. A positive but small relationship between income and SOC among women was

reported from Canada [21]. According to Geyer, a strong SOC is shared by people

who are well educated and have higher socio-economic positions [22].

Consequently, he

proposed that high SOC should predominantly be present in higher social classes

and suggested that the SOC measures social status [22]. Deprived areas are

often associated with low social integration and poor social control. Low

social integration may lead to a sense of meaninglessness, which can give rise

to poor mental health, suicide and violent death [23]. However, Remes, et al.

found that SOC can moderate the association between area deprivation and

General Anxiety Disorder (GAD) in women [12]. Mental disorders have been found

to be associated with SOC; a strong SOC was negatively associated with anxiety,

depression and post-traumatic stress disorder [10]. Similar results were

reported by Frenz, et al., (1993) [24] and Henje Blom, et al., (2010) [25].

Furthermore, lasting

characteristics such as personality traits have been shown to be involved,

influencing both SOC and depression. The same study showed that SOC was

strongly negatively correlated with levels of trait anxiety [26]. It has been

suggested that depressive symptoms are strongest related to the Meaningfulness

factor and anxiety symptoms strongest to the Comprehensibility factor [27].

Furthermore, SOC is related to psychotic disorders and substance use disorders

as well [28]. Low SOC has been found to be a predictor of alcohol dependence

[29]. However, one study found that a strong SOC was significantly related to

not reporting dependence in 4,630 current drinkers [30]. Antonovsky suggested

that 13 of the 29 items could serve as a shorter version of the original scale

[1]. Thus, the SOC scale exists in at least in two forms; the original 29-item

SOC scale (SOC-29) and the 13-item SOC scale (SOC-13). SOC-13 has five items

concerning Comprehensibility, four items concerning Manageability, and four

concerning Meaningfulness. To the best of our knowledge Antonovsky himself

choose the 13 items but it is unknown why these particular items were chosen.

Pallant and Lae (2002) [31] recommended the 13-item scale when time or space

limitations prevented use of the full scale. Eriksson and Lindström (2005) [32]

showed that the 29-item SOC scale and the 13-item SOC scale version are valid

and reliable instruments to assess how people manage stressful situations and

stay well. However, Jakobsson (2011) [33] did not find acceptable construct

validity for the 13-item SOC and remarked that this version may not be

representative of SOC theory.

The aim of this study

was to determine if a reasonable explanation could be found why the particular

13 items were selected for the SOC-13 scale. This was done by comparing how

well socio-demographic variables and mental disorders related to sum-scores of

SOC-13, SOC-29 and sum scores of the excluded 16 items (SOC-16), and how well

the sum-scores correlated with each other. Furthermore, we investigated if the

single items from SOC-13 related stronger to sociodemographic and mental health

variables than the single items from SOC-16. Finally, for each item we

investigated the distribution of the responses in order to search for

differences between the two sets of items.

Material and Methods

The

Lundby Study

The Lundby Study is a

prospective study of mental health in an unselected population consisting of

subjects living in the south of Sweden. It started 1947, comprising 2,550

subjects living in a geographically defined area. In (1957) 1,013 subjects who

had moved into the area were added to the cohort; subsequently the cohort

comprised 3,563 subjects. Since then, no subjects have been added [34]. All

subjects were followed in later field-investigations, regardless of domicile.

In the follow-up in 1997, the last field-investigation, the population included

1,797 living subjects aged 40-96 years.

All subjects were

investigated by a semi-structured interview. In 1997, introductory letters were

sent to the subjects in the cohort. Subjects were contacted by telephone, and

appointments were scheduled with participants. Experienced psychiatrists

conducted the interviews at home, starting with questions about the

individual’s physical and mental health and contact with healthcare providers.

Mental health assessment included substance abuse disorder, also alcohol use

disorder. Additional information was obtained through relatives or other key

informants, such as general practitioners and from official registers including

hospital case notes (psychiatric and non-psychiatric) [35].

Sociodemographic

Assessment

Gender and age were

registered. Civil status is here categorized into living alone or living with a

partner. The subjects were categorized into three socio-economic levels:

blue-collar workers (unskilled, semiskilled and skilled workers); white-collar

workers (assistant non-manual employees, employed and self-employed

professionals, higher civil servant and executives) and self-employed workers

(other than professionals).

Diagnostic

Assessment

The subjects were classified

according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,

(DSM-IV) and according to the Lundby diagnostic system, a diagnostic system

adapted to fieldwork [35,36]. In the present study, the diagnoses were grouped

into the following categories: depressive disorders, anxiety disorders,

somatoform disorders, organic disorders, psychotic disorders, dementia, alcohol

use disorders and personality disorders.

Depressive disorders

correspond roughly to the diagnosis of major depression in the DSM-IV and

anxiety disorders comprised of generalized anxiety disorders, panic disorders,

and social phobia. Somatoform disorders included undifferentiated somatoform

disorder and pain disorders. Organic disorders included syndromes with

cognitive deficits, such as memory difficulties, slow or delayed reactions, and

concentration difficulties (e.g. cognitive disorder NOS). Psychotic disorders

in the Lundby Study included schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders

including manic states. Dementia included multi-infarct dementia, Alzheimer’s

disease and other varieties of dementia. Alcohol use disorders were comprised

of alcohol use disorder and alcohol dependence. Personality disorders

correspond to personality disorders according to the DSM-IV.

SOC

Assessment

The Antonovsky SOC

scale has been translated into many languages and has been in use worldwide

[10]. A Swedish version of the original 29-item SOC and the 13-item scale has

been in use since 1990 and was utilized in the present study [37]. Each item in

the SOC questionnaire is scored from 1 to 7, the total score ranges from 29 to

203; higher scores indicate stronger SOC. The questionnaire was given to

participants after the interview with a request for it to be completed later

and returned by mail [35]. Thus, the psychiatrist was not present when the

participant completed the questionnaire.

Statistics

The socio-demographic

variables in the sample were described using medians and quartiles, as well as

with absolute and relative frequencies. Sum-scores for SOC-13, SOC-16 and

SOC-29 were calculated. Linear regression models were used to investigate how

demographic factors could explain the variations in the sum-scores of the

SOC-13 and SOC-29. The relationships between the sum-scores for SOC-13, SOC-16

and SOC-29 and age were calculated using Spearman’s correlation. The

relationships between the sum-scores for SOC-13, SOC-16 and SOC-29 and

socio-demographic variables other than age were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney

U-test and the Kruskal-Wallis test. Spearman’s correlations were used to

evaluate the relationships between age and the individual items.

The Mann-Whitney U-test

and the Kruskal-Wallis test were used to investigate the relationships between

the individual items in the SOC questionnaire and socio-demographic factors and

mental disorders. We calculated mean, standard deviation, and skewness of the

responses for each item and compared the means of these characteristics for the

items in SOC-13 with the means of the characteristics for the items in SOC-16.

This was done for individuals without and with a mental diagnose, and for all

individuals together. We investigated the prevalence of missing answers on the

SOC-13, SOC-16 and SOC-29 in relation to socio-demographic factors.

P-values<0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Participants

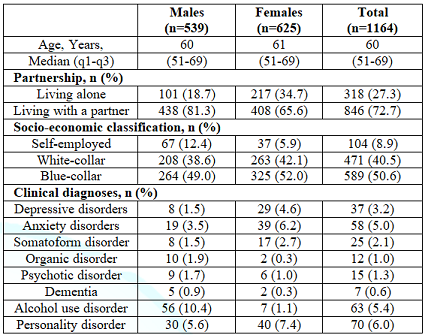

In 1997, 1,559 of 1,779

(87.6%) participants were interviewed and 1,164 (65.4%) completed the SOC

questionnaire. The sociodemographic factors and the point prevalence of mental

disorders are presented in Table 1. Median age was 60 years (inter quartile

range, 51-69 years). Most participants were living with a partner (72.7%). Less

than 10% were self-employed, around 40 % were white-collar and around 50% were

blue-collar workers. The most common prevalent mental disorders were

personality disorder (6.0%), alcohol use disorder (5.4%), anxiety disorder

(5.0%) and depressive disorder (3.2%). More women were living alone and

suffered more from depressive, anxiety and somatoform disorders compared to

men. On the other hand, alcohol use disorder was more prevalent among men. The

questionnaire was not completed for 395 persons, who were considered as

drop-outs.

The drop-outs were often males, unmarried and blue-collar workers. Slightly fewer subjects among the dropouts in comparison to those that filled in the SOC were diagnosed with a mental disorder; however, the prevalence of alcohol use disorder was somewhat higher among dropouts compared to participants (6.8% vs. 5.4%).

Relationships

between SOC Sum-Scores, Socio-Demographic Factors and Mental Disorders

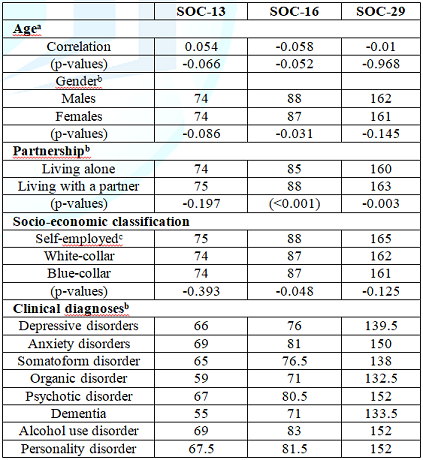

Relations between

socio-demographic factors and mental disorders on the one hand and sum-scores

on SOC-13, SOC-16 and SOC-29 on the other are presented in in Table 2.

No significant

relationships were obtained between SOC-13 and the socio-demographic factors,

except for age, where there was an almost significant (p=0.066) positive

correlation. In contrast, the sum-score for SOC-16 was negatively and almost

significantly correlated with age (p=0.052); but SOC-16 was also significantly

correlated with the remaining three sociodemographic factors, giving higher

values to men, those living with a partner and self-employees. Partnership was

the only factor significantly correlated with SOC-29, giving those with a

partner higher value. Individuals with a diagnosis of a mental disorder had

significantly lower scores on all three SOC scales. The diagnoses with the

lowest SOC scores were organic disorder, dementia, somatoform disorder and

depressive disorder. Linear regression models relating the sociodemographic

variables to SOC-13 and SOC-29 sum-scores as dependent variables were analysed.

The regression coefficients for age and partnership were significant (0.07,

p=0.022 and 1.62, p=0.040, respectively) for the SOC-13 sum-score. Only

partnership was significantly associated with the SOC-29 sum-score (regression

coefficient 5.16, p=0.001), whereas age was not significantly related to the

SOC-29 sum-score after controlling for partnership.

Relationships

between Sociodemographic Variables and Each of the 29-Items

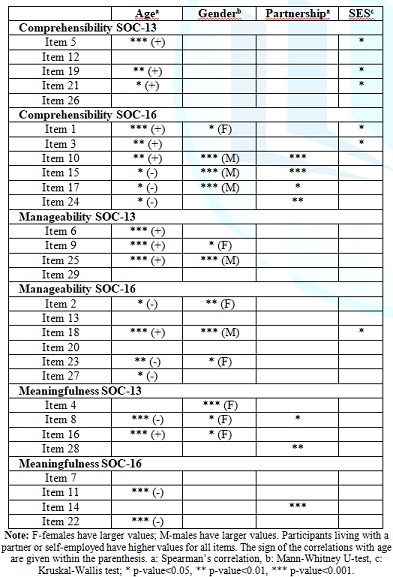

The significances of the associations between the items in the questionnaire and the socio-demographic variables are presented in Table 3, separated into the three subscales. Much strong significances were found in the relationships to age for both SOC-13 and SOC-16, within all three subscales.

However, the directions

of the relationships differed, among SOC-16 most items with negative

correlations appeared. Gender significances were observed in the

comprehensibility subscale only for some items from SOC-16, mainly giving males

higher values. For items from the manageability subscale, no clear difference

was found between SOC-13 and SOC-16 in relations to gender. Finally, females

generally scored higher on items in the SOC-13 for the meaningfulness subscale.

There were significances for partnership on SOC-16 items in comprehensibility;

and in both the SOC-13 and SOC-16 for meaningfulness. No strong significances

for socio-economic status were detected, neither for SOC-13 nor SOC-16. Some

weak associations were found in the comprehensibility scale, where blue-collar

workers had higher values both on SOC-13 and SOC-16.

Relationships

between Mental Disorder Diagnoses and Each of the 29 Items

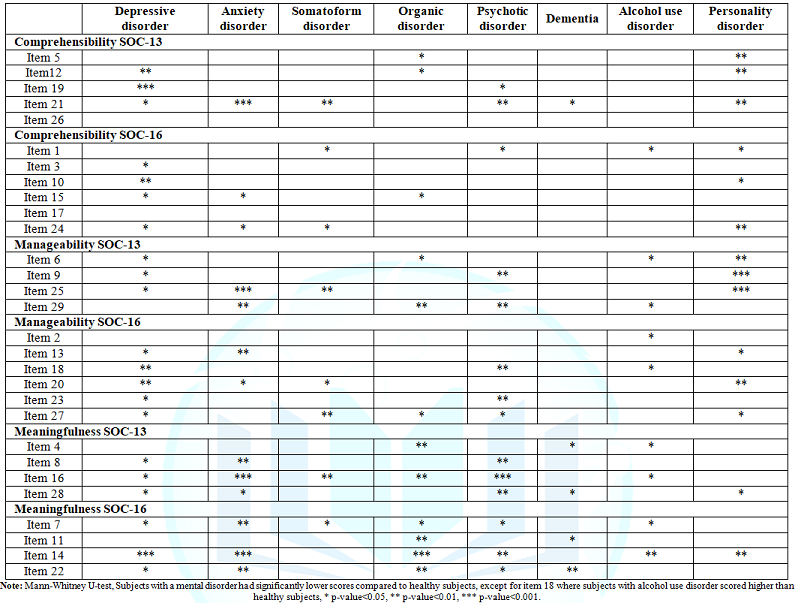

The majority of the

items related significantly to a mental disorder with no clear distinction

between SOC-13 and SOC-16 items. For depressive disorder, anxiety disorders or

somatoform disorder there were no substantial distinctions in correlations to

SOC-13 and SOC-16 items. Depressive disorder in the manageability subscale was

slightly more correlated to SOC-16 items than to SOC-13 items. Organic

disorders showed stronger correlations in SOC-16 items from the meaningfulness

subscale.

Psychotic disorders

correlated more often to SOC-13 items in the meaningfulness subscale than to

SOC-16 items. Few significant correlations were found for dementia, whereas

personality disorders correlated higher to items in SOC-13 from the

manageability subscale (Table 4). Pearson’s correlation coefficient between

sum-scores for SOC-13 and SOC-16 was 0.817. SOC-13 had a somewhat lower

correlation (0.576) to SOC-16 for the comprehensibility subscale. The

correlation between SOC-13 and SOC-16 was 0.593 for the manageability subscale,

and 0.717 for the meaningfulness subscale.

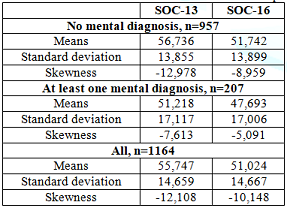

In table 5 we compare

the mean values of the statistical characteristics mean, standard deviation and

skewness of responses for items belonging to SOC-13 and to SOC-16 for

individuals with and without a mental diagnose, and for all individuals

together. In general, the means of items belonging to SOC-13 were higher than

the means for items belonging to SOC-16; the standard deviations were more or

less equal. The skewness values revealed that the distributions were generally

more negatively skewed for items in SOC-13. Mean values were in general lower

and the distributions of the items were less skewed for those with a mental

illness. The number of missing values was low. A tendency towards more missing

values for items in SOC-13 compared to items in SOC-16 was found (result not

shown). In total, 1,090 subjects had no missing values, 63 had 1 missing value,

5 had 2, 3 had 3, and 3 individuals had 4 missing values.

There were in total 94

(0.28%) missing values. The occurrence of missing values was not related to

gender, partnership, or socioeconomic status. However, a significant positive

correlation was observed between age and the number of missing values; those

with no missing values had a mean age of 59.9 years, while those with 1-4

missing values had a mean age of 66.2 years (p<0.001).

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to explore why the specific 13 items were selected for the shorter version of the SOC. According to the theory, SOC could be seen as a way of viewing life leading to the deployment of coping strategies in stressful situations. Subjects with good generalized resilience resources could be expected to frame the world as organized and understandable and could be fit to meet stressful conditions. SOC could be considered a social concept used in the field of mental health.

Socio-demographic

factors and mental health have been shown to be related to SOC scales [12,20].

Therefore, it was important to determine if the 13 items selected for the

shorter SOC were more sensitive to variations in socio-demographic factors and

mental health compared to the remaining 16 items. This was accomplished by

comparing the relationships between the socio-demographic factors and the total

scores on the SOC-29, SOC-13 and SOC-16 and by studying the relationships

between the socio-demographic factors and individual items within the three

subscales manageability, comprehensibility and meaningfulness. The

relationships between SOC and mental disorders were investigated in a similar

way. Finally, it was interesting to see if the distributions of the responses

for the 13 items differed from those for the responses on items in SOC-16. We

found different relationships between the sociodemographic factors (gender,

partnership, socioeconomic status and age) and total SOC scores.

SOC-13 did not relate

significantly to any of the factors, SOC-29 related to age, whereas the total

scores constructed by SOC-16 showed significant relationships with all factors

considered. The study of the individual items clarified where the differences

occurred. The values of items belonging to SOC-13 were in general higher than

the values of items belonging to SOC-16 and the distributions were more

negatively skewed for items in SOC-13. Researchers have found different results

regarding associations between age and SOC. It has been suggested that the

second and third decade of life are crucial formative years for the development

of SOC [38].

However, it has been

debated whether SOC remains stable. Some has found that SOC tends to increase

with age over the lifespan [32]. However, on the other hand older age can be

associated with losses, loneliness and deteriorating health, suggesting SOC

could decrease; no significant association was found between age and the SOC-29

sum-score. In our study, several items were highly significantly related to

age; SOC-13 was generally increasing with age, whereas SOC-16 was decreasing

with age. Accordingly, when these two sum-scores were added no significant

correlation remained between age and the sum-score for SOC-29. Due to the

differences in the relationship to age found here for the specific items in the

questionnaire, it appears that the association between age and SOC is not well

captured by the sum-scores.

Higher SOC-scores were

detected for males in comparison to females among Swedish adults aged 60 and 70

years [4]. We found no significant relationships between gender and the SOC-13

and SOC-29 sum-scores; however, males had slightly, but significantly higher

sum scores than females using the SOC-16 (see table 2). The reason for the lack

of significance was understood by looking at the specific items. Males scored

higher on some items but females higher on other items; by creating the

sum-scores these differences vanished. The gender differences appeared

particularly within the subscales; males had higher values than females on the

comprehensibility subscale, but not on the manageability subscale; males had

lower scores on the meaningfulness subscale (see table 3). It is not easy to

explain these differences.

A Finnish study found

that psycho-emotional resources rather than socio-economic circumstances

associated with SOC in both men and women [16]. Thus, neither sum-scores of

SOC-13, SOC-16 nor SOC-29 were suitable to address gender differences; the

sub-scales or possibly specific items should be investigated to understand the

relationship between gender and SOC. Partnership seems to influence SOC. A

study based on SOC-13, concluded that good social relationships and high SOC

are influencing each other [16]. Furthermore, a study using SOC-29 reported

that family-related variables contributed to the explanation of SOC [39]. This

is in line with our results; partnership gave higher values on most items in

the questionnaire. The manner in which relationships are perceived can in

particular influence the way the comprehensibility subscale is answered.

However, the strongest

statistical associations were found in this study for items belonging to

SOC-16; indicating that SOC-16 is probably better than SOC-13 to study the

influence of partnership on SOC. SOC was thought to be stronger for people

raised in a stable home with clearly defined cultural norms [1]. However,

earlier findings from the Lundby Study showed that subjects with what was

considered a high-risk childhood had SOC scores comparable to the scores of

those from the middle class [37]. It is possible that the strength of SOC is

shaped by life experiences in childhood and adolescence but can be modified by

environment such as working conditions [38].

An earlier study

suggested that the stability of an individual’s SOC might be open to the

influence of position in the occupational hierarchy, even after the age of 30

years [40]. Clear associations have been reported between SOC scores and social

classes, in particular occupation. Prospective population studies have shown

that lower socio-economic position is leading to poorer health among people

compared to those at higher socio-economic levels [41]. Unskilled occupational

positions have been shown to increase the risk for lower SOC scores relative to

professional and semi-professional occupations [17]. SOC scores are highest

among those with a high social position and good education [22]. There exists

evidence that stabilization of SOC associates with stabilization of the labour

market position, moreover, the fluctuations of SOC seem to depend on the type

of trajectory throughout adult life [42].

Thus, a more favorable

development of SOC could be seen among those whose trajectories were directed

upward. The associations of poor SOC with unemployment were evident, whereas

the effects of fixed-term employment seemed to be neutral or even positive. In

the present study, we found weak relationships to socioeconomic status and no

profound differences between sum scores for SOC-13 and SOC-29. However, as the

sum-score for the SOC-16 was significantly related to socioeconomic status it

is not obvious that SOC-13 or SOC-29 are more informative than SOC-16. Sweden was

a fairly equal society at the time of the study, which may explain the weak

correlations found here.

Furthermore, with the

median age of 60 in this study many participants were above the retirement age

and thus out of occupation and enjoying a fairly generous retiret system. It

has been suggested that SOC does not capture a salutogenic construct but could

rather be used as a measure of emotionality [43]. SOC has been found to have an

inverse relation to mood and anxiety disorders [25]. The findings are in

accordance with studies reporting that strong SOC is associated with a reduced

risk of psychiatric disorders [8]. In the present study we found strong

associations between mental disorders and all three SOC-scales considered here.

No clear distinction could be seen between SOC-13 and SOC-16.

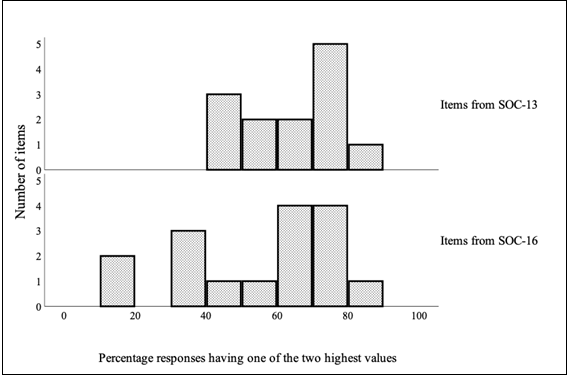

The distributions of the responses for the 13 items differed from the responses for the items in SOC-16 in such a way that the responses of the items were generally higher for items in SOC-13 and the distributions of responses more negatively skewed. It is noteworthy that the means were generally very high and close to the maximal value of 7, for instance 5.57 and 5.10 among all individuals for SOC-13 and SOC-16, respectively. This implies that most individuals use only the highest values and not the full range from 1 to 7, and in particular so for items in SOC-13. Further analysis showed that in 6 of the 13 items more than 70% answered 6 or 7; while in 5 of 16 items more than 70% answered 6 or 7 (see Figure 1).

The question arises if

the skewness depends on how the response possibilities were formulated. No

explicit words describe the alternatives except for the endpoints, leading to

difficulties choosing values other than the extremes. Expectations form the

social environment may also influence the tendency of giving higher values on

the items. There is also the possibility of psychological mechanisms such as

wishful thinking influencing the answers.

Conclusions

SOC has been considered

a social concept, also used in mental health; therefore, SOC sum-scores would

be expected to relate to socio-demographic factors and mental diagnosis.

However, in the present study different results were obtained, depending on

which of the three scales (29,13,16) were used. In particular, the SOC-16

appeared to be sensitive to differences in socio-demographic factors. In

general, the individual items related similarly to partnership and to some

extent to socio-economic status, but strong inconsistencies were found for the

relationships to age and gender. It was not possible to find a clear

distinction regarding how the items in SOC-13 and SOC-16 related to mental

disorders.

Thus, we found nothing

suggesting that the items in SOC-13 were more informative than the 16 excluded

items. The responses for the items were concentrated on the highest values for

many items, and relatively more so for the SOC-13. The question arises if this

depends on how the items were formulated, and if expectations from the social

environment play a role. It is important to consider what scale to use in

studies of socio-demographic factors. One could, depending on the aim, choose

items, in particular those where respondents use the full scale. More research

is needed concerning the operationalization of the SOC concept.

Strength and Limitations

The cohort was comprised of an unselected, geographically defined population. There were few dropouts in the follow-up, diminishing selection bias. There were few missing values in the SOC-questionnaire. SOC-13 was not applied on its own but was inherent in the SOC-29.

References

- Antonovsky A. Unravelling the mystery of health

(1987) San Francisco: Jossey Bass, California, USA.

- Antonovsky A. Health Stress and coping (1979) San

Francisco: Jossey Bass, California, USA.

- Antonovsky A. The structure and properties of the

sense of coherence scale (1993) Soc Sci Med 36: 725-733.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(93)90033-Z

- Lindmark U, Stenström U, Gerdin EW and Hugoson A.

The distribution of “sense of herence” among Swedish adults: a quantitative

cross-sectional study (2010) Scand J Public Health 38: 1-8.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494809351654

- Surtees PG, Wainwright NWJ and Khaw KT. Resilience,

misfortune and mortality: evidence that sense of coherence is a marker of

social stress adaptive capacity (2006) J Psychosom Res 61: 221-227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.02.014

- Wainwright NW, Surtees PG, Welch AA, Luben RN, Khaw

KT, et al. Sense of coherence, lifestyle choices and mortality (2008) J

Epidemiol Community health 62: 829-831.

https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2007.066464

- Poppius E, Tenkanen L, Hakama M, Kalimo R and

Pitkänen T. The sense of coherence, occupation and all- cause mortality in the

Helsinki Heart Study (2003) Eur J Epidemiol 18: 389-393.

https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1024213427147

- Kuovonen AM, Väänänen A, Vahtera J, Heponiemi T,

Koskinen A, et al. Sense of coherence and psychiatric morbidity: a 19-year

register-based prospective study (2010) J Epidemiol Community Health 64:

255-261. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2008.083352

- Eriksson M and Lindström B. Antonovsky's sense of

coherence scale and its relation with quality of life: a systematic review

(2007) J Epidemiol Community Health 61: 938-944.

https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2006.056028

- Eriksson M and Lindström B. Antonovsky's sense of

coherence scale and the Relation with health: a systematic review (2006) J

Epidemiol Community Health 60: 376-381.

https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2005.041616

- Van der Hal-van Raalte EA, Van Ijzendoorn MH and

Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. Sense of coherence moderates late effects of early

childhood Holocaust exposure (2008) J Clin Psychol 64: 1352-1367.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20528

- Remes O, Wainwright NWJ, Surtees P, Lafortune L,

Khaw KT, et al. A strong sense of coherence associated with reduced risk of

anxiety disorder among women in disadvantaged circumstances: British population

study (2018) BMJ Open 8: e018501. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-018501

- Forsberg KA, Björkman T, Sandman PO and Sandlund M.

Influence of a lifestyle intervention among persons with a psychiatric

disability: a cluster randomized trial on symptoms, quality of life and sense

of coherence (2010) J Clin Nurs 19: 1519-1528.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03010.x

- Kähönen K, Näätänen P, Tolvanen A and Salmela-Aro K.

Development of sense of coherence during two group interventions (2012) Scand J

Psychol 53: 523-527. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12020

- Super S, Wagemakers MA, Picavet HS, Verkooijen KT

and Koelen MA. Strengthening sense of coherence: opportunities for theory

building in health promotion (2016) Health Promot Int 34: 869-878.

https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dav071

- Volanen SM, Lahelma E, Silventoinen K and Suominen

S. Factors contributing to sense of coherence among men and women (2004)

European journal of public health 4: 322-330. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/14.3.322

- Antonovsky H and Sagy S. The development of a sense

of coherence and its impact on responses to stress situations (1986) The

Journal of Social Psychology 126: 213-225.

- Anson O, Paran E, Neumann L and Chernichovsky D.

Gender differences in health perceptions and their predictors (1993) Soc Sci

Med 36: 419-427. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(93)90404-r

- Volanen SM, Suominen S, Lahelma E, Koskenvuo M and

Silventoinen K. Negative life events and stability of sense of coherence: a five-year

follow-up study of finnish women and men (2007) Scand J Psychol 48: 433-441.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2007.00598.x

- Festin K, Thomas K, Ekberg J and Kristenson M.

Choice of measure matters: A study of the relationship between socioeconomic

status and psychosocial resources in a middle-aged normal population (2017)

PLoS ONE 12: e0178929. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178929

- Ing JD and Reutter L. Socioeconomic status, sense of

coherence and health in Canadian women (2003) R Can J Public Health 94:

224-228. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03405071

- Geyer S. Some conceptual considerations of the sense

of coherence (1997) Soc Sci Med 44: 1771-1179.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00286-9

- Durkheim E. Suicide-a study in sociology (2010)

Simon and Schuster, New York, USA.

- Frenz AW, Carey MP and Jorgensen RS. Psychometric

evaluation of Antonovsky’s Sense of Coherence Scale (1993) Psychological

Assessment 5: 145-153. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.145

- Henje Blom EC, Serlachius E, Larsson, Theorell T and

Ingvar MJO. Low Sense of Coherence (SOC) is a mirror of general anxiety and

persistent depressive symptoms in adolescent girls-a cross-sectional study of a

clinical and a non-clinical cohort (2010) Health and quality of life outcomes

8: 58. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-8-58

- Hart KE, Hittner JB and Paras KC. Sense of

coherence, trait anxiety and the perceived availability of social support

(1991) J Res Pers 25: 137-145. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-6566(91)90010-n

- Sandell R, Blomberg J and Lazar A. The factor

structure of Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale in Swedish clinical and

nonclinical samples (1998) Pers Individ Dif 24: 701-711.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0191-8869(97)00225-0

- Tops A and Hansson L. The validity of Antonovsky`s

Sense of coherence measure in a sample of schizophrenic patients living in the

community (2001) J Adv Nurs 33: 432-438. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01692.x

- Midanik LT and Zabkiewicz D. Indicators of sense of

coherence and alcohol consumption- related problems: The 2000 US National

Alcohol Survey (2009) Subst use Misuse 44: 353-373.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10826080802347511

- Larm P, Åslund C, Starrin B and Nilsson KW. How are

social capital and sense of coherence associated with hazardous alcohol use?

Findings from a large population-based Swedish sample of adults (2016) Scand J

Public Health 44: 525-533. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494816645221

- Pallant JF and Lae L. Sense of coherence,

well-being, coping and personality factors: further evaluations of the sense of

coherence scale (2002) Pers Individ Dif 33: 39-48.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0191-8869(01)00134-9

- Eriksson M and Lindström B. Validity of Antonovsky´s

sense of coherence scale: a systematic review (2005) J Epidemiol Community

Health 59: 460-466. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech.2003.018085

- Jakobsson U. Testing construct validity of the

13-item sense of coherence scale in a sample of older people (2011) Open

Geriatr Med J 4: 6-13. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874827901104010006

- Hagnell O, Essen-Möller E, Lanke J, Öjesjö L and

Rorsman B. The Incidence of Mental Illness Over a Quarter of a Century: Lundby

Longitudinal Study of Mental Illnesses in a Total Population Based on 42, 000

Observation Years (1990) Almqvist and Wiksell Internat, Sweden.

- Nettelbladt P, Bogren M, Mattisson C, Öjesjö L,

Hagnell O, et al. Does it make sense to do repeated surveys?-The Lundby Study 1947-1997

(2005) Acta Psychiatr Scand 111: 444-452.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00518.x

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic

Statistical Manual of mental disorders (1994) (4th Edn) American Psychiatric

Association, USA.

- Dahlin L, Cederblad M, Antonovsky A and Hagnell O.

Childhood vulnerability and adult invincibility (1990) Acta Psychiatr Scand 82:

228-232.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1990.tb03058.x

- Feldt T, Lintula H, Suominen S, Koskenvuo M, Vahtera

J, et al. Structural validity and temporal stability of the 13-item sense of

coherence scale: Prospective evidence from the population-based HeSSup study

(2007) Quality of Life research 15: 483-493.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-006-9130-z

- Olsson M, Hansson K, Lundblad AM and Cederblad M.

Sense of coherence: definition and explanation (2006) Int J Soc Welfare 15:

219-229. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2006.00410.x

- Smith PM, Breslin FB and Beaton D. Questioning the

stability of sense of coherence: The impact of socio-economic status and

working conditions in the Canadian population (2003) Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr

Epidemiol 38: 475-484.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-003-0654-z

- Allen J, Balfour R, Bell R and Marmot M. Social

determinants of mental health (2014) Int Rev Psychiatry 26: 392-407.

https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2014.928270

- Liukkonen V, Virtanen P, Vahtera J, Suominen S,

Sillanmäki L, et al. Employment trajectories and changes in sense of coherence

(2010) Eur J Public Health 20: 293-298. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckp171

-

Schnyder U, Buchi S, Sensky T and Klaghofer R.

Antonovsky’s Sense of Coherence: Trait or State? (2000) Psychother Psychosom

69: 296-302. https://doi.org/10.1159/000012411

Corresponding author

Cecilia Mattisson, Institute of

Clinical Sciences in Lund, Department of Psychiatry, Lund University, Baravägen

1, SE-221 85 Lund, Sweden, Tel: +4646177800, E-mail: cecilia.mattisson@med.lu.se

Citation

Mattisson C, Gräsbeck

A, Bogren M and Horstmann V. Antonovsky’s short 13-items SOC scale in a Swedish

community cohort-considering the selection of the 13 items from the original 29

SOC scale (2020) Edelweiss Psyi Open Access 4: 7-14.

Keywords

Sense of Coherence, SOC-13, SOC-29, Sociodemographic factors, Mental disorders, Population-based sample.

PDF

PDF