Research Article :

Howard Moskowitz and Attila Gere The paper introduces

the science and process of Mind Genomics as a process by which to reveal the

mind of prospects regarding the factors surrounding insurance, specifically

insurance that the home contractor will complete the project satisfactorily.

The objective is to uncover the existence and nature of groups of people

sharing the same point of view about what they want in such insurance. The Mind

Genomics processes works through experimental design, presenting respondents

with vignettes, combinations of messages about insurance, totally different

combinations for each respondent. The subsequent analysis by regression reveals

which messages make the respondent feel comfortable with the project and the

insurance, versus which messages make the respondent feel insecure, and ready

to drop the project. The data suggest three mind-sets of people;

project-focused, contractor-focused, and legal/finance-focused, respectively,

responding to different aspects of the contracting relationship. We introduce

the PVI, personal viewpoint identifier, to assign a new person to one of these

three mind-sets, to aid sales and client service. Insurance

is a business, an exercise in statistics, and a game of

psychology between players, all at the same time. The academic literature about

insurance covers topics ranging from the statistical analysis of norms to the

selling of policies, and of course to the fulfillment of obligations. When

people buy insurance, they do so in hopes of never having to use it, and are at

the mercy of two competing motives, viz., best coverage and lowest cost. When

the customer is knowledgeable about the topic, or even thinks beyond the

momentary transaction, the issue comes up as to the nature of the interaction

with the insurance company should there

arise a problem for which the insurance was originally purchased. There

have been some papers on the psychology of home construction insurance [1,2].

The most instructive information about home contractor insurance comes from the

Internet, specifically from organization specializing in contractor insurance

or specific brokers. Here are three examples, phrased clearly to alert readers

to the need for such insurance. Note that these are written from the point of

view of the contractor, who must carry the insurance, and NOT from the point of

view of insuring the homeowner. Insurance.com asked 1,000 people about their

home improvement projects to see whether they were a success or failure.

Findings reveal that going over budget and not completing the work are the top

renovation fails. Of those who had a home renovation fail: 41% spent more than

expected, 39% didn’t finish an important project, 12% had arguments with their

partner or spouse as a result of the renovation, 5% experienced fire, flooding

or other damage due to the work, 2% damaged a neighbor’s property https://www.insurance.com/home-and-renters-insurance/contractor-renovation-remodel. You should

verify your contractor’s insurance coverage before hiring him or her by asking

to review a copy of the contractor’s policies. It should include both a

commercial business/general liability insurance policy and workers

compensation. The latter is important because without it, workers remodeling

your home could sue you if injured. Though your liability insurance would pay

for that, up to your limits, it’s best to avoid the situation altogether. https://www.insurance.com/home-and-renters-insurance/contractor-renovation-remodel General

liability insurance policies will usually cover a broad range of damages,

including: · Faulty

workmanship · Job-related

injury · Advertising

injury/defamation Contractors

or developers may actually be required to have a minimum level of liability

insurance either by law in some states or to win certain contracts that require

it. Companies who complete many design-build projects will definitely want to

have liability insurance in case they are sued for mistakes. Also,

subcontractors are frequently required to carry liability insurance in order to

work for certain general contractors. https://constructioncoverage.com/construction-insurance#types. The

academic literature of insurances deals with topics which are in the domain of

specialists, such as the way the customers decide about insurance, legal

issues, and other serious topics [2-5]. The subjective aspects, especially

through the theory of reasoned action, tend to be bland, without feeling,

almost as if they were presented from 30,000 feet, without the granularity of

everyday life

[6-8]. There

is a need in the academic literature for studies which deal with the emotions

of people considering insurance. The topic of insurance as an emotional issue

is not unusual because it is the emotion, the anticipation of negative results

from one’s action, or a negative situation in one’s life, which drives the

purchase of insurance. There is the tendency to delay, to rationalize,

tendencies that must be overcome through marketing and sales. Those who are

trying to sell insurance are not interested in theory, but rather in the

correct messages which ‘sell’ the insurance. For

the business person, the issue is what should be offered, and what should be

communicated about what is being offered. There is no lack of information about

what should be offered; one need only read advertisements for insurance to

understand the depth of insight into the sensitivities and soft spots of

insurance buyers, possessed by those who sell insurance. The goal of this paper

is to apply the rigorous study of communication to the offerings of an

insurance company wishing to sell contractor

insurance.

The objective is to begin a series of investigations into the nature of the

messaging of insurance from the point of view of how a typical respondent

‘feels’. The

process to understand the mind of the prospective insurance buyer followed the

steps of Mind Genomics, a newly

emerging science of the ‘mind of the everyday’ [9-11]. Mind Genomics explores

the mind of the everyday by presenting respondents with vignettes, combinations

of elements (messages, ideas), obtaining ratings, deconstructing the ratings

into the contributions of the separate elements using regression, and by so

doing revealing the mind of the respondent, standing in for the prospective

insurance purchaser. Step 1: Raw

Material

Mind

Genomics works at the granular level, with test stimuli drawn from everyday life. Step 1 is

Socratic, beginning with a set of related questions which ‘tell a story’, and

then generating four answers to each question, representing alternatives. The

exercise for this study generated the questions and answers shown in Table 1. These do not, in any fashion,

reflect the full gamut of possible questions and answers in insurance, but

rather represent a tractable set of ideas. An ingoing world-view in Mind

Genomics is that it is better to iterate quickly and inexpensively to find the

answer, rather than to create a possibly ponderous study which might implode

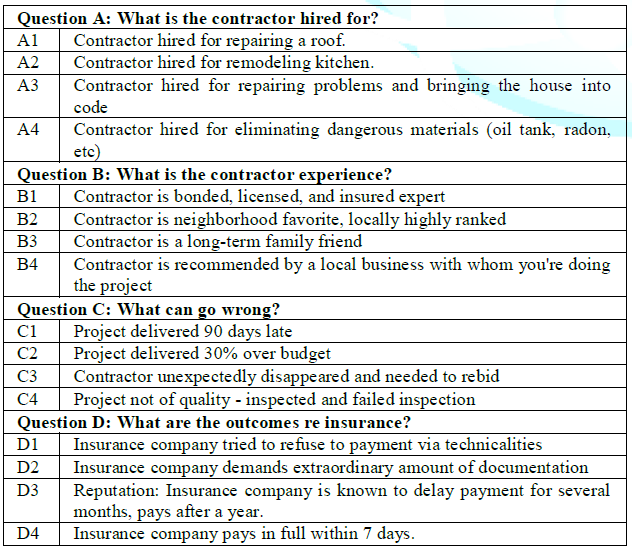

from its own gravitas. Table 1: The four

questions, and the four answers (elements) for each question. In

Mind Genomics experiments, the objective is to quickly and inexpensively

identify strong-performing elements, and when necessary move on to the next

iteration. The choice of four questions, each with four alternative answers,

the elements, is based upon the observation that larger numbers of questions

and answers at first are thought to generate a ‘better experiment’ because of

more coverage, but become self-defeating as the effort begins to be

overwhelming to fill the available slots for elements. Quite

often the larger-scale studies implode, brought to an untimely, early end by

the inability of the group to come to a resolution. This is akin to the

increasingly observed ‘paradox of choice’, where decision-making becomes hard,

even onerous when the number of possible selections increases [12]. The 4x4

design is a compromise, providing enough variation in stimulus set, but small

enough to be executed quickly, and not to be perceived as the one study which

will answer everything. Step 2:

Vignettes (Combinations of Elements) The

respondent does not evaluate single elements, the usual process in survey

research. Rather, the study is conducted in the form of an experiment, one

conducted on the computer, with the respondents evaluating combinations of

elements which represent different sets of propositions, or vignettes. The vignettes

comprise combinations of the answers, the elements (see Table 1), without,

however, the question being present. That is, each vignette presents a simple

set of elements without any attempt to connect the answers to create a coherent

but often densely worded paragraph. The experimental design combines these 16

elements into small vignettes, each vignette comprising from two to four

elements, at most one element or answer from a question. The experimental

design ensures that the elements are statistically independent of each other,

allowing the data emerging from the study to be analyzed by OLS (Ordinary

Least-Squares) regression, either at the individual respondent level or at the

group level. Each

respondent evaluated a unique set of 24 vignettes developed according to a

permutation scheme which maintained the mathematical integrity of the

experimental design, but at the same time ensured that the research covered a

great number of combinations. The permutations ensure that the Mind Genomics

experiment assesses a great number of combinations, 2400 in the case of the 100

respondents in this study. The objective is to cover a great deal of the

underlying design space. Each individual measurement is ‘noisy’ since it is

measured one time. The rationale is that by covering a great deal of the design

space through the permutation strategy, one will obtain a clearer, less-error

prone estimate of the contribution of the individual elements to the rating.

This strategy stands in opposition to the typical strategy of reducing error by

replicating the stimulus many times, thus getting a better estimate of the

measure of central tendency, the mean. The

strategy of permuting the combinations is analogous to the strategy behind the

MRI, which takes many ‘pictures’ of the same tissue from different angles, and

then produces a better, composite, through subsequent computer recreation of

the tissue from the different pictures, at different angles [13]. The objective

of Mind Genomics is to determine how the respondent weights the different

elements to arrive at a decision. Thus, the vignettes are only vehicles to

embed the elements, and to present these elements in a way which forces the

respondent to assign a ‘gut feeling response’ to the combination. The creation

of 24 combinations prevents the respondent from assigning the ‘politically

correct answer’ or from ‘gaming the system’. Indeed,

often the comment from a respondent is of the order of ‘I could not figure out

what the right answer was…so I guessed’. Step 3: Steps at the Start of the Start of the Evaluation The

respondents are invited to participated by an email. The on-line panel

provider, Luc.id Inc., maintains groups of respondents around the world in more

than 40 countries. The respondents have already agreed to participate, and are

accustomed to doing surveys. Whereas in previous years, at least until the

advent of the Internet, respondents could be found who had NOT participated

during the three months prior to the study, today’s world comprises very few of

these ‘naïve’ panelists, without experience. Although the respondents from

Luc.id can be said to be ‘experienced’, they reflect the typical respondents

available today, consumers, not experts. At the beginning of the interview the

respondent provided information about age, gender and answer a third

classification question. How do you feel about insurance companies? 1=I trust

them, 2=I have to watch them, 3=I don't trust them, 4=Not applicable. Step 4: Evaluation

of Vignettes The

respondent read the following instructions: Here is the description of a

situation about a contractor and insurance. How would you feel about this

situation if this were you? · Definitely avoid

this · Move forward

slowly with trepidation · Move forward

quickly with trepidation · Move forward

quickly · No hesitation The

respondents then read each of the 24 vignettes, doing so fairly quickly

(generally less than 5-6 seconds for each vignette). In general, Mind Genomics

studies are executed fairly quickly on the Internet, especially when the topic

is simple. The entire study lasted about 3-4 minutes for each respondent. The

respondents are not deeply interested in the topic, and there is no way for the

researcher to subtly influence the respondent regarding either the seriousness

of the topic or the expected ‘right answer.’ Thus, the answers represent the

intuitive best guess from the respondents, who are both uncertain about what is

correct, but motivated to finish the study with some sense of honesty because

they belong to a panel of respondents who do many studies. Step 5:

Transformation of the Ratings Managers

prefer simple information, such as ‘yes/no’ rather than scalar information. Indeed,

the scalar information, while capturing nuances of feeling, is hard to

understand. When managers are presented with the results, average ratings on a

5-point scale, for example, often the first question is not about the data

themselves in terms of the answers to questions, but rather the more basic

question ‘what does a 3 mean?’, and so forth. In

light of this apparent uncertainty in the interpretation of questions, consumer

researchers as well as political pollsters have opted to present their data in

binary terms when talking to the public, although they use the metric or scalar

data for many of their statistical

computations

in the background, for other purposes. In the spirit of this effort to make the

data simpler to understand we transform the ratings to a binary scale. Ratings

of 1-3 are recoded to ‘0’; ratings of 4-5 are recoded to ‘100’. To each recoded

response we add a very small random number (<10-5), in order to add small

but necessary variation to the ratings, for subsequent analyses by OLS (Ordinary

Least-Squares Regression). Step 6: Mind-Set

Segmentation The

objective here is to move beyond conventional division of people into age,

gender, and even attitude towards insurance companies. Rather, the objective is

to divide people by how they respond to messages about a micro-topic, in this

case the insurance to be purchase by the homeowner for contractor failure. There

would be no other way to divide people by mind-sets, other than ‘doing the Mind Genomics

experiment

and dividing the respondents based on the data from that specific experiment’. The

process is straightforward. The data allow us to generate an Generate

individual-level model (equation) for each respondent, relating the

presence/absence of the 16 elements to the binary transformed ratings for that

individual respondent, and then cluster (segment) the respondents into two and

three groups (mind-sets) based upon the pattern of the 16 coefficients for each

respondent. Recall that the 24 vignettes for each respondent were created by an

underlying

experimental design.

That designed produced 24 unique vignettes, unlike the 24 vignettes for any

other respondent. Each respondent thus generates a set of 24 rows of data, with

the first 16 columns of data being the 16 elements, with the cells having

either a 0 when the element is absent from the particular vignette, and present

when the element is present in the vignette. The 17th column is the

binary transformed rating. The

data for each respondent are subject to OLS (ordinary least-squares)

regression. The independent variables are the 16 elements, the dependent

variable is the binary rating. The result equation, calculated at the

respondent level is: Binary Transform=k0 + k1(A1) + k2(A2)

… k16(D4). The data matrix now comprises 100 rows of coefficients

k1…k16. The additive constant is ignored. The coefficients give a sense of the

driving value of the element towards rating 4-5 (4=move forward quickly; 5=no

hesitation). The respondents are clustered using k-means clustering [14]. The

respondents are objects to be put together in homogeneous groups, based upon

the pattern of coefficients. The criterion is the quantity (1-Pearson

Correlation (R)). The quantity (1-R) takes on the value 0 when two respondents

show a perfectly linear correlation of +1, based on their 16 coefficients,

meaning that they virtually identical in the criteria of judgment. They belong

in the same cluster or mind-set. Two people belong in different mind-sets when

the quantity (1-R) takes on the value 2, which occurs when the coefficients of

the two respondents move in precisely opposite directions. These two

respondents belong in different clusters, or mind-sets. Step 7: Create

‘GRAND’ Models (Equations) for Each Key Subgroup, Relating the Presence/Absence

of Elements to the Transformed Rating The

model is expressed in the same format as the model for the individual

respondent, except that the model is created using ALL the data from a

particular group (age, gender, mind-set, and opinion of contractors). The

equation once again is: Binary Transform=k0 + k1(A1) + k2(A2)

… k16(D4). Step 8: Create

Models (Equations) for Response Time, for Each Subgroup The

Mind Genomics program measures the response time, defined as the number of

seconds (to the nearest 10th of a second) between the time that the

vignette was presented to the respondent, and the time that the respondent

assigned a rating. Some of that time was taken up by the actual time to push

the correct key, but that time is impossible to estimate. The OLS regression

(estimated without the additive constant), apportions the response time to the

different elements in the vignette. The rationale for not estimating the

additive constant is that in the absence of elements, the estimated response

time is 0. In contrast, for the rating, the additive constant is estimated

because in the absence of elements, the additive constant shows the proclivity

to be positive to contractor insurance. The model for response time (in

seconds) is expressed as: Response Time=k1(A1) + k2(A2) …

k16(D4). We

present the results from the study, looking only at the positive coefficients

for the transformed rating scale. These are the elements and the key subgroups

where the element drives to a rating of YES, operationally defined as a rating

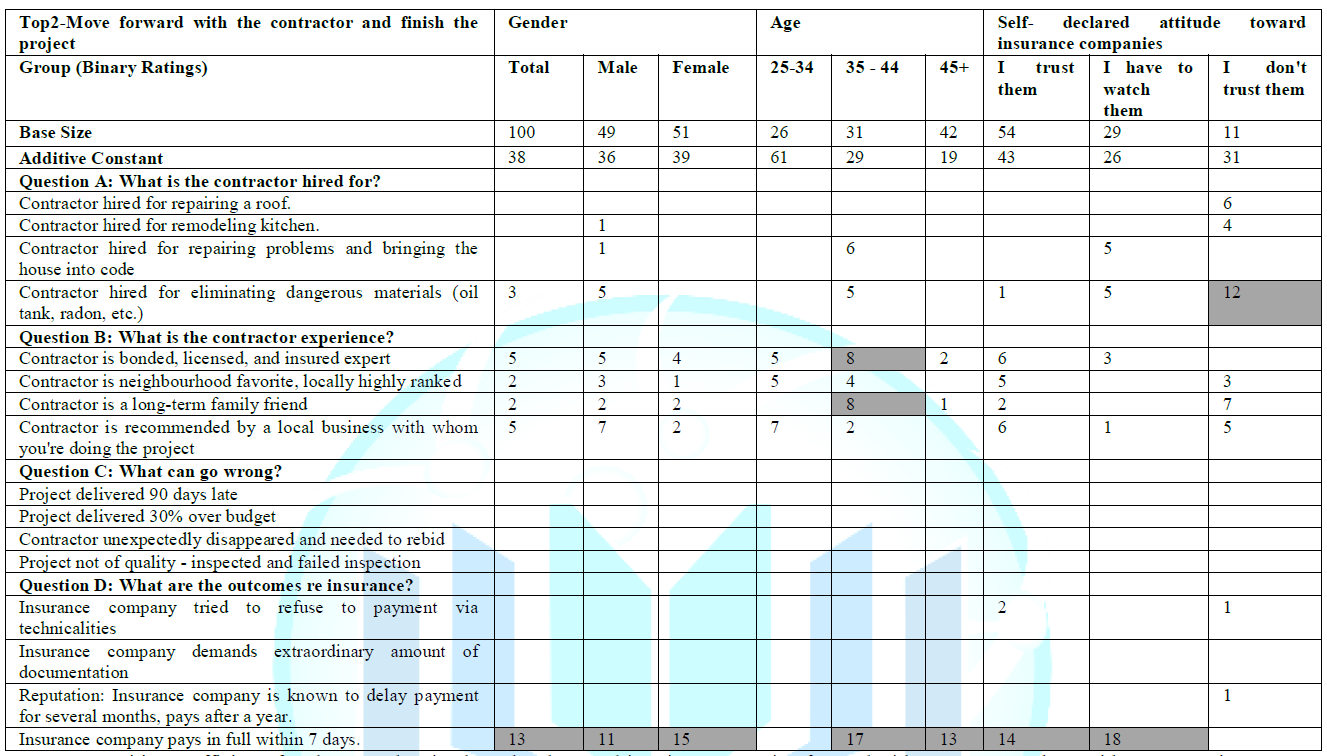

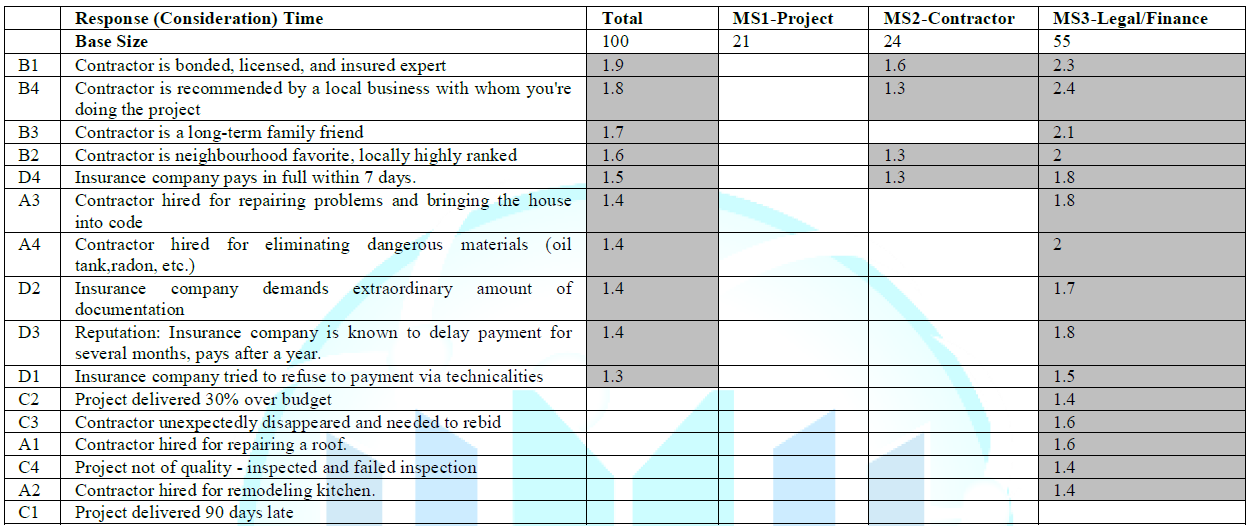

of 4 or 5, previously transformed to 100. Table

2 presents the positive, non-zero elements for total panel, for gender, age

and for three of the four self-declared attitudes about insurance companies.

The fourth answer, not applicable, had only 6 respondents. The negative and 0

coefficients are not shown because they either represent a desire NOT to move

forward and complete the project, or indifference. We will look at the drivers

of desire NOT to move forward below, in Table

4. The additive constant gives a sense of the desire to move forward, to

finish the project. The additive constant is low for gender (36 for males, 30

for females), suggesting a basic disinterest in moving forward. The low

additive constant comes from those age 35-44 and 45+. The older respondents

truly not want to finish the project, whereas the younger respondents do want

to finish the project. Surprising, those age 25-35 show the most interest in

moving forward, to finish the project. Finally,

as expected, those with a self-declared negative attitude towards insurance

companies show a low additive constant, a low desire to move forward and finish

the project. The elements themselves do not drive the respondents to say that

they would like to finish the project. The only elements which really drive

interest in the combination of contractor and

insurance

are WHO the contractor IS. Viz., D4: Insurance Company pays in full within 7

days. Table 2: Positive coefficients for elements showing how the element drives interest moving forward with a contractor, along with contractor insurance. Table 4:Strong-performing coefficients for elements, showing how the element drives interest in STOPPING THE PROJECT The data shows the strong coefficients

emerging from a ‘bottom-up analysis’ where the positive coefficients mean stop

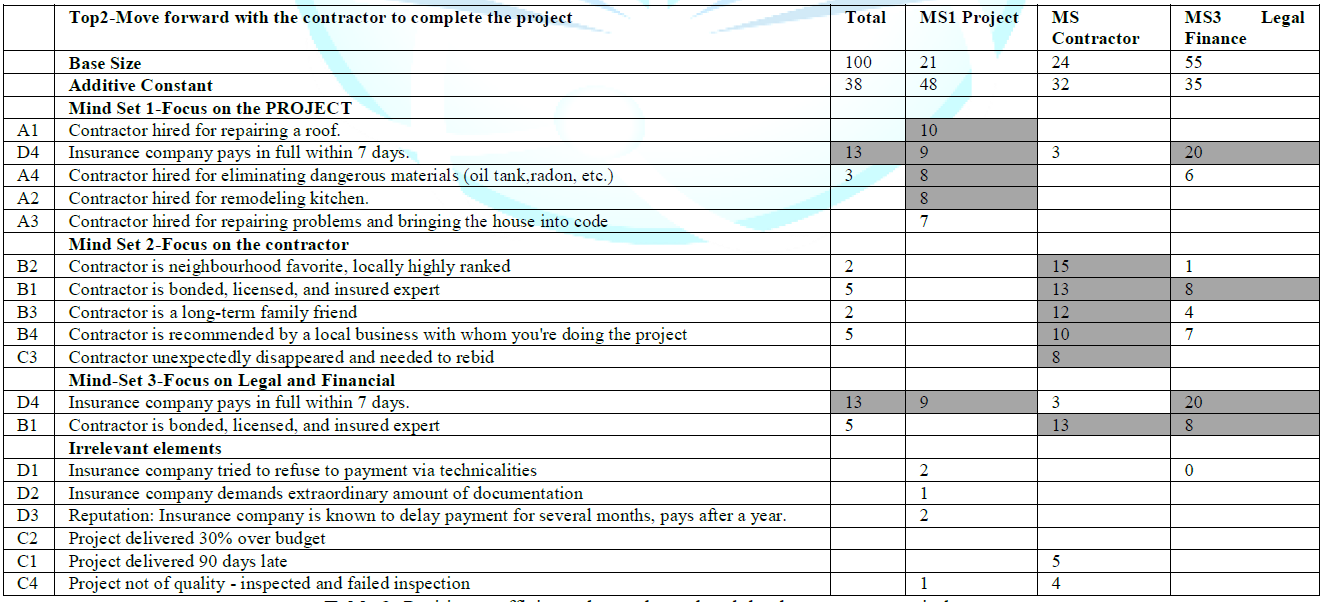

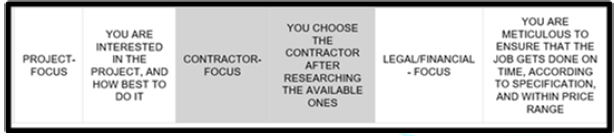

the Project. Only elements strong in at least one subgroup are shown. Mind-sets

emerging from the pattern of pattern of responses show a radically different

pattern (see Table 3). Three

mind-sets emerged, two of which are small (MS1 focusing on project; MS2

focusing on the contractor). The third mind-set (focusing on legal and

financial aspects of the job and the contractor relationship constitutes more

than half of the respondents, 55 out of 110. The mind-sets show dramatically

stronger performing elements, which is to be expected since the mind-sets reflect

groups of respondents who think quite differently from each other, based upon

the pattern of their coefficients. The mind-sets differ dramatically in their

basic interest in moving forward, with those respondents in Mind-Set 1 (Project

focused) showing the highest level of interest in moving forward (additive

constant=48). The other two mind-sets, Mind-Set 2 (Contractor focused) and

Mind-Set 3 (Legal/Financial focused) show lowest levels of interest in moving

forward (additive constants 32 and 35, respectively). It

is in the specific elements where we see the big differences, both in the

nature of the elements with drive ‘moving forward’, and in the magnitude of

those strong-performing elements. Those interested in moving forward, beginning

with the highest basic interest (additive constant=48) are all significantly

positive to the messages about the project, with coefficients between 8 and 10.

In contrast, it is Mind-Set 2, focus on the contractor, the ‘personal link’

which drive the strongest positive response for moving forward. The

coefficients are 8-15, suggest the strong effect of emotions. Finally, those in

Mind-Set 3 (Legal/Finance) react most strongly to the legal and financial

aspects. When

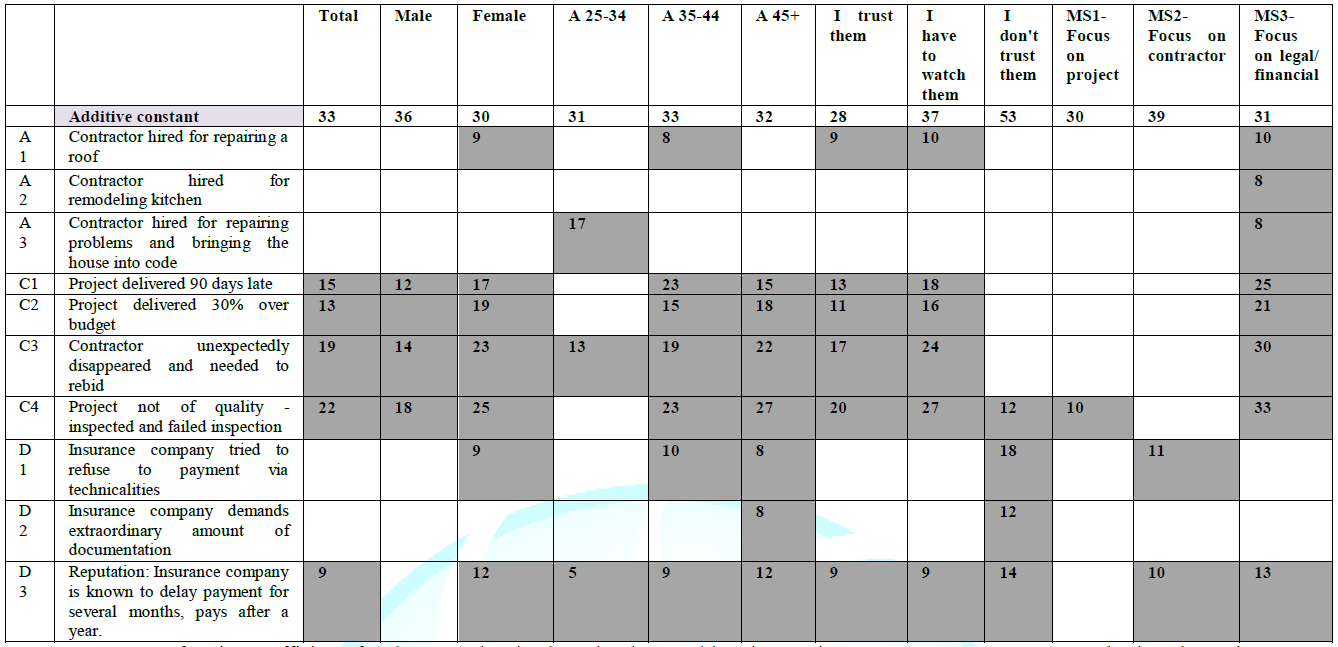

‘things go wrong’ we get a different picture. Table 4 shows the set of

coefficients we do the reverse analysis, looking for the elements which drive

the respondent to say ‘stop’. The analysis begins with a different recoding.

The ratings at the low end of the scale, 1 and 2, are converted to 100, and the

ratings of 3,4 and 5 are converted to. A small random number is added, and then

the equations are recalculated. The additive constant shows the basic

likelihood of ‘stopping’ without any elements. The coefficient of each element

shows how strong it is as a message to stop the process. We show only the

additive constant and the strong-performing elements. The coefficients are

those corresponding to elements which ‘stop the process’. The

additive constant, the proclivity to stop the process, is low except for those

respondents who, at the start of the experiment, before the actual evaluation,

declare that they do not trust insurance compaiess. Their additive constant is

53, 14 points higher than the next highest group (Mind-Set 2, focusing on the

contractor). There are two classes of elements which drive to ‘stop’. The first

is the nature of the project, with roof repairs being the least trusted, then

the contractor hired to bring the house into code, and then finally the

contractor hired for remodeling the kitchen. The roof contractor is really the

one least trusted. The second group of elements, which should come as no

surprise, is the failure of the contractor to deliver what has been agreed to.

Surprising, the youngest respondents, age 25-34, are the least likely to

respond that they want to stop the project. Response

(Consideration) Time-Making a Decision The

foregoing analyses of responses focus on the conscious evaluation of the different

vignettes. As the data suggests, the results lend themselves to straightforward

interpretation. Even though the speed of the experiment was such that

respondents appear to have rushed through the study, as they were meant to, the

conscious responses suggested that the respondents were actually paying

attention, even though in many of these studies respondents aver quite

vehemently that they were confused, and were simply guessing. That ‘guessing’

certainly does not appear to generate random data. At

a deeper level, however, one can study the response time, the time it takes to

read a vignette and rate it. Of course, the time to rate each vignette does not

tell us much, just as the rating of a single vignette does not tell us much.

Yet, we can use OLS regression to deconstruct the response time into the number

of seconds estimated for a person to ‘mentally process’ each element. There

will, of course, be some slack time needed to read and to rate, but this will

be divided among the individual response times for the elements, those times

estimate by OLS regression. The analysis proceeds as before, using as input ALL

the data from a particular subgroup (e.g., age, gender, answer to

classification question about contractors, mind-sets). We focus here only on

the four models, specifically total panel, and the three mind-sets (see Table 5). The response time model is: RT

= k1(A1) + k2(A2) … k16(D4). The response time

model is expressed in the same way as the binary, except for the absence of the

additive constant. The ingoing assumption is that in the absence of elements

the response time is 0. The response time is measured to the nearest tenth of

second. The coefficients are also presented to the nearest tenth of second,

viz., at the level of resolution of the measurement itself, rather than greater

resolution (viz., not to the hundredth of a second). Table 5 shows only those

response times exceeding 1.3 seconds for the element. There are quite a number

of these long response times, especially for Mind-Set 3, focusing on the

legal/finance issues, individuals who would be expected to pay attention to the

so-called ‘fine print’. Those in Mind-Set 2, paying attention to the

contractor, focus on descriptions of the contractor. Those in Mind-Set 1,

focusing on the project itself, do not pay deep attention to any of the

elements, but rather read them quickly. It is clear that one element needs no

thought for driving a judgment, element C1, Project delivered 90 days late. It

is clear from the elements of response time, considered in the area of

financial topics, that response time or consideration time presents to the

researcher an entirely new opportunity to understand the nature of how people

think and make decisions in topic areas that are commercial, serious, service-related

rather than product related. Discovering the

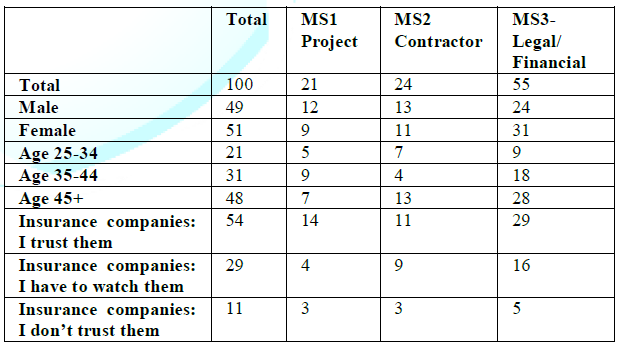

Mind-Sets in the Population During

the past sixty years consumer researchers have suggested that the purveyor of

products and services might do well by segmenting or dividing the prospects,

either by WHO the prospects are (geo-demographics), by hat the prospects

BELIEVE (psychographics) or by what the prospects DO (behavior). All three

forms of dividing people have their adherents, and their detractors. All three

methods, and the dozens of specific procedures in each general method, begin

with a general division of the prospective consumers into easy-to-develop

groups. Once these groups are created, it is the task of the marketer to know

what to say. This

study, building from the ‘bottom up’, with the specifics and thus granularity

of the topic, suggests a problem with conventional segmentation. The problem is

that the three mind-sets, specific to the topic, divide across conventional

groupings of people, as Table 6 shows. The three mind-sets show similar

distributions in WHO the person is (gender, age) and what the person BELIEVES

(Answer given at the beginning of the study, in the self-classification

portion). One would never guess from Table

6 that the three mind-sets could be so different. These mind-sets comprise

the same type of people, at least from the outside. Rather

than assuming that people who look similar to each other in terms of gender,

age, or even attitude toward contractors will be similar in the way they

respond to the messages about contractor insurance, a more sensible way might

be to create a small intervention, a set of easy-to-answer questions, the

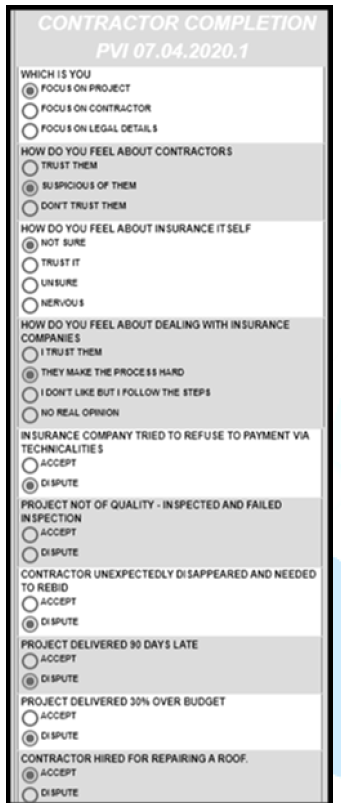

pattern of responses to which assign a person tone of the three mind-sets. When

this set of questions, the so-called PVI (personal

viewpoint identifier),

is deployed the knowledge about the mind-set membership allows the insurance

salesperson to select the right insurance package for the prospect. The

interaction becomes more personalized, simply because the insurance salesperson

now knows the ‘insurance-relevant’ mind of the prospect, in a way which is

granular. Table 6: The division of

respondents into WHO the person is (gender, age), and what the person believes

with respect to insurance companies). Recently,

author Moskowitz and colleague, Professor Attila Gere, have developed a PVI,

based upon the pattern responses to the elements, and using Monte-Carlo

simulation to identify the best set of relevant elements to use as the six

questions. The PVI enjoys a strong advantage over other methods because the raw

material used to create the PVI is identical to the raw material used to define

the mind-sets. For the PVI presented here, the specific computations were made

from the data summarized in Table 4, showing how each element corresponded to

stopping the project. The tenor of the low side of the scale, stopping the

project, made more sense. Figure 1

shows the PVI for one respondent. The actual link as of this writing (Summer

2020), can be found at https://www.pvi360.com/TypingToolPage.aspx-?projectid=196&userid=2018. Figure 2 shows the feedback for one

respondent. The mind-set to which a respondent is assigned appears as shaded

boxes box. The other two mind-sets appear as unshaded boxes. Figure 1: The viewpoint

identifier. Figure 2: The feedback

given to the respondent regarding mind-set membership. The

experiment reported here on regarding the specific messages which drive a

prospective customer to purchase insurance covering home repair jobs represents

an intermediate step between the insurance company which designs and sells the

insurance, and the prospective customer who needs to be convinced. As noted

above, much if not a significant proportion of information about what it takes

to convince the prospect to buy comes from the marketing and marketing research

departments of insurance companies. The academic literature focuses on the

patterns of purchase, who purchases, why they purchase, and the financial

aspects of the insurance itself. There are a lot of insurance companies in the

world, and, in turn, a great deal of advertising, advertising testing, and an

entire world of professional

consumer researchers

supporting the effort to sell the advertising. Tools such as focus groups

produce insight into what insurance prospects need, and the language that the

insurance prospects, the customers, actually use to express their need. Following

the early research efforts comes concept tests, and limited roll outs of

insurance plans, combining the insurance company, agents, advertising agencies,

and media specialists. Mind

Genomics occupies a unique position in this mix of expertise, and the mix of

different groups. Mind Genomics is an experiment, through which one can

understand the specific, granular preferences of prospects in a particular

domain, such as home project insurance. What is important to note is that the

Mind Genomics effort is to understand the minds of people from the ‘ground up’,

for a specific topic (project insurance) rather than to look at the topic from

the perspective of theory (e.g., Theory of Reasoned Behavior), or from the

perspective of commerce (viz., ‘what works’ in advertising messaging). The

‘larger project’ of Mind Genomics is to assemble the results these studies, and

from that assemblage, formulate grounded hypotheses about how the person weighs

information and makes decision in the world of commercially-relevant topics. Attila

Gere thanks the support of Premium Postdoctoral Research Program of the

Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Howard Moskowitz, MindCart AI, Inc., White Plains,

New York, USA, E-mail: mjihrm@gmail.com

Moskowitz H

and Gere H. Selling to the mind of the insurance prospect: A mind genomics

cartography of insurance for home project contracts (2020) Edelweiss Psyi

OpenAccess 4: 22-28. Mind genomics, Cartography, InsuranceSelling to the ‘Mind’ of the Insurance Prospect: A Mind Genomics Cartography of Insurance for Home Project Contracts

Abstract

Full-Text

Background

Results

Discussion and

Conclusions

Acknowledgment

References

Citation

Keywords