Introduction

In

a woman’s life after marriage child birth is the most significant event.

Particularly the first child birth is associated with lot of anxiety,

excitement, fear, happiness and a sense of fulfillment. It is increasingly

being recognized that the mind exerts a powerful effect on the body resulting

in many psychosomatic disorders like hypertension, diabetes etc. Child

birth is intimately connected with the health of the mother and the child.

It is rather unfortunate that in many developing countries the conditions of

delivery are not very satisfactory particularly in rural areas. Madhya Pradesh,

a state in India has a population of about 70 million. Here only 40% women are

literate (based on Census of 2011).

This

leads to lack of awareness of health problems and sticking to the traditional

methods of delivery which are usually not very safe. Besides there are many

social customs associated with pregnancy, child birth and feeding of the child.

They can also affect the health of the mother and the child. All these factors

differ from region to region and from community to community. With these facts

in mind a study was conducted in Birla Nagar ESIS (Employees State Insurance

Scheme) dispensary to analyze these health factors and their probable outcome on

health of the mother and child. This locality is mainly inhabited by workers of

different factories of Gwalior town who are mainly of low socio-economic

status.

Review of Literature

Park

et al, conducted a study in Dabra in Gwalior and found 21.5% low birth rate in

1051 cases of delivery. Park et al, conducted a similar study in Gwalior on

2927 deliveries and found low birth rate in 18.6% cases. It was 16.6% in males

and 20.7% in females. Balfour found

It

was based on the concept that the vulnerability of illness results from number

of interacting biological factors such as genetics, environment, psychosocial status

etc that can be measured as expression of probability of future need for care.

The Risk Approach uses these estimates to know a woman’s need for help and

guidance. However it is a fact that maternal deaths are not avoidable by

traditional preventable health care. In order to save maternal deaths good

quality of obstetric services must be available particularly in emergencies.

Majority of deliveries in Central India, particularly in rural areas continue

to take place at home under traditional settings which are not very hygienic.

In such a situation first referral unit can offer little and facility should be

available to reach proper care center at reasonable time. About 75% maternal

deaths occur in the last trimester and the first week following the end of

pregnancy [12-14].

There

are various population based approaches for estimating the obstetric risk such

as

i-Vital Registration: It is widely

available source of information on maternal death. In many developing countries

the coverage of registration is poor and the cause of the maternal death is not

mentioned. Even from some developed countries like UK, USA and Latin America

maternal deaths are not properly recorded [15-24].

ii-Vital

Registration with interview: This approach is particularly suitable where the

registration is fairly complete but scientific information on cause of death is

not available. This approach has been tried with some success in USA,

Bangladesh, Egypt, MOH and UK. However, in developing countries this method was

not found very useful [25-29].

iii-Sisterhood Approach: This is an

indirect approach to circumvent the problem of large sample size needed to

collect the data [30].

iv-Networking

Approach:

In this the respondents are asked to identify ant maternal death of which they

are aware [31].

Then there are model based approaches of estimating obstetric risk. It was first used by WHO in 85 countries [32]. Drvraj et al, [33] Ranjan [34] and Borema [35] also developed modes. Blum and Fargues [36] used existing life tables to estimate maternal mortality. Ranganathan and Rode [37] Fathalla [38] and Thaddeus and Maine have also described different methods [39,40]. Madhya Pradesh is a part of central India where obstetric care is quite poor. A survey was carried out in Madhya Pradesh in 2003 which covered 25% of rural population. It was found that 763 deaths occurred in 2003 for every 100,000 live births (Govt of Madhya Pradesh). It was much higher than the incidence in urban areas [41]. Rao et al, conducted a survey on protein malnutrition in poorer sections of the society [42]. They found that 92% infants were breast fed for 6 months after which supplementary food was added. Onset of pregnancy was the main cause of weaning. Belavady et al, studied breast feeding in tribal areas of South India and found that breast feeding was up to about 12 months probably as they did not have any supplementary food to add [43]. Gopalan found that they used garlic, tamarind and cotton seed as they believe them to be lactogogues [44]. Mahadevan in a similarly found that longer the breast feed longer would be life [45,46]. Pasricha in a diet survey of 70 lactating women found an average intake of 1860 calories with a mean intake of 40gm protein, 300mg calcium and 25mg iron. Karmarkar et al, in a similar found intake of 1400 calories, 40gm protein and 30gm fat, Calcium was 300 mg and iron was 30 mg [47,48]. Wicks and Davidson found that the incidence of breast feeding was falling in higher societies [49,50]. Newton NR and Newton M observed that in breast feeding mother’s attitude was important. Mathews and Platt also found prolonged breast feeding in low socio-economic groups. Ahluwalia observed that in some communities delivery was conducted in squatting position of the mother. He also found that in some cases some type of shock was given to the mothers if the delivery was getting prolonged. In postnatal period visitors were restricted up to 40 days [51-55]

Material and Methods

The

ESIS dispensary is situated in Birla Nagar area of Gwalior town in India. There

are three big factories nearby including JC Mills, CIMMCO and Steel Foundry.

All workers in these factories go to the above dispensary for all types of

treatment. The serious or complicated cases are referred to specialty

departments of the local medical college hospital. All family members of the

workers are also treated here. The study was conducted mainly on a detailed

history taken according to a questionnaire proforma

prepared for the study. Although a large number of women and their relatives

were interviewed but because of poor level of literacy and knowledge complete

answers could be taken from only 250 cases after repeated interviews. In many

cases the answers too many queries had to be obtained from the mother-in-laws

of the women or from their other relatives. Many women were found to be very

reluctant in disclosing their personal matters and had to be persuaded with

great difficulty. Data thus obtained was recorded in 21 tables and was analyzed

in this study.

Discussion

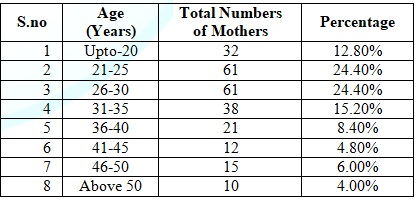

As

regards the age of the mothers 50% mothers were in the age group of 21-30

years. There was no difference between the age groups of 21- 25 and 26-30 years

(Table 1). Park et al, also found

maximum incidence in 21-30 yrs [4]. Age group (56.6%) In his subsequent study

at Gwalior he found the incidence a little higher (61.6%). In his both studies

women below the age of 20 years were 21% whereas in our study it was only 12.8%

[5]. In low socio-economic families it is a general trend to marry girls at a

fairly early age. A married girl is considered much safer that an unmarried

young girl. However with growing education in women this trend is gradually

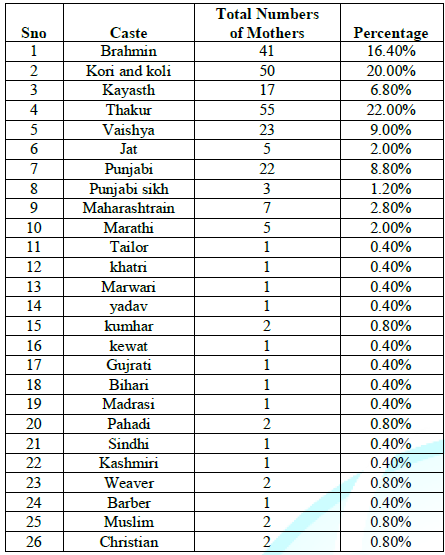

declining. Earlier the society was strictly divided into four casts viz.

Brahmin (learned class), Kshatri (warrior class), Vaishya (trader class) and Shudra

(labour class). Marriages were done mainly within one’s own caste. However from

last about 70 years there has been a considerable case of inter caste marriages.

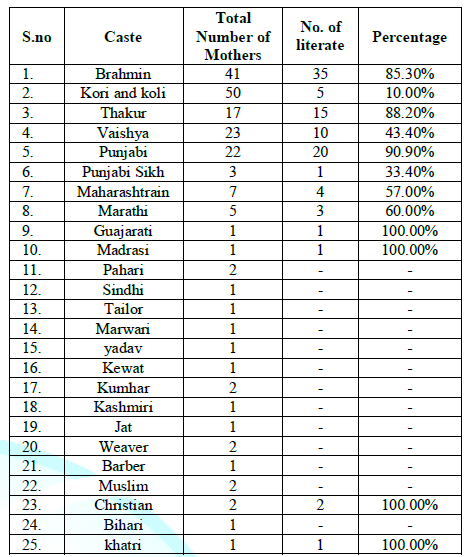

Hence from Table 2 showing the caste

no definite indication could be made out. It may be said that the upper

(Brahmins and Kshatriyas) and lower classes (Vaishyas and Shudras) are nearly

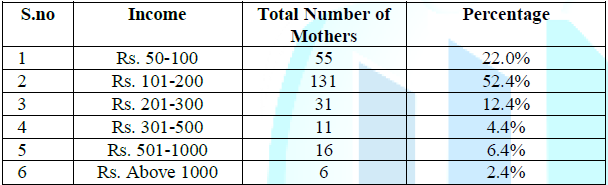

equal. In Table 3 the husband’s

income is certainly very low affecting the welfare of pregnant women and the

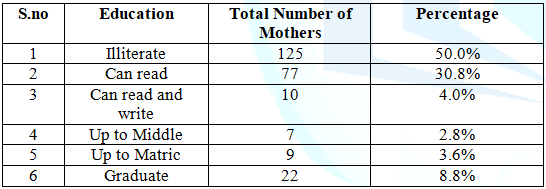

new born child. As shown in Table 4a

50% of women were totally illiterate and another 30.8% could only read local

language.

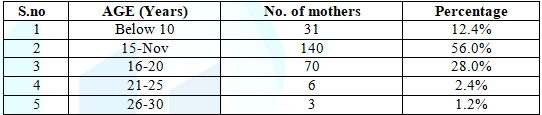

Table 1: Distribution of mothers by age.

Only

8.8% women were graduate. Misra [56] in her extensive study on education of

women in India observed that in 1965-1966 in primary education (class 1-5)

there were there were 30.12 million boys and the number of girls was only 19.52

million. If the figures for low socio-economic group are considered the difference

would be still more [57]. Due to lack of education there was very little health

awareness including maternity problems and the women were mainly guided by age

old traditions which were not very hygienic. All these factors led to high maternal

morbidity and high maternal mortality rate. Park in his study at Dabra found 21.5%

and at Gwalior 18.6%. Table 4b shows

the literacy level caste wise [4,5]. The maternal mortality is much higher than

in Western countries [15-17,20,35]. Table

5 shows the mother’s age at the time of marriage. It is alarming that 31

mothers (12.4%) got married below the age of ten years.

Table 2: Distribution of mothers by caste.

Table 3: Husband’s

income.

Table 4a: Education of

Mother.

Another 140 (56.0%) got married between 11 and 15 years whereas the law of that

land states that marriage below 18 years is illegal. It also reflects the

callousness of local authorities to take proper action. This is an alarming

situation. In poorer people it is the belief that the girls are safer after

marriage and hence marry them at the earliest. The state authorities have also

been not very strict unfortunately. However the trend is changing with

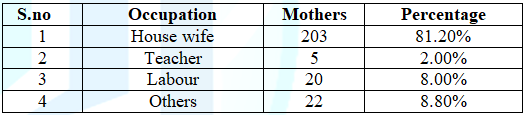

education and awareness. Table 6

shows the distribution of mothers by occupation. With very low level of

literacy and early marriages 81% of women were simply house wives without doing

any other kind of work to supplement income of the family. Only 2% were

employed as teachers and the rest were either laborers or doing odd domestic

jobs. Park in his two studies found only 16% primipara [4,5]. Thus with more

number of children it becomes difficult for a mother to do even a part time job.

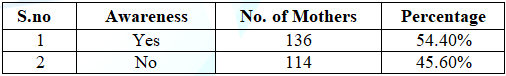

Only 54.4% mothers had some awareness about antenatal care. The rest had no

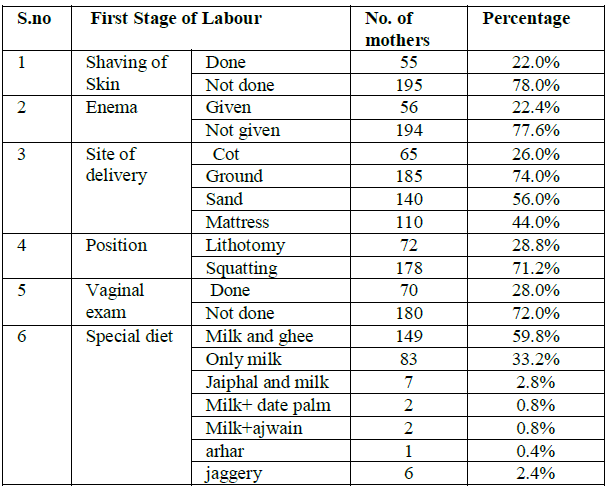

knowledge about it Table 7. In Table 8 practices regarding the first

stage of labor are shown. Shaving of the skin and enema was not given in 78%

cases. Ground delivery was much preferred (74%) than cot delivery (26%). Sand

was

Table 4b: Literacy status by caste.

Table 5: Age of Mother at Marriage

Table 6: Distribution of mothers by occupation.

Table 7: Awareness of Antenatal Care of Mother.

more

preferred than mattress as it would absorb blood, maternal discharge etc.

Squatting position was preferred (71.2%) than lithotomy position (28.8%) as it

might help delivery by gravity. Vaginal examination was usually not done. In

diet, milk, ghee liquefied butter, date palm and jaggery was preferred. In the

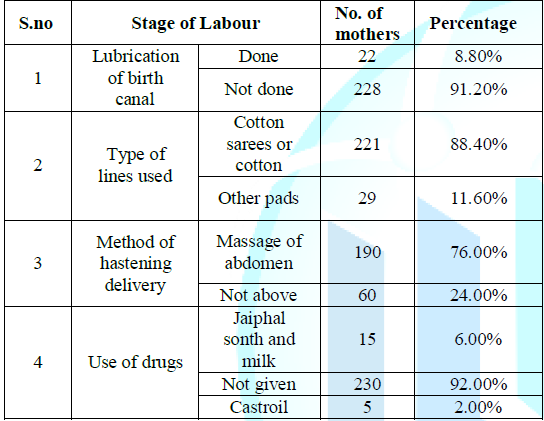

second stage of labour (Table 9)

lubrication of birth canal was done. Cotton sarees were mainly used. For

hastening the delivery massage of abdomen was done in about three fourth cases

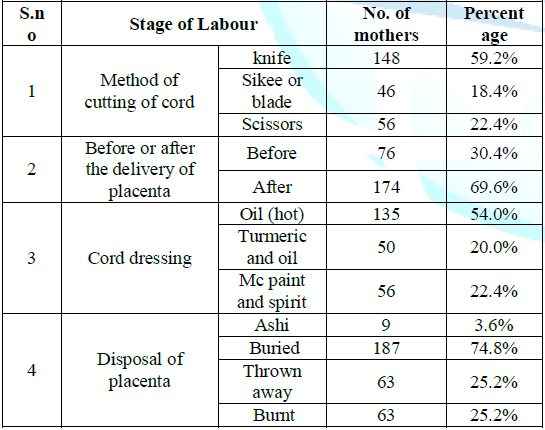

(76%). No drug or food was usually given in second stage. In the third Stage Table 10 knife was usually used for

cutting the cord (59.2%). Blade or scissors were also used in some cases. Cord

dressing was done mainly by hot oil (54%) or turmeric with hot oil

(20%).Placenta was usually buried (74.8%) but in some cases it was thrown away.

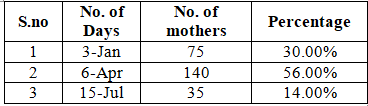

Table 11 shows the duration of lying

period in the initial post-natal period Majority of mothers kept lying from 4

to 6 days (56.0%). 30.0% were lying for 2-3 days. 4% took bed rest. Some

patients however took rest from (7-15 days) Usually after first delivery

mothers take lesser time in subsequent deliveries. However, this was not found

in the present study. Table12 shows

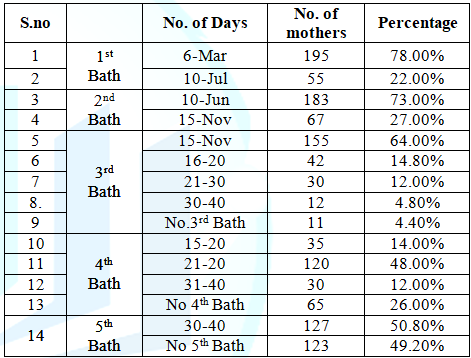

the post-natal bath habits.78% took first bath between 3rd and 6th days (78%)

and 22% between 7th and 10th day. The second bath was mainly taken between 7th

and 10th day. The time for 3rd bath was variable. Timing of bath also depends

on season.

Table 8: First Stage of Labour.

Table 9: Second Stage of Labour.

Table 10: Third Stage of Labour.

Table 11: Post-natal Period-I Lying Period.

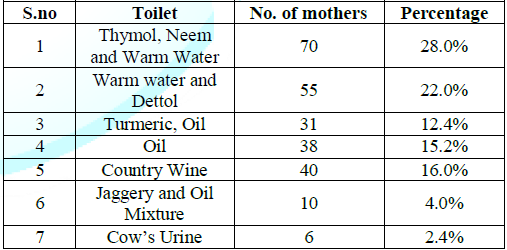

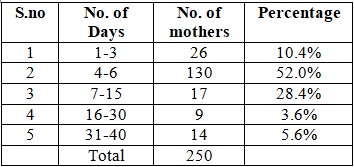

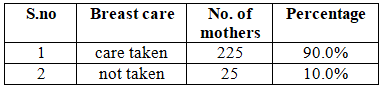

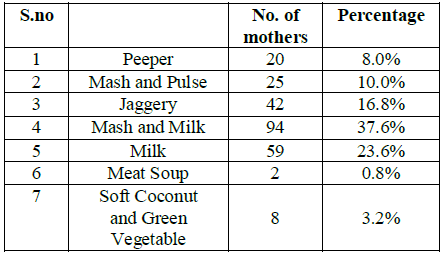

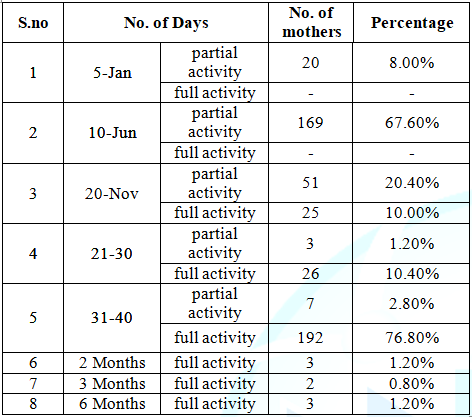

Table 13 shows the practice of perineal toilet. Neem or Ajwain in warm water was the commonest method (28.0%). Warm water with dettol was also common (22.0%). Neem is a well-known antiseptic and was also used with warm water. Table 14 shows the time after delivery when visitors are allowed. It is necessary to avoid infection to the mother and the new born. In majority of cases visitors were allowed between 4-6 days (52%). In 28.4% they were allowed between 7 to 15 days. It is not only the time but the type of visitors and precautions taken by them. They are supposed to put off their shoes and the child is not allowed to be touched without washing hands. With the advent of potent antibiotics people have become slightly slack in observing these precautions Table 15 deals with breast care and methods by which secretion of mother’s milk can be increased. In this about 90% of mothers knew much about breast care. Jaggery, pulse, meat soup and green vegetables were given. Pasricha and Karmarkar in similar study observed that Indian women in spite of inadequate diet were able to produce a fair quantity of milk for a long time. Wicks, Davidson and Newton had similar findings. Jaffe, Mthews and Platt found that prolonged feeding was because they did not have any supplementary diet to offer [47-54]. Table 16 shows resumption of work during post-natal period. 67.6% women returned to partial work after a week. 20.4 mothers returned to work after 2-3 weeks almost three fourth returned to full work after a month’s time. However, there are other factors also which can influence this period such as age, health of mother etc. Hence there is no rule of thumb.

Table 12: Post-natal Period-II.

Table 13: Post-natal Period-III Perineal Toilet.

Table 14: Post-natal Period-IV Visitors.

Table 15: Post-natal Period-V Breast Care and Lactogogues.

Table 16: Post-natal Period-VI Visitors.

Table 18: Care of new born-III Clothing.

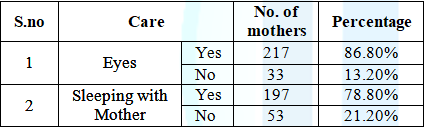

Table 17 shows some

aspects of the care of the new born. 80% of mother slept with their child to

take care during the night time. Many of them were of the eye complications

also and consulted accordingly. In the day time relatives were available to

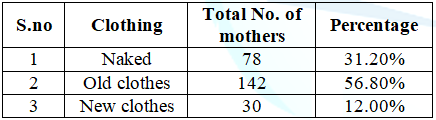

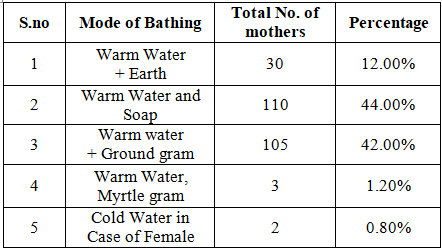

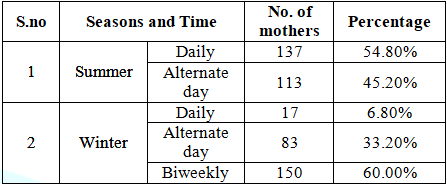

take care. Table 18-20 shows about

the bath and of clothing of the new born and the mother. 56.8% used old clothes

of the relatives as they considered softer that the new ones. Nearly one third

children remained naked. Mostly warm water and soap was used for bathing. 54.8%

mothers took daily bath in summers but only 6.8% in winters. In winters most

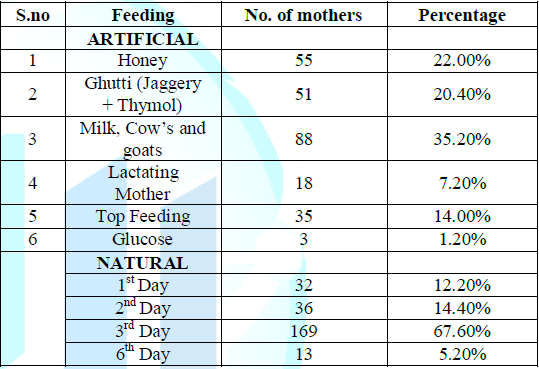

mothers took bath twice a week. Table 21

shows about the feeding pattern. Breast feeding was started from the first day

by only 12 mothers (12.2%). 36 mothers (14.4%) started from the second day

while 169 (67.6%) from the third day. In most cases it was supplemented by

cow’s or goat’s milk. 18 mothers (7.2%) resorted to the help of other lactating

mothers. Rarely glucose was given.

Conclusions

A study was undertaken to know about various social customs and practices associated with pregnancy, child bearing and child rearing in 250 women in the industrial area of Gwalior city of India. They were mainly from three factories via JC Mills, Gwalior Rayon and

Table 19: Care of new born-IV Bathing.

Table 20: Care of new born-IV Bathing B.

.

Table 21: Care of new born-V Feeding.

CIMMCO

factory. All of them are situated in the Birla Nagar locality of Gwalior city. All

workers in these factories came to ESIS (Employees State Insurance Scheme)

hospital for their treatment as well as treatment of their family members Study

was conducted on the women of the employees and various details about the

social customs in vogue during pregnancy,

child birth and after care of these child and the mother. In these matters many

family traditions are usually followed and many of them are not very hygienic

and are due lack of education and awareness.

Hence

health education is very important in these cases which was also done along

with the study. Ahluwalia [55] has rightly observed that that women in low

socio-economic strata are very reluctant to give the traditional methods of

conducting delivery and refrain from unhygienic practices. Misra in her

extensive study on women education in India and MP State (Gwalior is in MP State)

has mentioned that lack of education is the main cause of many health problems

in women including child birth. Traditions die hard. Hence many women and their

relatives often resist many hygienic practices which are advised. It is

therefore better to win their confidence first that we are their sincere well

wishers before trying to exert our authority on them. With growing education

and awareness the situation is improving in India even in the villages [56,57].

Acknowledgements

We wish to express our deep to gratitude to Prof. AK Govila, MD, FAMS, former Dean and Professor of Social and Preventive Medicine for guiding us in many ways. We are also thankful to Mr. A Chaurasia for providing many references for this study. Dr. Lakshmi Misra, MA Ph.D, former Professor of Education has been very kindly provided two important references and has given constant encouragement. Our thanks are also due to Mr. Vijay Birwal in preparation of this article

References

2. Govt of India. Report of Health Survey and Planning Committee (1961) Ministry of Health, New Delhi.

3. Govt of India. National Health Policy, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (2000) New Delhi.

4. Park JE, Chandra H and Sebastian J. A study of bearing of infants at Dabra Primary Health Center, Gwalior, District, Madhya Pradesh (1963) Ind J Pediatrics 30: 143-150. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02748240

6. BelfourM I (1957) : quoted by Bhatia S., I.C.M.R. Special Report, No.32

7. Ranjan A. Maternal Mortality in India (2004) Population Resource Centre, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh.

8. Ranjan A. (2004) Ibid

9. Govt of India. National Population Policy (2001) Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, New Delhi.

10. World Health Organization (1984) A work on how to plan and carry out research work in maternal and child health and FP, Geneva.

11. Blackette, Maurice E, Davies, Michael A, Petros-Barvazian, et al. The risk approach in health care with special reference to maternal and child health (1984) WHO 76. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/39177

13. Chen LC, Gesche MC, Ahmed S, Chowdhury AI and Mosley WH. Maternal mortality in rural Bangladesh (1974) Studies in family planning 5: 334-341. https://doi.org/10.2307/1965185

15. Barno A, Freeman DW and Bellvile TD. Minnesota maternal mortality study (1995) Obse Gyneco 9: 336.

16. Jewett JF. Changing maternal mortality in Massachusetts (1957) New England Journal of Medicine 256: 256: 395-400. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM195702282560905 .

17. Rochat RW. Maternal mortality in USA (1981) World Health Statistics Quarterly 34:3.

18. Rubin G, McCarthy B and Shelton J. The risk of child bearing reevaluated (1981) Stud Fam Plann 26: 201

19. Speckhard ME, Comas-Urrutia AC, Rigau-Perez JG and Adamsons K. Intensive surveillance of pregnancy related deaths (1985) Puertico Rico 77: 508-513.

20. Smith JC, Hogher JM, Pekow PS and Rochat RW. An assessment of the incidence of maternal mortality in the United States (1984) American J Public Health 74: 780-783. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.74.8.780

21. Ziskin LZ, Gregory M and Kreitzer M. Improved surveillance of maternal of maternal deaths (1979) Inter J Obse Gyno 16: 281-286. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1879-3479.1979.tb00445.x

23. Puffer PR and Griffith GW. Patterns of Urban Mortality Washington DC Pan American Health Organization (1967) Scientific Publication.

24. Walker GJA, Ashley DEC, Accaw A and Bernard GW. Maternal mortality in Jamaica (1986) The Lancet 327: 486-488. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(86)92939-9

25. Rubin G, Mc Carthy B, Shelton J and Rochat RW. The risk of child bearing reevaluated (1981) Stud Fam Plann 26: 101.

26. Koenig MA, Fauveau V, Choudhary AJ, Chakraborty MA and Khan. Maternal mortality in Matlab, Bangladesh (1988) Stud Fam Plann 19: 69-80.

27. Egypt Ministry of Healthy (1994) National Maternal Mortality Study : Findings and conclusions, Egypt Ministry of Health

29. Hill AG and Graham WJ. West Africa sources of health and mortality information, a comparative review (1988) Int Dev Res Center, Ottawa.

30. Graham W, Bras W and Snow RW, Indirect estimation of maternal mortality: The sisterhood method (1989) Stud Fam Plann 20: 245.

31. Borema JT and Mati JGK. Studying maternal mortality though networking; results from central Kenya (1987) Stud Fam Plann 20: 245.

32. World Health Organization (1987) Studying maternal mortality in developing countries Rates and causes A guide Book, Geneva, Switzerland.

33. Devraj K, Kulkarni PM and Krishnamoorthy S. An indirect method to estimate maternal mortality ratio (1994) Demography, India, 23: 127.

34. Ranjan A. Maternal mortality in Madhya Pradesh (2004) J fam welf 44: 55.

35. Borema JT. Levels of maternal mortality in developing countries (1987) Stud Fam Plann 18: 213.

36. Blum A and Fargues P. Rapid estimation of maternal mortality in countries with defective data (1990) Population Studies 44: 151-171.1.

37. Ranganathan HN and Rode P. On a method of estimating level of maternal mortality in rural India from limited data (1994) Demography 23: 133S.

38. Fathalla M. The long road to maternal death (1987) People 14: 8-9.

39. Thaddeus S and Maine D. Too far to walk, maternal mortality in context, Center for population and family health (1990) New York.

40. Mc Carthy J and Maine D. A framework for analyzing the determinants of maternal mortality (1992) Stud Fam Plann 23: 23-33. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1966825

41. Government of Madhya Pradesh (2004) Madhya Pradesh Family Welfare Programme Evaluation Survey, RCVP, Noronha Academy of Administration and Management, Population Resource Center of Madhya Pradesh, India.

42. Rao SK, Swaminathan, Swarup S and Patwardhan VN. Protein malnutrition in South India (1959) WHO Bulletin 20: 603-639. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/265361

43. Belavadi B, Pasricha S and Shankar K. Study on lactation and dietary habits of Nilgiri Hill Tribes (1959) Indian J Med Res 47: 221-223.

44. Gopalan C. Effect of protein supplementation and some galactogogues on lactation of poor Indian women (1958) Ind J Med Res 46: 317-324.

45. Mahadevan I. Belief systems in food of the Telugu speaking people of Telangana region (1961) Ind J Soc Work.

46. Gopalan C. Studies on lactation of poor Indian communities (1958) J Trop Paediat 4: 87-97.

47. Pasricha S. A survey of dietary intake of a group of poor and pregnant and lactating women (1958) Ind J Med Res 45: 605-609.

48. Karmarkar MG and Ramakrishnan CV. Relation between dietary fat, fat content of milk and concentration of enzymes in milk (1959) J Nut 69: 274-276.

49. Wickes IG. A history of infant feeding. I. Primitive peoples; ancient works; Renaissance writers (1955) Arch. Disab Child, 28: 151-158. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.28.138.151

50. Davidson WD. A brief history of infant feeding (1953) Jour.Pediat 43: 74-87.

51. Newton NR and Newton M. Relationship of ability to breast feed and maternal attitudes toward breast feeding (1950) J Pediat 5: 869-875.

52. Jaffe DB. (1952) Report on 2nd Inter-African Conf on nutrition, Gambia.

53. Mathes D.S. (1955) : J. of J. Trop. Medicine1, 9

54. Platt B.S. (1954) : Proc. Nutrition Soc., 13, 94

55. Ahluwalia A.S. (1963) : Ind. J. Public Health, VII, 5-8

56. Misra L. Education of women in India (1966) Macmillan Publishers, London.

57. Misra L. Education in Madhya Pradesh and Chhatisgarh (2002) Hindi Granth, Acad.

*Corresponding author

Dr. Bhartendu Shukla, Director of Research, RJN Ophthalmic Institute, Gwalior, India, E-mail:Citation

Shukla S and Shukla B. Social customs and practices associated with pregnancy and child bearing in low socio-economic communities (2020) Nursing and Health Care 5: 18-24.Keywords

Obstetric care, Child bearing, Social customs.

PDF

PDF