Introduction

Economic evaluation in health is a tool used by planners to select an option that offers more advantages based on cost and results presented by intervention, programme or policy. Actions, costs, and consequences are analyzed assisting and contributing to the policy-decision process, providing information to new interventions and health technologies, enabling a resource projection to expand the benefits to a wider population [1]. The need for greater resources allocation in public health programmes, combined with the growing technological sophistication, increased the popularity of economic evaluations. According to Moodie, et al. [2] this popularity was due to the need to prove the efficiency of health programmes, providing information to policy makers when allocating resources for intervention proposals. However, economic evaluation should be conducted and reported accurately to contribute in the definition and value measurements of public health interventions. With the increasing number of publications about economic evaluation in health interventions, the monitoring related to the quality of such assessments became needed. The availability of data obtained from these evaluations has been limited, mostly due to the use of methods that have not been developed for economic analysis in health. Rigorous, high-quality assessments of economic evaluation should become usual, demonstrating conclusively the benefits and merits achieved by public health interventions, and inform the government and community if the investments resulted in any benefit. Among the interventions that need consistent evaluation, there is the School Health Programme. This type of programme consists of an important strategy to enhance learning and the health of children, adolescents and school community. The difficulty in estimating benefits is a challenge for the programmes and to the decision makers, as well as the management of the various funds mainly received from the health and education sectors. Therefore, the aim of this study was to perform a mapping review identifying published articles about the economic evaluation of school health programmes in the past decade, discuss how these studies were conducted and identifying gaps in the literature for further revisions or research to be planned [1-4].

Methods

Results

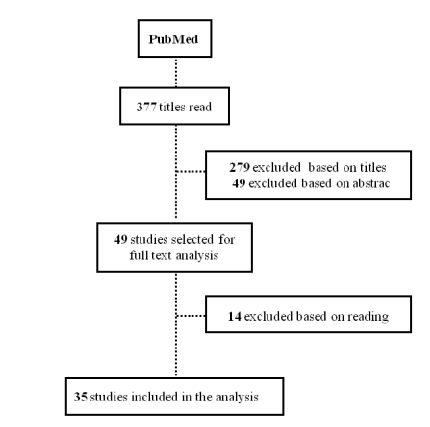

Figure 1: Flowchart of selection process, 2015.

The

studies were performed in United States (57.15%), followed by United Kingdom

(8.58%), Australia (8.58%), Spain (5.72%), Canada (5.72%), European countries

combined (2.85%), Netherlands (2.85%), Sweden (2.85%), New Zealand (2.85%) and

India (2.85%). The type of economic evaluation used by the studies were cost-effectiveness

(51.42%), cost-benefit (17.15%), costs (14.28%), two types of economic analyzes

combined (14.28%) and cost-consequence (2.85%). The authors, country, type of

school health program, and economic evaluation used and the results through cost

and effects measurement adopted are shown in Chart 1.

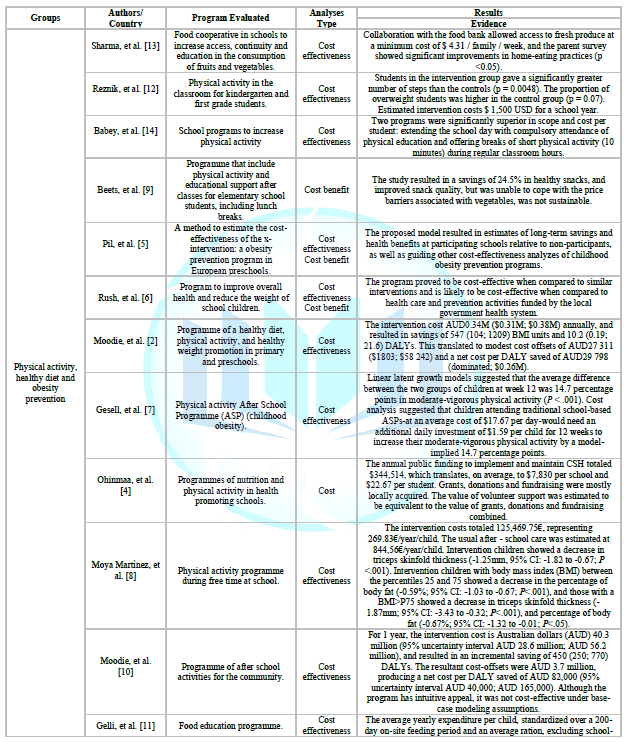

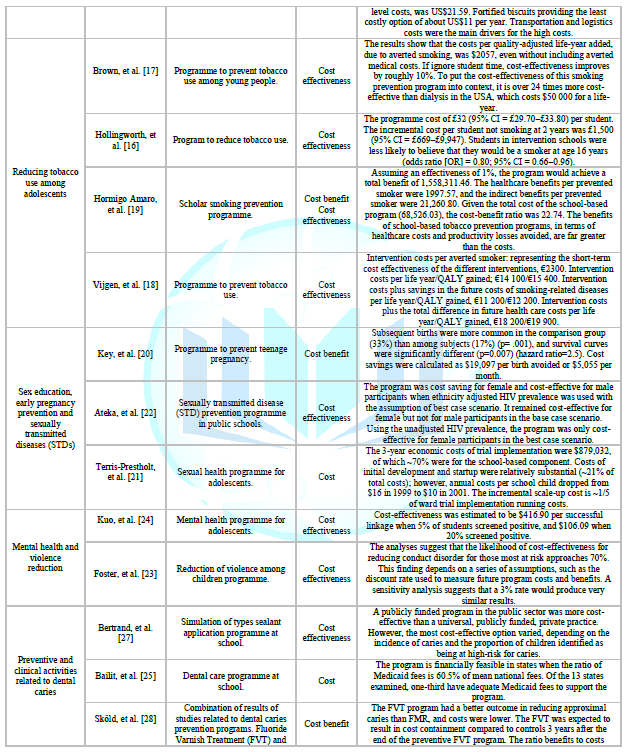

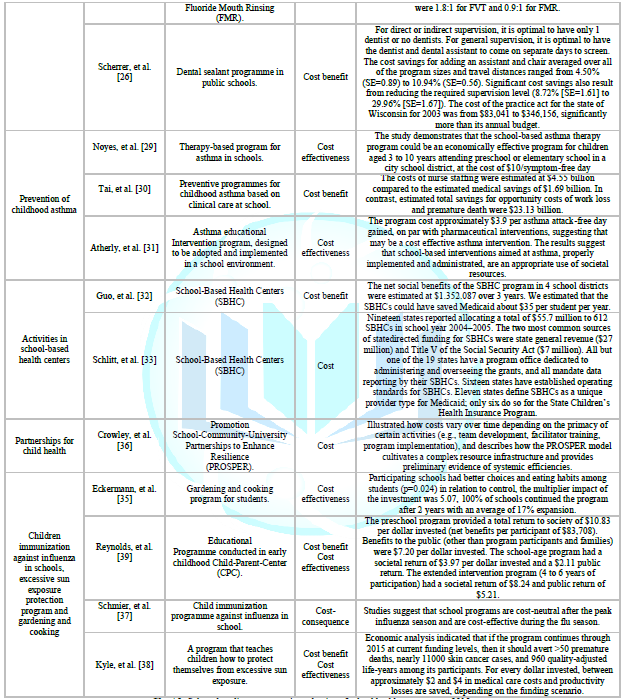

Chart 1:

Selected studies on economic evaluation of school health programmes, 2015

The

narrative synthesis gathered the selected studies in nine groups: (1) physical activity, healthy diet and

obesity prevention; (2) reducing tobacco use among adolescents; (3) sex

education, early pregnancy prevention and sexually transmitted diseases (STDs);

(4) mental health and violence reduction; (5) preventive and clinical

activities related to dental caries; (6) prevention of childhood asthma; (7)

activities in school-based

health centers; (8) partnerships for child health; (9) other studies

represented by a single study of each theme such as: children immunization against

influenza in schools, excessive sun exposure protection program and gardening

and cooking.

Discussion

The present mapping review was performed to

analyse articles published on economic evaluation of school health programmes.

The School Health Programmes can provide one of the most effective means available

for improving the health. The cost-effectiveness was the type of economic

evaluation most used between the studies analyzed. Phillips, et al. [3] discussed

the feasibility and validity of economic valuation techniques to develop

priorities in public health programmes. Health promoters and economists use

different analyses principles, different methodologies, and this can lead to an

adjustment failure between the data provided and the economic evaluation

requirements. From the selected studies, twelve were related to physical

activity, healthy diet and preventing obesity programmes. Studies support the

benefits of childhood obesity prevention programmes through school

interventions, affirming the high potential of prevention of the overweight in

childhood. Eight studies described not only the complete methodology of the

intervention programme but also, how the economic evaluation was performed.

Partnerships

and involvement of the local community, as well as analysis of the context in

which the program will be developed, results in greater impact and

sustainability in relation to reducing costs and achieving positive changes in

the community, children and their families. Interventions performed during

regular school hours and those carried out through the extension of the school

day with compulsory participation are more feasible in relation to reach and

costs per student than pre and post school interventions. It is important to establish a method of

cost-effectiveness analysis, which results in economic estimates, so that the

proposed intervention is worth the money spent [2,4-15]. The approaches used

should ensure that economic assessments can be compared for the purpose of

deciding on the allocation of resources and products. The harmful effects of

smoking are well known in the literature. Four studies were related to tobacco,

which is responsible for thousands of deaths each year in the world, and a

current international action to control its use exists. In recent years,

tobacco prevention at school age and in schools programmes are widely adopted

and have shown to be effective in reducing consumption and early progression.

All

economic evaluation studies presented intervention programmes relatively

low-priced to implement and with high gains to the tobacco user health. Prevention

programmes of sexual and reproductive health are necessary among adolescents

and young adults. The school age mother has strong tendency not to finish her studies,

and the babies are more likely to be born with low weight and/or premature. Also,

the prevention programmes for Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs) in schools

are essential to establish safe sexual behavior before an unsafe occur, improving

knowledge and atitudes [15-22]. The study by Key, et al. [20] behind the

inclusion of social assistance services in school associated with integral

health care for adolescent mothers and their children as an effective

intervention in reducing early pregnancy. In the Terris-Prestholt, et al. [21] study

an economist conducted the data collection, and a timeline was created to

allocate the cost per component. The

study by Ateka, et al. [22] revealed generous differences regarding the degree

of benefits, i.e., the STD prevention program in schools, was more

cost-effective for the feminine sex. The behavior issues among children, and

young adults create personal and social problems related to criminal activity,

illegal substance usage, early sexual initiation and sexually transmitted

diseases [23].

Chart 1: Selected studies on economic evaluation of school health programmes, 2015.

Kuo,

et al. [24] evaluated the cost-effectiveness of a school-based mental health

triage programme, to identify children in need of specific interventions. Cost

effectiveness was calculated by assessing overall costs per successful

screening link. However, the costs associated with increasing the use of

services and long-term effectiveness was not included. Foster, et al. [23] analyzed

the cost-effectiveness of an intensive intervention programme with multiple

components for the prevention of aggressiveness in young children, with early

identification and treatment. The study estimated costs for overheads, and the

program has proven to be cost-effective mainly for untreated and higher-risk

populations, which are particularly costly to society. The studies that

evaluated programmes of preventive and clinical activities related to dental

caries were conceptual and exploratory. Bailit, et al. [25] used national and

international data to estimate expected revenues and expenses for the

school-based programme operation in different states, aiming to reduce the

disparities in access to dental care, examining their financial viability

related to refund rates of a health plan. Scherrer, et al. [26] evaluated the

cost-effectiveness of the School-Based Sealant Programmes (SBSP) in which

different sizes of programmes were modeled with various restrictions over the

practice to compare its efficiency. Bertrand, et al. [27] simulated a public funding

programme of dental sealants in both the public and private sectors and

compared these hypothetical situations. Skold, et al. [28] analyzed two studies

on a prevention program using fluoride varnishes and a prevention program using

fluoride mouthwash and combine the results with a longitudinal study of caries

development in a normal dental care setting in schools.

Asthma

is one of the most common chronic childhood diseases causing morbidity

symptoms, impact on quality of life, limitations of physical activities, no

attendance in schools and loss of working days by the caregivers of the

children with the disease. The studies on prevention programmes for childhood

asthma had different methodologies. Noyes, et al. [29] examined the

cost-effectiveness of the School-Based Asthma Therapy (SBAT) programme in

comparison to the usual care, and the administration of preventive medication

was performed. Tai and Bame [30] examined the cost-effectiveness of a

prevention programme for childhood asthma based on clinical care at schools,

using eight public databases to calculate the costs of the implementation and

the potential savings in reducing the acute emergency and ambulatory. Atherly,

et al. [31] discussed an educational intervention programme on asthma, designed

to be adopted and implemented in the school environment. All these authors

considered that other studies are necessary to justify if these programmes

results in benefits to compensate the additional expenditure, suggested that

these programmes are profitable from a social perspective, i.e., by measuring

all costs and results incurred for society.

The

School-Based Health Center-SBHC provide essential primary care for students

within the schools. Due to its location, they allow overcoming barrier access

such as transportation, lack of service providers, insurance coverage and

parents working schedules and commitment [32]. Schlitt, et al. [33] explored

the current status of the role of SBHCs, the evolution, and expected impact on

long-term sustainability. Guo, et al. [32] analyzed the cost-effectiveness of

SBHCs having as a primary outcome the health care total cost per student. The

authors considered SBHCs cost beneficial to both health system and society, and

should be seen as a health service delivery model to help address the

disparities in health access. There is evidence in the literature related to

the success in achieving partnerships aimed at improving the wellbeing of

children and the adequacy of investments. This partnership can be performed in

different ways between schools and universities, schools and community, schools

and executives, among others [9,34-36]. Crowley, et al. [36] described the

financial and economic cost to install the Promotion School Community

University Partnerships to Enhance Resilience (PROSPER) and reported that costs

vary over time depending on the priority of certain activities, and the

definition of what is essential and necessary to the successful programme

implementation.

One

study presented a successful partnership programme through the involvement of

the community in a gardening and cooking programme, with positive multiplier

impact and return of the initial investment [35]. Evaluating multiplier impacts

from investment on related community activity over time are suggested as

significant evidence of program health effects on targeted groups of

individuals in assessing community network engagement and ownership, dynamic

impacts, and program long term success and return on investment [35]. Different

studies performed economic evaluations in diverse themes. Schmier, et al. [37] performed

a cost-consequence analysis of immunization against influenza in schools using

data from a controlled clinical trial. The results showed that immunization

reduces disease among children and adults and is cost saving to society. Kyle,

et al. [38] evaluated a programme that teaches children how to protect

themselves from excessive sun exposure. They affirm that it is worth educating

children on the subject and that the programme is cost-effective and

cost-benefit with modest impacts on behavior but with a significant reduction

in incidence and mortality from skin cancer. Interventions with early childhood

programmes provide evidence as the most cost-beneficial. Many studies reported

that the programmes total cost were used for evaluation, but did not specify

which were included and excluded, and how they were measured. Most of the

studies mention costs related to the material used and time spent, and only a

few describe administrative expenses and include costs related to the research

construction and technical assistance. Some included costs related to volunteer

time and donated resources, social costs, and opportunity losses. There were a

great variety of research methods used such as interviews, questionnaires,

telephone calls, secondary data analyses, estimates, epidemiological modeling

using mathematical models (DALY and QALY), among others, to determine whether

the programmes could be considered cost effective compared to existing

alternatives [39].

The

authors of this review found, in the included studies distributed worldwide,

the same evidences in the study of Aratani, et al. [40] who discuss about

evidence of the effectiveness of health promotion programmes for adolescents

regarding behavioral changes and improvements in health outcomes, as well as

assessing the costs and benefits of these programmes in the United States. The

article focuses on the discussion of high quality programmes in the

reproductive health area; obesity prevention; mental health and the use of

substances including the tobacco; and prevention of unintentional injuries

(accidents) and violence. It mentions the main studies identified in the

literature that address evidence on avoidable costs of health problems in

adolescents and the cost-effectiveness of the health promotion programmes and

policies. The programmes discussed in the article were not developed

exclusively in the school; they were also developed in communities and clinics,

presenting effective results regarding changes in health risk behaviors and in

the development of healthy habits. Regarding the cost-effectiveness issue, the

programmes are generally likely to be highly cost-effective, however,

programmes have many cost variations, are heterogeneous in its purposes, study

design, scenario composition, making difficult to perform a synthesis by hard

evidence.

The

authors stated that there are efforts to evaluate these programmes in recent

years even considering the challenges related to the difficulty and cost

related to these assessments due to the large sample size, the need for

sophisticated methodologies to isolate the effect of the intervention and the

long-term follow-up. They also affirmed that there is a strong justification

for increasing investments in health promotion for children and adolescents in

the reproductive health areas, obesity prevention, mental health and substance

use, trauma and violence, resulting in a significant decrease in morbidities in

these areas. A few studies, in this mapping review, describe sensitivity

analysis due to estimates analyses for costs and discount rates. According to

Contandriopoulos, et al. [15] two important points that should be addressed in

the economic evaluation studies are the update of costs and effects of the

programme from time to time and the sensitivity analysis. They are essential to

measure the uncertainty impact on the results obtained, certifying its strength

and testing its external validity. Guidelines to evaluate the quality of the

economic evaluations studies have been published in the literature, to

standardize a methodology that could facilitate comparison between the studies.

The

published studies used different approaches to performing economic evaluations,

which made the results difficult to compare. However, the use of these

guidelines are not simple and requires an expert methodological and technical

knowledge. The authors Caffray and Chatterji [41] described the development and

testing of an effective and practical Internet-based cost survey designed by

the authors of the National Assembly on School-Based Health Care (NASBHC) to

capture the costs of school based-health programmes. The economic evaluation

can be conducted from several points of view, whether is the target population,

investor or society. This perspective will determine which costs should be

considered to achieve the result [15]. The study showed that several forms were

used in the estimation and decision of which cost should be included in

calculations (direct, indirect, fixed, variable), with a lack of clarity about

which perspective in the evaluation was performed. Although a high

heterogeneity was presented in the selected studies, they still can contribute

with the economic evaluation knowledge in school health programmes. There is an

issue related to the selection method to perform an economic evaluation of

health since it is not a property or a service, but a condition. Some health

problems affect other people than those directly affected and, there is

uncertainty about the occurrence of diseases. All these factors lead to

uncertainties of the complicated solution, concerning to the resource amount

that should be allocated to health, which services should be prioritized and

financed, and who would be the beneficiaries [15]. It is necessary for an

economic evaluation of credibility to precise definition and description,

within a methodological accuracy that sustain their results. When executed with

quality, they can help decision makers to choose programmes that save resources

and future costs, also provide a projection of possible benefits.

Conclusion

The

selected studies in this mapping review showed different methods, presentation

of included and excluded costs and consequences. Some studies did not contain

an explicit identification of the intervention, perspectives used for the analyzes,

appropriate discounts for programmes that were meant for future periods,

sensitivity analysis, incremental cost-effectiveness analysis, and also

presented generalized results. This study was limited to present a synthesis of

knowledge and relevant aspects to be considered in the economic evaluation of

school health programmes since there are significant variations in conducting

such evaluation. There is evidence that school health programmes can bring

benefits to the target population and society.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Funding: This research

was supported by CAPES Foundation, Ministry of Education of Brazil, Brasilia-

DF, 70.040-020, Brazil (BEX:10349/14-6); CNPq and FAPEMIG.

Conflicts of

interest:

none

References

1. Morgan M, Mariño R, Wright C, Bailey D and Hopcraft M. Economic evaluation of preventive dental programmes: what can they tell us? (2012) Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2: 117-121. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0528.2012.00730.x

2. Moodie

ML, Herbert JK, de Silva-Sanigorski AM, Mavoa HM, Keating CL, et al. The

cost-effectiveness of a successful community-based obesity prevention program:

The be active eat well program (2013) Obesity 21: 2072-2080.

https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20472

3. Phillips

CJ, Fordham R, Marsh K, Bertranou E, Davies S, et al. Exploring the role of

economics in prioritization in public health: what do stakeholders think?

(2011) Eur J Public Health 21: 578-584. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckq121

4. Ohinmaa

A, Langille JL, Jamieson S, Whitby C and Veugelers PJ. Costs of implementing

and maintaining comprehensive school health: the case of the Annapolis Valley

Health Promoting Schools program (2011) Can J Public Health 102: 451-454.

5. Pil

L, Putman K, Cardon G, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Manios Y, et al. Establishing a

method to estimate the cost-effectiveness of a kindergarten-based,

family-involved intervention to prevent obesity in early childhood. The

ToyBox-study (2014) Obes Rev 3: 81-89. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12179

6. Rush

E, Obolonkin V, McLennan S, Graham D, Harris JD, et al. Lifetime cost effectiveness of a

through-school nutrition and physical programme: Project Energize (2014) Obes

Res Clin Pract 8: 115-122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orcp.2013.03.005

7. Gesell

SB, Sommer EC, Lambert EW, Vides de Andrade AR, Whitaker L, et al. Comparative

effectiveness of after-school programmes to increase physical activity (2013) J

Obes. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/576821

8. Moya

MP, Sánchez LM, López BJ, Escribano SF, Notario PB, et al. Cost-effectiveness

of an intervention to reduce overweight and obesity in 9-10-year-olds. The

Cuenca study (2011) Gac Sanit 25: 198-204. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0213-91112011000300005

9. Beets

MW, Tilley F, Turner-McGrievy G, Weaver

RG and Jones S. Community partnership to address snack quality and cost in

after-school programmes (2014) J Sch Health 84: 543-548. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12175

10. Moodie

ML, Carter RC, Swinburn BA and Haby MM. The cost-effectiveness of Australia's

active after-School Communities program (2010) Obesity 18: 1585-1592. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12175

11. Gelli

A, Al-Shaiba N and Espejo F. The costs and cost-efficiency of providing food

through schools in areas of high food insecurity (2009) Food Nutr Bull 3:

68-76. https://doi.org/10.1177/156482650903000107

12. Reznik

M, Wylie-Rosett J, Kim M and Ozuah PO. A classroom-based physical activity

intervention for urban kindergarten and first-grade students: a feasibility

study (2015) Child Obes 11: 314-324. https://doi.org/10.1089/chi.2014.0090

13. Sharma

S, Helfman L, Albus K and Pomeroy M, Chuang RJ, et al. Feasibility and

acceptability of brighter bites: A food Co-Op in Schools to increase access,

continuity and education of fruits and vegetables among low-income populations

(2015) J Prim Prev 36: 281-286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-015-0395-2

14. Babey

SH, Wu S and Cohen D. How can schools help youth increase physical activity? An

economic analysis comparing school-based programs (2014) Prev Med 69: 55-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.10.013

15. Contandriopoulos

AP, Lachaine J and Brousselle A. Economic evaluation (2011) Brouselle A,

Champagne F, Contandriopoulos AP, Hartz Z, et al. Rio de Janeiro Fiocruz 9:

183-216.

16. Hollingworth

W, Cohen D, Hawkins J, Hughes RA, Moore LA, et al. Reducing smoking in

adolescents: cost-effectiveness results from the cluster randomized ASSIST (A Stop

Smoking In Schools Trial) (2012) Nicotine Tob Res 14: 161-168.

https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntr155

17. Brown

HS, Stigler M, Perry C, Dhavan P, Arora M, et al. The cost-effectiveness of a

school-based smoking prevention program in India (2013) Health Promot Int 28:

178-186. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dar095

18. Vijgen

SM, van Baal PH, Hoogenveen RT, de Wit GA and Feenstra TL. Cost-effectiveness

analyses of health promotion programmes: a case study of smoking prevention and

cessation among Dutch students (2008) Health Educ Res 23: 310-318.

https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cym024

19. Hormigo

AJ, García-Altés A, López MJ, Bartoll X, Nebot M, et al. Cost-benefit analysis

of a school-based smoking prevention program (2009) Gac Sanit 23: 311-314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gaceta.2009.01.013

20. Key

JD, Gebregziabher MG, Marsh LD and O'Rourke KM. Effectiveness of an intensive,

school-based intervention for teen mothers (2008) J Adolesc Health 42: 394-400.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.09.027

21. Terris-Prestholt

F, Kumaranayake L, Obasi AI, Cleophas-Mazige B, Makokha M, et al. From trial

intervention to scale-up: costs of an adolescent sexual health program in

Mwanza, Tanzania (2006) Sex Transm Dis 10: 133-139.

https://doi.org/10.1097/01.olq.0000200606.98181.42

22. Ateka

GK and Lairson DR. School-based HIV/STD prevention programmes: do benefits

justify costs? (2008) J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care 7: 46-51. https://doi.org/10.1177/1545109707304446

23. Foster

EM and Jones D. Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. Can a costly

intervention be cost-effective? An analysis of violence prevention (2006) Arch

Gen Psychiatry 63: 1284-1291. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.63.11.1284

24. Kuo

E, Vander SA, McCauley E and Kernic MA. Cost-effectiveness of a school-based

emotional health screening program (2009) J Sch Health 79: 277-285. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00410.x

25. Bailit

H, Beazoglou T and Drozdowski M. Financial feasibility of a model school-based

dental program in different states (2008) Public Health Rep 123: 761-767. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335490812300612

26. Scherrer

CR, Griffin PM and Swann JL. Public health sealant delivery programmes: optimal

delivery and the cost of practice acts (2007) Med Decis Making 27: 762-771. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989X07302134

27. Bertrand

E, Mallis M, Bui NM and Reinharz D. Cost-effectiveness simulation of a

universal publicly funded sealants application program (2011) J Public Health

Dent 71: 38-45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-7325.2010.00200.x

28. Sköld

UM, Petersson LG, Birkhed D and Norlund A. Cost-analysis of school-based

fluoride varnish and fluoride rinsing programs (2008) Acta Odontol Scand 66:

286-292. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016350802293978

29. Noyes

K, Bajorska A, Fisher S, Sauer J, Fagnano M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of the

School-Based Asthma Therapy (SBAT) program (2013) Pediatrics 131: 709-717. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-1883

30. Tai

T and Bame SI. Cost-benefit analysis of childhood asthma management through

school-based clinic programmes (2011) J Community Health 36: 253-260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-010-9305-y

31. Atherly

A, Nurmagambetov T, Williams S and Griffith M. An economic evaluation of the

school-based "power breathing" asthma program (2009) J Asthma 46: 596-599. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770900903006257

32. Guo

JJ, Wade TJ, Pan W and Keller KN. School-based health centers: cost-benefit

analysis and impact on health care disparities (2010) Am J Public Health 100:

1617-1623. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.185181

33. Schlitt

JJ, Juszczak LJ and Eichner NH. Current status of state policies that support

school-based health centers (2008) Public Health Rep 123: 731-738. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335490812300609

34. Jayaratne

K, Kelaher M and Dunt D. Child Health Partnerships: a review of program

characteristics, outcomes and their relationship (2010) BMC Health Serv Res 10:

172. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-10-172

35. Eckermann

S, Dawber J, Yeatman H, Quinsey K and Morris D. Evaluating return on investment

in a school based health promotion and prevention program: the investment

multiplier for the Stephanie Alexander Kitchen Garden National Program (2014)

Soc Sci Med 114: 103-112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.05.056

36. Crowley DM, Jones DE, Greenberg MT, Feinberg ME and Spoth RL. Resource consumption of a diffusion model for prevention programmes: the PROSPER delivery system (2012) J Adolesc Health 50: 256-263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.07.001

37. Schmier

J, Li S, King JC, Nichol K and Mahadevia PJ. Benefits and costs of immunizing

children against influenza at school: an economic analysis based on a large-cluster

controlled clinical trial (2008) Health Aff (Millwood) 27: 96-104.

https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.w96

38. Kyle

JW, Hammitt JK, Lim HW, Geller AC, Hall-Jordan LH, et al. Economic evaluation

of the US Environmental Protection Agency's SunWise program: sun protection

education for young children (2008) Pediatrics 121: e1074-1084.

https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-1400

39. Reynolds

AJ, Temple JA, White BA, Ou SR and Robertson DL. Age 26 cost-benefit analysis

of the child-parent center early education program (2011) Child Dev 82: 379-404. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01563.x

40. Aratani

Y, Schwarz SW and Skinner C. The economic impact of adolescent health promotion

policies and programs (2011) Adolesc Me State Art Rev 22: 367-386.

41. Caffray

CM and Chatterji P. Developing an Internet-based survey to collect program cost

data (2009) Eval Program Plann 32: 62-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2008.08.009

*Corresponding author

Fernanda

Piana Santos Lima de Oliveira, Fipmoc University Center, Montes Claros, Minas

Gerais, Brazil, Tel: +55 (31) 98449-7715, E-mail: fernandapiana@gmail.com

Citation

Oliveira de FPSL, Moita GF, Ferreira EFE, Drummond AMA, Vargas AMD, et al. Economic evaluation of school health programmes: a mapping review (2005-2015) (2020) Nursing and Health Care 5: 33-40.

Keywords

Cost, Economic evaluation, School health.

PDF

PDF