Introduction

Epistemology

is the branch of philosophy that addresses cognitive sciences, the history of science

and cultural studies. It investigates the origin, methods, nature, and limits

of knowledge. It seeks to determine what we know, how we know it and is used to

determine truth or falsehood as we seek to acquire knowledge of our world.

Swarming in patient care made an initial impact in nursing when The University

of Kentucky Healthcare in Lexington, UK created a standardized approach to

investigate Root Cause Analysis (RCA) in 2009. Since then, swarming in nursing

is described in different ways. For instance, RCAs were referred to as

Swarming. Another description of swarming was of a tool, which was designed to

recognize inefficiencies in staff communication. Another example described

Swarming as a swift evaluation of the patient by the healthcare team and the

final description of SWARM was described as a type of gathering to discuss the

events of a fall. Nevertheless, limited sources described events of swarming directly

in nursing and the ones that did were difficult to access and not open source.

To fill this gap, we presented a review of the various examples of swarming and

recommended a novel approach of how swarming may be utilized in Intensive Care

Units (ICUs) [1,2].

Aim

We reviewed the research literature and examined the epistemology of swarming in patient care. The admission process of patients into ICUs can be busy to utterly chaotic at times. To the untrained eye, staff may be observed milling around in a small space trying to stabilize and provide care to patients. In order to provide some semblance of structure, to prevent duplication of tasks and to ensure required tasks for standard of care are completed, we recommended an innovative approach to assist the nursing staff when admitting critical patients into ICUs.Method

Electronic

databases CINAHL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, ProQuest, PubMed and the Internet

were searched using the terms “swarming” and “nursing”. Although the

recommendations are not a formal guideline, the AGREE checklist was used to

develop this manuscript. No restrictions of published dates were placed. The

target populations were patients and articles that discussed the use of

swarming in patient care were selected. All articles that included swarming of

insects were excluded. There were limited articles available on the use of

swarming in patient care. Three articles were published by the Joint

Commission, another by America’s Essential Hospitals, and the next was as a

letter to the editor of the Annals of Emergency Nursing. A systematic review

was conducted on these works and the examples outlined below.

First Example

of SWARM

RCA

is a universal approach used to investigate undesirable vulnerabilities in

health care systems. From this research, RCAs were colloquially termed

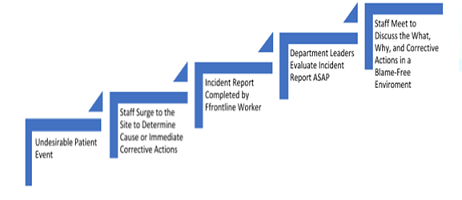

Swarming. The authors described five key steps to a SWARM. The process usually

begins with an unwanted patient event; staff SWARMs to the site to determine

cause or immediate corrective actions; an incident report is completed by the

front-line worker; department heads review and evaluate the report as soon as

possible; and then a meeting is set up for staff to determine what happened,

why it happened and how to prevent the event from happening again see Figure 1. A meeting is then conducted

in a neutral blame-free environment, introducing the process, the plan, purpose

and the legal protections for staff who speak up. Everyone in the room is

introduced, the facts of the incident are reviewed, discussion of the incident

with any contributing factors and finally, proposed action plan, assignment of

individuals to take ownership for additional investigations and implementation

of a plan of action [2].

Second Example of

SWARM

Williams

et al., [3] used a quality improvement process to recognize, evaluate and

encourage open dialogue with front-line workers to improve problem solving in a

Pediatric ICU (PICU). The authors created a tool to empower caregivers to share

information about problems or perceived problems and to quickly develop

solutions in order to eliminate errors, process improvement and to develop a

system of high reliability. The SWARM tool was designed to identify

communication and inefficiencies in performance to develop an infrastructure of

high reliability when managing problems. The approach to a problem specific

SWARM begins by consulting upstream and downstream stakeholders in order to

understand the scope of a problem. There is the use of an electronic tracking

system to list the problems in categories, as well as possible solutions. Then,

there is a process to disseminate learning opportunities to the involved

caregivers on the specific units [3].

Third Example of

SWARM

In a letter to the Editor of the Annals of Emergency Department (ED), Perniciaro and Liu described the redesign process of a Pediatric ED with upwards of 80,000 visits per year. The authors described Swarming as the instant evaluation of the patient together with the nurse, resident, and senior ED physician. Historically, in the ED a patient was initially assessed by the nurse, and then a medical assessment was performed by the physician.

Figure 1: The Process of Swarming.

However,

in their new model, patients were sorted quickly into tracks, placed in beds

without the usual triage process, physicians were placed into zones, and

patients were moved into treatments-in-progress and discharge areas. By

eliminating the traditional serial workflow, efficiency was garnered via

concurrent assessment of patients and education of residents. Using this

process, this ED saw a drastic reduction in wait times and residents were able

to model the senior medical staff. The authors asserted to have given birth to

the concept of "swarming," and concluded that Swarming as a new

process seem promising, but has several disadvantages including its efficacy

and individual variability [4].

Fourth

Example of SWARM

Motuel

et al., [5] described a patient safety incident that occurred in a UK hospital.

SWARM was described as a type of post incident huddle that was performed soon

after the event in order to make improvements. SWARM was compared to RCAs as a

superior tool because it stressed a blame-free culture with a focus on

addressing the underlying issues. This example builds upon the standard

approach and seminal work of Li et al, on how to investigate safety events that

affect patients [2].

Reasons for ICU

Admissions

The

Society for Critical Care Medicine reported on the vital statistics of patients

who end up in ICUs in the U.S. Nearly six million patients are admitted per

year, needing invasive monitoring, airway support, and stabilization of life

threatening conditions, management of illness or injuries, restoration of

homeostasis, or care for the dying patient in a collaborative and

interdisciplinary environment. About 20% of acute Care patients are admitted to

ICUs, with approximately 58% of ED patients resulting in ICU admissions. The

most common ICU admissions are septicemia, percutaneous cardiovascular

procedures, cerebral/myocardial infarction, and respiratory system diagnosis

with up to 30% of patients requiring ventilatory support. The admission process

of this patient population into ICUs can be busy to downright chaotic [6].

Swarming in ICU

Admissions

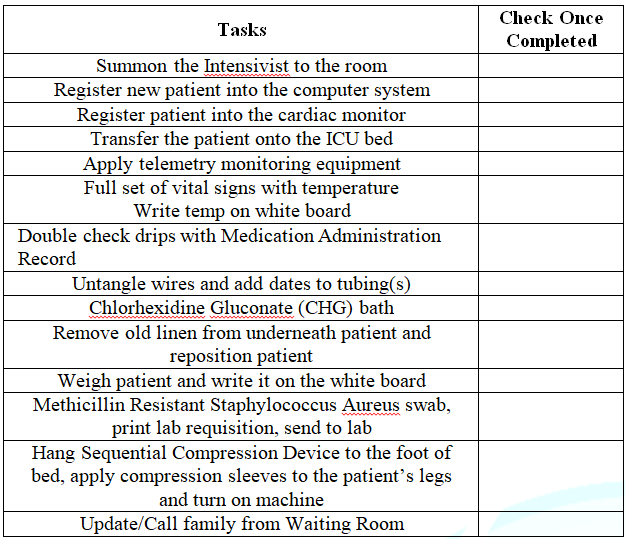

Critically ill patients are often transported from EDs, Operating Rooms, other areas within a hospital system, or from Critical Care Transport. Generally, the receiving staff for a patient in the ICU include a Registered Nurse (RN), a respiratory therapist, and an Intensivist (physician who specializes in critical care medicine). In order to have the best outcomes, several actions are often performed simultaneously. During this period, an “all hands-on deck” approach is used where all available staff SWARM into the room to help. Nurses may be observed performing tasks like hooking the patient up to a cardiac monitor or trying to start peripheral intravenous lines. There is usually no structure to these practices. Some would agree this is the culture of the ICU where nurses show up, lend a hand, and then return to their assigned patients. As the helpers are busy attempting to stabilize the patient, the primary RN should ensure the medications and equipment are verified for activation and correct settings. Some of the tasks needed once the patient arrives into the ICU suite are for the primary RN to receive a bedside report from the healthcare team, often using the framework called SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation). Timely tasks include logging into the Electronic Health Record to start and or pend the admission note. Other simultaneous tasks are listed in the admission to ICU tasks checklist (Table 1) [7].

The

assumption is the primary RN will be familiar with the healthcare team located

in the ICU and feel comfortable with them to designate some of these tasks.

Like processes used in the ED by Perniciaro and Liu to optimize clinical

efficiencies, swarming could be used in ICUs to prevent duplication of tasks.

We recommend the primary RN assign tasks to staff who show up to help. The

checklist may be taped on the entrance door into the ICU and staff who complete

a task may check the right-hand side of the checklist to express completion.

Once the team returns to their designated areas, the primary RN will need to

verify, but not have to spend a long time completing the tasks alone. This

checklist may also be a good tool to communicate with oncoming staff at the

change of shift. The checklist may be updated as needed by the nursing staff to

fit their ICUs and to include tasks specific to their workflow [4].

Table 1: Admission to ICU Tasks Checklist.

Limitations

A

standard definition of Swarming does not exist. Besides the benchmark study by

Li et al., there is limited research on the use of Swarming in healthcare and

no mention of its use in any ICUs. Swarming ICU patients would rely on the

number of available staff to help to stabilize patients. When staff SWARM to a

patient during the ICU admission process, the environment can seem chaotic, but

quick assignment of roles before patient arrival or on arrival to the ICU may

guide staff to be more efficient. The goal is to reduce the number of tasks for

the primary RN to perform, freeing up time for continual assessment of the

critically ill patient [2,5].

Conclusion

The epistemology of Swarming in patient care revealed that it is a colloquial term created by a British hospital system in 2009 to describe RCAs. We described four examples of Swarming found in the nursing literature. Each example was unique and described measures to improve patient safety, and or ways to improve efficiencies in workflow through communication and performance. When the Swarming process was used in the ED, it helped to improve delays and prevented frustrations from patients answering repetitive questions. Similarly, Swarming a patient during the admission process in ICUs may improve communication amongst staff and help the primary RN to perform continual assessments in the stabilization of critical patients. No best practice exists on how to SWARM admitted patients into ICUs, but this process is performed by nurses daily and lacked a name until now. We believe the use of our checklist could enhance the ICU admission process and be used as a tool to streamline tasks, thus avoiding duplication and supporting the primary RN.

References

1. Bourgeois

N. (2011). An epistemology of leadership perspective.

2. Li J, Boulanger B, Norton J, Yates A and Swartz. Swarming

to improve patient care: A novel approach to root cause analysis (2015) Joint

Commission J Qual Pati Saf 41: 494-501.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S1553-7250(15)41065-7

3. Williams EA, Nikolai D, Ladwig L, Miller C and

Fredeboelling, E. Development of swarm as a model for high reliability, rapid

problem solving, and institutional learning. Joint Commission (2015) J Qual

Pati Saf 41: 508-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2008.08.009

4. Perniciaro J and Liu D. Swarming: A new model

to optimize efficiency and education in an academic emergency department (2017)

Annals Emerg Med 70: 435-436. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.05.012

5. Motuel L, Dodds S, Jones S, Reid J and Dix A.

Swarm: A quick and efficient response to patient safety incidents (2017)

Nursing Times 113: 36-38.

6. Society of

Critical Care Medicine (2019) Critical care statistics.

7. Liverpool

Hospital (2017 February). ICU guideline: Clinical guidelines, receiving a

patient into ICU.

*Corresponding author

Aretha D Miller, Nursing Department, Aspen

University, Denver, USA, E-mail: aretha.miller@aspen.edu

Citation

Miller DA and Stephenson C. The epistemology of swarming in patient care: an innovative approach to admitting patients into intensive care units (2021) Nursing and Health Care 5: 41-43.Keywords

Swarming, Critical care, ICU, Admission

PDF

PDF