Research Article :

Matiang’i M, Okoro D, Ngunju P,

Oyieke J, Munyalo B, Muraguri E, Maithya R and Mutisya R Background:

Covid-19

is a rapidly evolving pandemic, affecting both developed and developing

countries. Maternity services in low resource countries are adapting to provide

antenatal and postnatal care midst a rapidly shifting health system environment

due to the pandemic. Objectives: The

objective of the study was to determine the effect of COVID-19 on maternity

services in selected levels III and IV public health facilities within five

MNCH priority counties in Kenya. Method:

A two-stage sampling approach was used to select health facilities. The

study employed cross-sectional and observational retrospective approaches. Data

was collected from Maternity facilities managers and registers in a total of 28

levels III and IV facilities. Open Data Kit (ODK) formatted tools were used to

collect data. Data was analysed using STATA Version 15. Descriptive statistics,

Chi-square and fishers exact tests were used to analyse data. For all tests, a

p-value <0.05 was taken as statistically significant. Results: A total of 31 midwifery managers were interviewed and a

total of 801 maternity records (400 before COVID and 401 during COVID-19

pandemic) were reviewed from levels III (66%) and IV (34%) facilities. The

managers indicated that Antenatal Care (ANC) visits had reduced (67.9%),

referrals of mothers with complications got delayed (29%), mothers feared

delivering in hospitals (64.5%). The managers reported that New-born care

services were most affected by the pandemic (54.8%) followed by ANC services (45.2%).

Facility records revealed a 19% higher ANC attendance before COVID than during

the pandemic. Neonatal deaths increased significantly during Covid-19 period

((P=0.010) by 38%. Live births significantly increased during the pandemic (p <0.0001).

Significant increases also observed in mothers who developed labour

complications (p=0.0003) and number of mothers that underwent caesarean

sections (p <0.001) during the pandemic period. Conclusion: The fear of the

Covid-19 pandemic had a cross-cutting effect on utilisation of maternity

services. COVID-19

pandemic appeared for the first time in Wuhan City of China in 2019; and spread

nearly to include all other countries all over the world. Since this time, it

continues to present a great life challenge affecting all aspects of humans

including health and economic matters [1]. According to WHO, globally adverse

maternal and new-born care outcomes have been on a downward trend [2]. Midwives

are currently among the frontline health workers who are suffering the impact

of the Covid-19 pandemic [3]. Midwives are the pillar of Maternity and

Reproductive health programmes and the face of health services delivery among

frontline health workers. Midwives help with most of the 130 million deliveries

that occur every year in the world [4]. In

Kenya, there have been reports of decreased antenatal attendance,

immunisations, and hospital deliveries, along with an increase in stillbirths

during COVID-19. The decline may be as a result of restricted access to health

facilities arising from city lockdowns and curfews imposed by the government,

where pregnant women and their companions feared harassment and arrest by the

police. Additionally, fear of contracting COVID-19 may keep many women from

attending reproductive health services. Similar issues were raised during the

recent Ebola pandemic [5]. According to the Kenya Ministry of Health (MOH),

level III facilities provide primary care services but with additional support.

They include health centres, maternity and nursing homes. Many are currently

able to offer in-patient services, mostly maternity. These facilities usually

receive referrals from level I and II facilities. On the other hand, level IV

facilities are the first-level hospitals whose services complement the primary

care level. Together with level V facilities, these form the county referral

hospitals. Majority of the referrals to this level are from levels II &

III. Facilities at this level offer in- and out-patient services and have large

laboratories that offer diagnostic services that otherwise would not be

available at the primary care facilities. In emergency cases, referrals to this

level may also come from Level I [6]. A review of the

existing literature demonstrates there is information gap on the effect of

coronavirus disease (COVID-19) to midwifery services in five Counties in Kenya.

Therefore, the current study aimed to assess the effect of COVID-19 on

maternity services in selected levels III and IV public health facilities

within 5 MNCH priority counties in Kenya. Study setting: The study was

conducted in selected levels III and IV facilities located within the UNFPA and

MOH, MNCH priority counties. Kilifi County is found on the coastal part of the

country, Migori on the Western, Garissa on the Northern part, Isiolo on the

Eastern while Nairobi is the capital city of Kenya. A total of 28 health

facilities in 17 sub-Counties were reached across the five counties. Study design and

Procedure: The

study employed both cross-sectional and observational retrospective study

design. Data was collected from maternity units managers and previous

registers. Data collection focused on how Covid-19 had affected access to and

utilization of maternity services by pregnant women four months before covid-19

and four months during the covid-19 period. Before extracting the information

or talking to the midwifery managers, investigators explained the objectives of

the research and assured the participants of their confidentiality. A total of

31 managers were interviewed and 801 maternity records were reviewed from all

the selected level III and IV facilities. The facilities were randomly chosen

from MoH master health facility list at the county level. Study variables: The questionnaire

included information on the County, level of facility, duration of service and

education level of the health workers. It also included the potentially

affected health services and source of information on COVID-19. It also

included ANC visits, access to skilled birth attendance information and

services, post-natal care attendance and follow-up. Data collection: A two-days

training programme comprising of introduction to study objectives and

instruments as well as review of the instruments, practice interviews and data

collection was conducted. To improve on data accuracy and reduce data entry

errors, the selected enumerators were trained on data collection using mobile

phones (ODK). Research Assistants (RAs), were recruited and trained from each

of the 5 counties based on a set criterion; included ability to use computers

and mobile phone applications, training in health or social sciences, and

familiarity with the respective region or county. The tools were piloted in a

facility external to the counties of interest and feedback shared for any

corrections before actual data collection commenced. Quantitative data

checklist with variables of interest, were used in interviewing respondents.

The quantitative instruments were piloted during the training of research

assistants. Due to COVID-19, all the enumerators were given masks and

sanitizers for the entire period that they were in the field. Statistical

analysis: The

quantitative data was analysed using STATA Version 15. Descriptive statistics,

such as frequency counts, percentages, mean, and standard deviation were used

to analyse the demographic details of the respondents and health related

variables of interests. Cross tabulation, chi-square test and fishers exact

test were used to find association between selected maternity care indicators and

selected time intervals of the pandemic. For all tests, a p-value <0.05 was

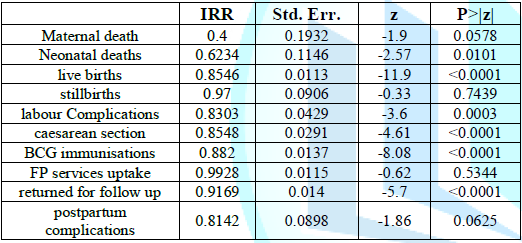

taken as statistically significant. Incidence Rate Ratio (IRR) was also

calculated to establish mothers’ comparative risk exposure before and during

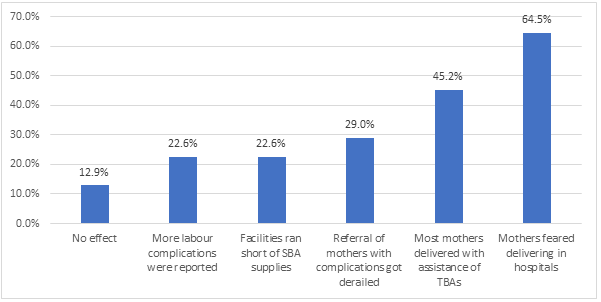

the pandemic. Social-Demographic

results: A

total of 31 midwifery managers were interviewed and a total of 801 maternity

records reviewed from the selected public health facilities in 5 MNCH priority

counties in Kenya. Level III facilities accounted for slightly over half

(51.6%) of the facility manager respondents. The records reviewed were

proportionate to the number of levels III and IV facilities in each of the

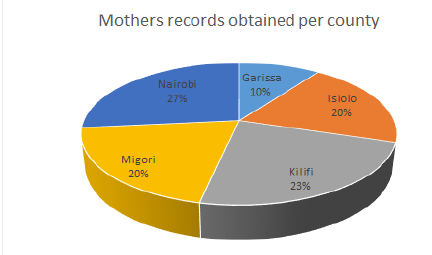

selected five counties (Figure 1).

It emerged that 71.7% of the files reviewed belonged to unemployed (housewife)

mothers of whom 92.1% were married. For the interviewed facility maternity

managers, 48.4% of them had worked for 1-3 years in their current station and

the highest level of professional education for most of them (67.7%) was a

diploma in either nursing or midwifery (Table

1). Figure 1: Mothers records obtained per county. Table 1: Demographic Characteristics of the Midwifery Managers (N= 31). Managers

perceptions on the effect of Covid-19 on maternity services and facilities

preparedness: According

to the managers, COVID 19 affected women’s utilization of ANC services given

that ANC visits reduced (67.9%), with the 1st ANC visits reducing by (50%). Only

3.6% of the managers responded that 1st ANC visits increased majority being

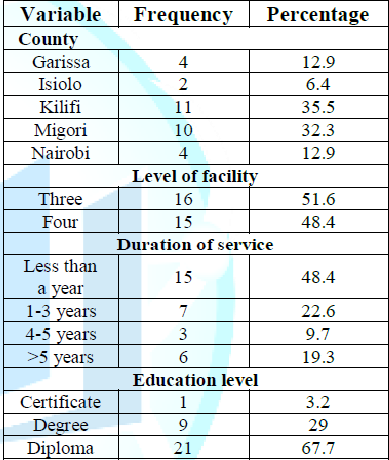

from facilities that acted as referral centres. Provision of midwifery services

was similarly affected; 58.1% of the managers reported that emergency services

were available, 51.6% of the managers indicated that the services were not

affected while 41.9% of them were of the opinion that midwives had limited

opportunities to carry out routine ANC visitations in the community (Figure 2). On

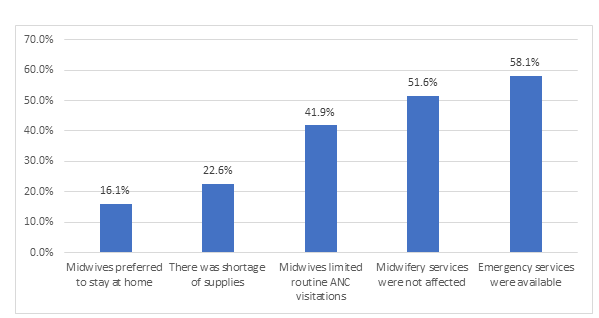

Skilled Birth Attendance, the mangers responded that mothers feared delivering

in hospitals (64.5%), some mothers were delivering with the assistance from

TBAs (45.2%) and referrals of mothers with complications was getting delayed

(29%) as a result of the government instituted movement restrictions that

affected the whole country. The managers also observed that during COVID-19

there was an increase in cases of Gender Based Violence (71%), unplanned

pregnancies (90.4%) and still births (48.3%). They also indicated that uptake

of FP commodities had reduced (64.5%), uptake of immunization services was low

(80.6%) and opportunities for educating antenatal mothers were quite limited by

the pandemic (83.9%). Figure 2: How Covid-19 affected the provision of Midwifery services. A

total of 25(80.7%) facility managers confirmed that midwives received training

on how to handle reproductive health clients during the covid-19 pandemic. More

than a third (35.5%) of the facilities according to the managers were operating

below the capacity, 9(29%) were running at a normal capacity, 6(19.3%) on

average while 5(16.1%) were above their capacity especially those that were

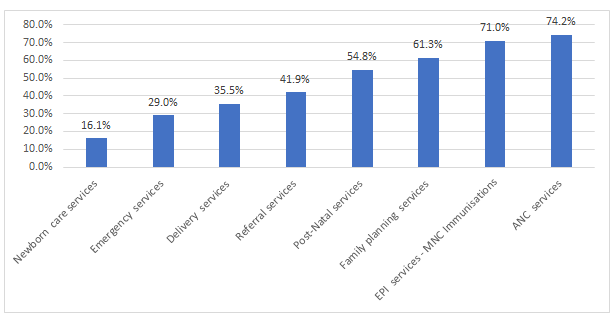

serving as referral centres. The most affected perinatal services according to

the managers were ANC services (74.2%), EPI services (71%), family planning

services (61.3%) and post-natal services (54.8%). The least services affected

were new-born care services (16.1%) and emergency services (29%) as depicted in

Figures 3 and 4. Figure 3: How COVID-19 affected Skilled Birth Attendance (SBA) services. Figure 4: Managers perceptions on how Covid-19 affected perinatal services. The

major source of information on Covid-19 for the health workers was national

guidelines (74.2%), trainings by the hospital (64.5%) and MOH/County website

(51.6%). Social media ranked fourth (41%) while WHO website was (25.8%). No

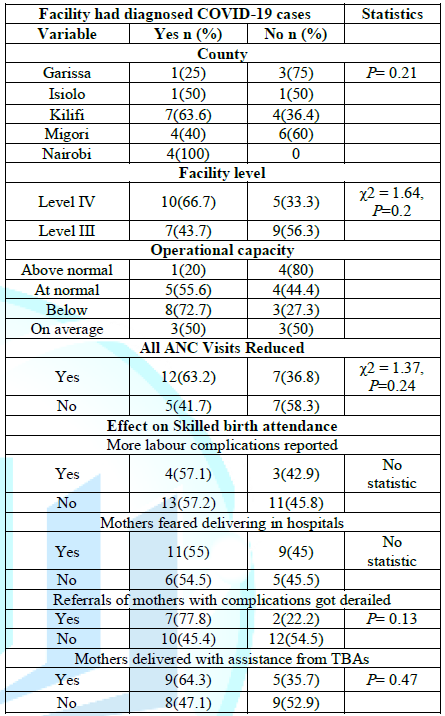

association was found between the facilities that had diagnosed COVID-19 cases

with their socio demographic characteristics and other health related

variables. However, more cases were reported in Nairobi City County and level

IV hospitals. In addition, out of the 11 facilities that were operating below

the normal capacity, 72.7% had a COVID-19 case diagnosed in them. As far as ANC

visits were concerned, more than two thirds (63.2%) of the reduced ANC visits

were among the facilities that diagnosed COVID-19. More than three quarters

(77.8%) of referrals of mothers that were delayed and 64.3% of reported cases

of mothers who delivered with assistance from TBAs occurred in facilities that

diagnosed COVID-19 cases as depicted in Table

2. Table 2: Cross-tabulation between facilities who had diagnosed COVID-19 cases with other variables. Effect of

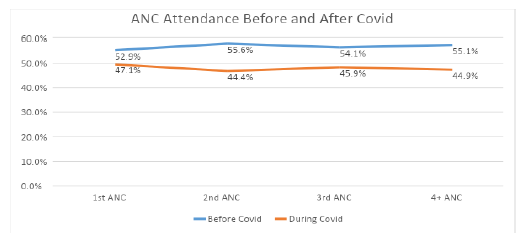

Covid-19 on pregnancy outcomes ANC services: Data extracted

from the facilities supported the maternity facility manager’s opinions; 1st,

2nd, 3rd and 4 Plus ANC visits revealed 5 a mean reduction during Covid-19 as

shown in Figure 5. The results

indicate a difference in the proportion of mothers attending ANC clinics with

lower proportion observed during COVID as compared to Pre-Covid-19. This was

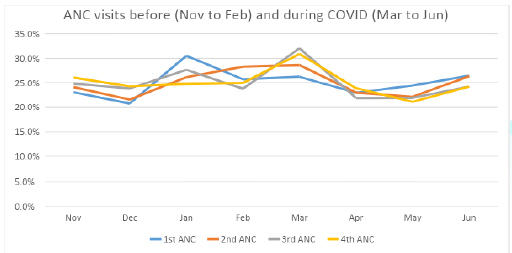

true across the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th ANC visits before COVID. Figure 6 highlights the high decline in

mothers attending ANC clinics in later visits as compared to earlier visits.

Further analysis indicated that cumulatively, ANC attendance was 19% higher

before Covid-19 than during the pandemic. Facility data indicated a decline in

the proportion of ANC visits for all the four visit in the early months after

COVID-19 cases were reported in the country (between March to May 2020) and

thereafter an increase in the number of visits was observed between months of

May and June 2020 when movement restrictions got lifted as depicted in figure

6. Maternal deaths: Facility data

indicated a sharp increase in the number of maternal deaths in the early months

after COVID-19 cases were reported in the country (between month 5 (14.3%; n=3)

and 6(28.6%; n=6) compared to the cases before COVID-19 (month 4 (9.5%; n=2).

Thereafter a reduction in the number of maternal deaths was observed between

months 6 to 8 (4.8%; n=1) when movement restrictions got lifted. Despite the

reduction in absolute numbers (Table 3),

further analysis found no sufficient evidence that maternal deaths were significantly

affected by COVID-19 (p=0.05784). Figure 5: Trends of ANCvisits comparison before and during Covid-19. Table 3: Effect of Covid-19 on pregnancy outcomes. NB:

IRR of <1 suggest increase risk to the exposed group (during Covid-19) To

get the percent chance the (1-IRR) e.g. Maternal death 1-0.4 = 0.6 interpreted

as 60% difference of incidence between before and during Covid-19) Since the

IRR is <1 it means increased risk to the exposed thus 60% increase in

numbers. The P> |z| indicates if the IRR is significant based on the std

error and the z values. As is the standard case any value <=0.05 is

significant. Neonatal Deaths: The number of

neonatal deaths reported in facilities between month 4(6.4%; n=8) and 5(24.8%;

n=31) which were months when the first COVID-19 cases were reported increased.

After month 5, the number of neonatal deaths were observed to decrease up to

month 6(11.2%; n=14) with minimal changes in numbers between month 6 and

8(12.8%; n=16) this being the period when movement restrictions got lifted.

Overall the increase of neonatal mortality increased significantly during

covid-19 pandemic at P= 0.010). Live Births and

Still Births: An

upward trend was observed in the number of live births during COVID 19 compared

to before COVID 19. The highest increase in live births was observed between

month 4 (12.1%; n=2797) and 5 (14.8%; n=3418). However, a slight decrease in

the number of cases between month 5 and 6 (12.8%; n=2960) as well as 7 (14.1%;

n=323) and 8 (12.2%; n=2805). There was no significant evidence that the number

of stillbirths changed before and during COVID-19. However, there was an

increase in the number of stillbirths in the early period between month 4 (12%;

n=55) and 5(15.5%; n=71). Caesarean sections

and Labour complication: An upward trend was observed during COVID-19,

although a slight reduction in the number of labour complications was observed

in months 5(14.2%; n=215), 6(12.9%; n=195), 7 (14.6%; n=220) and 8 (12.9%;

n=195). Further analysis (Table 3) revealed that the number of labour complications

significantly increased (p=0.0003) by 17% during the Covid-19 period. Compared

to the period before COVID-19, higher cases of caesarean section were reported

during COVID 19. There was an increase in the cases between month 4 (10.9%;

n=380), 5(13.3%; n=461), 6 (12.8% n=445) and 7(14.9%; n=516). Incidence Rate

Ratio (IRR) revealed that there was a significant (p <0.001) increase in the

number of caesarean sections by 15% during the Covid-19 period. The

COVID-19 pandemic has led to maternity services adjusting how they provide

antenatal care to pregnant women due to the government restrictions regarding

social distancing, which has impacted on pregnant women’s access to routine

antenatal care [7]. In this study, both the views of the midwifery managers and

findings from the facility records data revealed that COVID-19 has effects on

maternity services and associated outcomes. Though rare, obstetric

complications and outcomes including maternal death, stillbirth, miscarriage,

preeclampsia, foetal growth restriction, coagulopathy, and premature rupture of

membranes among others have been reported among pregnant women during the

COVID-19 pandemic [8]. Increase in neonatal deaths is alluded to reduced

utilization of ANC and Skilled Birth Attendance (SBA) services out of fear of

contracting the dreaded infection in health facilities during the pandemic thus

some women preferred to seek services of the Traditional Birth Attendants

(TBAs). In

addition, a study in London suggests that stillbirths may become more common as

a direct or indirect consequence of the pandemic [9]. This view seems to

support our findings in which there were increase in neonatal deaths and labour

complications during the COVID-19 period. The same is supported by Pallangyo et

al., 2020 [10] when they state that lack of antenatal care has reportedly led

to poor maternal and neonatal outcomes such as ruptured uterus or stillbirth.

In our study, utilization of ANC services was majorly affected during the

COVID-19 period, a finding corroborated by observations in a related study on

effects of COVID-19 on utilization of Antenatal Care services [11, 12]. The

World Health Organization (WHO) appreciates that COVID-19 pandemic may cause

disruptions in the provision of routine immunization services and may in

addition reduce demand for such services (e.g., due to concern about virus

transmission, inconvenience of rescheduled appointments or transportation

barriers). According to the world Health Organization, these challenges may

result in an accumulation of susceptible individuals and ultimately the

resurgence of vaccine-preventable diseases [13]. In our study, the midwifery

managers confirmed that there was in deed disruption of uptake of immunization.

This is similar to a study by Mansour et al., 2021 [14] and Ali, 2020 [15] in

which the same was reported. Evidence show that the deaths prevented by

sustaining routine childhood immunisation in Africa far outweigh the excess

risk of COVID-19 deaths associated with vaccination clinic visits, especially

for the vaccinated children. Outbreaks of vaccine-preventable disease have been

observed during previous interruptions to routine immunisation services, such

as during the 2013-16 Ebola outbreak in west Africa, when most health resources

were shifted towards the Ebola response and decreased vaccination coverage led

to consequent outbreaks of measles and other vaccine-preventable diseases [16]. In

another study conducted to assess the performance of routine immunization,

thirteen of the 15 countries showed a decline in the monthly average number of

vaccine doses provided, with 6 countries having more than 10% decline. Nine

countries had a lower monthly mean of recipients of first dose measles

vaccination in the second quarter of 2020 as compared to the first quarter [17].

According to our findings more mothers feared delivering to the hospitals

leading to almost half being assisted by traditional birth attendants. The

findings are similar to numerous reports that have shown decrease in hospital

deliveries [5,18]. This could be attributed to restricted access to health

facilities as a result of lockdown and curfews that Kenyan government had

imposed to reduce infections. The knock-on effects of the lockdown may mean

that some pregnant women or new mothers were not able to afford to pay for

health care, while others out of fear of either contracting the virus or being

mistaken for a patient seeking COVID-19 care [19]. This

study reveals that more than a third of delivery services were affected during

the pandemic. This could have been necessitated by low activities and

inadequate resources including health workers at the lower tiers hence referrals.

In some instances, maternal and child health clinics might have been converted

into isolation rooms or the facilities suspended altogether. In addition, the

health workers in these facilities might have been infected by COVID-19. For

instance, a maternity wing in the coastal part of Kenya was converted into an

isolation ward and in Mombasa County, maternity and other services were

suspended when Tudor Hospital, a referral health facility, converted into an

isolation centre. Although some healthcare providers had been trained to offer

maternal health services, they lacked Personal Protective Equipment (PPE),

putting themselves and pregnant women and mothers at risk for COVID-19. On 14

July 2020, it was reported that at least 41 employees (19 health care workers

and 22 support staff) at the country's largest maternity hospital had tested

positive for COVID-19 [20]. Our findings also revealed an increase in

unplanned/unintended pregnancies with 90.4% of facility managers confirming

this. This is similar to findings from a related study [21]. The

pandemic has been linked to disrupted uptake of contraceptives which is a

component of maternal health services. During the pandemic, as a result of

restricted movements, community and health facility linkages got disrupted too.

Our findings show that there has been increase in domestic violence during

COVID-19 with 71% of the health workers confirming the position. The findings

are similar to a review by Mittal et al., 2020 [22] found an alarming rise in

the incidents of gender-based violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. A study

done in UK and Kenya also found an increase in patients seeking care for

intimate partner violence three months into lockdown in Kenya [23]. According

to WHO, the high cases of domestic violence could be attributed to stress, loss

of income and isolation [24]. In conclusion, Covid-19 pandemic has been found

to have a cross-cutting effect on utilization of maternity services due to fear

from acquiring infections from hospitals and health care units. The

authors would like to acknowledge the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA),

Kenya office for funding the study. 1. Hegazy AA and Hegazy RA. “COVID-19: Virology, pathogenesis and

potential therapeutics (2020) Afro-Egyptian Journal of Infectious and Endemic

Diseases 1: 93-99. https://doi.org/10.21608/AEJI.2020.93432 2. WHO (2019) Maternal Mortality: Levels and trends

2000-2017. 3. Chersich MF, Gray G, Fairlie L, Eichbaum Q, Mayhew S,

et al. Covid-19 in Africa: Care and protection for frontline healthcare workers

(2020) Global Health 16: 1-6. 4. Kurjak A and Chervenak F. Online Textbook of Perinatal

medicine (3rd Ed.) (2015) New Delhi: The Health Science. 5. Kimani RW, Maina R, Shumba C and Shaibu S. Maternal and

newborn care during the COVID-19 pandemic in Kenya: Re-contextualising the

community midwifery model (2020) Human Resources for Health 18: 3-7. 6. GOK/MOH. Kenya Health sector referral implementation

guidelines 2014 1st edition, 1-44. 7. Esegbona-Adeigbe S. Impact of COVID-19 on antenatal

care provision (2020) Eur J Midwifery 4: 16. https://doi.org/10.18332/ejm/121096 8. Kotlar B, Gerson E, Petrillo S, Langer A and Tiemeier

H. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal health: a

scoping review (2021) Reprod Health 18: 10. 9.

Khalil A, von

Dadelszen P, Draycott T, Ugwumadu A, Pat O Brien, et al. Change in the

incidence of stillbirth and preterm delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic

(2020) JAMA 324: 705-706. 10. Pallangyo E, Nakate MG, Maina R and Fleming V. The

impact of covid-19 on midwives’ practice in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania: A

reflective account (2020) Midwifery 89: 102775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2020.102775 11. Tadesse E. Antenatal care service utilization of

pregnant women attending antenatal care in public hospitals during the COVID-19

pandemic period (2020) Int j wom health 12: 1181-1188. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S287534 12. Temesgen K, Wakgari N, Debelo BT, Tafa B, Alemu G, et

al. Maternal health care services utilization amidst COVID-19 pandemic in West

Shoa zone, central Ethiopia (2021) PLoS One 16: e0249214. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249214 13. WHO (2020) Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Violence against

women. 14. Mansour Z, Arab J, Said R, Rady A, Randa H, et al. Impact

of COVID-19 pandemic on the utilization of routine immunization services in

Lebanon (2021) PLoS ONE, 16: 1-11. 15. Ali I. Impact of COVID-19 on vaccination programs:

adverse or positive? (2020) Hum Vaccin Immunother 16: 2594-2600. 16. Abbas K, Procter SR, van Zandvoort K, Clark A,

Sebastian Funk, et al. Routine childhood immunisation during the COVID-19

pandemic in Africa: a benefit-risk analysis of health benefits versus excess

risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection (2020) Lancet Global Health, 8: e1264-e1272. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30308-9 17. Masresha BG, Luce JR, Shibeshi ME, Ntsama B, Abubacar

ND, et al. The performance of routine immunization in selected African

countries during the first six months of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020) Pan Afr

Med J 37: 1-12. 18. Mwobobia J. The repercussions of COVID-19 fight

Standard Newspaper Kenya (2020) Sect Health Sci. 19. Rodrigues L. Pregnant women in rural kenya are

struggling to access health care amid COVID-19 (2020). 20. Wangamati CK and Sundby J. The ramifications of

COVID-19 on maternal health in Kenya (2020) Sex Reprod Health Matters. https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2020.1804716 21. Hunie Asratie M. Unintended pregnancy during covid-19

pandemic among women attending antenatal care in northwest Ethiopia: magnitude

and associated factors (2021) Int J Womens Health 13: 461-466. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S304540 22. Mittal S and Singh T. Gender-based violence during

covid-19 pandemic: a mini-review (2020) Frontiers in Global Women’s Health. 23. Johnson K, Green L, Volpellier M, Kidenda S, Thomas

MaHale, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on services for people affected by sexual

and gender-based violence. (2020) Int J Gyn Obs 150: 285-287. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13285 24. World Health Organization, RO for E (2020).

Mitigating the impact of COVID-19 on control of vaccine-preventable diseases: a

health risk management approach focused on catch-up vaccination. Amref

International University, Nairobi, Kenya, Tel: +254 (0)723727325, E-mail: Micah.Matiangi@amref.ac.ke

Matiang’i M, Okoro D,

Ngunju P, Oyieke J, Munyalo B, et al. Effects of covid-19 on maternity services

in selected public health facilities from the priority MNCH counties in Kenya (2021)

Nursing and

Health Care 6: 6-10. Covid-19, Maternal, New-born, Child Health,

Pandemic.Effects of COVID-19 on Maternity Services in Selected Public Health Facilities from the Priority MNCH Counties in Kenya

Abstract

Full-Text

Introduction

Methods

Results

Discussion

Acknowledgement

References

Corresponding author

Citation

Keywords