Background

From

the beginning the path to becoming a healthcare professional has always been a

stressful situation. It was stressful getting into the right schools, stressful

getting through all the training, and stressful going out into practice. We all

considered it part of the cost of doing business. The rewards were worth it.

Then several years ago things began to change. Growing bureaucratic intrusions,

changing roles and responsibilities, an intensified focus on cost-efficiency,

productivity, and metric accountability, and the introduction of a number of

different non-clinical tasks including compliance with the electronic medical

record documentation have left staff exhausted and frustrated with a sense of

loss of autonomy and control, and questions about meaning, purpose, and

fulfillment. In 2015 a landmark article published in the Mayo Clinical

Proceedings documented that 50% of physicians reported working under high

stress burnout conditions. This was just the tip of the iceberg. The condition

has been intensified with the Covid-19 pandemic raising new concerns about

practice mechanics. The latest Medscape Annual Survey on Physician Stress and

Burnout continues to show the high degree of stress, burnout, and depression in

physicians. It’s not just physicians. Nurses, Pharmacists, and other paramedical

staff report similar concerns [1-4].

Causes and Consequences

Most of the contributing factors

come from system related issues. More bureaucratic tasks, fulfillment of non-clinical

administrative responsibilities, changing roles, responsibilities, and

priorities, excessive workloads, changes in process flow, greater focus on

productivity, efficiency, and metric accountability, and compliance with

electronic medical input and documentation have all taken their toll. Add on

top of this Covid related issues as to protection, access, and resource

availability have further intensified the problem. For nurses, many of

the stresses are related to scheduling, interactions

with their colleagues, and overall compassion fatigue. All staff can feel

overwhelmed, exhausted, dissatisfied, anxious, and stressed, leading to

physical and emotional distress. Something needs to be done [5].

Barriers

Will anyone ask for help? One of

the first barriers is recognition. Clinical staff have seen a lot and they develop very strong

stoic personalities to deal with day-to-day events. They are willing to

sacrifice their own mind and body for patient care and often don’t recognize

their own symptoms. If they do, the usual response is that they can handle it

by themselves. Afterall, they’ve been under stress all their lives. If they do

want some help, they may not know where to go. If they do consider asking for

outside help, they may be concerned about confidentiality and the associated

stigma of exposure and how others may view their health and competency.

Diagnostic labeling may raise concerns about credentialing and licensure

implications. Barriers are a significant issue that needs to be addressed [6,7].

Solutions

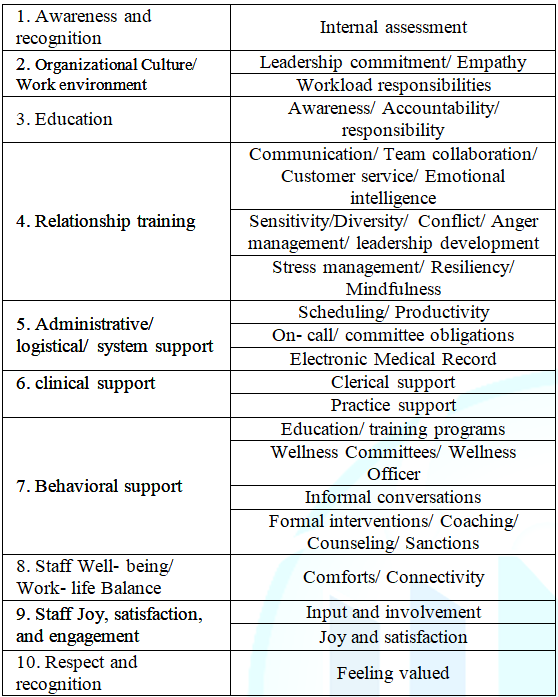

There is no one solution

available to fix the problem. Table 1

gives a list of suggested recommendations. None of these are mutually

exclusive. The importance of each will depend upon work culture and other

specifically identified issues. The first issue is raising awareness. This is a

two-part process involving raising organizational awareness as to the

seriousness of the issue and raising individual awareness as to the importance

of self- recognition, acceptance, and willingness to change. In regard to

assessing the status of the current environment, some insight may come from

listening to hallway gossip, but a more in- depth organizational survey

(examples: Maslach, Mini Z, ProQOL, Well- being Index) will help identify and

quantify specific issues. Next is the importance of culture and work

environment. Those organizations that express concern, empathy, and willingness

to provide resource support to enhance staff well- being have greater success

in managing the attitudes and performance of staff members [8].

Education plays a key role. One

focus is to discuss all the nuances of the current health care environment in a

general session. More comprehensive educational and training programs on a

variety of topics that may include enhancing communication and team

collaboration skills, diversity management, conflict management, anger

management, stress management, mindfulness, and resiliency, will help staff

become better equipped to deal with all the relationship interactions that

impact patient care. The next step is to provide resource support. There are

three areas that need to be addressed. The first is administrative/ logistical

support. As mentioned previously most of the factors influencing stress and

burnout come from a system related focus. Staff are overworked and spending too

much of their time completing non-clinical tasks. Adjusting work schedules, on-

call responsibilities, and committee assignments will help alleviate some of

these pressures. Providing additional training or dedicated staff support

(scribes) will help with concerns about the electronic medical record. Capacity

control and task management are key issues that need to be addressed [9-11].

From a clinical perspective using

PAs, NPs, LVNs, or NAs to handle more routine day to day matters will free up

time for physicians and nurses to focus on more complex patient care matters.

More effective use of designated care coordinators, care navigators, or medical

assistants to help manage logistics of patient care scheduling and follow up

care will also free up time for the clinicians to concentrate on face-to-face

patient activities. The next area is emotional/ behavioral support. Provide

opportunities for discussion. Being able to meet with clinicians, listen to

their concerns, and provide empathetic support goes a long way in improving

their feelings. Some of the training programs discussed earlier can help in

this regard. Some organizations have reinvigorated their Employee Assistance

programs or Wellness Committee to provide skilled personnel to help assist

clinical staff. The use of mentors or coaching programs have been particularly

successful. In rare cases more intense behavioral issues may require

professional counseling and/ or referral to outside services that may impact

staff privileges [12,13].

Maintaining staff well- being is

the number one priority. Always be aware of barriers related to reluctance to

act and provide structure and resources to enhance a positive work life

balance. Provide on- call services such as food, childcare, break rooms,

meditation rooms, and exercise facilities. Encourage opportunities for social

interactions and staff connectivity. Returning the joy and pride to clinical

practice has become a pivotal focus. Giving staff an opportunity to express

their concerns will increase staff involvement and engagement. Reminding staff

about all the good things that only they can do will help them battle

compassion fatigue and increase their levels of joy and satisfaction. Recognizing

their efforts, thanking them for all that they do, and rewarding them for their

efforts will put a smile on their faces [14].

Conclusion

We need to look at all of our

clinical staff as a precious overworked limited resource and do what we can to help

them better adjust to the stress and pressures of today’s healthcare

environment. We can’t leave it up to them to do it on their own. Awareness,

stigma, time, self- sacrifice and dedication to patient care all get in the

way. Stress reduction, relaxation, mindfulness, and resiliency may help but

most of the problems arise from system issues that need to be addressed.

Therefore, we need the organizations to take a more proactive role in helping

out. Showing you care, and implementing services to enhance workplace dynamics

are the key to promoting satisfaction and engagement [15].

References

1. Shanafelt T, Hasan O, Dyrbye L, Sinsky

C, Satele D, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work- life balance

and the general u.s. working population between 2011-2014 (2015) May Clin Proc

90: 1600-1613.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023

3. Medscape Physician 2021 Burnout Report

4. Prasad K,

McLoughlin C, Stillman M, Poplau S, Goelz E, et al. Prevalence and correlates

of stress and burnout among u.s. healthcare workers during the covid-19

pandemic: a national cross-sectional survey (2021) EClinical Medicine 35: 100879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100879

5. Serranno H,

Hassamol H, Dong S and Neeki M. Depression and anxiety prevalence in nursing

staff during the covid-19 pandemic (2012) Nursing Management 52: 24-32.

6. Blum L. Physicians goodness and guilt:

emotional challenges of practicing medicine (2019) JAMA Int Med 175: 607-608.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0428

7. Haque O, Stein M

and Marvit A. Physician, heal thy double stigma- doctors with mental illness

and structural barriers to disclosure (2021) NEJM 384: 885-887.

8. Shanafelt T and Noseworthy J. Executive

leadership and physician well- being: nine organization strategies to promote

engagement and reduce burnout (2017) Mayo Clinic Proc 92: 129-146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004

9. Ameli R, Sinaii N, West C and Luna MJ.

Effect of a brief mindfulness-based program on stress in health care

professionals at a US biomedical research hospital: a randomized clinical trial

(2020) JAMA Network Open 3: e2013424.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.13424

10. Epstein

R and Krasner M. Physician resilience: what it means, why it matters, and how

to promote it (2013) Academic Medicine 88: 301-303. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318280cff0

11. Goroll

A. Addressing burnout: focus on systems not resilience (2020) JAMA Network Open

3: e209514.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.9514

12. Shanafelt T, Stolz

S, Springer J, Murphy D, Bohmanet B, et al. A blueprint for organizational

strategies to promote the well- being of health care professional (2020) NEJM

Catalyst 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.1056/CAT.20.0266

13.

Dyrbye L,

Shanafelt T, Gill P and Satele D. effect of a professional coaching

intervention on the well- being and distress of physicians: a pilot randomized

clinical trial (2019) JAMA Int Med 179: 1406-1414.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.2425

14. Dugdale L.

Re-Enchanting medicine (2017) JAMA Int Med 177: 1075-1076. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.2413

15. Rosenstein A.

Hospital administration response to physician stress and burnout (2019)

Hospital Practice.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/21548331.2019.1688596

Corresponding author

Alan H Rosenstein, Practicing Internist, Consultant in Physician Behavioral Management, San Francisco, California, USA, Tel: +415 370 7754, E-mail: ahrosensteinmd@aol.com

Citation

Rosenstein HA. Organizational

vs individual efforts to help manage stress and burnout in healthcare

professionals (2021) Nursing and Health Care 6: 11-13.

Keywords

Stress

and burnout, Resilience, Organizational culture.

PDF

PDF