Research Article :

Objective: In the study, it was

aimed to determine the risk and level of knowledge of individuals who applied

to the clinic for dental treatment. Methods:

The research consisted of 713 adult individuals who went to the dental clinic

for dental treatment between 01 March and 31 August 2020, who were willing to

participate in the study and who met the inclusion criteria. The questionnaires

developed by the researchers were used to determine the risks of developing

infective endocarditis, and the knowledge levels of Oral and Dental Health and

Infective Endocarditis in individuals who attended dental treatment.

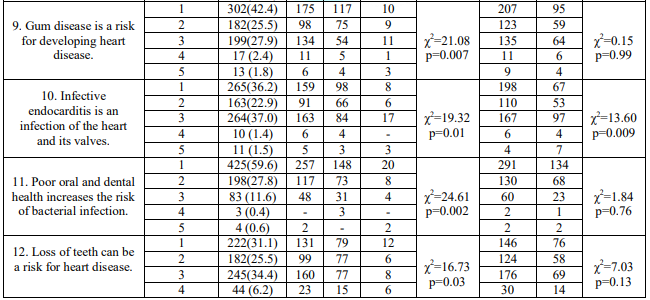

Descriptive statistical analyzes were made. Results: In the study, the rate of agreeing that "oral and

dental health problems are as important as other health problems" (p =

0.005) and that "infective endocarditis disease is an infection of the

heart and its valves" (p = 0.009) was found to be significantly higher in

females than males. It was determined that the majority of the individuals

(38.7%) were indecisive about the idea that “antibiotics should be used before

dental treatment”. When the infective endocarditis risk factors were evaluated

in the study, it was found that 8.1% had piersing in their body, 28.3% had

problems such as gingivitis, bleeding and swelling. Conclusion: The most important issue in preventing the development

of infective endocarditis is to increase the awareness of individuals. The

society should be made aware of the risk factors that may cause infective

endocarditis and their knowledge level should be increased. Infective

Endocarditis (IE) is a microbial infection of the endocardial surface of the

heart, usually caused by gram-positive cocci. Although valves are mostly

involved, the disease also occurs in other parts of the endocardium,

ventricular septal defect surface and chordae tendinea. The prolongation of

life causes degenerative-atherosclerotic valve disease and prosthetic valves to

become widespread and increase the frequency of exposure of patients to

nosocomial infections. Therefore, the incidence of IE is gradually increasing.

More than 50% of elderly individuals have calcified aortic stenosis. Fever is

less common and anemia is more common in elderly individuals, especially

because of the high rate of IE due to S. bovis, where chronic lesions are

common and can cause occult bleeding. Older age has been associated with a poor

prognosis in most recent studies. As new social factors, the increase in the

use of intravenous drugs and piersings also contributes to the increased

incidence of IE in young adults. Body piersings are popular and are becoming a

major problem in young adults. Implanted devices (implanted cardioverter

defibrillator ICD, pacemaker insertion) can cause damage to the endocardium. In

addition, the risk of IE is very high in individuals undergoing hemodialysis. The

incidence of IE during pregnancy has been reported to be very low (0.006%).

However, pregnant women with unexplained fever and heart murmur should be

evaluated [1-3]. The most important risk

factor in infective endocarditis is pre-existing heart damage. Lesions occur in

deformed and artificial valves. Other conditions that increase the incidence of

infective endocarditis include poor oral and dental hygiene, prolonged

hemodialysis and diabetes mellitus. Other important risk factors of subacute

infective endocarditis are dental treatment, invasive procedures and infections

[1]. Bacteremia can also be observed in patients with poor dental health,

regardless of dental interventions, and post-intervention bacteremia rates are

higher in this patient group. These findings emphasize the importance of good

oral hygiene and regular dental examination in the prevention of IE [3]. The

presence of rheumatic valve disease in developing countries still maintains its

importance in terms of the risk of endocarditis, although the risk of IE is now

less than 20% [1]. As a result of the prolongation of life expectancy and the

increase in the geriatric population in developed countries, mostly calcific

valve lesions occur on the basis of infective endocarditis [2]. There

is a strong relationship between bacteremia incidence of infective endocarditis

bacteria and poor oral hygiene and gum disease. American Heart Association

(AHA) guidelines have long emphasized the importance of oral health in

preventing infective endocarditis, emphasizing the importance of focusing on

prevention of dental and gum disease for individuals at risk of infective

endocarditis, and the provision of routine dental care and oral and dental

health [4]. Prevention of infective endocarditis is vital in susceptible

individuals. Individuals with known heart disease or specific risk factors such

as murmur should be informed about the precautions to be taken. The possibility

of recurrence of infective endocarditis is also very high. For this reason, it

is important to inform individuals about this issue as well. Oral and dental

care should be regularly performed and controlled by the dentist in individuals

with high and moderate risk for infective endocarditis [1]. For this reason, it

is of primary importance to determine the risk factors and knowledge levels of

individuals about infective endocarditis and to direct them correctly. There

are quite a few studies showing the determination of individuals who apply to

the clinic for dental treatment in terms of infective endocarditis risk and the

measurement of the knowledge levels of patients. Especially in the literature,

it is very difficult to reach studies that question the level of knowledge of

individuals in terms of infective endocarditis risk. Therefore, in this study,

it was aimed to determine the risk and level of knowledge of individuals who

applied to the clinic for dental treatment. Purpose and type

of the research:

It was planned and implemented as a descriptive study to determine the risk of

developing infective endocarditis and their level of knowledge about infective

endocarditis of individuals who applied to the clinic for dental treatment. In

the study, "What are the knowledge levels of individuals applying for

dental treatment about infective endocarditis?" and "What are the

risks of developing infective endocarditis of individuals who apply for dental

treatment?" answers were sought. Research Sample: The universe of

the study consisted of individuals who were informed about the purpose of the

research and the expectations from the research and who were willing to

participate in the study, who went to the dental clinic for dental treatment

between March 01 and August 31, 2020. When the sample was calculated according

to the population of the study, it was calculated that 260 individuals should

be interviewed by calculating with 5% margin of error at 95% confidence

interval. The sample of the study consisted of 713 adult individuals who came

to the dental clinic, met the inclusion criteria and were willing to

participate in the study, in line with the purpose of the study. Individuals

aged 18 and over who agreed to participate in the study were included in the

study. Individuals who were not willing to participate in the study, who used narcotic

analgesics at a level that would affect their perception of questions and

communication, and who were diagnosed with severe mental disease and cognitive

dysfunction were not included in the study. Data Collection

Tools: The

form, which was created by the researchers by reviewing the literatüre [1-5],

evaluating the sociodemographic characteristics of the individuals and their

status related to dental treatment and cardiovascular disease (19 items) was

used to collect data. The study also used a questionnaire to determine the

presence of infective endocarditis signs and symptoms (11 items; yes, no;

2-point Likert type), the risk of developing infective endocarditis (20 items;

yes, no; 2-point Likert type), and the level of knowledge of Oral Dental Health

and Infective Endocarditis (17 items; strongly disagree, disagree, undecided,

agree, strongly agree; 5-point likert type) created by the researchers in

accordance with the literatüre [5-10]. The questionnaire used in the study

consists of 67 items in total. Statistical

Analysis: All

analyzes were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS)

21 software program (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Significance value was

accepted as p <0.05. In the study, descriptive statistical analyzes were

performed to evaluate the sociodemographic characteristics and disease

information of the individuals, the oral health of the individuals who applied

for dental treatment and the knowledge levels of infective endocarditis, signs

and symptoms of infective endocarditis, and infective endocarditis risk

factors. Ethical Issues: The necessary

institutional permission and ethical permission from a state university ethics

committee (with the decision numbered 2019/177) was obtained for the study to be

carried out in the dental clinic between March 1 and August 31, 2020. Patients

invited to the study were included in the study after being informed verbally

about the purpose and expectations of the study in accordance with the

Declaration of Helsinki, and after obtaining verbal and written consent that

they were willing to participate in the study.Determination of Infective Endocarditis Development Risks and Knowledge Levels of Individuals Applying for Dental Treatment

Hilal Uysal

and Iremnur Emir

Abstract

Full-Text

Introduction

Methodology

Results

A

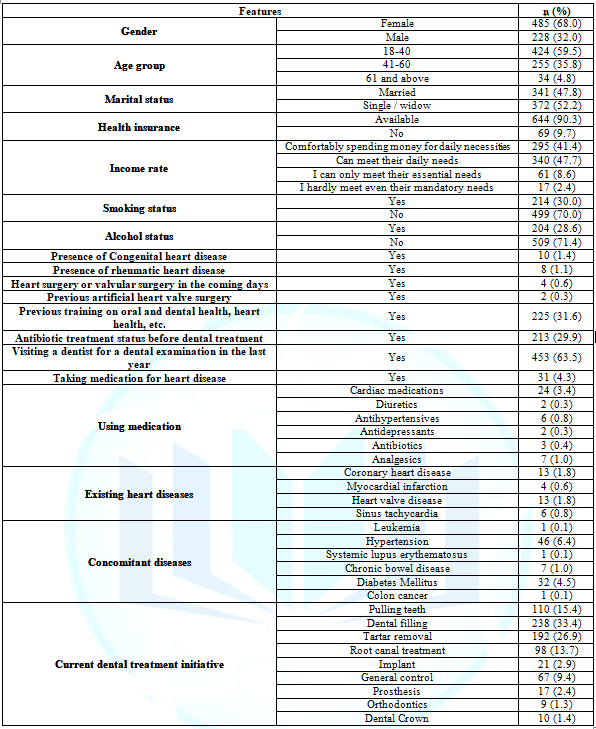

total of 713 individuals, 68% female, 32% male, were included in the study. In

the study, it was determined that 63.5% of them "went to the dentist for a

dental examination in the last year", 29.9% of them "received

antibiotic treatment by the dentist before dental treatment" (Table 1). When

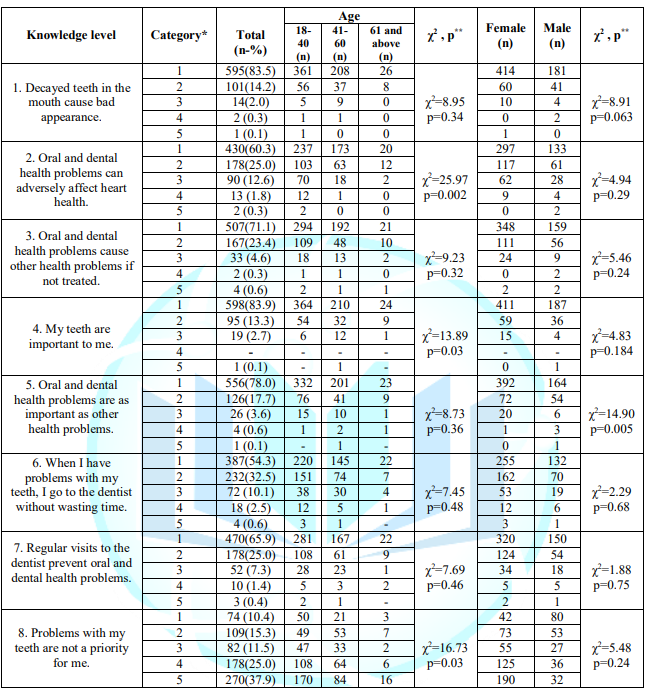

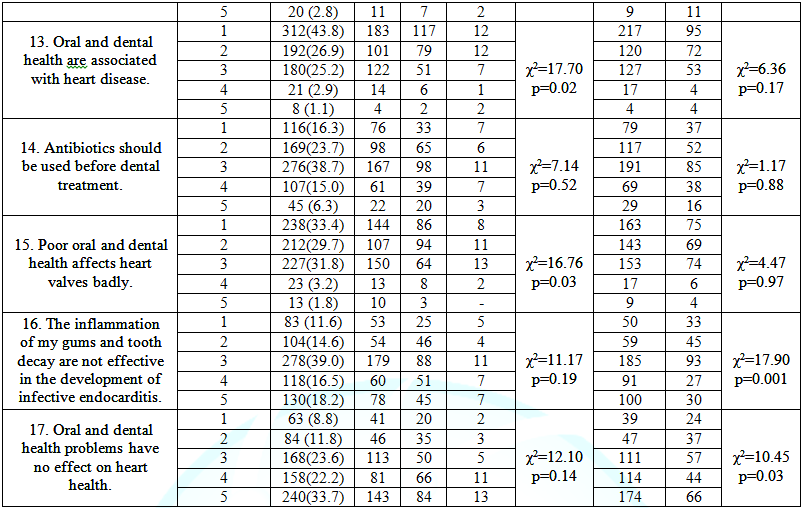

the oral and dental health and infective endocarditis knowledge levels of the

individuals included in the study were evaluated, it was found that the rate of

agreeing that "oral and dental health problems are as important as other

health problems" was found to be significantly higher in females than

males (p = 0.005). In addition, it was found that the status of participating

in “infective endocarditis disease is an infection of the heart and its valves”

was significantly higher in females than males (p = 0.009) (Table 2). It was

determined that women who absolutely disagree with the statement “Inflammation

in my gums and tooth decays are not effective in the development of infective

endocarditis (p = 0.001)” and “Oral and dental health problems have no effect

on heart health (p = 0.03)” were found to be higher than men. Generally, it was

determined that 39% of the individuals were indecisive, 11.6% and 14.6% of them

definitely agreed and agreed with the statement "Having inflammation in my

gums and caries in my teeth is not effective in the development of infective

endocarditis" (Table 2).

However,

when the individuals agreeing with the statement "Antibiotics should be

used before dental treatment" was examined, it was determined that the

majority of the individuals agreed and agreed with this idea (respectively

16.3%; 23.7%), and 38.7% were undecided. In addition, 15% of the individuals

stated that they did not participate either. Similarly, it was found that

individuals strongly agreed and agreed with the statement "poor oral and

dental health affects heart valves badly" (respectively 33.4%; 29.7%,),

but it was found to be higher in unstable (31.8%) (Table 2). In the study,

18-40 age group compared to other age groups "Oral and dental health

problems can affect heart health badly (p = 0.002)", "My teeth are

important to me" (p = 0.03), "Gum disease is a risk for

developing heart disease (p = 0.03). = 0.007)", "Poor oral and dental

health increases the risk of bacterial infection (p = 0.002)", "Heart

disease is associated with oral and dental health (p = 0.02)", "Poor

oral and dental health affects heart valves badly (p = 0.03)” expressions

stated that they

strongly agree. In addition, it was determined that the 18-40 age group did not

agree with the fact that their problems with their teeth were not a priority

for them (p = 0.03).

It was determined that the majority of those who definitely agreed with the

statement “Infective endocarditis is the infection of the heart and its valves”

were from the 18-40 age group, however, those who were undecided on this issue

were mostly the 18-40 age group (p = 0.01) (Table 2).

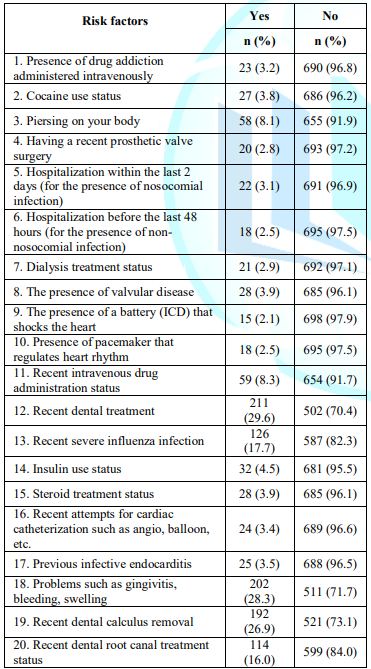

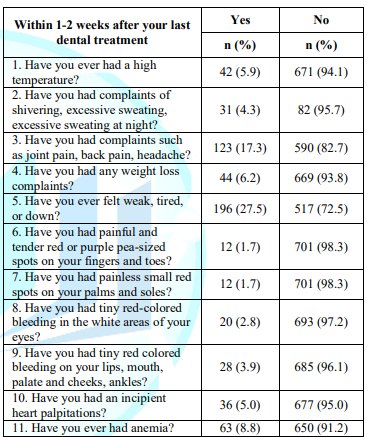

In this section, the risk factors of individuals participating in the study for developing infective endocarditis were evaluated. In this research, 3.2% of the individuals were drug addicted intravenously, 3.8% had cocaine use, 8.1% had piersing in their body, 2.8% had a recent prosthetic heart valve surgery, 3.1% in the last 2 days 2.5% were hospitalized in the last 48 hours, 2.9% received dialysis treatment, 3.9% had valvular disease, 2.1% had ICD, 2.5% had pacemaker, 28.3% had gingivitis, bleeding 26.9% of them had recently had dental calculus cleaning, and 16% had recently undergone root canal treatment (Table 3). It was determined that 5.9% of the individuals had very high fever, 17.3% had joint, back and headache complaints, 27.5% felt weak and malaise, 2.8% of them have tiny red-colored bleeding in the white areas of their eyes, 3.9% had tiny red-colored bleeding on their lips, mouth, palate and cheeks, ankles, 5% had new-onset heart palpitations, and 8.8% of individuals had anemia within 1-2 weeks after the last dental treatment (Table 4).

Table 1: Sociodemographic Characteristics and Distribution of Disease Information (N=713).

In the study, it was aimed to determine the risk of developing infective endocarditis and their level of knowledge about infective endocarditis of individuals who applied to the clinic for dental treatment. Of the individuals participating in the study, 32% were men, 68% were women, 59.5% were 18-40 years olds, 35.8% were 41-60 years old, 4.8% were 61 years old and over and 30% smoked was detected (Table 1). Smoking is an important risk factor for both cardiovascular disorders and oral health.Smoking is known to cause endothelial dysfunction [11]. Studies have shown that smoking increases the frequency and severity of periodontal disease [12]. Although it increases plaque and stone build-up and aggravates disease progression in smokers, there are fewer clinical and gingivitis symptoms, and it has been reported that this is due to smoking masking gingivitis [13]. Infective endocarditis is a serious infection of the endocardial surface of the heart and its valves and is associated with high morbidity and mortality. It has been reported that infective endocarditis most frequently develops in patients with congenital heart disease, prosthetic heart valve and infective endocarditis [14]. In this study, it was determined that 1.4% of individuals had congenital heart disease, 1.1% had rheumatic heart disease, 0.3% had previous artificial heart valve surgery (Table 1).In the study, it was found that 29.9% of the individuals were given antibiotic treatment by the physician before dental treatment (Table 1). In addition, it was determined in the study that 16.3% of the individuals definitely agreed that antibiotics should be used before dental treatment, and 23.7% agreed (Table 2). European Society of Cardiology guidelines recommend antibiotic prophylaxis in various dental procedures for patients at high risk of infective endocarditis. However, it is also stated that unnecessary use of antibiotics may cause the development of antibiotic resistance of microorganisms and anaphylactic reactions during dental procedures [15]. For this reason, antibiotic prophylaxis is quite limited in the guidelines, and it is emphasized that good oral hygiene and regular dentist controls are more important than prophylaxis in order to prevent IE [16]. It has been noted that there is an increase in the high-risk population susceptible to IE, such as procedures resulting in bacteremia, the elderly, patients with diabetes mellitus, renal failure, chronic dialysis, and those with intra-cardiac prosthetic devices [17]. In the study, it was found that 4.5% of the individuals were diagnosed with diabetes, 6.4% with hypertension, and 1.8% with coronary heart disease (Table 1).

Table 3: Distribution of Individuals for Infective Endocarditis Risk Factors (N=713).

Infective endocarditis is usually

caused by bacterial, which is the result of invasive dental treatments. Studies

have shown that even ordinary daily activities such as tooth brushing and

chewing gum cause low and continuous bacteremia. If the patient's oral hygiene

is poor, bacteremia caused by daily activities such as tooth brushing carries a

higher risk of IE than bacteremia that occurs during dental treatment [16].

Bacteremia can be caused by invasive dental procedures such as chewing,

brushing teeth, using dental floss, tooth extraction or periodontal treatment.

Inflammatory markers can be produced locally in the oral cavity and released

into the bloodstream [11]. In a study, it was found that patients diagnosed

with infective endocarditis had tooth extraction (2.7%), surgical intervention

(0.8%), calculus removal (3.9%), periodontal treatment (2.4%) and endodontic

treatment (% 2.4) within 12 weeks before hospitalization [18]. In this study,

when the risks of developing infective endocarditis were evaluated, the reasons

for applying to the dental clinic were tooth extraction (15.4%), dental filling

(33.4%), tartar removal (26.9%), root canal treatment (13.7%), implant (2.9%). (Table

1).

Table 4: Distribution of Infective Endocarditis Signs and Symptoms of Individuals (N=713).

Infective endocarditis is a

disease caused by a bacteremia that affects different organs or tissues,

including the oral cavity. Although it has a low incidence, it can pose a

potential threat to the life of the affected individual. It predominantly tends

to develop on previously damaged heart valves, the most common location being

the mitral valve, followed by the aorta and, in rare cases, the pulmonary valve

[19]. It has been reported that patients with prosthetic valves or prosthetic

materials used for cardiac valve repair, those with a history of IE and

congenital heart disease are at the highest risk of infective endocarditis.

Risky dental procedures include dental procedures in which the gingiva or

periapical area of the tooth is manipulated, or perforation in the oral mucosa

(including tartar removal and root canal attempts) [15].

Periodontitis contributes to the

global burden of chronic oral diseases and is a major public health problem

worldwide. It is a bacterial infection that causes dental plaque development

and tooth loss [10]. Periodontitis has been associated with impaired

cardiovascular health, endothelial dysfunction, and atherosclerosis [11]. When

the risk factors for developing infective endocarditis were evaluated, 29.6% of

the individuals had a recent dental treatment and 17.7% had severe flu

infection, 28.3% had problems such as gingivitis, bleeding, swelling, and 26.9%

had a recent tartar removal, 16% had recently undergone dental root treatment,

8.3% had a recent vascular drug application, 8.1% had piersing in their body,

2.1% had an ICD and 2.5% one of them was found to have a pacemaker (Table 3).

Strom, et al., (2000) in their

study, found an increased risk of IE in toothless cases infected with dental

flora, and stated that they found a risk reduction among those who use dental

floss daily[20]. This result suggests that oral hygiene practices are

beneficial, especially for those with high risk of IE. Peter, et al., (2009)

found that oral hygiene and gum disease indices were significantly associated

with bacteremia associated with IE after tooth brushing. They stated that when

the plaque and tartar scores were examined, the participants were at increased

risk of bacteremia. It has been reported that bleeding after tooth brushing

increases the risk of developing bacteremia approximately eight times. The risk

of bacteremia after tooth brushing has been found to be associated with poor

oral hygiene and bleeding gums after tooth brushing. It has been reported that

provision and maintaining oral hygiene can reduce the risk of developing IE

[21].

In this study, it was found that the majority

of those who agreed that gum disease is a risk for developing heart disease

(Table 2). However, it was determined that there was a majority (39%) of those

who were hesitant to agree that inflammation of the gums and tooth decay were

not effective in the development of infective endocarditis. It was determined

that there were those who absolutely did not agree with the statement that oral

and dental health problems had no effect on heart health (33.7%) and the

majority (43.8%) definitely agreed that heart disease and oral-dental health

were related. Those who definitely agree that infective endocarditis is an

infection of the heart and its valves (36.2%) and those who were undecided

(37%) were in the majority (Table 2).

Improving oral health is

essential in patients at risk of endocarditis. This is the best way to reduce

the need for surgery in these patients. However, this aspect of dental

treatment is often neglected and a high percentage of patients in the

cardiology clinic suffer from a periodontal disease. In addition, there is no

reliable evidence that oral hygiene methods such as electric toothbrushes,

irrigators, or other similar devices can pose a health risk [19]. While oral

health is so important, it is striking that individuals stated in the study

that problems with their teeth are not important (10.4%; 15.3%) (Table 2). Considering

the possibility of recurrence of infective endocarditis and the high risk of

mortality if it is not detected and treated early, it is important to determine

the level of knowledge of individuals about infective endocarditis and to

reveal risk factors. When the literature is examined, it has been found that

epidomiological studies investigating the relationship between periodontal

disease and cardiovascular diseases, studies in which the level of knowledge of

dentists on antibiotic prophylaxis are determined, and studies evaluating the

knowledge level of the families of children with congenital diseases have been

found. However, it has been found that the studies in which the knowledge

levels of individuals about oral health are determined are very limited. In a

systematic review, it was reported that the protection of oral health in

cardiovascular diseases is important, however, it was neglected during cardiac

care [22].

There is no study in which the

level of knowledge, especially about the development of infective endocarditis,

risk factors and symptoms are determined. However, it will be an important

public health initiative to determine the infective endocarditis symptom

findings, risk factors, and the level of knowledge of individuals about

infective endocarditis in order to raise awareness and to disseminate such studies.

It is reported that very few individuals with cardiovascular disease go to the

dentist for dental care despite having dental problems. The reason for this is

seen as the lack of oral health awareness. In the guidelines, it is recommended

to recognize the relationship between periodontal disease and cardiovascular

disease, and to implement treatment and preventive approaches to reduce the

risk of primary and secondary cardiovascular disease. The international general

view is that all cardiovascular patients should receive oral health education

on the importance of oral health [22]. In a study of individuals with

cardiovascular heart disease, it was reported that they had high awareness of

the need for regular dentist visits when they had heart disease, regular

flossing, and common symptoms of gum disease (loose teeth, bad breath) (68-75%

correct answers). Areas of poor knowledge have been reported to be about

cardiac medications causing dry mouth and the effect of this condition on

overgrowth of the gum, the association between poor oral health and an existing

cardiac condition (12-53% correct response) [10]. The individuals participating

in this study also stated that they agreed that going to the dentist regularly

would prevent oral and dental health problems (65.9%) and that they went to the

dentist immediately (54.3%) when they had problems with their teeth (Table 2).

In a study that investigated the

infective endocarditis awareness levels of the parents of children with

congenital heart disease, which is one of the few studies about IE in the

literature, it was found that 64.8% of the parents knew that there was a

relationship between oral hygiene and endocarditis, and 35.2% did not. In the

same study, it was stated that 31% of the parents knew about prophylaxis before

the procedure, while 69% did not. In the study, although the awareness of

parents about oral-dental health and heart relationship was moderate, the level

of awareness about endocarditis and pre-procedure prophylaxis was found to be low

[16]. Da Silva, et al., (2002), in a study they applied to the families of 104

children between the ages of 2 and 17 with the risk of IE, 9.6% of the families

knew the meaning of IE, 60.6% of them are knowledgeable about heart problems

that may be experienced after oral treatment procedures, 72.1% of them stated

that they were aware of the necessity of antibiotic use before the oral treatment

procedures [23].

Smith and Adams (1993) stated in

their study that the rate of families who knew the meaning of IE was 42.3%.

Also, in the same study, 76.9% of the families reported that they were

conscious of the necessity of antibiotic use before oral treatment procedures,

and that 41.3% of the families saw good oral hygiene as a precaution against

the risk of infection [24]. In a study evaluating the level of knowledge of the

families of children with congenital heart disease about infective

endocarditis, it was determined that the knowledge of the families about

endocarditis and its prevention was insufficient. It was determined that only

16.7% of the families interviewed gave the correct answer to the question of

what is endocarditis. He stated that only 43.3% of the families could count the

dental procedures and 56.7% of them could not answer at all when asked about

the risk procedures for the development of IE. In the same study, 55.6% of

families stated that they received information about oral hygiene care. 1.1% of the families stated that they do not

know the name of the drugs given before dental treatment. The authors stated

that families neglect oral and dental care because they have cardiac and

respiratory diseases [25]. In another study, the majority of individuals

(83.4%) stated that their dental health is more important than their general

health. 41.1% of the families stated that they do not know the name of the

drugs given before dental treatment.

The authors stated that families

neglect oral and dental care because they have cardiac and respiratory diseases

[25]. In another study, the majority of individuals (83.4%) stated that their

dental health is more important than their general health. Most participants

reported that they cleaned their teeth or prostheses two or more times a day

(60.4%). It was stated that the majority of individuals (90.9%) used fluoride

toothpaste, only one third (34.6%) used dental floss or other aids to clean

between their teeth. In the same study, more than half of the individuals

reported that they went to the dentist once in the last 12 months (58.8%) and

more than a quarter of the individuals went to the dentist more than two years

ago [10]. In this study, it was determined that the number of people who went

to a dentist for dental examination in the last year was 63.5% (Table 1). It is

seen that the number of those who do not go to the dentist for dental care and

control, but only when there is a problem, is also substantial. Sanchez, et

al., (2019) stated that only 10.7% of the individuals who participated in their

research received any information after their cardiac diagnosis, while less

than half (40.6% n = 13) of all participants with valvular disease (n = 32)

reported that they received any oral health information. However, they were

generally more likely to receive information than those with other

cardiovascular disorders (40.6% vs 7.4%, p <0.001). It was found that less than half of the

participants received information even in the patients with valve disease that

had to be cleaned before the surgery. In this study, 31.6% of the individuals

reported that they had received training on oral and dental health and heart

health (Table 1).

Studies have shown that good oral hygiene and

gum health are factors that reduce the risk of developing infective

endocarditis [21]. Oral infections, especially periodontal disease, increase

the level of systemic inflammation and worsen systemic diseases such as

diabetes, respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis [26].

Nguyeni et al., (2020) [26] found that 33% of individuals go to the dentist

every 6 months, 33% go to the dentist every 12 months, 21% every 12-18 months,

and 12% only go to the dentist if there is pain.

Limitations of

the Study

Studies evaluating the level of

knowledge about infective endocarditis were very insufficient. Therefore, the

discussion was conducted with a limited resource. Since the COVID-19 pandemic

was declared after our data collection process for the research started, there

were problems in the data collection process. We would like to state that our

meeting with individuals is limited, especially due to pandemic limitations in

dental clinics, and this is reflected in the number of samples.

Conclusion and

Suggestions

As a result; It was determined

that the rate of participation of the individuals participating in the study

was high because oral and dental health problems could cause other health

problems. However, it was found that infective endocarditis disease of the

individuals was an infection of the heart and valves, and those who did not

know that the loss of teeth could be associated with the development of heart

disease were found to be at a considerable level. In addition, it is seen that

there is a high rate of those who think that antibiotics should be used before

dental treatment. The most important issue in preventing the development of

infective endocarditis is to increase the awareness of individuals. It is

necessary to raise awareness of the risk factors that may cause infective

endocarditis in the society.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the staff of the dental clinics for whom we collected

data in the study and the patients who agreed to participate in the study.

1. Enç

N and Uysal H. Internal Medicine Nursing, In: Infectious diseases of the heart

(2020) 2nd Edition, Istanbul: Nobel tıp kitabevleri, 109-119.

2. Uysal

H. Internal medicine nursing with case scenarios (Özer S edt.) In: Infective

diseases and care management (2019) 1st Edition, Istanbul: İstanbul Tıp Kitabevleri,

179-187.

3. Habib

G, Hoen B, Tornos P, Thuny F, Prendergast B, et al. Infective endocarditis

diagnosis, prevention and treatment guideline (2009 update) European Society of

Cardiology (ESC) Infective Endocarditis Diagnosis, Prevention and Treatment

Task Force (2009) Eur Heart J 30: 2369-2413.

https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehp285

4. Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, Fowler Jr VG, Tleyjeh IM., et al. Infective Endocarditis in Adults: Diagnosis,

Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications. A Scientific Statement

for Healthcare Professionals from the American Heart Association (2015) Circulation 132: 1435-1486. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000296

5. Sanchez P, Everett B, Salamonson Y, Ajwani S, Bhole S, et al. Perceptions of cardiac care

providers towards oral health promotionin Australia (2018) Collegian 25: 471-478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2017.11.006

6. Najafipour H, Mohammadi TM,

Rahim F, Haghdoost AK, Shadkam M. Association of Oral Health and Cardiovascular

Disease Risk Factors ‘‘Results from a Community Based Study on 5900 Adult

Subjects (2013) ISRN Cardiol 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/782126

7. Meurman JH, Sanz M and Janket SJ.

Oral Health, Atherosclerosis, And Cardiovascular Disease (2004) Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 15: 403-413. https://doi.org/10.1177/154411130401500606

8. Sanchez P, Everett B, SalamonsonnY, Ajwani S,

Bhole S, et al.

Oral health and cardiovascular care: Perceptions of people with cardiovascular

disease (2017) PLoSONE 12 : e0181189.

9. Lee

H, Kim HL, Jin KN, Oh S, Sohee Oh, et al. Association between Dental Health and

Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease: An Observational Study (2019) BMC

Cardiovascular Disorders 19: 98.

10. Sanchez P, Everett B, Salamonson Y, Redfern J, Ajwani S, et al. The oral health status, behaviours and knowledge of patients with cardiovascular disease in Sydney Australia: a cross-sectional survey (2019) BMC Oral Health 19: 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-018-0697-x

11.

Mozos

I and Stoian D. Oral Health and Cardiovascular Disorders. In: Understanding the

Molecular Crosstalk in Biological Processes. Oral Health and Cardiovascular

Disorders (2019) Intech Open. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.85708

12. Dhotre

SV, Davane MS and Nagoba BS. Periodontitis, Bacteremia and Infective

Endocarditis: A Review Study. (2017) Arch Pediatr Infect Dis 5: e41067. https://dx.doi.org/10.5812/pedinfect.41067

13.

Nociti

FH, Casati MZ and Duarte PM. Current perspective of the impact of smoking on

the progression and treatment of periodontitis. (2015) Periodontol 2000 67: 187-210. https://doi.org/10.1111/prd.12063

14.

Karadağ YF, Yavuz SS, Aydın CG, Tigen ET, Sırmatel

F, et al Assessment of the Knowledge and Awareness Levels of Dentists Regarding

Prophylaxis for Infective Endocarditis (2019) Medeniyet Med J 34: 39-46. https://doi.org/10.5222/MMJ.2019.76736

15.

Habib

G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, Bongiorni MG, Casalta JP, et al 2015 ESC

Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis. The Task Force for the

Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology

(ESC) Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS),

the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM) (2015) Eur Heart J 36:

3075-3123. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319

16.

Yılmaz M, Serin AB, Özyurt A, Karpuz D and Hallıoğlu

O. Determination

of oral-dental health status in children with heart disease and level of

awareness of infective endocarditis in their parents (2020) Mersin

Univ Heal Sci J 13: 117-125. https://doi.org/10.26559/mersinsbd.648783

17. Robinson AN and Tambyah PA. Infective endocarditis- An

update for dental surgeons (2017) Singapore Dental Journal 38: 2-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sdj.2017.09.001

18. Chen PC, Tung YC, Wu PW, Wu LS, Lin YS, et al. Dental

Procedures and the Risk of Infective Endocarditis (2015) Medicine 94: 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000001826

19. Mang-de la Rosa MR., Castellanos-Cosano L, Romero-Perez, MJ and

Cutando

A. The bacteremia of dental origin and its implications in

the appearance of bacterial endocarditis. (2014) Med

Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 19: e67–e73. http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.4317/medoral.19562

20. Strom BL, Abrutyn E, Berlin JA, Kinman JL, Feldman RS, et

al. Risk Factors for Infective

Endocarditis, Oral Hygiene and Nondental Exposures (2000) Circulation 102: 2842-2848. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.102.23.2842

21. Lockhart PB, Brennan MT, Thornhill M, Michalowicz B, Noll J, et al.Poor oral hygiene

as a risk factor for infective endocarditis-related bacteremia J Am Dent Assoc 140: 1238-44. https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.2009.0046

22. Sanchez P, Everett B, Salamonson Y, Ajwani S and George

A. Oral Healthcare and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scoping Review of Current

Strategies and Implications for Nurses. (2017) J Cardio Nurs 32: E10-E20. https://doi.org/10.1097/jcn.0000000000000388

23. Da Silva D, Souza IPR and Cunha M. Knowledge, attitudes

and status of oral health in children at risk for infective endocarditis (2002)

Int J paediatric dentistry 12: 124-131.

https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-263x.2002.00335.x

24. Smith A and Adams D. The dental status and attitudes of

patients at risk from infective endocarditis (1993) BDJ 174: 59. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4808078

25.

Haag F, Casonato S, Varela F and Firpo C. Parents’ knowledge of infective

endocarditis in children with congenital heart disease (2011) Rev Bras Cir

Cardiovasc 26: 413-418.

26. Nguyen JG, Nanayakkara S and

Holden ACL. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practice Behaviour of Midwives Concerning

Periodontal Health of Pregnant Patients (2020) Int J Environ Res Public Health 17:

2246-2264. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17072246

Risk factors, cardiovascular disease,

endocarditis, heart valve diseases, oral health.