Introduction

World

is currently going through a major pandemic of corona virus. New CoV infection

epidemic started in Wuhan, China in late 2019. First it was called as 2019-nCoV

and later renamed by WHO as COVID-19

on 11th February, 2020 [1]. WHO in March 2020 declared the outbreak

as pandemic

[2]. Considering challenges when comparing data across nations, COVID-19

mortality in some countries is significantly higher than in others.

Several

factors may play a role in this discrepancy, including disparities in the

proportion of the elderly in a community, general health, health care

accessibility and efficiency and socio-economic status. Structural, COVID-19 is

a ~350 kilobase-pair (kbp) enveloped ss-RNA virus [3]. A possible route of

transmission between humans is by airborne droplets, touching or bringing into

contact with an infected person or a contaminated surface. In addition, other

routes such as blood or saliva have not been explored, but are possible due to

documented blood-borne

infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS, hepatitis C

and hepatitis B viruses. These trading volumes express concern about a similar

transmission route for COVID-19 in dental settlement.

According

to the WHO situation report 158 (26th June 2020) update on COVID-19,

there have been more than 9,473,214 reported cases and 484,249 deaths worldwide

[4]. By imposing a nationwide lockdown, India has curtailed the spread of this

virus to a certain extent; however, the total number of reported cases has

crossed 490,401 with approximately 15301 deaths and these numbers continue to

rise and approx 864 confirmed cases in Himachal Pradesh with 349 active cases

while around 494 recovered also (Figure

1)[4,5].

Figure 1: Himachal

Pradesh COVID-19 update of June 2020.

According

to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), Dental

Health Care Professionals (DHCP) is put in a very high

risk category because dentists work near to the oral cavity of the patient [6].

Dental clinics across the country have been shut for over two months. With the

pandemic still on the growth curve, there is no hope of revival anytime soon,

compounded by zero earnings by dental practitioners and staff at some clinics.

Dental treatments include the use of rotary instruments, such as handpieces and

scalers, which produce aerosols. Therefore, a greater understanding of the

virus structure, transmission modes, clinical characteristics, and testing

methods is required that can help shape protocols for dental practices to

distinguish cases and avoid further spread of infection to patients and to

DHCP. Under these conditions, it may be common for dentists to develop a fear

that their patients if exposed to virus may infect them too.

Fear

and anxiety are emotional responses that can be correlated by social, digital,

and mass media with the growing coverage on the COVID-19 pandemic. Mild anxiety

is normal and encourages actions in a protective and healthy manner [7].

Considering the current rapid spread of infection, the Ministry of Health and

Family Welfare (MOHFW) Government of India highlighted key steps to be taken by

dentists in addition to the standard universal precautions such as taking

patients’ recent travel history; assessing signs and symptoms of RTI; recording

patients’ body temperature; mouth rinsing with 1% hydrogen peroxide prior to

commencement of any procedure; using a rubber dam and high volume suction

during procedures; and frequently cleaning and disinfecting public contact

areas including door handles, chairs and, washrooms [8]. While the MOHFW has

issued preventive recommendations, most dentists are still hesitant to treat

patients in such a situation and feel afraid. In addition, the new

recommendations may not be known to most dentists. So we conducted a

questionnaire-based study to determine the response of dentists in Himachal

Pradesh.

The

goal of this study was to assess what impact have it made on dental

professionals to tackle the outbreak of the novel Coronavirus disease (COVID-19).

Additionally, the fear of being infected was assessed during the ongoing global

pandemic.

Material and Method

Our

study population consisted of dentists who work in Himachal Pradesh, regardless

of their place of work, either in Private clinics, Colleges & Hospitals, or

Health Centres. This survey was conducted in June 2020. The main instrument to

collect data was an online questionnaire using Google forms and it is available

at: https://forms.gle/sevkGQEKF5UTJxjXA

and validated through intra-class correlation with a strong relation of 0.76.

Upon clicking on the link, the form description assured the confidentiality of

data, informed the dentists of the study objectives and stated that the study

participation was purely voluntary.

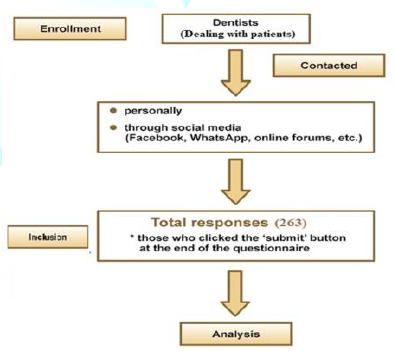

The

dentists’ consent to participate in the study (inclusion criteria) was implied

when they clicked on the ‘Submit’ button after answering the questionnaire, and

they had complete freedom either to decline or answer the questionnaire.

Responses were sought from only those dental professionals who were having

patient dealing and not from other students or any kind.

The

study carried out in June 2020 and both convenience sampling method

(researchers themselves persuaded dentists to take part in the study) and

snowball sampling method (the interested dentists were asked to forward the

questionnaire to their colleagues) was used to ensure full participation. The

questionnaire was distributed personally via various social media platforms

like Facebook and WhatsApp.

The

questionnaire consisted of pre tested; pre-validated self-administered 15 closed-ended

questions. They were concentrated on dentists' fear of being infected with

COVID-19 and were intended to collect information about their practice changes

to combat COVID-19 outbreak in compliance with the recommendations of the Centres

for Disease Control and Prevention (CDCP) and

ADA (American

Dental Association) practice. This also analyzed

anxiety of treating patients in the wake of the spread of this deadly disease.

They were also assessed on their knowledge of various safety precautions that

need to be taken to carry out treatment safely and to guarantee their patients

and they are safe and did the COVID-19 have any effect on their social life as

well. The study was approved by an ethical review board (HDC/ E/03/2020/20),

and statistical analysis on version 25 of Statistical Package for the Social

Science (SPSS) was performed. A Chi-Square and Spearman correlation test was

used to monitor confusers and assess the relationship between dentists in terms

of gender and education.

Results

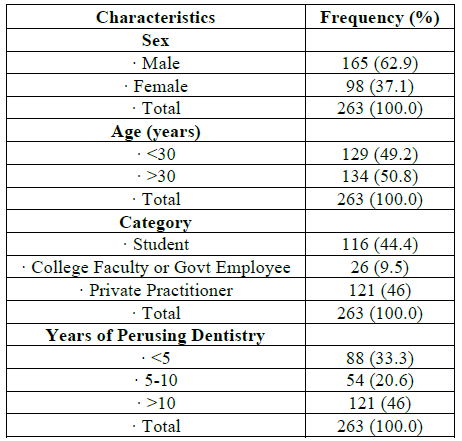

A

total of 263 participants took part, submitting the questionnaire (Figure 2). The majority gender of the

participants was males (62.9%), and females (37.1%). Approximately one half

(46.9%) of the responding dentists were private practitioners, and the

remainder (43.8%) were students (BDS and MDS), whilst other respondents (9.4%)

were College Faculty or Government Employees (Table 1).

Figure 2: Enrollment

and inclusion.

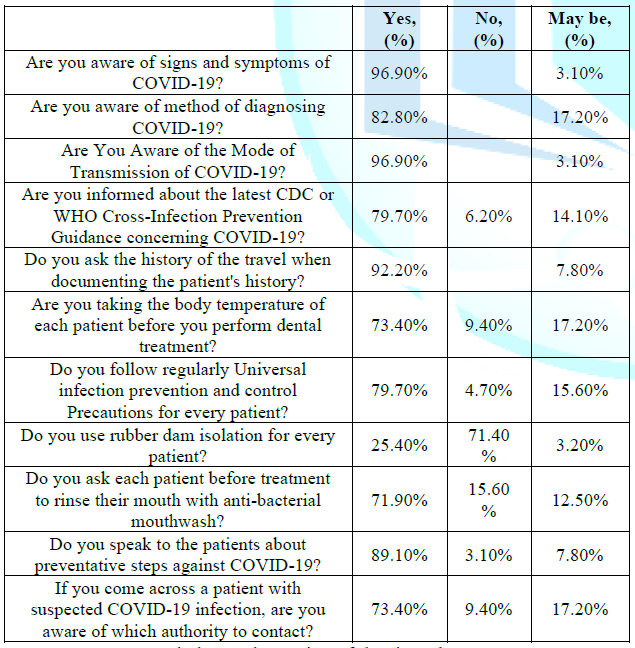

Knowledge and Practice of Dentists about Covid-19

When

asked about awareness towards sign and symptoms, method of diagnosing, mode of

transmission, 96.9%, 82.8%, 96.9% respectively reported that they know about

it. Table 2 reflects the ratio of dentists who registered the multiple answers

about COVID-19

infection. When asked about the latest CDC or WHO

Cross-Infection Prevention Guidance concerning COVID-19, 6.2% simply answered

that they did not know whilst 14.1% were still not sure further having 79.7%

agreeing on having proper knowledge.

Table 1: Demographic

characteristics of respondents of the survey.

Almost

all dentists (92.2%) reported that it is important to take proper travel

history before treating the patient regularly to decrease the possibility of

transmitting infections to patients and to themselves. Whereas only 73.4% take

patients body temperature before the treatment whilst 9.4% do not. While most

(79.7%) advocated standard universal infection prevention procedures, 71.4% did

not use the rubber dam isolation for each patient. That being said, 15.6% did

not ask patients to rinse the mouth with antibacterial mouthwash prior to

dental care and 12.5% still wonders just as 73.4% of the respondents were aware

of the appropriate authority to notify if they stumbled across a patient with a

suspected COVID-19 infection. Last but not the least 89.1% of the responders do

speak about preventive measure to their patients about COVID-19 (Table 2).

Table 2: Knowledge and

practice of dentists about COVID-19 (n=263).

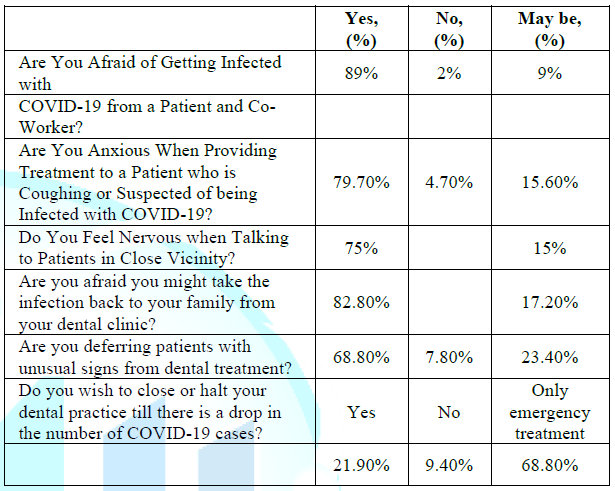

Fear and Anxiety of Dentists about Covid-19

The

nervousness and anxiousness ratios of dental care professionals towards

COVID-19 are listed in Table 3; when

treating a coughing or

a

patient presumed of being infected with COVID-19, 79.7% were anxious and 4.7%

did not find it the same. 89% percent of the respondents were worried about

having COVID-19 infected by either a patient or an employee and 2% otherwise

while other thinking maybe not. And around 75 % of respondents felt nervous

when dealing with patients in close proximity, 82.8% were scared of taking the

disease to their homes by dental office. 68.8 per cent postponed the treatment

of patients with suspicious symptoms. Very few dentists (21.9%) decided to shut

their dental practices until the number of COVID-19

cases began to deteriorate while 68.8%

preferred to provide emergency treatment.

Table 3: Fear and anxiety

of dentists about COVID-19 (n =263).

Discussion

The

current research documented the awareness, anxiety and fear of dentists could

become infected while operating during the ongoing global pandemic. For this

reason, a questionnaire based on closed-ended questions was used to collect

information about the insecurity of dentists and any improvements in protocol

to counter the COVID-19

virus. Questionnaire-based studies are known

to acquire information about participants' interests, behaviors, opinions and

experiences; however careful collecting and analysis of data is needed [9].

Psychological

consequences such as anxiety and fear are common in disease outbreaks,

particularly when there is a dramatic increase in the number of individuals

infected and the mortality rate. Earlier researches of related infectious

diseases such as Severe

Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) have shown multiple

factors contributing to psychological distress in health professionals,

including fear of infection when treating an infected patient, or infecting

their own relative [10,11]. It is basically impossible to classify an

individual's exposure to the virus with the extended incubation period of the

coronavirus (as long as 14 days) [12]. Moreover, there is no antidote or

licensed medication, which further raises fear when it comes to being sick.

Health care staffs who are frequently dealing with sick people are at a greater

risk of contracting infectious diseases, creating a huge psychological cost.

As

it's been documented that the primary route for coronavirus distribution is

through droplets and aerosols, this increases the risk of infection and further

transmission of the disease among dentists and dental healthcare workers. The

present research showed that a significant number of dentists are afraid their

patients or co-workers may get contaminated. The reaction is close to the

perception of the rest of the population, where people are frightened by the

threat of a rapidly emerging epidemic [13]. Many dentists believe any patient

with unusual symptoms should be postponed for treatment. Since COVID-19 has

rapidly affected such a huge number of people in nearly every country, a

physician's fear of getting contaminated is rational. The extreme level of

anxiety was expressed in the fact that a large proportion of dentists decided

to shut down their practices, which could have major economic repercussions for

dentists and dental health workers.

Furthermore,

under these situations, patients who suffer from dental pain and/or follow a

multi-visit treatment program might even have to experience delays with dental

care. The latest COVID-19 outbreak guidelines have recommended that all

non-essential dental care should be delayed, and only patients with discomfort,

swelling, bleeding and trauma are urged to seek treatment [14]. There is a

report published at a dental emergency department in Beijing, China, where

researchers found an effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on dental care activity,

which has decreased in the emergency department compared with pre-COVID-19

coverage [15].

A

further real concern of dentists is that their dental procedures with infected

personnel's can bring infections to their relatives. The Coronavirus can last

from a few hours to a few days on different surfaces [16]. The pressure on the

health sector and the expenses incurred during the treatment after being

infected often imposes stress on one's mind. Health facilities all around are

not nationally funded by the government and one will therefore result in a

substantial financial burden.

A

significant part of this approach was that most respondents were knowledgeable

of the spread and transmission mode of COVID-19. Such information is important

as part of infection control procedures during dental practice. A significant

part of this approach was that most respondents were knowledgeable of the

spread and transmission mode of COVID-19. Such knowledge is vital as part of

prevention measures during dental practice. It was also reassuring that a great

number of dentists were conscious of this present recommendations released by

the Center for Disease Control and the WHO on cross-infection management in

dental practice including questioning for travel history of patients and

documenting body temperature of patients [16]. In this research, 92.2% of

dentists indicated mentioning the travel history when documenting the patient's

history and this was critical in a timely diagnosis that could prevent further

spread of infection.

Understandably,

each of these facts will provide a reasonable understanding in dental practice

of possibly contaminated patients and their preventative management. While most

dentists agreed that such procedures should be followed for each patient,

sadly, unfortunately for every patient a significant number of responders

indicated that they did not use simple cross-infection steps such as the rubber

barrier. Something like a rubber dam is an efficient means of preventing

cross-infection by reducing the spread of aerosols with strong patient

tolerance for dental procedures [17]. Having considered the advantages, there

is no reason not to use rubber dam throughout dental procedures, especially

when using rotary instruments that produce a large amount of aerosols and

droplets.

Rinsing with an antimicrobial mouthwash often greatly decreases the microbial load at the initiation of any dental operation [18]. In the current pandemic, this procedure is recommended but many dentists stated avoiding it. There is currently no evidence sufficient to discuss the impact on COVID 19 of widely used antimicrobial mouth-rinses. This advice may therefore be focused on the fact that gargling has been documented to reduce the distribution of the viral load by eliminating oropharyngeal protease and related viral replication [19].

Most

dentists (89.1%) offered to help raise information about the disease. Any

disease danger alarms to all healthcare workers as they are at greater risk of

infection and it is the essence of their job to treat their patients

courageously. It was noticed that in comparison to graduates, the dentists with

higher qualifications (postgraduates) documented better and substantial

knowledge scores. During the ZIKV and Ebola hemorrhagic fever pandemics, a

number of authors have observed similar outcomes [20, 21]. Harapan et al.

stated that, contrary to our findings, general practitioners had a higher level

of expertise than specialist doctors [22].

Given

the discomfort and distress exhibited by the dental group towards COVID-19, it

is important that psychological coping mechanisms and techniques are exercised

to stay calm and work effectively. The concern dentists have about getting

contaminated with COVID-19 could be significantly reduced if dentists and

dental healthcare staff obey the related guidelines provided by the national

agencies carefully. These include the standardized cross-infection management

systems along with some extra measures in situations where patients with

certain unusual symptoms exist.

A few of the drawbacks of this research are that data have been collected over a brief period of time. Given the rapid impact this epidemic had on the psychology and dental health workers. It can be speculated that dentist perceptions and knowledge could change with the evolving research and potential treatment of COVID-19. Therefore the study's universal applicability is currently minimal. Because this survey was intended to reach the dentist's in Himachal state, and because of regional differences in the way English is spoken and understood, there was an inadvertent chance that the dentists may have faced the questionnaire bias when answering the questions. However, it was established during the execution of the pilot study itself that the questions were kept as objective and clear as possible in order to prevent this kind of bias. Even though current survey included respondents from various Himachal Pradesh cities, each part of the area may have variable COVID-19 knowledge, policies, and guidelines which can directly influence respondents' responses. Likewise, some regions are more impacted than others which could impact administrative, precautionary and health-care steps taken by a particular region which further can also influence the result of a survey.

Conclusion

In contrary, Himachali dentists are aware of the COVID-19 signs, mode of transmission, prevention of infections, and interventions. However, dental practitioners across the state have high standards of expertise and practices even though they are in a state of anxiety and fear while working in their respective fields due to the COVID-19 pandemic effect on humanity. Presently COVID-19's problems across the globe are getting worse every day. Numerous dental practices have either changed their services to emergency care only according to approved guidelines, or closed down practices for an unknown period of time. In the current scenario, it is important that preference be given to dental procedures identified as emergencies by the WHO and that all dental treatments be postponed until the period when the outbreak enters decline. That would be a reasonable move in actions to mitigate further COVID-19 spread.

Acknowledgments

We

are thankful to the institutes for helping in questionnaire circulation;

Himachal dental college, Sundernagar; Govt. Dental College, Shimla; Bhojia

Dental College, Baddi and all the colleagues and Government Dental Officers

that helped circulating the questionnaire around.

References

- Coronavirus

disease (COVID-19) pandemic.

- WHO

Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March

2020.

- Chen

Y, Liu Q and Guo D. Emerging coronaviruses: Genome structure, replication, and

pathogenesis (2020) J Med Virol 92: 418-423.

- World

Health Organization, Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report-97,

World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Tracking the

impact of COVID-19 in India.

- Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention, Interim Infection Prevention and Control

Guidance for Dental Settings during the COVID-19 Response (2019) Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA.

- Fazel

M, Hoagwood K, Stephan S and Ford T. Mental health interventions in schools in

high-income countries (2014) Lancet Psych 1: 377-387. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(14)70312-8

- Guidelines

for Dental Professionals in Covid 19 pandemic situation.

- Lydeard

S. The questionnaire as a research tool (1991) Fam Pract 8: 84-91. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/8.1.84

- Tam

CWC, Pang EPF, Lam LCW and Chiu HFK. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

in Hongkong in 2003: Stress and psychological impact among frontline healthcare

workers (2004) Psychol Med 34: 1197-1204. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291704002247

- McAlonan

GM, Lee AM, Cheung V, Cheung C, Tsang KWT, et al. Immediate and sustained

psychological impact of an emerging infectious disease outbreak on health care

workers (2007) Can J Psychiatry 52: 241-247. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370705200406

- Moorthy

V, Restrepo AMH, Preziosi MP and Swaminathan S. Active quarantine measures are

the primary means to reduce the fatality rate of COVID-19 (2020) Bull World

Health Organ 98: 150. https://doi.org/10.2471/blt.20.251561

- Person

B, Sy F, Holton K, Govert B, Liang A, et al. Fear and stigma: The epidemic

within the sars outbreak (2004) Emerg Infect Dis 10: 358-363. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1002.030750

- Meng

L, Hua F and Bian Z. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Emerging and future

challenges for dental and oral medicine (2020) J Dent Res 99: 481-487. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034520914246

- Guo

H, Zhou Y, Liu X and Tan, J. The impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on the

utilization of emergency dental services (2020) J Dent Sci. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jds.2020.02.002

- Guan

W, Ni Z, Hu Y, Liang W, Ou C, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus

disease 2019 in China (2020) N Engl J Med 382: 1708-1720.

- Madarati

A, Abid S, Tamimi F, Ezzi A, Sammani A, et al.. Dental-Dam for infection

control and patient safety during clinical endodontic treatment: preferences of

dental patients (2018) Int J Environ Res Public Health 15: 2012. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15092012

- Marui

VC, Souto MLS, Rovai ES, Romito GA, Chambrone L, et al. Efficacy of

preprocedural mouthrinses in the reduction of microorganisms in aerosol: A

systematic review (2019) J Am Dent Assoc 150: 1015-1026.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2019.06.024

- Eggers

M, Koburger-Janssen T, Eickmann M and Zorn J. In Vitro bactericidal and

virucidal efficacy of povidone-iodine gargle/mouthwash against respiratory and

oral tract pathogens (2018) Infect Dis Ther 7: 249-259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40121-018-0200-7

- Gupta

N, Randhawa RK, Thakar S, Bansal M, Gupta P, et al. Knowledge regarding Zika

virus infection among dental practitioners of Tricity area (Chandigarh,

Panchkula and Mohali), India (2016) Niger Postgrad Med J 23: 33-37. https://doi.org/10.4103/1117-1936.180179

- Gupta

N, Mehta N, Gupta P, Arora V and Setia P. Knowledge regarding Ebola Hemorrhagic

Fever among private dental practitioners in Tricity, India: A cross-sectional

questionnaire study (2015) Niger Med J 56: 138-142. https://doi.org/10.4103/0300-1652.153405

- Harapan

H, Aletta A, Anwar S, Setiawan AM, Maulana R et al. Healthcare workers’

knowledge towards Zika virus infection in Indonesia: A survey in Aceh (2017)

Asian Pac J Trop Med 10: 189-194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apjtm.2017.01.018

*Corresponding author

Shubh Karmanjit Singh Bawa, Post Graduate, Department of Periodontology and Implantology, Himachal Dental College, Sundernagar, Himachal Pradesh, India, E-mail: skbawa911@gmail.com

Citation

Bawa SK, Sharma P,

Jindal V, Malhotra R, Malhotra D, et al. Assessing the dental practitioner’s

awareness, fear, anxiety and practices to battle the covid-19 pandemic in

Himachal Pradesh, India (2020) Dental Res Manag 4: 34-38.

Keywords

COVID-19, Infection, Dentist, Infection control,

Fear and anxiety, Precautions

PDF

PDF