Introduction

Trauma at the

facial level gives rise to soft tissue and hard tissue injuries, including dental

organs, as well as the bony components that make up the face: mandible,

maxilla, zygomatic bone,

Nasoorbital-Ethmoidal Complex (NOE) and the supraorbital structures. The

jaw is the second facial bone with the highest incidence of fractures in relation

to the other facial bones; second only to the nasal bones, this is due to their

unique shape, mobility, and prominence in the facial skeleton [1].

In a 10-year

retrospective case study carried out in Saudi Arabia to analyze the incidence

and etiology of maxillofacial

fractures, 270 patients were registered with a total of 476 facial

fractures, of which 260 fractures (54.5%) had mandibular involvement, among

which the condyles turned out to be the most affected (11.8%). The main

etiology of maxillofacial fractures are car accidents (63.3%) followed by falls

(15.9%) assaults (6.7%) sports trauma (8.1%) work accidents (8.3%) gunshot

wounds (8.7%) and attacks received by animals (2.2%) [2].

The goal of

treatment in patients with mandibular fractures is to anatomically reduce the

fractured segments or to place each fragment in the appropriate relationship

with respect to the others [1]. To successfully reduce fractures of tooth

bearing bones, the most important thing is to place the teeth in the

previously existing occlusive relationship. To achieve these objectives, closed

reduction by means of Arches of Erich or open reduction and internal fixation

by means of titanium

plates and screws can be used [3-6].

Evaluation of Patients with Facial

Trauma

The primary

assessment encompasses the ABCDE of trauma care and identifies life-threatening

conditions by adhering to this sequence: [7]

A. Maintenance

of the airway and control of the cervical spine.

B. Breathing

and ventilation.

C. Circulation

and hemorrhage control.

D.

Neurological

deficit.

E. Exposure

/environmental control: Completely undress the patient, but prevent hypothermia

Once the patient

is stabilized, a clinical history should be obtained as complete as possible,

detailing precisely all aspects related to the trauma. The five questions to

consider are:

· How

did the accident happen?

· When

did it happen?

· What

are the specific aspects of the injury?

· Was

there loss of consciousness?

· What

symptoms does the patient currently have? [3]

After a

meticulous clinical assessment of the entire maxillofacial

complex and when mandibular

fractures are suspected, radiographs should be taken to provide additional

information for their correct diagnosis. Among the most used projections we

have: [3,8]

·

Orthopantomography: in

this type of X-ray we can detect any type of mandibular fracture.

·

Towne's

projection:

Projection indicated to assess the mandibular condyles.

·

Anteroposterior

and posteroanterior projection of the face: projection

indicated in the event of suspected fractures at the mandibular angles or

condyles.

·

Oblique

lateral projection of the mandible: type of

radiography indicated to assess the mandibular angles.

·

CT of

the facial massif: preferred radiological technique to

study any type of maxillofacial fracture [8].

Classification

Trauma at the

facial level can vary depending on the location, direction and intensity of the

trauma received, which can cause mandibular fractures in its different

locations. One of the classifications is based on the anatomical location in

which the fracture occurred, within which we have: condylar, subsigmoid,

coronoid process, ascending

mandibular ramus, mandibular angle, parasymphyseal, symphysial and

dentoalveolar. Another classification of fractures is based on the state of the

bone fragments and their possible communication with the external environment,

among which we have: greenstick fractures that are the type of incomplete bone

fractures, simple fractures that have no communication with the external

environment, comminuted fractures characteristic of those fractures in which

multiple bone fragments are present, such as those produced with gunshot wounds

and Compound fractures that are characterized by having communication with the

external environment [3].

Depending on the

direction of the fracture line and the muscle action proximal or distal to the

fracture that these exert, mandibular fractures can be favorable or unfavorable

[3]. Favorable fractures are those in which the fracture line is perpendicular

to the muscle action, which causes the fragments to resist their separation,

whereas unfavorable fractures have a line parallel to the muscular action

causing the displacement of the segments.

Treatment

For the treatment of mandibular

fractures, different techniques have been proposed, known as Closed Reduction

(conservative) in which only Intermaxillary Fixation (IMF) and Open Reduction

(surgical) are used, which include opening, exposure and manipulation of the

fractured segments [3]. The first and most important aspect of surgical

correction of mandibular fractures is to reduce the fracture properly. In the

tooth‐bearing bones, it is of outermost importance to place the teeth in a

pre‐injury, occlusal

relationship. Merely aligning the bone fragments at the fracture site

without first establishing a proper occlusal relationship rarely results in

satisfactory postoperative functional occlusion. With interdental fractures,

fracture models are important: impressions poured in Snow‐White plaster and

sectioned at the fracture site allow the assessment of pre‐trauma

occlusion.

Missing teeth,

pre‐existing class II or III, and deep bite deformities may otherwise misguide

the surgeon. To establish a proper occlusal relationship, several techniques

have been described, generally referred to as IMF. The most common technique

includes the use of a prefabricated arch bar that is adapted and circumdentally

wired to the teeth or acid‐etch bonded to each arch; the maxillary arch bar is

wired to the mandibular arch bar, thereby placing the teeth in their proper

relationship. Other wiring techniques, such as Ivy loops or Obwegeser

continuous loop wiring, have also been used for the same purpose [9].

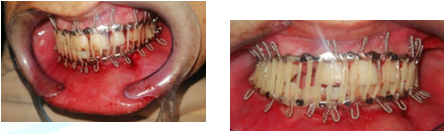

The main

objective of the treatment is to achieve a correct dental occlusion that

existed prior to the fracture, so that only achieving a correct alignment of

the bone fragments without having a satisfactory functional occlusion is not

enough to achieve the desired objectives [3]. The correct dental occlusion

established with the help of wires or elastic traction is known as

intermaxillary fixation, within these several techniques have been established.

The most important and most used are the Erich arches, which consist of prefabricated

arches placed in both dental arches and, with the help of ligating wires or

elastic traction, establish the maxillomandibular

fixation [3,6]. Other techniques used that support the same objective are

Ivy's loop wire ligations, transalveolar screws, Risdon's ligation, Ernst's

ligation, and Essig's ligation. [3,6,10].

The use of elastic traction is important, even more so when the fracture segments are displaced, since they exert a constant force that gradually causes a satisfactory reduction of the fracture, and in cases of condylar fractures since immobilization by long-term can cause ankylosis of the Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) (Figure 1 and 2) [5].

Figure1:Prefabricated archwires (Erich's archwires) and elastic traction to restore ideal occlusion

Figure2:Ivy handle placed between premolars of the quadrants for IMF.

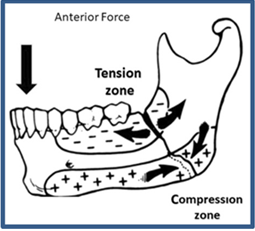

Titanium plates

and screws are used in open reduction plus internal fixation. Pioneers such as

Michelet and Champy had the greatest impact on the evolution of osteosynthesis

in maxillofacial trauma. Their concept states that when a physiological load is

applied to the mandibular teeth, a negative tension is created on the upper

edge and a positive pressure will appear on the lower edge (Figure 3) [11].

Figure 3: Biomechanics of mandibular angle fractures.

Among the

advantages of internal fixation with respect to closed reduction is the greater

comfort for the patient since the IMF is eliminated or reduced depending on the

location and type of fracture, better feeding and postoperative hygiene, better

results in the presence of unfavorable fractures, less inconvenient in patients

with seizures [3]. In the treatment with closed reduction or open reduction

plus osteosynthesis of mandibular fractures, multiple complications can occur,

and this due to the little experience of the operator or poor planning of the

case to be treated. Among the most frequent complications are facial asymmetries,

dental problems, nerve injuries, infections, pseudoarthrosis,

osteonecrosis, limitation of mouth opening, malocclusions, and wound dehiscence

(Figure 4) [12-15].

Case 1

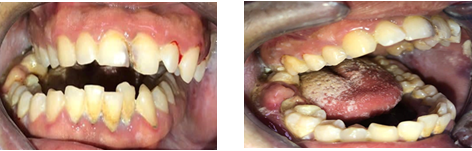

A systemically

stable 20-year-old male patient who attends the CBMF-HEU service, who reports

having been physically assaulted, receiving a blunt blow to the face with a

baseball bat at the time he was about to board his motorcycle, denies loss of

awareness. On physical examination, he presented facial asymmetry and swelling

in the right parotid region, painful on palpation and when opening the mouth (Figure 5).

In the intraoral

clinical examination, a mandibular bone fracture was observed, compromising

dental organs 3.1 and 3.2, with mobility of the segments, poor dental

occlusion, and a wearer of a removable partial denture of a “Wipla” type unit

that replaces the organ dental 1,2 absent. A panoramic radiograph is indicated

in which a solution of continuity is seen in the right mandibular angle and the

left

parasymphysis (Figure 6 and 7).

Diagnosis:

Compound fractures of the right mandibular angle and left parasymphyseal, which

was reduced by means of the conservative method with the Erich arch technique.

It began by placing the prefabricated bar in the upper jaw secured with

ligating wires, and the reduction of the lower jaw fractures continued in the

same way. Lastly, the IMF was performed with the help of elastic traction by

means of orthodontic bands of 3.2 mm and 6½ ozs. A control appointment is

indicated every two weeks for the change of leagues until reaching 8 weeks with

the Maxillomandibular Fixation (MMF).

Figure5:Frontal view showing facial asymmetry and lacerations in the left parasymphyseal region

Figure6:Intraoral photographs showing malocclusion and dental displacement of 3.1 and 3.2..

In the evolutions

after the therapy implemented in the patient, a satisfactory anatomic reduction

of the fractures was achieved, an optimal dental occlusion that is confirmed

with the postoperative

panoramic radiograph and clinical improvement of the initial symptoms, the

discharge is decided by the oral and maxillofacial surgery unit (Figure 8 and 9).

Case 2

A 21-year-old

male patient without systemic compromise is received, who attends the oral and

maxillofacial surgery service of the Hospital Escuela Universitario referred

from the plastic surgery service of the same healthcare center, with a history

of cranioencephalic trauma secondary to a motor vehicle collision-type road

accident, self, not wearing a helmet, with trauma to the frontal and mandibular

region, with subsequent loss of consciousness and expression of an encephalic

mass. On the extraoral

clinical examination, he presented multiple wounds in the upper third and

middle facial region, surgical suture in the frontal region, ocular dystopia

without visual disturbances, and labial incompetence (Figure 10).

Figure10:Frontal view showing multiple facial injuries, ocular dystopia, and labial incompetence.

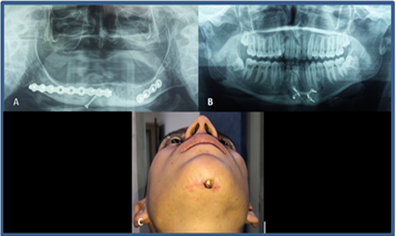

The intraoral

clinical examination revealed a displacement of the mandible to the right side

with loss of continuity of the occlusal line in the area of dental organs 4.7

and 4.6, occlusal incompetence and abundant deposit of bacterial plaque and

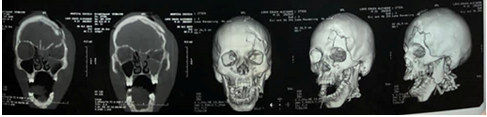

lingual coating. In the Computerized Axial Tomography of the facial massif with

three-dimensional reconstruction, a solution of continuity is observed in the

frontal bone of the left side and left mandibular angle and right mandibular

body. In the medical-surgical history, the neurosurgery department intervened

surgically in which he underwent frontal squirlectomy and drainage of the

epidural hematoma (Figure 11 and 12).

Diagnosis:

frontal bone fracture and compound fracture of the left mandibular angle and

the right mandibular body. A closed reduction of the mandibular fractures was

carried out using the Erich arch technique. Prefabricated bars were placed in

both jaws, secured with ligating wires; the IMF was performed with the help of

elastic traction using 3.2 mm and 6½ ozs orthodontic bands. A control

appointment is indicated every two weeks for the change of leagues until

reaching 8 weeks with the MMF (Figure 13

and 14).

Figure11:Intraoral photographs showing mandibular displacement with occlusal incompetence.

Figure12:CT scan of facial mass showing fracture of the frontal and bilateral mandible bone.

Figure13:Erich arches placed in the upper and lower jaw.

Figure14:IMF with optimal dental occlusion

In the evolutions

after the therapy implemented in the patient, a satisfactory anatomical

reduction of the fractures was achieved, an optimal dental occlusion that is

confirmed with the postoperative panoramic radiograph and clinical improvement

of the initial symptoms, the discharge is decided by the oral and maxillofacial

surgery unit (Figure 15).

Case 3

A 19-year-old

male patient who attends the oral and maxillofacial surgery service of the

University School Hospital referred from the plastic surgery service of the

same healthcare center, with a 10-day history of motorcycle rollover-type

facial trauma, non-carrier helmet without loss of consciousness. On the

extraoral physical examination, he presented wounds in the frontal, nasal and

nasolabial areas without facial asymmetry. In the intraoral examination, he

presented a total superior unimaxillary prosthesis with absence of dental organ

[2,3]. A panoramic X-ray is indicated in which a solution of continuity is seen

in the left parasymphyseal region (Figure

16 and 17).

Figure16:Frontal view showing multiple facial wounds.

Figure17:Panoramic radiograph showing the left mandibular parasymphyseal fracture.

Diagnosis:

Compound fracture of left mandibular parasymphysis. Open reduction of the

mandibular fracture was carried out for the placement of titanium plates and

screws due to the total edentulism

of the maxilla. Dieresis and tissue dissection were performed through an

intraoral approach used with an electrosurgical device until the fracture lines

were exposed, then a 6-hole titanium plate with 2.0 profile and 6 screws was

placed, achieving a reduction ideal anatomical pattern of the fracture

confirmed with the control panoramic radiograph (Figure 18-20).

Figure18:Exposed fracture traces.

Discussion

In facial trauma,

the mandibular fracture is one of the most common. According to what has been

seen, the most common cause is the motorcycle accident, followed by violent

accidents (stab wounds, or gunshot wounds), among others. Among the patients

attended, there is a higher percentage in male patients. The treatment

of mandibular fractures varies, with the objective of preserving the

occlusion and maxillomandibualar function. It is debated whether between

conservative management with mandibular fixation; According to Daniel Briones

et all, in his comparative study between surgical treatment vs. non-surgical

treatment, less complex fractures resolve in accordance with non-surgical

treatment, while more complex mandibular fractures resolve better with surgical

treatment.

Conclusions

Open reduction

plus internal fixation or closed reduction as conservative treatment are the

alternatives in patients with mandibular fractures accompanied or not by other facial

fractures, the choice of treatment will depend on various factors such as:

the condition of the fractured bone segments, anatomical location of the

fracture, surgeon's management preferences, and even the socioeconomic status

of the patient. This study provides useful information for the diagnosis and steps

to follow for the management of these patients. The majority of patients

treated were men, where most of the cases were motorcycle accidents [8,9,12,16].

References

- Park KP, Lim SU, Kim JH, Chun WB, Shin

DW, et al. Fracture patterns in the maxillofacial region: a four-year

retrospective study (2015) J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofa Sur 41: 306-316.https://doi.org/10.5125/jkaoms.2015.41.6.306

- Al-Bokhamseen M,

Salma R and Al-Bodbaij M. Patterns

of maxillofacial fractures in Hofuf, Saudi Arabia: A 10-year retrospective case

series (2019)

Saudi Dent J 31: 129-136.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sdentj.2018.10.001

- Hupp J, Ellis E and Tucker M. Contemporary

oral and maxillofacial surgery (2014) Elsevier,

Spain, pp-491-518.

- Falci SG,

Douglas-de-Oliveira DW, Stella PE and Santos C R. Is the Erich arch bar the best intermaxillary

fixation method in maxillofacial fractures? A systematic review (2015) Med

oral patologia oral y cirugia bucal 20: e494-e499. https://doi.org/10.4317/medoral.20448

- Nunes Ota TM,

Rodrigues Couto A, de Menezes S, Viana Pinheiro JJ and Ribeiro Ribeiro AL. An alternative approach for treating

severe injured temporomandibular joints by gunshot wounds (2019) Ann Maxillofa Sur 9: 393-396. https://doi.org/10.4103/ams.ams_35_19

- Sandhu YK, Padda S, Kaur T, Dhawan A,

Kapila S, et al. Comparison of efficacy of transalveolar screws and

conventional dental wiring using erich arch bar for maxillomandibular fixation

in mandibular fractures (2018) J Maxillofa Oral Sur 17: 211-217.https://doi.org/10.1007/s12663-017-1046-3

- Stewart R, Rotondo M and Henry S.

Advanced trauma life support (2018) 10th Ed Chicago: American

College of Surgeons, United States, pp-2-21.

- Shah S, Uppal SK, Mittal RK, Garg R,

Saggar K, et al. Diagnostic tools in maxillofacial fractures: Is there really a

need of three-dimensional computed tomography? (2016) Indian J Plas Sur 49:

225-233. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-0358.191320

- José M López‐Arcas. Intermaxillary Fixation

Techniques (2018) EACMFS Education and Training, Belgium.

- Qureshi AA, Reddy UK, Warad NM, Badal S,

Jamadar AA, et al. Intermaxillary fixation screws versus Erich arch bars in

mandibular fractures: A comparative study and review of literature (2016) Ann Maxillofa

Sur 6: 25-30. https://doi.org/10.4103/2231-0746.186129

- Bohluli B, Mohammadi E, Oskui IZ and

Moaramnejad N. Treatment of mandibular angle fracture: Revision of the basic

principles (2019) Chinese J Traumatol 22: 117-119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjtee.2019.01.005

- Hsieh

TY, Funamura JL, Dedhia R, Durbin-Johnson B, Dunbar C, et al. Risk factors

associated with complications after treatment of mandible fractures (2019) JAMA

Fac Plas Sur 21: 213-220.https://doi.org/10.1001/jamafacial.2018.1836

- Zhou

HH, Lv K, Yang RT, Li Z, Yang XW, et al. Clinical, retrospective case-control

study on the mechanics of obstacle in mouth opening and malocclusion in

patients with maxillofacial fractures (2018) Scien Rep 8: 7724. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25519-0

- Ravikumar

C and Bhoj M. Evaluation of postoperative complications of open reduction and

internal fixation in the management of mandibular fractures: A retrospective

study (2019) Indian J Dent Res 30: 94-96. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijdr.ijdr_116_17

- Kim

SY, Choi YH and Kim YK. Postoperative malocclusion after maxillofacial fracture

management: a retrospective case study (2018) Maxillofac Plas Recons Surg 40:

27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40902-018-0167-z

- Daniel

Briones. Comporative Study between Surgical Treatment vs Non-Surgical Treatment

of Mandibular Fractures (2004) Dent Mag Chile 95: 11-16.

Corresponding author

Hugo Romero, Department of Oral

and Maxillofacial Surgery, National Autonomous University of Honduras, Honduras,

E-mail: cmfalvarenga@gmail.com

Citation

Romero H, Guifarro J, Diaz F, Umanzor V, Pineda

M, et al. Management of mandibular fractures: report of three cases (2021)

Dental Res Manag 5: 17-22.

Keywords

Fracture jaw, Closed reduction, Open reduction,

Internal fixation

PDF

PDF