Research Article :

Maria Marta Amancio Amorim,

Giselle Antunes da Silva, Stephanie Caroline Medeiros Lopes,

Tamara Augusta de Magalhães Gonçalves Santos and Alessandra Hugo de

Souza Methods:

This is a longitudinal observational study performed with men and women with

obesity in the second half of 2017. Sociodemographic, clinical, anthropometric

and nutritional data were collected from 216 clients. The greatest demand for

the service was of women, in the age group of 20 to 59 years, in the masculine

sex there was the greater amount of stylist. Regarding the level of schooling

and physical activity the predominance was female, but the number of smokers

was equal in both sexes. Results

and Discussion: The reported diseases were 16.47% with

arterial hypertension in the female sex. However, a 24.07% share of total

treatment withdrawal occurred. The female sex obtained the highest number of

consultations performed on average (2.62), but there was a satisfactory weight

loss, established according to the number of consultations performed. The

greatest weight loss was in the male sex, equivalent to (12kg). Conclusion: The prescribed diet needs to be well planned

according to the individuality of each patient, performed and evaluated

throughout the process; it requires continuity, effort and permanence in the

treatment. Obesity can be conceptualized in a simplified way,

as a condition of abnormal or excessive accumulation of fat in the body,

leading to a compromised health. The degree of excess fat, its distribution and

its association with health consequences vary considerably among obese

individuals. Obesity

has emerged as an epidemic in developed countries during the last decades of

the twentieth century. However, it currently reaches all socioeconomic levels

and has increased its incidence, also in developing countries. The prevalence

of obesity in the world and Brazilian population has become a major public

health problem and may promote diseases associated with overweight and the with

consequences of diabetes mellitus type2, hypercholesterolemia, breathing

difficulties, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease and certain types of cancer,

sleep apnea, psychosocial disorders and osteoarthritis [1-3]. According to the Survey on Risk Factors and

Protection for Chronic Diseases by Telephone Survey, one in five people in the

country are overweight. The prevalence of the disease went from 11.8% in 2006

to 18.9% in 2016. According to the World Health Organization, it is projected

that by 2025 about 700 million adults are obese and the number of overweight

and obesity in the world can reach 75 million if there is no intervention. The

etiology of obesity is not easily identified and can be classified into two

contexts: the first by genetic determination or endocrine and metabolic

factors. The second refers to external factors, whether of dietary, behavioral

or environmental origin. External factors are believed to be more relevant in

the incidence of obesity than genetic factors. Clinical treatment of obesity

can be both drug

and non-drug. The patient should understand that weight loss is much more than

a cosmetic measure and aims at reducing morbidity and mortality associated with

obesity. Losses of 5 to 10% of initial body weight are

associated with significant reductions in blood pressure, blood

glucose and serum lipid values [4-7]. Drug treatment serves as auxiliary

treatment and, in conjunction with changing habits, may decrease weight gain

[1]. With all the advances, a drug that could fight obesity has not yet been

developed, so changing eating habits and physical activity, non-drug treatment

is the most efficient ways to reverse and prevent this condition. In the

context of non-drug treatment, the Integrated Health Care Clinic of the UNA

University Center, in Brazil empowers nutrition course teachers to provide

nutritional care to the external public with difficulties in accessing primary

care in different pathologies, such as obesity. Thus, the objective of this

study is to characterize the nutritional profile of obese clients treated at

the Integrated Health Care Clinic of the UNA University Center, Belo Horizonte,

Minas Gerais [8,9]. This is an observational, longitudinal study

conducted with obese clients seen at the Integrated Health Care Clinic, located

at the UNA University Center, Belo Horizonte, Brazil. The study was approved by

the Ethics Committee of the UNA University Center under opinion number CAAE

67531517.2.0000.5098. Sociodemographic, clinical, anthropometric and

nutritional data of obese clients, attended in the second half of 2017, were

collected from medical records. The sociodemographic data collected were: gender,

schooling age, clinical: reason for consultation, diseases, smoking,

alcoholism, physical activity practice and anthropometric: current weight,

height, WaistCircumference (WC), Bicipital Fold (BF), Tricipital Fold (TF), Subscapular

Fold (SCEF) and Suprailiac Fold (SIF). To measure body weight, a Welmy® digital scale was

used with a stadiometer coupled with a maximum capacity of 150 kg, with

individuals standing barefoot with their backs to the scales. The height of the

clients was also measured, with the arms extended close to the body, head

elevated. Using weight and height, the Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated by

the formula weight/height² (kg/m²). They used the cutoff points to classify the BMI of

adolescents, adult and elderly. Waist circumference was measured with an

inextensible tape measure, with the abdomen relaxed, arms relaxed at the side

of the body, and the tape placed horizontally at the midpoint between the

bottom edge of the last rib and the iliac crest, according to the reference

manual anthropometric analysis. To classify WC, the stipulated value of ≥ 102

cm for men and ≥ 88 cm for women was used as the American best indicator of

obesity and cardiovasculardiseases [10-16]. The technique for making all adipose folds should be

on the right side of the body, carefully identifying, measuring and marking the

location of the adipose folds. It is necessary to define the major axis of the

fold and it should be held firmly between the thumb and forefinger, left hand.

The body fat percentage was calculated by summing the values in mm of the BF,

TF, SCEF and SIF folds, and then finding the corresponding value, according to

age and gender. Nutritional data of energy values were collected

from the 24-hour dietary recall method (R24h), which quantifies the foods and

drinks consumed on the previous day. Like the R24h the prescribed diet was

calculated by the Diet box Professional version 2017 software. Weight loss and number

of consultations was collected from the clients first return to the clinic to

seek diet and so on. All data were distributed by sex and age group:

adolescents from 13 to 19 years old, adults from 20 to 59 years old and elderly

from 60 to 86 years old [17-20]. In the second semester of 2017, 922 clients were

assisted, of which 216 met the inclusion criteria of the survey, where they

were classified based on the degree of obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m²).As observed in

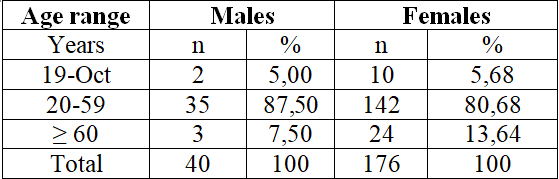

Table 1, among the 216 clients who were evaluated, females prevail over males,

with age ranging from 20 to 59 years. Table 1: Gender and age range of clients

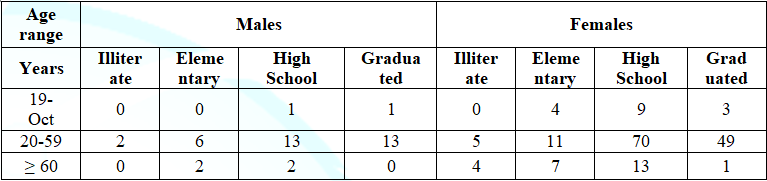

seen at the UNA Integrated Health Care Clinic, period 2/2017. Table 2 and Table 3 show the educational level of

the patients, ranging from illiterate to graduates with complete higher

education and the use of tobacco, alcohol and physical activity. Regarding the clinical data collected, the reasons

for seeking care in the clinic reported by the patients were: dietary reeducation,

weight loss, obesity, medical indication and diseases in which they intended to

control or even suppress them. The most informed diseases were hypertension,

type 1 and ll diabetes,

obesity,

and hyperthyroidism.

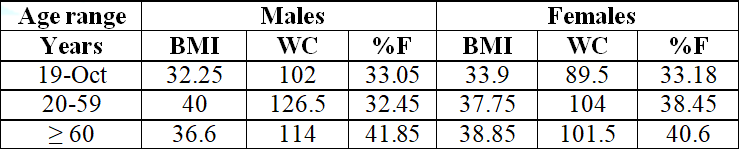

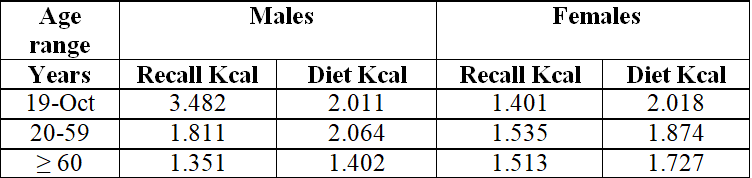

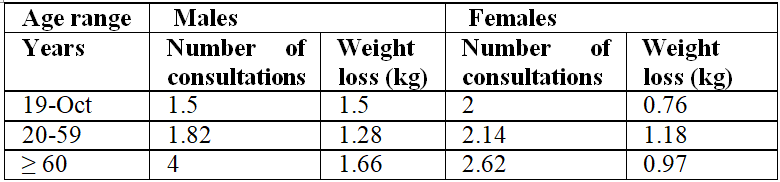

Table 4 and Table 5 show the average data related to anthropometric assessment

and dietary intake of clients evaluated at the Clinic. Table 6 shows the

average number of consultations and weight loss. Table 5: Food recall and prescribed diet,

distributed by sex and age group, of clients treated at the UNA Integrated

Health Care Clinic, period 2/2017. Regardless of age group, it was found that females

had more demand for clinical nutritional care, highlighting the age group of 20

to 59 years (Table 1). According to Oliveira, in Brazil, women are

characterized by greater demand for nutritional care, seeking control and

treatment of possible diseases. Usually men have a reluctance to seek care.

Regarding the level of education (Table 2) the age group of 20 to 59 years, in

both sexes, high school had the highest demand for nutritional care. According to the Brazilians Oliveira patients

education is fundamental to the success of the nutritional education work,

since the concepts of healthy eating and proper food substitutions are often

complex. Thus, care must be taken with the technical terms and concepts of nutrition science when

targeting patients of different educational levels [21]. Since basic education

there is a need for a nutritional approach, so that the client can grasp the

importance of a healthy life, which will extend for a lifetime. Nutrition

knowledge can also influence eating habits, suggesting that nutrition education

is incorporated into the Brazilian school curriculum, actively involving

teachers, the school community and family, in order to provide nutrition

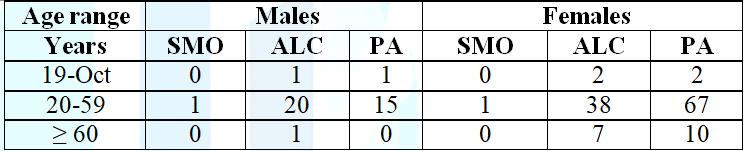

information and aspects related to food. Regarding smoking (Table 3), similar results were

obtained for both sexes, aged between 20 and 59 years old. According to the

Ministry of Health, the age group with the highest prevalence of smokers in

Brazil is from 20 to 49 years old, with a higher proportion of men. However, in

recent years, the percentage of women has increased, as in the present study,

where cigarette consumption by men and women was equal. According to Klein,

smoking cessation can lead to a 75% increase in body weight in both sexes. Most

studies related to smoking cessation and weight gain indicate that there is an

increase in sweet food intake after cessation as a compensatory mechanism

[22-25]. Regarding the consumption of alcoholic beverages, a

greater number of alcoholics in the age group of 20 to 59 years old were

identified in both sexes, from occasional consumption once a month to

consumption 1 to 3 times a week. However, males stood out when compared to

females. Considering that alcohol has energy value, it has the ability to suppress

an individuals daily energy needs or overweight, depending on the amount,

frequency and mode of consumption. Even with increased basal energy expenditure

in alcoholics, this is often not enough to compensate for the large amount of

energy intake. Thus, many alcohol-dependent individuals have overweight, obesity

and even waist circumference above expected standards [26-29]. Among the practitioners of physical activity (Table

3), we highlight the age group of 20 to 59 years, in both sexes. Female clients

practice a little more physical activity compared to male individuals. More

than half of male clients do not practice any physical activity and the age

group ≥ 60 years old have the worst result. In females, all age groups practice

physical activity, but half of the clients did not practice any physical

activity. The reported physical activities were characterized between walking,

bodybuilding, Pilates, cross fit, volleyball, dance, running, aerobic among

others. The World Health Organization recommends that adults perform physical

activities in a variety of ways, such as through recreation, leisure,

commuting, household chores, sports, or structured exercise. Although these physical activities recommended for

health, they should be designed in a special way for those who aim to reduce or

control body weight. There is a consensus among researchers that physical activity is

the best variable of energy balance components to predict success in

maintaining body weight loss. People do not have enough time to perform

constant physical activities, directly contributing to the concentration of

excess body fat. Therefore, exercise should be recommended for obese

individuals [30-33]. Regarding the reason for seeking nutritional care

performed at the Clinic, it was found that dietary reeducation, obesity and

weight loss were the main reasons for both sexes, in the age group of 20 to 59

years old. The largest demand among women occurred in all age groups. Overall,

women use health services more than men, as women are more interested in their

health, seeking more health services for routine screening and preventive care,

while men are seeking more curative care [34,35]. Regarding illnesses, around

half of male and female clients reported having no disease. The age group of 20 to 59 years in females accounted

for the highest percentage of reported diseases: 16.47% hypertension, 15.34%

obesity, 2.11% with type 2 diabetes mellitus. The same age group also stood out

in the male gender, identifying 25% with hypertension, 5% diabetes mellitus type 2

and 5% with obesity. The increased BMI, WC and %F values described in Table 4

demonstrate the importance of intensifying multi-professional follow-up. The

highest BMI index was obtained in males (40 kg/m²), in the age group from 20 to

59 years old and in females (38.85 kg/m²) in those older than 60 years. Lower values were found in another Brazilian study

in a state bank: male group (36%) and women (17%) [36]. WC, the best indicator

of obesity and cardiovascular disease, was above the standards indicated in

both sexes, with a value of ≥ 102 cm for men and ≥ 88 cm for women, 19. The

highest WC recorded was in the age group of 20 years. 59 years old, male, with

an average of 126.50 cm. The classification of fat percentage in women is

estimated at <21% malnutrition, 21 to 32% eutrophic, 33 to 38.9% pre-obesity

and >39% obesity. Males <8 malnutrition, 08 to

19.9% eutrophic, 20 to 24.9% pre-obesity, >25% obesity [37]. According to %F measured in the patients treated,

there was a slight variation in relation to the data. Men and women, with the

highest %F occurring in the age group of ≥ 60 years old in males with a mean of

41.85%. However, another study shows that the increase in body fat is higher in

females, between 60 and 78 years old [38]. In studies by Matsudo, in Brazil,

showed that over the years there is an increase in body fat and a reduction in

lean mass in men and women. Data from the R24h reported by clients and the

prescribed diet (Table 5) showed that the diet presented average energy

consumption data higher than the dietary recall in the age group of 20 to 59

and ≥ 60 years old in both sexes, due to fact that customers have difficulty or

are afraid to report their food intake [39]. The exception occurred only in the age group of 10

to 29 years in males, where the prescribed diet was lower than the 24-hour

recall described by clients. In addition to the difficulty in correctly

reporting the quantification of ingested foods, other factors are related to

nutritional status and pathologies, in Brazilian study, people with low weight

can stipulate the intake of food consumed, on the other hand, obese individuals tend

to decrease this amount because the presence of diseases can lead to a memory

bias report. Recent studies show that the Brazilian diet has been

increased with low nutrient and high calorie foods, called the risk diet. A

high carbohydrate and lipid diet will certainly lead to obesity, as will a lack

of physical activity to expend the excess energy accumulated. But unlike the

genetic factor, the environmental factor can be reversed [40-42]. The prescribed diet is designed according to the

specificity of each patient, and should respect the possibility of each one to

follow the suggested diet plan for weight loss. Dietary planning is based on

the establishment of habits and practices related to food choice, eating

behaviors, adequacy of energy expenditure and reduction of energy intake that

will have to be incorporated in the long term, according the study conducted in

Brazil [43]. Table 6 presents the average number of consultations and weight

loss. The

average number of consultations ranged from 1.5 to 04, where men stood out with

a higher average of consultations, in the age group above 60 years, followed by

the female group of the same age group. Weight loss ranged from 1 to 12 kg among males, and

the highest average was found in the age group ≥ 60 years old. The female group

had a higher average weight loss, aged 20 to 59 years, followed by the group

above 60 years. The World Health Organization recommends for moderately obese

individuals (BMI<35.0 kg/m²) a weight reduction of 5% to 15%, which can be

achieved through a nutritionally

adequate

diet that is easier to manage and maintain [44]. In addition, losses in these

proportions are related to a significant reduction in associated comorbidities

[43]. According to Willett the recommendation for dietary

reeducation, conduct and the practice of eating healthy foods are stimulated

aiming at progressive weight loss over time. Similarly, the percentage return

of clients to the clinic shows a progress directly linked to weight loss, as

seen in Table 6. The main limitation of this study is that the data collection

was made from the Clinic Excel spreadsheet, which calculates the average

customer data and has no median values and percentage distribution. It is known

that the average values do not reflect the nutritional status of the clients.

Like anthropometric data, the clinics software has only average weight loss data [45]. According to the data presented, the greatest demand

for nutritional care was for obese women aged 20 to 59 years old. However, the

study showed that the male group stood out with a higher prevalence in BMI, WC

and %F. The educational level was dominated by individuals with high school in

the age group of 20 to 59 years old in both sexes. Smoking had the same number

of clients for both male and female clients. As for alcohol, it identified the

male customers with the highest consumption, aged between 20 and 59 years old. However the practice of physical activity obtained

the highest prevalence when compared with the opposite sex in the age group of

20 to 59 years old. In both sexes there was a proportion of treatment dropout.

The largest number of appointments at the clinic was female, highlighting the

age group from 20 to 59 years old. However, the greatest weight loss was recorded

in males aged ≥ 60 years old, presenting a satisfactory weight loss among

patients who remained assiduous at the appointments. Given this, it was

emphasized the need for permanent and persevering nutritional care, evidencing

weight loss. The prescribed diet, therefore, must be well planned

according to the individuality of each patient, executed and evaluated

throughout the process, requires continuity, effort and permanence in the

treatment. According to Amorim et al., 2018 the clients presence in the office

proved to be fundamental for improving the anthropometric profile of people

with obesity,

however adherence to treatment is influenced by numerous factors that still

need to be studied, as data are scarce in literature [46]. We

thank Maria Cristina Santiago, advisor professor at the Integrated Health Care

Clinic, Una University Center, Brazil. 1. World

Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic.

Geneva 1998. 2. Bernardi

F, Cichelero C and Vitolo MR. Dietary restriction behavior and obesity (2005)

Rev Nutr 18: 85-93. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1415-52732005000100008

3. Monteiro

CA and Conde WL. The secular tendency of obesity according to social strata:

northeastern and southeastern Brazil 1975-1989-1997 (1999) Arq Bras Endocrinol

Metabol 43: 186-94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0004-27301999000300004

4.

Brazil.

Brazilian Association for the Study of Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome (2016)

Brazilian Obesity Directive, Sao Paulo 4: 16-20. 5.

Aguiar

SR and Manini R. The Physiology of Obesity: Genetic, Environmental Bases and

Their Reaction to Diabetes (2013) With Science 145: 6-27. 6.

Bouchard

C. Physical activity and obesity. Sao Paulo: Manole; 2000. 7.

Wadden

TA and Foster GD. Behavior treatment of obesity (2000) Med Clin North Am 8:

441-461. http://10.1016/s0025-7125(05)70230-3

8.

Bays

He. Current and investigational antiobesity agents and obesity therapeutic

treatment targets (2004) Obes Res 12: 197-211. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2004.151

9. Amorim

MMA, Santiago MC and Azevedo DQ. Building Interdisciplinary Training at the

Integrated Health Clinic at UNA University Center/Belo Horizonte/Brazil

[Construction of Interdisciplinary Training at UNA Integrated Health

Clinic/Belo Horizonte/Brazil] In: Rangel, MLS, Ramos, N) Communication and

health: contemporary perspectives. Salvador 2017-2018. 10.

Jelliffe

DB. The assessment of the nutritional status of the community (1966) Monogr Ser

World Health Organ 53: 3-271. 11.

World

Health Organization. Physical status: The use and interpretation of

anthropometry. Geneva 1995 12.

Cole

TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flxegal KM and Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition

for child overweight and obesity worldwide (2000) international survey 320:

1240-1242. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240

13.

World

Health Organization. The physical state: use and interpretation of

anthropometry (1995) Genebra 452-854. 14.

Lipschitz

DA. Screening for nutritional status in the elderly (1994) Primary Care 21:

55-67. 15.

Callaway

CW, Chumlea WMC, Bouchard C, Himes JH, Lohman TG, et al. Circunferences in

Anthropometric standardization reference manual (1998) 39-54. 16.

Nhlbi.

Obesity Education Initiative Expert Panel. Clinical Guidelines on

Identification. Evaluation and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults.

The Evidence Report; 1998. Available in:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2003/. Acess in 2 Dec 2018 17.

Moreira

MH. Adipose Fold Evaluation. University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro: Vila

Real 1995. 18. Durnin

JVA and Worsley J. Body fat assessed from total body density and its estimation

from skinfold thickness (1974) British J Nutr 32: 77-97. https://doi.org/10.1079/bjn19740060

19.

Gibson

RS. Principles of nutritional assessment. Oxford: Oxford University Press (1990)

Food consumption of individuals. 37-54 20.

Buzzard

M. 24-hours dietary recall and food record methods. In: Willett WC (1998) Nutr

Epidemiology 50-73. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195122978.003.04

21.

Oliveira

AFL de S and Fatel EC de S. Profile of Patients Seeking Nutritional Care (2008)

Guarapuava 2: 15-21. 22. RM

Triches and Giugliani ER. Obesity, eating practices and nutrition knowledge in

schoolchildren (2005) Rev Saude Publica 39: 541-547. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0034-89102005000400004

23.

Brazil.

Ministry of Health. National Cancer Institute. Smoking in Brazil and worldwide. 24.

Klein

LC, Corwin EJ and Ceballos RM. Leptin, hunger, and body weight: Influence of

gender, tobacco smoking, and smoking abstinence (2004) Addict Behav 29:

921-927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.023

25. Rosemberg

J, Rosemberg AMA and Moraes MA. Nicotine: universal drug [Nicotine: Universal

Drug]. Sao Paulo 27.

Suter

PM. Is alcohol consumption a risk factor for weight gain and obesity? (2005)

Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 42: 197-227. 28.

Vadstrup

ES, Petersen L, Sorensen TIA, Grombaek M. Waist circumference in relation to

history of amount and type of alcohol: results from the Copenhagen City Heart

Study. Int J Obesity 2003; (27): 238-246. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.802203

29.

Kachani

AT, Cardoso A, Furtado Y, Barbosa ALR, Brasiliano S, et al. Waist circumference

measurement in alcohol and drug-dependent women. In: XXVIII Congress of the

Society of Cardiology of the State of São Paulo (SOCESP) 2007. 30.

https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44399/9789241599979_eng

31.

Dishman

RK, Washburn RA and Heath GW. Physical activity and obesity. In: Physical

activity epidemiology (2004) Champaign: Hum Kineti 165-188. 32.

Keller

S and Schulz PJ. Distorted food pyramid in kids programmes: a content analysis

of television advertising watched in Switzerland (2010) Europ J Pub Healt 3:

300-305. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckq065

33. Wallace

JP, Ray S, Moore GE, Painter PL and Roberts. ACSMS exercise management for

persons with chronic diseases and disabilities (2009) Champ Hum Kinetic. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2012.677794

34.

Verbrugge

LM. The Twain meet: empirial explanations of sex differences in health and

mortality (1989) J Hel Soc Behavi 30: 282-304. 35.

Cherry

DK and Woodwell DA. National ambulatory medical care survey: 2000 summary.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advanced Data No. 328, June 5, DHHS

Publication No. (PHS) 2002; 1250, 02-0379 (5/02). 36. Ell

E, Camacho LAB and Chor D. Anthropometric Profile of State Bank Employees in

the State of Rio de Janeiro (1999) Cad Public Health 15: 113-121. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-311x1999000100012

37.

Gallagher

D, Heymsfield SB, Heo M, Jebb SA, Murgatroyd PR, et al. Healthy percentage body

fat ranges: an approach for developing guidelines based on body mass index

(2000) Am J Clin Nutr 72: 694-701. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/72.3.694

38.

Dodd

KW, Guenther PM, Freedman LS, Subar AF, Kipnis V, et al. Statistical methods

for estimating usual intake of nutrients and foods: a review of the theory

(2006) J Am Diet Assoc 106:1640-1650 39.

Matsuto

SM, Matsuto VKR and Barros TLN. Impact of aging on anthropometric, neuromotor

and metabolic variables of physical fitness (2000) Braz J Sci Mov 4: 21-32. 40.

Slater

B. Development and validation of a semi-quantitative food frequency

questionnaire for adolescents 2001 [doctoral dissertation]. São Paulo: School

of Public Health, University of São Paulo. 41.

Mahan

LK, Escott-Stump S, and Gee M. Body Weight Control: food nutrition and diet

therapy (2010) Elsevier 5: 532-562. 42.

Bernardi

F, Cichelero C and Vitolo MR. Dietary restriction behavior and obesity (2005)

Rev Nutr 8: 1. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1415-52732005000100008

43.

World

Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic.

Report of a World Health Organization Consultation. Geneva: World Health

Organization 2000 256. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021932003245508

44.

Latin

American Consensus on Obesity. Montevideo 1998. 45.

Willett

WC, Dietz WH and Colditz GA. Guidelines for health weight (1999) N Eng J Med 6:

427-434. https://10.1056/NEJM199908053410607

46.

Amorim

MMA, Santana NES, Souza AH and Santiago MC. Client adherence to nutritional

obesity treatment in a school clinic (2018) Diabetes Updates 1: 1- 9. https://doi.org/10.15761/du.1000109

Maria Marta Amancio Amorim, PhD in Nursing,

Professor at the Unifacvest University Center, Brazil,

Email: martamorim@hotmail.com Amancio Amorim

MM, Silva AG, Medeiros Lopes CS, Gonçalves Santos MAT and Souza HA. Nutritional

profile of clients with obesity treated at the school clinic (2019) J Obesity

and Diabetes 3: 45-49. Obesity, Eating habits, Nutritional assessment.Nutritional Profile of Clients with Obesity Treated at the School Clinic

Abstract

Introduction:

Obesity can be conceptualized in a simplified way, as a condition of abnormal

or excessive accumulation of fat in the body. Objective: To characterize the

nutritional profile of the clients with obesity treated at the Integrated

Clinic of Health Care at UNA University Center, Belo Horizonte, Brazil. Full-Text

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Results

Discussion

Conclusion

Acknowledgement

References

*Corresponding

author

Citation

Keywords