Research Article :

Mahfuj-Ul-Anwar,

Sajeda Afrin, ASM Rahenur Mondol, Mohammad Nurul Islam

Khan, Narayan Chandra Sarkar, Mohammad Kumruzzaman Sarker,

Shah Md Sarwer Jahan, Moni Rani and Ratindra Nath Mondal Background: Stroke is a leading cause of mortality and

disability worldwide. To prevent complications and permanent defects, early

diagnosis, distinguishing the type and risk factor of stroke is crucial. Methodology: It was a hospital based

cross sectional study, purposive sampling method was used, and a total of 469

stroke patients admitted into Department of Medicine, Rangpur medical college

hospital, Bangladesh were included in this study. Results: In this study we have studied of 469 acute stroke

patients. Among them 81% (380) were ischemic stroke patients and 19% (89) were

hemorrhagic stroke. Overall male were more than female 308 (65.7%) vs

161(34.4%). The mean age for the ischemic stroke group was 64.1 ± 10.9 years,

which was significantly higher than that of the hemorrhagic group (59.8 ± 9.60years)

(P<0.05). Acute hemorrhagic stroke patients presented with acute onset of

focal neurological deficit 61.8%, headache 64%, vomiting 59.6%, alteration of

consciousness 48.3% and convulsion 27%. On the other hand, acute ischemic

stroke patient presented with alteration of consciousness 65.5%, acute onset of

focal neurological deficit 39.5%, paralysis 41%, deficit after awakening 32.4%

and aphasia 34.7%. Among the risk factors of stroke in acute ischemic stroke

patients hypertension was 59.2%, diabetes mellitus 20%, history of previous

stroke 16.1%, ischemic heart disease 14.5% and atrial fibrillation 10.3% were

present, on the other hand in acute hemorrhagic stroke patients hypertension

76.4%, smoking 70.8% and diabetes mellitus 6.7% were present. 26.97% of the

acute hemorrhagic stroke and 13.9% of the acute ischemic stroke patients died

in hospital. Conclusion: Common

presentation of stroke was acute onset of focal neurological deficit; headache

and vomiting were more in hemorrhagic stroke patient; alteration of

consciousness, paralysis was predominant in ischemic stroke patient Stroke

was defined according to WHO criteria as rapidly developing clinical signs of

focal (at times global) disturbance of cerebral function lasting more than 24 hours

or leading to death with no apparent cause other than that of vascular origin.

Two types of brain stroke are hemorrhagic and ischemic. Hemorrhagic stroke,

which is due to blood vessel rupture, accounts for 20% of CVAs. Ischemic stroke

due to brain vessels occlusion and blockage includes 80%. Stroke is a leading

cause of mortality and disability worldwide and the economic costs of treatment

and post-stroke care are substantial. Results from the 2015 iteration of the

Global Burden of Diseases (GMD), Injuries, and Risk Factors Study (RFS) showed

that although the age-standardized death rates and prevalence of stroke have

decreased over time, the overall burden of stroke has remained high, with more

than 80 million [1-4]. Stroke

survivors in 2016. In 2016, stroke was the second largest cause of death globally

(5.5 million deaths) after ischemic heart disease. Stroke was also the second

most common cause of global Disability-Adjusted Life-Years DALYs (116.4

million). There were 80.1 million prevalent cases of stroke globally in 2016

and 13.7 million new stroke cases in 2016. In 2016 the number of stroke patient

and death due to stroke in Bangladesh were 161,709 and 126,369 respectively. In

order to prevent complications and permanent defects, early diagnosis is the

key in stroke patients; however, distinguishing the type of stroke plays a

crucial role in patient care. The management of a patient with acute stroke is

based on the knowledge of stroke type: hemorrhagic or ischemic. In most

developed countries, diagnosis is easily obtained by CT scanning, which allows

the accurate Distinction of hemorrhagic and ischemic types [5,6]. However,

quick access to CT scanning is not available in every country and hospital

which may lead to loss of treatment golden time. Simple clinical findings are

helpful in distinguishing the type of stroke, but need for diagnostic imaging is

an undeniable fact. According to this issue, many studies described various

clinical findings especially neurological signs and symptoms and risk factors

differentiation, and some of them presented formulas to distinguish stroke

types based on clinical evaluations. As populations age and low-income and

middle-income countries go through the epidemiological transition from

infectious to non-communicable diseases as the predominant cause of morbidity,

together with concomitant increases in modifiable risk factors, it is expected

that the burden of stroke will further increase until effective stroke

prevention strategies are more widely implemented [7-14]. About

90% of the stroke burden is attributable to modifiable risk

factors, with about 75% being due to behavioral factors such as smoking,

poor diet and low physical activity. Achieving control of behavioral and

metabolic risk factors could avert more than three quarters of the global

stroke burden. Since treatment measures for stroke are still rather limited and

expensive, in a high prevalent country like Bangladesh, it is important to be

familiar with relative contribution of different stroke risk factor in an

individual patient. The individuals with a relatively high risk profile can

take steps to modify their risk factors through lifestyle changes and/or

medical treatment. Healthy lifestyle modification and better adherence to

recommended medications via an affordable multidrug

polypill containing blood pressure and lipid-lowering medications, early

initiation of antiplatelet drugs after ischemic stroke could potentially also

enable cost-effective prevention of stroke globally, potentially halving stroke

incidence and mortality [15-18]. In

addition to prevention efforts, appropriate acute and long-term treatment is

essential, given the high recurrence rate of stroke. Similarly, public

awareness programs aimed at increasing the recognition of stroke warning signs

and altering modifiable risk factors can be designed to address the high-risk

groups. Because the pathogenesis of ischemic stroke is different from that of

hemorrhagic stroke, their clinical factors including risk factors would not be

the same. This study was undertaken to assess the difference in risk factors,

clinical and laboratory profiles in hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke patients so

as to provide some scientific evidence for stroke prevention in Bangladesh

[19-21]. This

was a hospital based cross sectional study was conducted in Department of

Medicine, Rangpur medical college hospital, Rangpur, Bangladesh from January

2010 to December 2011. Purposive sampling method was used. The study included

469 patients with acute stroke diagnosed by history, clinical findings and

confirmed by CT scan of brain within 1week of attack. Patients with no

definitive CT scan results or those suspected to have transient ischemic

attacks were excluded from the study. For each patient, demographic data, type

of stroke, risk factors, clinical and initial laboratory variables and

in-hospital death were recorded. Demographic variables included age and sex. Types

of stroke included ischemic and hemorrhage. Risk

factors included a history of Hypertension (HTN), Diabetes Mellitus (DM), Ischemic

Heart Disease (IHD), Valvular

Heart Disease (VHD), Atrial Fibrillation (AF), Renal Impairment (RI), Smoking,

Obesity (SO), advanced age (>80 years), previous stroke and family history

of stroke, hypertension, Diabetes Mellitus (DM) and Coronary Artery Disease (CAD).

Patient outcome included vital status at discharge (alive or dead). All

patients were investigated with routine investigations such as TC, DC, ESR,

Hb%, total platelet count, urine examination, RBS (on admission blood sugar

level), FBS and 2HABF, fasting lipid profile, serum electrolytes, serum

creatinine, ECG. CT scan of brain was done in every case to confirm the

diagnosis. Treatment was given accordingly and inpatient outcome were observed.

The clinical factors to be observed in this study included advanced age (>80

years), gender (male-exposure), cigarette smoking (average smoking ≥ 1

cigarettes per day, and continued more than one year). Hypertension was

diagnosed when the blood pressure measured in the hospital was >140/90 mmHg

or if the patient was taking antihypertensive agents. Diabetes was diagnosed if

a patient was using oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin and or post-stroke

repeated fasting plasma glucose levels ≥ 7.0 mmol/L (≥ 126 mg/dL) and 2 hours

after glucose level ≥ 11.1mmol/L (≥ 200mg/dl) and or the glycosylated

hemoglobin level exceeded 6.5%. Obesity

was defined based on the body mass index (BMI) value; males and females with

BMI >30 were considered to be obese. On admission laboratory reports

includes increased white blood cell (WBC>11.0×109/L), hypertriglyceridemia

(triglyceride (TG)>1.7 mmol/L), hypercholesterolemia (total cholesterol (TC)

≥ 5.7 mmol/L), low level of high-density lipoproteins (HDL<1.0 mmol/L), ischemic

changes or arrhythmia on ECG. All relevant information was recorded in a

predesigned questionnaire. Collected data were compiled and appropriate

analyses were carried out using computer-based software, Statistical Package

for Social Science (SPSS)-17. The continuous clinical variants were compared by

unpaired Student's t test. The Chi-square test was used to evaluate differences

in proportion of clinical factors in patients between ischemic and hemorrhagic

stroke. A P value <0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically

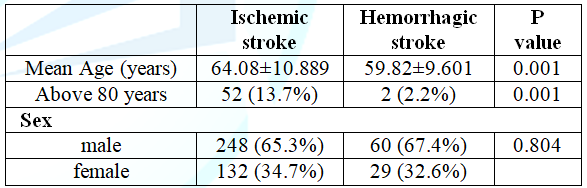

significant. Table 1: Comparison of the age of patients (in percentage) with ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Acute

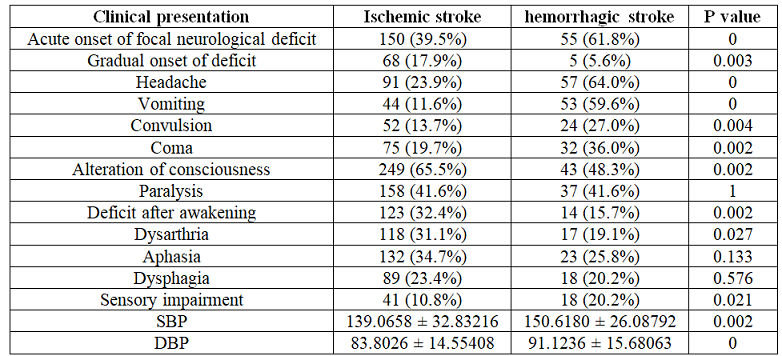

hemorrhagic stroke patients presented with acute onset of focal neurological

deficit 61.8%, headache 64%, vomiting 59.6%, alteration of consciousness 48.3%

and convulsion 27%. On the other hand, acute ischemic stroke patient presented

with alteration of consciousness 65.5%, acute onset of focal neurological

deficit 39.5%, paralysis 41%, deficit after awakening 32.4% and aphasia 34.7%.

Clinical

presentations of two subtypes of stroke were detailed in (Table 2). Among

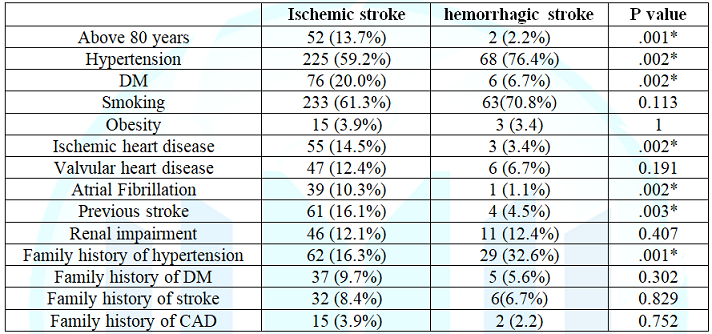

the risk factors of stroke in acute ischemic stroke patients hypertension was

59.2%, diabetes

mellitus 20%, history of previous stroke 16.1%, ischemic heart disease

14.5% and atrial fibrillation 10.3% were present, on the other hand in acute

hemorrhagic stroke patients hypertension 76.4%, smoking 70.8% and diabetes

mellitus 6.7% were present. (Table 3)

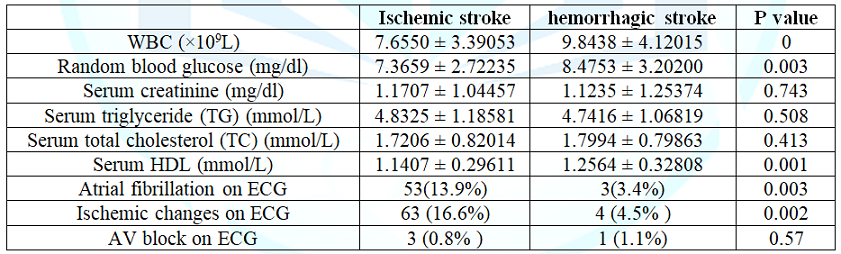

showing risk factors of the ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke) the laboratory

data of patients with ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke were compared at (Table 4). Atrial fibrillation and

ischemic changes on ECG was more in ischemic stroke than hemorrhagic stroke,

13.9% vs 3.4% and 16.6% vs 4.5% respectively. 26.97% of the acute hemorrhagic

stroke and 13.9% of the acute ischemic stroke patients died in hospital. Table 2: Comparison of clinical presentations on admission of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Table 3: Comparison of risk factors of the ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. In

our study 81% patients were ischemic stroke, similar findings observed in other

studies. Observed higher rates of ischemic stroke incidence suggests that

ischemic stroke patients have a great exposure to modifiable risk factors which

can be controlled through lifestyle modification and appropriate treatment thus

can prevent a large proportion of such incidence of stroke. Stroke (both

ischemic and hemorrhagic) is more common in men than women, our study also

found similar result. Lifestyle differences, such as cigarette smoking and

alcohol drinking, may help explain this sex disparity. In addition, there is no

vascular protection of endogenous estrogen in males and it may contribute to

the risk of stroke in men. In the current study, mean age of patients with

ischemic stroke was higher than hemorrhagic

stroke patients, similar findings observed in many of the other studies Knowledge

on the relative contribution of risk factors in hemorrhagic versus ischemic

strokes is still insufficient. Some risk factors are common for both hemorrhagic

and ischemic stroke. In our study factors favoring ischemic stroke as opposed

to hemorrhagic [22-29]. Strokes

were diabetes, atrial fibrillation, history of previous stroke and increasing

age. Hypertension and family history of hypertension favored hemorrhagic stroke

as opposed to ischemic stroke. In our study smoking, obesity, Valvular Heart

Disease (VHD), renal impairment, family history of DM, stroke or coronary

artery disease favored neither of the stroke types. In a large study based on

394, 84 patients’ well-established risk factors and markers of atherosclerotic

and occlusive arterial disease such as diabetes, atrial fibrillation, previous

myocardial infarction, previous stroke and intermittent arterial claudication

were associated with ischemic stroke rather than hemorrhagic stroke smoking and

high alcohol intake favored hemorrhagic stroke, whereas age, sex, and

hypertension did not herald stroke type. In the hospital-based Lausanne Stroke

registry (n=3901) smoking, hypercholesterolemia, migraine, previous transient ischemic

attack, atrial fibrillation, and heart disease favored ischemic stroke, whereas

hypertension was the only significant factor related to hemorrhagic vs ischemic

stroke. Hypertension is the most prevalent risk factor for stroke, based on

data from 30 studies, and has been reported in about 64% of patients with

stroke. High blood pressure can [30-33]. significantly increase the risk of a

hemorrhagic stroke. This risk is even more pronounced in the elderly, in people

who smoke, in men, in diabetics, and in people who drink alcohol. In our study

59.2% of the ischemic

stroke and 76.4% of the hemorrhagic stroke patient had hypertension. Recent

large-scale, international population studies suggest that diabetes is one of

the most Important modifiable risk factors for cerebrovascular disease.

Diabetes is also a well-established independent risk factor for ischemic stroke.

Diabetes causes various microvascular and macrovascular changes often Cerebral

Small Vessel Diseases (CSVD) and ultimately develops ischemic stroke. Cigarette

smoking has long been recognized as major risk factors for stroke. The

pathophysiological effects are multifactorial, involving both systemic vasculature

and blood rheology. So far it is still controversial whether the effects of

cigarette smoking on ischemic stroke are consistent with those on hemorrhagic

stroke (Clinical factors in patients with ischemic versus hemorrhagic stroke in

East China). The data from our study exhibited that the association of smoking

with hemorrhagic stroke was approximately the same as that with ischemic

stroke, similar result also found in previous studies [34-45]. Dyslipidemia

have traditionally been regarded as a risk factor for coronary artery disease

but not for cerebrovascular disease. However, recent studies have clarified the

relationship between lipids and ischemic stroke, and showed that the risk of

ischemic stroke. In a large cohort of elderly patients, low triglycerides

levels were associated with an increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke. In our

study, we observed a low level of Clinical

features, such as acute onset, headache, vomiting, convulsion, increased

systolic and diastolic blood pressure on admission, decreased consciousness and

coma were significant in patients with hemorrhagic stroke than ischemic stroke

patients reported by others our study also found similar result. Severity of

the clinical features in hemorrhagic stroke presumably due to increased

intracranial pressure and the direct compression or distortion of the thalamic

and brain-stem reticular activating system, expansion of hematoma, worsening

cerebral edema and meningismus resulting from blood in ventricles. On the other

hand gradual onset, deficit after awakening, focal deficits, visual field

defect and sensory impairment were significant in patients with ischemic stroke

also observed previously, however, occurrence site of these signs depends on

the brain area that is being nourished by suffering vessels. On initial investigations

like previous studies WBC, Blood Glucose (BG), HDL, were higher in the

hemorrhagic group than in the ischemic group. On the other hand ischemic

changes and atrial fibrillation8 on ECG is significantly observed in ischemic

stroke patients. Our study findings are consistent with all those studies.

Moreover, a previous study reported a significant elevation of the WBC count in

ICH was associated with deteriorating level of consciousness, cerebral

vasospasm and death. Increased WBC count is mainly attributed to enhanced

catecholamine and corticosteroid release because of an extension of the blood

into the subarachnoid space, but the inflammatory response of ventricular

extension (ventriculitis) may be an additional contributing. Factor So, WBC

count may. Be one of the important prognostic markers in hemorrhagic stroke

patients. Hospital mortality is higher in hemorrhagic stroke than ischemic

stroke. Ratindra et al found short term. (Within 28 days) mortality in

hemorrhagic stroke 45.5%, where hospital mortality was 40% and in ischemic

stroke 18.1% and hospital mortality was 7.97%. Our study found similar result [51-61].

Proper

stroke management depends on the distinction between intracerebral hemorrhage

and cerebral infarction. Whilst CT imaging remains the gold standard for

differential diagnosis, availability of this important diagnostic tool is not

always feasible. Despite the lack of absolute accuracy of classification

models, adequate knowledge on risk factors, clinical features and initial

investigations may contribute to such a differentiation of cerebral infarction

from intracerebral

hemorrhage in order to aid clinicians to decide about starting antiplatelet

therapy in settings where rapid access to Computed Tomography (CT) is lacking

[8]. Nevertheless, a combined analysis of 40000 randomized patients from the

Chinese Acute Stroke Trial (CAST) has demonstrated that early aspirin use

(within 48 hours of onset) amongst the 9000 patients (22%) randomized without a

prior CT scan appeared to be of net benefit with no unusual excess of

hemorrhagic stroke. Moreover, even amongst the 800 subjects (2%) whose

presenting event was subsequently discovered to have been a hemorrhagic stroke,

there was no evidence of detrimental effect of aspirin (OR 0.86 for further

stroke or death, 63 aspirin versus 67 control). Because in CAST and IST trials

the incidence of hemorrhagic stroke or transformation was low during the first

day from the event, whereas that of recurrent ischemic stroke was relatively

high, early aspirin use is justifiable when ischemic stroke is suspected and

rapid CT scanning is lacking [62-64].Clinical Features, Risk Factors and Hospital Mortality of Acute Stroke Patients

Abstract

Full-Text

Introduction

Materials

and Methods

Results

In

this study we have studied of 469 acute stroke patients. Among them 81% (380)

were ischemic stroke patients and 19% (89) were hemorrhagic stroke. Overall

male were more than female 308 (65.7%) vs 161 (34.4%) and also in both types of

stroke patients (ischemic stroke group 65.3% and 67.4% of the hemorrhagic

group). The mean age for the ischemic stroke group was 64.08 ± 10.89 years,

which was significantly higher than that of the hemorrhagic group (59.82 ± 9.60years)

(P<0.05). (Table 1) shows the details.

Discussion

Conclusion

Common presentation of stroke was acute onset of

focal neurological deficit; headache and vomiting was more in hemorrhagic

stroke patient; alteration of consciousness, paralysis was predominant in

ischemic stroke patient.

1. Aho

K, Harmsen P, Hatano S, Marquardsen J, Smirnov VE, et al. Cerebrovascular

disease in the community: results of a WHO collaborative study (1980) Bull

World Health Organ 58: 113-130.

2. Marx

J, Hockberger R, Walls R. Rosen's Emergency Medicine (2006) Elsevier, Netherlands

3. Tntinalli

JE, Kelen GD and Stapczynski JS. Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study

Guide (2004) Mc raw-hill, USA

4. Rajsic

S, Gothe H, Borba HH, Sroczynski G, Vujicic J, et al. Economic burden of

stroke: a systematic review on post-stroke care (2018) Eur J Health Econ 20:

107-134.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-018-0984-0 .

5. Feigin

VL, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, Abd-Allah F, Abdulle AM, et al. Global, regional,

and national burden of neurological disorders during 1990-2015: a systematic

analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015 (2017) Lancet Neurol 16:

877-897. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30299-5

6. Johnson

COJ, Nguyen M, Roth EA, Nichols E, Alam T, et al. Global, regional, and national

burden of stroke, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of

Disease Study 2016 (2019) Lancet Neurol 18: 439-458.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30034-1

7. Besson

G, Robert C, Hommel M and Perret J. Is it clinically possible to distinguish

nonhemorrhagic infarct from hemorrhagic stroke? (1995) Stroke 26: 1205-1209.

https://doi.org/10.1161/01.

STR.26.7.1205

8. Efstathiou

SP, Tsioulos DI, Zacharos ID, Tsiakou AG, Mitromaras AG, et al. A new

classification tool for clinical differentiation between haemorrhagic and

ischaemic stroke (2002) J Intern Med 52: 121-129. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.01013.x

9. Ojaghihaghighi

HS, Vahdat SS, Mikaeilpour A and Ramouz A. Comparison of neurological clinical

manifestation in patients with hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke (2017) World J

Emerg Med 8: 34-38. https://dx.doi.org/10.5847%2Fwjem.j.1920-8642.2017.01.006

10. Williams GR, Jiang JG, Matchar DB and Samsa GP. Incidence and occurrence of total (first-ever and recurrent) stroke (1999) Stroke 30: 2523-2528.

https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.30.12.2523

11. Smith RW, Scott PA, Grant RJ, Chudnofsky CR and Frederiksen SM. Emergency physician treatment of acute stroke with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator: a retrospective analysis (1999) Acad Emerg Med 6: 618-625.

12. Lewandowski

CA, Frankel M, Tomsick TA, Broderick J, Frey J, et al. Combined intravenous and

intra-arterial r-TPA versus intra-arterial therapy of acute ischemic stroke: emergency

management of stroke (EMS) bridging trial (1999) Stroke 30: 2598-2605.

https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.30.12.2598

13. Khan

J and Rehman A. Comparison of clinical diagnosis with computed tomography in

ascertaining type of stroke (2005) J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 17: 65-67.

14. Celani

MG, Righetti E, Migliacci R, Zampolini M, Antoniutti L, et al. Comparability

and validity of two clinical scores in the early differential diagnosis of

acute stroke (1994) BMJ 308: 1674-1676. https://dx.doi.org/10.1136%2Fbmj.308.6945.1674

15. Yan

LL, Li C, Chen J, Luo R, Bettger J, et al. Cardiovascular, respiratory, and

related disorders (2017) Prabhakaran D (ed), Anand S (ed), Gaziano TA (ed). USA

16. Wajngarten

M and Sampaio GS. Hypertension and Stroke: Update on Treatment (2019) Eur

Cardiol 14: 111-115. https://dx.doi.org/10.15420%2Fecr.2019.11.1

17. Feigin

VL, Roth GA, Naghavi M, Parmar P, Krishnamurthi R, et al. Global burden of

stroke and risk factors in 188 countries, during 1990-2013: a systematic

analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013 (2016) Lancet Neurol 15:

913-1924. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30073-4

18. Riaz

BK, Chowdhury SH, Karim MN, Feroz S, Selim S, et al. Risk factors of

hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke among hospitalized patients in Bangladesh a

case control study (2015) Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull 41: 29-34.

19. Feigin VL, Norrving B, George MG, Foltz JL, Roth GA, et al. Prevention of stroke: a strategic global imperative (2016) Nat Rev Neurol 12: 501-512.

20. Gaziano

TA, Opie LH and Weinstein MC. Cardiovascular disease prevention with a

multidrug regimen in the developing world: a cost-effectiveness analysis (2006)

Lancet 368: 679-686.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(06)69252-0

21. Brainin M, Feigin V, Martins S, Matz K, Roy J, et al. Cut stroke in half: polypill for primary prevention in stroke (2018) Int J Stroke 13: 633-647.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1747493018761190

22. Zhang J, Wang Y, Wang GN, Sun H, Shi JQ, et al. Clinical factors in patients with ischemic versus hemorrhagic stroke in East China (2011) World J Emerg Med 2: 18-23.

23. Andersen

KK, Olsen TS, Dehlendorff C and Kammersgaard LP. Hemorrhagic and ischemic

strokes compared stroke severity, mortality, and risk factors (2009) Stroke 40:

2068-2072.

https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.108.540112

24. Mozaffarian

D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, et al. Heart disease and stroke

statistics-2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association (2015)

Circulation 131: e29-e322.

https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152

25. Riaz

BK, Chowdhury SH, Karim MN, Feroz S, Selim S, et al. Risk factors of hemorrhagic

and ischemic stroke among hospitalized patients in Bangladesh a case control

study (2015) Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull 41: 29-34.

https://doi.org/10.3329/bmrcb.v41i1.30231

26. Massaro

AR, Sacco RL, Scaff M and Mohr JP. Clinical discriminators between acute brain hemorrhage

and infraction (2002) Arq Neuropsiquiatr 60: 185-191.

https://doi.org/10.1590/S0004-282X2002000200001

27. Perna

R and Temple J. Rehabilitation outcomes: ischemic versus hemorrhagic strokes (2015)

Behavioural Neurology 2015: 891651.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/891651

28. Oh JS, Bae HG, Oh HG, Yoon SM, Doh JW, et al. The changing trends in age of first-ever or recurrent stroke in a rapidly developing urban area during 19 years (2017) J Neurol Neurosci 2: 206.

http://dx.doi.org/10.21767/2171-6625.1000206

29. Benjamin

EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, et al. Heart disease and stroke

statistics-2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association (2017) Circulation

135: e146-e603.

https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000485

30. Qureshi AI, Tuhrim S, Broderick JP, Batjer HH, Hondo H, et al. Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (2001) N Engl J Med 344: 1450-1460.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200109063451014

31. Ferro JM. Update on cerebral haemorrhage (2006) J Neurol 253: 985-999.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-006-0201-4

32. Ha¨nggi D and Steiger HJ. Spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage in adults: a literature overview (2008) Acta Neurochir 150: 371-379.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00701-007-1484-7

33. Liu

XF, van Melle G and Bogousslavsky J. Analysis of risk factors in 3901 patients

with stroke (2005) Chin Med 20: 35-39.

34. Feigin

VL, Norrving B and Mensah GA. Global burden of stroke (2017) Circ Res 120:

439-448.

https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.116.308413

35. An SJ, Kim TJ and Yoon BW. Epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical features of intracerebral hemorrhage: an update (2017) J Stroke 19: 3-10.

https://dx.doi.org/10.5853%2Fjos.2016.00864

36. Harvard Medical

School. Hemorrhagic stroke. February 2019.

37. Burton JK, Quinn TJ and Fisher M. Diabetes and stroke (2019) 36: 4.

https://doi.org/10.1002/pdi.2230

38. The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration. Diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose concentration, and risk of vascular disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of 102 prospective studies (2010) Lancet 375: 2215-2222.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60484-9

39. Arboix

A, Morcillo C, García-Eroles L, Massons J, Oliveres M, et al. Different

vascular risk factor profiles in ischemic stroke subtypes: The SagratCor Hospital

of Barcelona Stroke Registry (2000) Acta Neurol Scand 102: 264-270.

https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-404.2000.102004264.x

40. Arabadzhieva

D, Kaprelyan A, Georgieva Z, Tsukeva A, et al. Diabetes mellitus as a risk

factor for ischemic stroke (2014) Science and Technologies 4: 27-30.

41. Khoury

JC, Kleindorfer D, Alwell K, Moomaw CJ, Woo D, et al. Diabetes mellitus: a risk

factor for ischemic stroke in a large biracial population (2013) Stroke 44: 1500-1504.

https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.113.001318

42. Shi Y and Wardlaw JM. Update on cerebral small vessel disease: a dynamic whole-brain disease (2016) Stroke Vasc Neurol 1: 83-92.

https://dx.doi.org/10.1136%2Fsvn-2016-000035

43. Ariesen

MJ, Claus SP, Rinkel GJE and Algra A. Risk factors for intracerebral hemorrhage

in the general population: a systematic review (2003) Stroke 34: 2060-2066.

https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.0000080678.09344.8d

44. Kurth

T, Kase CS, Berger K, Schaeffner ES, Buring JE, et al. Smoking and the risk of

hemorrhagic stroke in men (2003) Stroke 34: 1151-1155.

https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000065200.93070.32

45. turgeon

JD, Folsom AR, Longstreth WT, Shahar E, Rosamond WD, et al. Risk factors for

intracerebral hemorrhage in a pooled prospective study (2007) Stroke 38: 2718 -2725.

https://doi.org/10.1161/strokeaha.107.487090

46. de

Craen AJ, Blauw GJ, Westendorp RG. Cholesterol and risk of stroke: cholesterol,

stroke, and age (2006) BMJ 333: 148.

https://dx.doi.org/10.1136%2Fbmj.333.7559.148

47. Smith

EE, Abdullah AR, Amirfarzan H and Schwamm LH. Serum lipid profile on admission

for ischemic stroke: failure to meet national cholesterol education program

adult treatment panel (NCEP2ATPIII) guidelines (2007) Neurology 68: 660-665. https://doi.org/10.1212/01.wnl.0000255941.03761.dc

48. Bonaventure

A, Kurth T, Pico F, Barberger-Gateau

P, Ritchie K, et al. Triglycerides and risk of hemorrhagic stroke vs. ischemic

vascular events: The Three-City Study (2010) Atherosclerosis 210: 243-248.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.10.043

49. Huisman

MV, Lip GY, Diener HC, Halperin JL, Rothman KJ, et al. Design and rationale of

Global Registry on Long-Term Oral Antithrombotic Treatment in Patients with

Atrial Fibrillation: a global registry program on long-term oral antithrombotic

treatment in patients with atrial fibrillation (2014) Am Heart J 167: 329-334.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2013.12.006

50. Hart

RG, Pearce LA and Aguilar MI. Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent

stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (2007) Ann Intern

Med 146: 857-867.

https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-146-12-200706190-00007

51. Aring CD and Merritt HH. Differential diagnosis between cerebral hemorrhage and cerebral thrombosis: a clinical and pathologic study of 245 cases. (1935) Arch Intern Med 56: 435-456.

https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1935.00170010023002

52. Bogousslavsky

J, van Melle G and Regli F. The Lauanne Stroke Registry: analysis of 1000

consecutive patients with first stroke (1988) Stroke 19: 1083-1092.

https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.19.9.1083

53. Mohr

JP, Caplan LR, Melski JW, Goldstein

RJ, Duncan GW, et al. The harvard cooperative stroke registry: a prospective

registry (1978) Neurology 28: 754-762.

https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.28.8.754

54. Melo

TP, Pinto AN and Ferro JM. Headache in intracerebral hematomas (1996) Neurology

47: 494-500.

https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.47.2.494

55. Davis PH, Dambrosia JM, Schoenberg BS, Schoenberg DG, Pritchard DA, et al. Risk factors for ischemic stroke: a prospective study in Rochester, Minnesota (1987) Ann Neurol 22: 319-327.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.410220307

56. Fogelholm R, Murros K, Rissanen A and Ilmavirta M. Factors delaying hospital admission after acute stroke (1996) Stroke 27: 398-400.

https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.27.3.398

57. Kothari R, Hall K and Brott T. Early stroke recognition: developing an out-of-hospital NIH Stroke Scale (1997) Acad Emerg Med 4: 986-990.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.1997.tb03665.x

58. Dávalos A, Castillo J, Martinez-Vila E, Delay in neurological attention and stroke outcome cerebrovascular diseases study group of the Spanish society of neurology (1995) Stroke 26: 2233-2237.

59. Jorgensen HS, Nakayama H, Reith J, Raaschou HO, Olsen TS, et al. Factors delaying hospital admission in acute stroke: the Copenhagen Stroke Study (1996) Neurology 47: 383-387.

60. Neil-Dwyer G and Cruickshank J. The blood leukocyte count and its prognostic significance in subarachnoid haemorrhage (1947) Brain 97: 79-86.

https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/97.1.79

61. Suzuki S, Kelley RE, Dandapani BK, Reyes-Iglesias Y, Dietrich WD, et al. Acute leukocyte and temperature response in hypertensive intracerebral haemorrhage (1995) Stroke 26: 1020-1023.

https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.26.6.1020

62. Mondal

RN, Barman S, Islam MJ, Jahan SMS, Alam ABMM, et al. Short-term predictors of

mortality among patients with hemorrhagic stroke (2014) World Heart J 6: 273-282.

63. Mondal

RN, Jamal M, Islam MA, Anwar MM, Rahman MM, et al. Short term outcome of acute

ischemic stroke patients (2020) EC Cardiology 7: 10-18.

64. Chen ZM, Sandercock P, Pan HC, Counsell C, Collins R, et al. Indications for early aspirin use in acute ischemic stroke: a combined analysis of 40000 randomized patients from the Chinese acute stroke trial and the international stroke trial (2000) Stroke 31: 1240-1249.

https://doi.org/10.1161/01.str.31.6.1240

Dr. Ratindra Nath Mondal, Society of General Physicians and Daktarkhana (GP

center) Rangpur, Bangladesh, Email: dr.ratinmondal@gmail.com

Anwar-Ul-M, Afrin S, Mondol RASM, Khan MNI, Sarkar CS, et al. Clinical features, risk factors and hospital mortality of acute stroke patients (2020) J Obesity and Diabetes 4: 9-14.

Ischemic, Hemorrhagic, Stroke, Rangpur, Bangladesh.