Research Article :

Vaartio-Rajalin

Heli, Mattjus Camilla, Nordblad John and

Fagerström Lisbeth Aim: To describe the

development and outcomes of a rehabilitation intervention for persons with

Parkinson’s and their near-ones. Material and methods: Customer-understanding-based

intervention development; and a pilot study: a random sample of persons with PD

(n=18) and their near-ones (n=7) were divided into subgroups: Persons with PD,

Gym rehabilitation; Persons with PD, Home rehabilitation; Near-ones, Gym

rehabilitation; Near-ones, Home rehabilitation. Data included clinical

measurements, scores from a PDQ-39 questionnaire and a simple diary, analyzed

with descriptive statistics. Results: The PISER intervention was

established to be feasible in relation to study and data collection procedures,

outcome measures and to recruitment of persons with PD. After the eight-week

intervention, both Persons with PD subgroups and Near-ones in Gym group had

better clinical outcomes and better emotional, social and communicative

health-related quality of life. Near-ones, Home rehabilitation had marginally

poorer clinical outcomes, but still reported better cognitive well-being. Conclusions:

The PISER intervention was shown to be feasible. By engaging in systematic

physical activity, persons with PD and near-ones maintained or developed their

functional capacity, psychosocial well-being and certain aspects of

health-related quality of life. An eight-week rehabilitation intervention had a

positive impact on self-management, especially in gym-groups, in which the

participants enjoyed the social aspects of group rehabilitation and received

individual instruction and feedback during physical activity. This kind of

person-centered, systematic physical activity intervention may prevent

inactivity and fall risks, and delay onset of activity limitations. It is vital

that healthcare professionals and clients with PD together analyze and discuss

the meaning of physical activity and self-rehabilitation. Parkinson’s

Disease (PD) is the second most common age-related neurodegenerative

disorder after Alzheimer’s disease. To date, approximately ten million persons

throughout the world have been diagnosed with PD, and the majority are males

aged 55 or older [1,2]. There is no single known cause of PD, but some genetic

and environmental factors have been identified [3]. Despite the disorder’s

chronic nature, the age and mode of onset, prominence of symptoms, rate of

progression and resultant degree of impairment differ greatly between

individuals. The diagnosis of PD usually occurs after an extended

period of time, because the disease includes an initial asymptomatic phase

followed by a non-specific, prodromal phase. At the time of diagnosis, persons

with PD can already be experiencing severe limitations in Activities of Daily

Living (ADL) and a decreased Quality

of Life (QoL), and are thus in immediate need of rehabilitation [4]. If

rehabilitation is started immediately, and especially if the care and

rehabilitation given are systematic, holistic, person-centered, and

inter-professional, persons with PD can achieve a similar QoL as same-aged

individuals without PD [5]. Still, to achieve such benefits from

rehabilitation, persons with PD need to develop long-term exercise habits. It

is beneficial to take individual preferences into account, because a person is

most likely to continue with an exercise regimen if it is enjoyed [6].

Intrinsic motivation is also important for long-term adherence [2]. Not only persons with PD but also their near-ones

(i.e., spouses, other family members) can experience strain and a poor QoL [7,8].

Researchers have seen that at-home rehabilitation becomes safer and truly

person-centered when near-ones are involved [6]. However, rehabilitation still

primarily occurs outside the home and without the inclusion of near-ones, even

though a home setting is suitable for the majority of rehabilitation activities

[9]. The aim of this study was to develop a person-centered, interactive,

systematic, effective rehabilitation intervention for persons with Parkinson’s

and their near-ones. In this article, we delineate and present the pilot

intervention, its´ feasibility and outcomes. Parkinson´s disease is a multifaceted, neurodegenerative,

chronic disorder affecting both motoric and voluntary movements, such as

dual-task performance or gait. The cardinal signs of the disease, e.g.,

tremors, rigidity, bradykinesia and postural instability, are caused by a loss

of dopamine in the substantia nigra and associated nigrostriatal denervation.

PD is divided into two subtypes: tremor dominant and postural instability gait

difficulty [1,2]. A slowly proceeding autoimmune

condition, PD has five symptom-related stages. In stages 1-2, persons with

PD have mild or relatively mild signs of illness, relatively good functional

capacity and can independently manage everyday life. In stages 3-5, persons

with PD experience severe or very severe symptoms, impairment in functional

capacity and have an evident need for assistance and help [10]. Through an

active physical lifestyle and medication, PD symptoms can be alleviated and a

person’s functional capacity maintained or improved [1], especially for those

with early- or mid-stage PD [6]. However, for older persons, meaning in

everyday life and QoL are often more important than ability or disability per

se [11]. Parkinson´s disease also affects non-motoric functions, e.g., task

initiation and accomplishment, cognition, social skills, sleep, fatigue [1] and

psychological well-being [12]. Therefore, the perceived disability and

health-related QoL of persons with PD [13,14] should be systematically analyzed

during rehabilitation. Accordingly, an inter-professional, collaborative

approach to PD rehabilitation is important [15,16]. Healthcare professionals involved with PD care and

rehabilitation should act in a person-centered manner [2]. Person-centeredness

can be defined as respect for a person’s narratives, preferences, values and

needs, in which the person’s sense of self, lived experiences and relationships

(i.e., personal knowledge) are reflected, and demonstrating this respect by

safeguarding the partnership that exists in care through shared decision-making

and meaningful activities in a personalized environment [17-20].

Person-centeredness also includes respect for a patient’s autonomy and

self-determination capacity. It is made concrete through a trustful

relationship established during the planning and evaluation of care and

rehabilitation with a patient, and should moreover include the patient’s

near-ones [21]. It is important to encourage near-ones to play a decisive role

and continuously support and encourage the person with PD. Rehabilitation

should be carried out in a peaceful, relaxing environment [22], e.g., in the

patient’s home. The terms public and patient involvement [23] and

human-centered co-design [24] are considered indicators of person-centeredness

in research activities, e.g., the identification of research priorities,

participation in data collection or analysis, or commenting on research

reports. In a scoping review (n=67) with a focus on PD rehabilitation, the

majority of studies were seen to not include patient or near-one involvement in

the planning, conducting or evaluation of rehabilitation for persons with PD.

Instead, the rehabilitation focus lay on physical exercise forms with or

without digital devices (VR glasses, closed-loop sensory feedback, gamepads, or

telerehabilitation with visual feedback) through which immediate feedback was

provided. In that review, PD rehabilitation was seen to be focused on

physiological symptoms and functional capacity, not cognitive or psychosocial

well-being per se. While the effectiveness of rehabilitation through physical

activities was difficult to synthetize, physical exercise did appear to

decrease non-motoric symptoms and improve physical outcomes, ADL functions, and

well-being [9]. In this study, a human-centered co-design was used.

Such an approach entails an active partnership with customers (seen here as

persons with PD) for the purpose of designing or improving care (see SQUIRE

guidelines (https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/squire/),

service systems or programs [24]. For the purposes of this study, a service

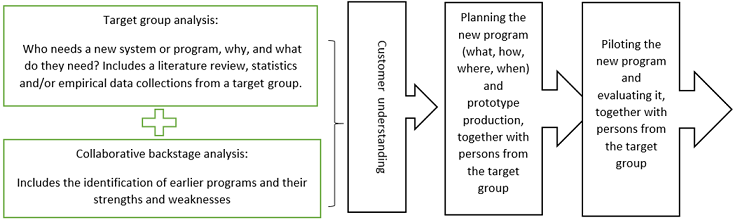

design [25] approach was applied (Figure 1). Figure 1: A service design process for PISER pilot intervention. In

Finland, there are approximately 16 000 persons with PD, but only about 60% of

them belong to any PD self-advocacy group. Some years ago, persons with PD

recommended the research idea investigated here to the faculty overseeing the

research, which can be considered public involvement. In their comments, they

noted that rehabilitation for persons with PD in Finland is quite unsystematic

and that there is a singular focus on rehabilitation centers. When starting

this research project, the research group sought to actively encourage persons

with PD and their near-ones to express own subjective interests and needs

regarding rehabilitation and be involved in the research and rehabilitation

intervention design. As

part of the service design approach used here, a customer understanding process

was started (autumn 2018, spring 2019). During collaborative meetings, an

evolving research group comprised of members from different professions and

perspectives (persons with PD, nursing researchers, registered nurses) and

others (rehabilitation organization staff, digital/virtual healthcare system

experts) discussed rehabilitation needs, strengths, weaknesses and

possibilities. A scoping review was also conducted at the same time, to

describe the existing knowledge on PD rehabilitation suitable for the home

environment, with digital devices if preferred [9]. Emanating from the

aforementioned meetings and the scoping review, a minor survey was conducted

that included persons with PD (n=10) and their near-ones (n=9 spouses) who had

participated in a week-long rehabilitation at a local rehabilitation center

spring 2019. The participants were asked to indicate their preferences

regarding various person-centered physical and psychosocial

rehabilitation activities available in-home or in the setting’s specific

geographical area. One could discern from the survey’s (non-published) findings

that the majority of participants were interested in weight training,

gymnastics, dance or yoga, and that opinion was divided over whether these

exercises should be undertaken alone in-home or as part of a group in a public

setting. Based

on the customer understanding findings and an evaluation of available and

realistic resources, a rehabilitation intervention called Person-centered,

Interactive, Systematic, Effective Rehabilitation (PISER) was planned. During

the intervention planning process, both the research group and the steering

committee for a local PD self-advocacy group sought financial support for the

pilot intervention. Some partners withdrew from the overall project at this

phase, likely because their organizations would not financially profit from the

collaboration. As a research group we were subsequently required to “re-think”

the parameters of the pilot intervention, and to employ a physiotherapist. The

research group developed a leaflet to describe the rehabilitation intervention,

including background, aim, timetable, voluntariness and anonymity issues. It

was determined that participation in the pilot intervention would be free of

charge, with all costs associated with the intervention financed through the

research project. Members of the steering committee for a local PD

self-advocacy group distributed the leaflet to persons with PD and their

spouses in the local area, through which voluntary participants were sought for

the pilot intervention during September 2019. In other words, this was a convenience

sample without a priori expectations about sample sizes. The only eligibility

criteria were a diagnosis of PD or the near relation to the person with PD

(spouse). One steering committee member maintained a list of those interested

in participating in the intervention, which took place October-November 2019 as

a block for all participants. For

the pilot study, the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2008)

have been followed. All those participating in the pilot intervention gave their

written informed consent. Comprised of both persons with PD and near ones, the

participants were asked prior to the start of the intervention to choose

whether they wished to be included in a gym rehabilitation group or implement a

rehabilitation program at home. For those choosing home rehabilitation, a

further choice was offered: the use of digital devices (e.g., VR glasses

offering ergonomic circumstances to look the Träning på recept© training

programs) or not. The participants themselves, therefore, decided on the

rehabilitation setting, in accordance with own preferences and social needs

instead of objective PD stage. Prior

to the start of the eight-week pilot intervention, the participants were asked

to come to the local gym setting for an individual meeting lasting

approximately 45 minutes. During the meeting, each participant was encouraged

to formulate a goal for him/herself during the intervention. A physiotherapist

conducted a standardized measurement of clinical functional capacity (M1, week

zero) and instructed participants in their choice of physical activities in

accordance with individual goals and the clinical measurements. Based on these,

the physiotherapist created personalized rehabilitation plans together with

each participant. The participants were then asked to complete a PDQ-39

questionnaire, which is a 39-item Parkinson

Disease Questionnaire that measures perceived health-related QoL and ADL

capacity [26]. All participants received a simple, structured diary. Persons

with PD were instructed to record each physical activity (date, type, duration,

whether alone or with someone) and perceived psychological well-being

(five-point Likert scale) both before and after the activity. Near-ones were

instructed to record own QoL, ADL capacity and physical and psychological

well-being, while also understanding the challenges persons with PD face. During

the intervention, the gym-rehabilitation participants engaged in twice-weekly

group physical activity at the local gym setting with a physiotherapist present

and other personalized rehabilitation plan exercises. The home-rehabilitation

participants engaged in twice-weekly physical activity in their own homes using

the Träning på recept© training program for PD (Training with a prescription, specialized

physician- and physiotherapist-developed short physical exercise films in

Swedish, https://traningparecept.se/trana-med-parkinsons-sjukdom/) and other

personalized rehabilitation plan exercises. At the mid-point of the

intervention, new physiotherapist-participant discussions were held by

telephone, during which positive feedback and further instruction was provided.

At the end of the intervention, a last physiotherapist-participant meeting was

held, during which the participants’ clinical functional capacity was

re-measured (M2, week eight), and the participants once more completed the

PDQ-39 questionnaire and donated their diaries to the research team for further

analysis. Due

to small subsample sizes, the data were analyzed with descriptive statistical

analyses on both the group and subgroup levels. Intergroup median, standard

deviation and differences could not be measured. The missing data can be seen

in Tables 1 and 2. A

total of 25 participants participated in the PISER pilot intervention autumn

2019. Eighteen were persons with PD, of which the majority (n =12, 66%) were

male, aged 53-86 years (mean 70). Seven were near-ones (spouses), of which the

majority were female (n=6, 88%), aged 67-79 years (mean 71.5 years). Of those

invited to join the project, eight persons with PD and ten near-ones declined

to participate, which is quite usual in this age group [6]. Thus, the PISER

intervention was established to be feasible [27] in relation to recruitment of

participants with PD but not effective with regard to their near-ones. Four

subgroups were established: Persons with PD, Gym rehabilitation (PD/Gym);

Persons with PD, Home rehabilitation (PD/Home); Near-ones, Gym rehabilitation

(N-O/Gym); Near-ones, Home rehabilitation (N-O/Home). No-one in home

rehabilitation group chose to use digital devices such as VR glasses, which may

be perceived as unnecessary or inconvenient to use, but when watching the

Träning på recept© films, they used tablets or laptops. The

intervention was established to be feasible in relation to study procedures,

data collection procedures and to outcome measures [27] for all participants

followed the intervention scheme and its´ outcome measures. Participants in the

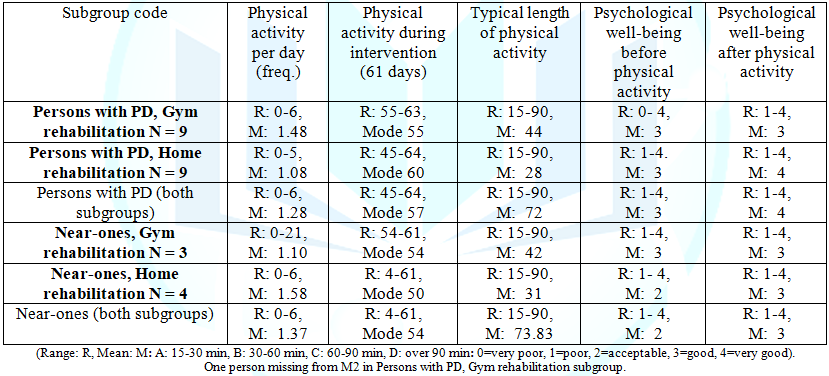

PD/Gym subgroup (n=9) engaged in physical activity 1.48 times per day (mean,

Table 1). The typical length of physical activity was about 44 minutes. As

per their choice, the participants in this subgroup engaged in twice-weekly

group physical activity at the local gym setting. Other individual exercise most

frequently undertaken was utilitarian, e.g., house chores, but even group

strength training, walking/Nordic walking to and from the gym was seen.

Participants in this subgroup exercised mostly (53%) with others in addition to

the gym rehabilitation activities in group. Their psychological well-being both

before and after physical activity was rather good (mean 3). Participants

in the PD/Home subgroup (n=9) engaged in physical activity 1.08 times per day

(mean), and the typical length of their physical activity was about 28 minutes.

As per their choice, the participants in this subgroup engaged in twice-weekly

physical activity by training according to the Träning på recept© films in own

home. Other individual exercise most frequently undertaken included walking,

rowing, stretching exercises, cross training and utilitarian exercise.

Participants in this subgroup exercised mostly alone (80%) and their

psychological well-being before physical activity was rather good (mean 3) and

after physical activity very good (mean 4). Participants

in the N-O/Gym subgroup (n=3) engaged in physical activity 1.10 times per day

(mean), about 42 minutes. The participants in this subgroup engaged in

twice-weekly group physical activity at the local gym setting. Other individual

exercise most frequently undertaken was utilitarian, but even walks, strength

training in group, stretching exercises, Nordic walking, ball sports and yoga

were seen. Near-ones in this subgroup exercised with others (52%) in addition

to the gym

rehabilitation activities. Their psychological well-being both before and

after physical activity was rather good (mean 3). Participants

in the N-O/Home subgroup (n=4) engaged in physical activity 1.58 times per day

(mean), about 31 minutes. However, one participant recorded that he/she engaged

in physical activity only four times during the entire eight-week intervention

period. The near-ones in this subgroup engaged in twice-weekly physical

activity in own home by training according to the Träning på recept© films.

Other individual exercise most frequently undertaken included walking,

utilitarian exercise, relaxation exercises, strength training in group, and

dancing. Participants in this subgroup exercised mostly alone (78%), their

psychological well-being before physical activity was rather poor (mean 2) and

after physical activity rather good (mean 3). Before

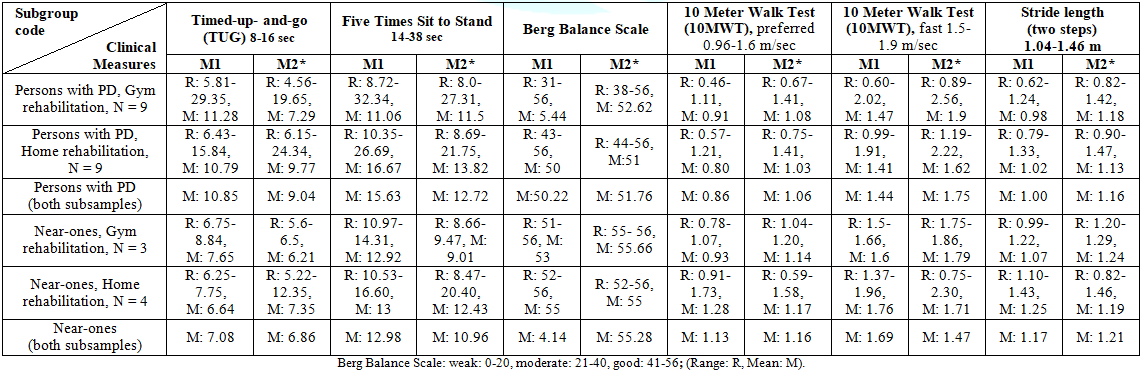

the intervention (M1), the clinical measurements for the PD subgroups were

fairly homogenous but some differences were seen (Table 2). Regarding the Five

Times Sit to Stand, the PD/Gym subgroup showed a mean of 16.67 versus the

PD/Home subgroup’s mean of 11.06, which could indicate that the PD/Home

subgroup had weaker muscles. Also, regarding the 10 meter´s walking tests

(10MWT), the PD/Home subgroup showed 0.80 versus the PD/Gym subgroup’s 0.91,

which could indicate that the PD/Home subgroup had slightly more problems

walking. When the PD subgroups were combined, we saw that before the

intervention (M1) the Timed-up-to-go, TUG (10.85), the Five Times Sit to Stand

(15.63) and step length, SL (1.00) were normal, the Berg Balance Score, BBS was

good (50.22), but the 10MWT was below normal (0.86). After the intervention

(M2), better outcomes for all clinical measurements were seen, and the 10MWT

was normal (1.06). Note that due to small sample sizes the significance tests

between groups could not be analyzed. Before

the intervention (M1), the clinical measurements for the N-O subgroups were

also fairly homogenous. The exception was the 10MWT, where the N-O/Home

subgroup showed a higher mean, 1.28 m/sec, versus the N-O/Gym subgroup’s 0.93

m/sec. After the intervention (M2), better outcomes for all clinical

measurements for both N-O subgroups were seen, but improvement was especially

seen for the N-O/Gym subgroup regarding the Five Times Sit to Stand (M1: 12.9,

M2: 9.01), 10MWT (M1: 0.93, M2: 1.14), and SL (M1: 1.07, M2: 1.27). While the

N-O/Home subgroup demonstrated slightly poorer outcomes for clinical

measurements after the intervention, the differences are marginal. Clinical

outcomes for the combined N-O subgroups before (M1) and after the intervention

(M2) were somewhat better in comparison to the combined PD subgroups, as

anticipated. Note that due to small sample sizes the significance tests between

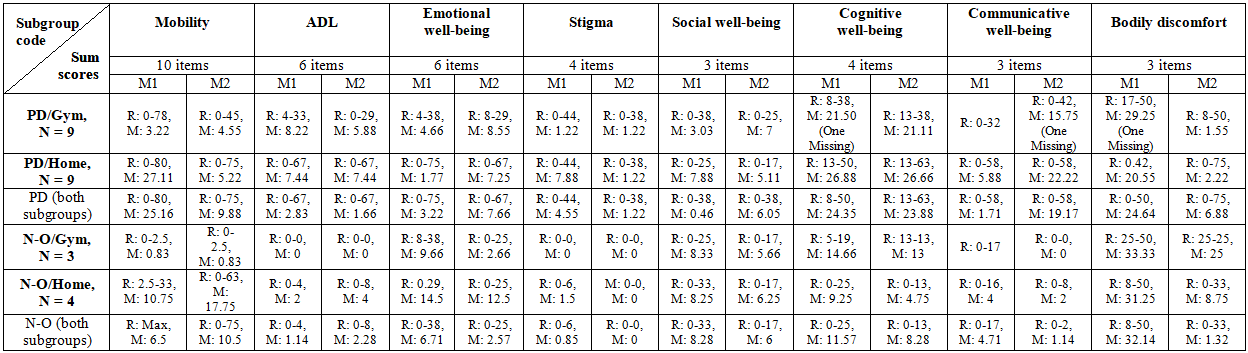

groups could not be analyzed. Table1:Physical activity and psychological well-being, per participant diaries. Table2: Clinical measurements before (M1) and after (M2) an eight-week intervention.. Table3:PDQ-39 on sum variable levels per subgroup, before and after rehabilitation. When

comparing the subgroups’ PDQ-39 scores before the intervention (M1; PD/Gym to

PD/Home, N-O/Gym to N-O/Home), mobility for both PD subgroups was seen to be

homogenous, but differences were seen regarding all other domains (Table 3).

The PD/Home subgroup more often reported problems regarding ADL (mean 27.44),

emotional well-being (21.77), stigma (17.88), social (7.88), cognitive (26.88)

and communicative well-being (25.88), indicating that they more often had

problems with ADL functions and health-related QoL. The PD/Gym subgroup more

often reported problems regarding bodily discomfort (29.25). When comparing

differences between the N-O subgroups before the intervention (M1), the

N-O/Home subgroup more often reported problems regarding mobility (10.75),

while the N-O/Gym subgroup more often reported problems regarding emotional

well-being (19.66), cognitive well-being (14.66) and bodily discomfort (33.33).

Again, due to small sample sizes the significance tests between groups could

not be analyzed. When

comparing the subgroups’ PDQ-39 scores before and after the intervention (M1 to

M2; internal, within-subgroup comparison), both improvements and reversals were

seen. For all subgroups, ADL and cognitive well-being scores were nearly the

same at M1 and M2. At M2, the PD/Gym subgroup more often reported problems

regarding bodily discomfort (31.55), but less often reported problems regarding

mobility (14.55), ADL (15.88), emotional (18.55), social (7.0) and

communicative well-being (15.75). The PD/Home subgroup reported slightly more

problems with bodily discomfort (22.22), but less often reported problems

regarding emotional well-being (17.25), stigma (11.22), social (5.11) and

communicative well-being (22.22). The N-O/Gym subgroup did not report more

problems for any domain, but instead less often reported problems regarding

emotional (12.66), social (5.66) and communicative well-being (0.00) and bodily

discomfort (25.00). The N-O/Home subgroup more often reported problems regarding

mobility (17.75) and ADL (4.00), but less often reported problems regarding

cognitive well-being (4.75) and bodily discomfort (18.75). The

aim of this paper was to describe the development of a person-centered,

interactive, systematic, effective rehabilitation intervention for persons with

Parkinson’s and their near-ones, and outcomes of a pilot study. The project was

initiated by some persons with PD and thereafter, as recommended [15,16],

developed and conducted in intense collaboration: between persons with PD,

near-ones and an inter-professional group (registered nurses, a

physiotherapist, digital/virtual healthcare system experts, academic

researchers). Public and patient involvement [23], the principles of

human-centered co-design [24] and person-centeredness [17-20] were all used to

help create a foundation for the pilot intervention. The research group decided

to focus on an active physical lifestyle, through which PD symptoms can be

alleviated and functional capacity maintained or improved [1]. Furthermore, the

psychosocial and cognitive aspects of rehabilitation were included [9], seen in

the intervention as supporting persons with PD and their near-ones in engaging

in physical activity in a group (gym-rehabilitation subgroups) or at home with

someone (home-rehabilitation subgroups) and as measuring participants’

perceived psychosocial well-being and health-related QoL [11-13] before and

after the rehabilitation intervention [14]. A

total of 25 participants participated in the pilot intervention. Of these, the

majority were persons with PD (n=18), male aged 55 or older, with early- or

mid-stage PD. This makes the sample relevant in relation to PD incidence and

prevalence internationally [c.f. 1,2, 6] and witnesses for the feasibility of

recruitment of participants with PD. Participation was voluntary and based on

participants’ intrinsic motivation [2] instead of objective PD stage [11]. In

this pilot study, participants’ own perceptions of functional capacity and

psychosocial well-being was in focus instead of number of years since

diagnosis, medication, or other illnesses. Both PD subgroups had already before

the intervention (M1) experienced limitations in ADL and health-related QoL,

which indicates that all the participants with PD were in immediate need of

rehabilitation [cf. 4,7,8]. Especially the PD/Home subgroup showed functional

limitations and poor health-related QoL at M1 when compared to the PD/Gym

subgroup: mobility (27 vs. 23), ADL (27 vs. 18), stigma (18 vs. 11), cognitive

(27 vs. 22) and communicative well-being (26 vs. 17.5). However, at M1 the

PD/Gym subgroup reported more problems with other domains than the PD/Home

subgroup: emotional (25 vs. 22) and social well-being (13 vs. 8) and bodily

discomfort (29 vs. 20.5). The PD/Gym participants might perhaps have chosen

group activity in an attempt to improve these domains. Participants in the

PD/Gym subgroup engaged in physical activity 1-5 times per day (mean 1.48), and

the typical length of physical activity was about 44 minutes. Participants in

the PD/Home subgroup (n=9) also engaged in physical activity 1-5 times per day

(mean 1.08), but the typical length of physical activity was about 28 minutes.

Psychological well-being after physical activity even differed between these

subgroups. At M2, the PD/Gym subgroup showed a mean of 3 and the PD/Home

subgroup showed a mean of 4, even though the PD/Home subgroup exercised mostly

alone (80%). It might be the physical activity itself and not the social

context that affects perceived psychological well-being [cf. 11]. After

the intervention (M2), better outcomes for all clinical measurements were seen

for both PD subgroups, and the 10MWT was normal. The PD/Gym subgroup reached

overall slightly better outcomes than the PD/Home subgroup. This may be due to

better functional capacity prior to inclusion in the study, the presence of a

physiotherapist in the gym setting, or the social aspects of group

rehabilitation. Regarding health-related QoL, both PD subgroups reported better

emotional, social and communicative well-being at M2 [cf. 12-14]. Among others,

the PD/Gym subgroup less often reported problems regarding mobility and ADL,

and the PD/Home subgroup less often reported problems regarding stigma. Still,

both PD subgroups more often reported bodily discomfort. This could be due to a

lack of awareness of own physical capacity (or limitations) prior to

intervention period or can be attributed to self-comparison with other

participants during the intervention, especially in gym-group, or incorrect

self-reporting. Seven

participants were near-ones (n=7.38%), and of these the majority were female

(88%), elderly (mean 71.5 years) spouses of persons with PD. Of those invited

to join the project, ten near-ones declined to participate. Out of respect for

their autonomy we did not document the reasons for their refusal, nor did we

document the eventual medication or illnesses of those near-ones who

participated. We merely sought the inclusion of near-ones in this intervention,

because of the person-centered perspective we employed [18-20] and the fact

that near-ones are not usually included in PD rehabilitation [9]. The inclusion

of the spouses of persons with PD is vital to safe [6] and continuous

rehabilitation [22], because they assist with reminders and act as companions

and/or assistants. Both

N/O subgroups already before the intervention (M1) experienced decreased

functional capacity and health-related QoL. For the majority of clinical

measurements participants barely managed normal reference values, with the

exception of the BBS, for which they displayed good results. They reported

problems regarding emotional, social and cognitive well-being as well as bodily

discomfort. Such results may be related to normal aging (near-ones were older

than their spouses with PD, mean 71.5 years) or to the chronic disorder that

their partners had, due to which the near-ones as unofficial family caretakers

might feel sometimes physical or emotional exhaustion. Furthermore, PD in a

family may cause some social withdrawal [7,8] affecting the social well-being.

Still, the near-ones here did not report stigma. At

M1, the N-O/Home subgroup reported significantly more problems with mobility

than the N-O/Gym subgroup (11 vs. 0.8). Participants in the N-O/Gym subgroup

engaged in physical activity 0-2 times per day (mean 1.10), and the typical

length of physical activity was about 42 minutes. Participants in the N-O/Home

subgroup engaged in physical activity 0-6 times per day (mean 1.58), and the

typical length of physical activity was about 31 minutes. Whether physical

activity had any impact on psychological well-being differed between these

subgroups; between M1 and M2, the N-O/Gym subgroup saw no change (M1: 3, M2:

3), while the N-O/Home subgroup saw slight change (M1: 2, M2: 3). Both N/O

subgroups exercised mostly alone (80% and 78%), which might be due to social

isolation or a desire to be alone. After

the intervention (M2), the N-O/Gym subgroup had better outcomes for all

clinical measurements, especially the Five Times Sit to Stand, the 10MWT and

the SL. In contrast, the N-O/Home rehabilitation group had marginally poorer

clinical outcomes at M2. This may indicate that these participants would have

benefited from individual instruction and feedback during physical activity,

i.e., a more person-centered approach [cf. 18-20]. Regarding health-related

QoL, the N-O/Gym subgroup reported better emotional, social and communicative

well-being at M2, while the N-O/Home group reported better cognitive well-being

but more often reported problems regarding mobility and ADL. This may be

related to a new awareness of own physical resources and/or limitations,

stemming from the clinical measurements and diary. Both N/O subgroups less

often reported bodily discomfort at M2 than M1, which we attribute to increased

practice and positive bodily self-awareness. This study has some limitations: the study

subsamples were small, especially for near-ones, which negatively affected the

choice of statistical analyses and interpretation of results, as well as its´

external validity. During the next research phase, the same rehabilitation

intervention will be implemented in a larger geographical area and in larger

samples (200-300 per subgroup) making advanced statistical analyses possible.

Additionally, the time at which clinical measurements are made will be

recorded, because even those with optimal medical PD management experience

varied daily function. Furthermore, more demographic data variables will be

collected, including other diagnoses, medication, and perceived motivation. The

PISER rehabilitation intervention used here was seen to be person-centered,

systematic, feasible and effective – when individual differences were

acknowledged. All participants maintained or developed their functional

capacity, psychosocial well-being and certain aspects of health-related QoL. We

saw that an eight-week rehabilitation intervention can positively impact

self-management and functional capacity, prevent inactivity and fall risks, and

delay PD-related or other onset of activity limitations through improvements in

gait (TUG, Five Times Sit to Stand, 10MWT, SL) and QoL (emotional, social,

cognitive and communicative well-being). This was especially seen regarding

group-based rehabilitation, where social well-being is promoted and when an

instructor is present to provide person-centered instructions and feed-back or

when a person him/herself engages in continuous, goal-oriented

self-rehabilitation. Also, a daily 30-minute period of physical activity

appears to improve clinical and subjective outcomes more than shorter daily

periods. While

gym-based rehabilitation appeared to be slightly more effective than at-home

rehabilitation, one should not disregard intrinsic motivation. Bio-physiological

and environmental factors, including attitudes and support from others, and

personal factors such as age, education, experiences, preferences, motivation

and co-morbidity affect functional capacity [2]. Limited mobility can lead to

poorer ADL capacity, stigma, or decreased cognitive or communicative

well-being, resulting in increased risk for social isolation and lack of

self-rehabilitation, which negatively affects functional capacity and QoL. It

is vital that healthcare professionals and clients together analyze and discuss

the meaning of physical activity and self-rehabilitation in relation to these

functional and psychosocial issues. Even

bodily discomfort was seen to be an important component that affects functional

capacity. We saw that bodily discomfort can act as a catalyst for physical

activity or can be the result of self-analysis stemming from increased physical

activity, self-comparison with others, or the keeping of a diary. Healthcare

professionals should discuss bodily discomfort with clients, and seek to

encourage clients to engage in future-oriented thought through use of, e.g., a

diary or a digital device, and should provide instruction or suggestions for

choosing from the different physical activities as needed. Lastly, to be truly

person-centered, rehabilitation should always consist of more than physical

rehabilitation activities, it should encompass psychosocial and cognitive

components as well. This

manuscript is part of a research project funded by Eschnerska foundation,

Turku/Finland; Aktiastiftelsen in Vaasa/Finland, The Finnish Nurses Association

and Svenska Österbottens samfund/Finland. The sponsors have not had any part in

study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, report writing or choice

of a publication forum.

1. Current care guidelines: Parkinson’s disease (2018). 2. Keus SHJ, Munneke M, Graziano M, Paltamaa J, Pelosin E et al. On behalf of the Guideline Development Group. European physiotherapy guideline for Parkinson’s disease (2014) KNGF/ParkinsonNet, Netherlands. 3. Rizek P, Kumar N and Mandar SJ. An update on the diagnosis and treatment of Parkinson disease (2016) CMAJ 188: 1157-165. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.151179 4. Hariz G and Forsgren I. Activities of daily living and quality of life in persons with newly diagnosed Parkinson’s disease according to subtype of disease, and in comparison to healthy controls (2011) Act Neur Sca 123: 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0404.2010.01344.x 5. Ebben J. How to make patient included innovations successful. Upgraded Life Festival, Helsinki. 6. Gisbert R and Schenkman M. Physical therapist interventions for Parkinson Disease (2015) Phys Ther 95: 299-305. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20130334 7. Balash Y, Korczyn AD, Knaani J, Migirov AA and Gurevich T. Quality-of-life perception by Parkinson’s disease patients and caregivers (2017) Act Neur Sca 136: 151-154. https://doi.org/10.1111/ane.12726 8. Kelly DH, McGinley JL, Huxham FE, Menz HB, Watts JJ, et al. Health-related quality of life and strain in caregivers of Australians with Parkinson’s disease: An observational study (2012) BMC Neur 12: 57-62. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-12-57 9. Vaartio-Rajalin H, Rauhala A and Fagerström L. Person-centered home-based rehabilitation for persons with Parkinson’s disease – a scoping review (2019) International Journal of Nursing Studies 99: 103395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103395 10. Hoehn MM and Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression, and mortality (2001) Neurology 57: 11-26. 11. Hedman M, Pöder U, Mamhidir A-G, Nilsson A, Kristifferzon M-L et al. Life memories and the ability to act: the meaning of autonomy and participation for older persons when living with chronic illness (2015) Sca J Car Sci 29: 824–833. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12215 12. Nicoletti A, Mostile G, Stocchi F, Abbruzzese G, Ceravolo R, et al. Factors influencing psychological well-being in patients with Parkinson’s disease (2017) PLOS ONE 15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189682 13. Ylikoski A, Martikainen K, Sieminski M and Partinen M. Sleeping difficulties and health-related quality of life in Parkinson’s disease (2016) Act Neur Sca 135: 459-468. https://doi.org/10.1111/ane.12620 14. Doga VB, Koksal A, Dirican A, Baybas S, Dirican A, et al. Independent effect of fatigue on health-related quality of life in patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (2015) Neur Sci 36: 2221–2226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-015-2340-9 15. Ferrazzoli D, Ortelli P, Zivi I, Cian V, Urso E, et al. Efficacy of intensive multidisciplinary rehabilitation in Parkinson’s disease: a randomised controlled study (2018) J Neurol Neurosur and Psych 89: 828-835. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2017-316437 16. Earhart GM and Williams AJ. Treadmill Training for Individuals with Parkinson Disease (2012) Phys Ther 92: 893-897. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20110471 17. Institute of Medicin. Crossing the quality chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century (2016) National Academy of Sciences. 18. Ekman I, Swedberg K, Taft C, Lindseth A, Norberg A, et al. Person-centered care-ready for prime time (2011) Eur Journal of Card Nur 10: 248-251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2011.06.008 19. McCormack B and McCance TV. Development of a framework for person-centred nursing (2006) J of Adv Nur 56: 472-479. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04042.x 20. Kitwood T. Dementia reconsidered: the person comes first (1997) Open University Press, United Kingdom. 21. Vaartio-Rajalin H and Fagerström L. Professional care at home: patient-centeredness, interprofessionality and effectivity? A scoping review (2018) Health Soc Care Comm 27: e270-e288. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12731 22. Moldovan AA and Dogaru G. Increasing functionality and the quality of life through medical rehabilitation in patients with Parkinson’s disease (2014) Balneo Res Jour 5: 193-198. https://doi.org/10.12680/balneo.2014.1077 23. INVOLVE. What is public involvement in research? (2019). 24. Kachirskaia I, Mate KS and Neuwirth E. Human-centered design and performance improvement: better together (2018). 25. Tuulaniem J. Service design (2013) Talentum Oyj. 26. Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick L, Peto V, Greenhall R and Hyman N. The PDQ-8: Development and validation of a short-form Parkinson's disease questionnaire (1997) Psy Hea 12: 805-814. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870449708406741 27. Orsmond G and Cohn ES. The distinctive features of a feasibility study: objectives and guiding questions (2015) OTJR (Thorofare N J) 35: 169-177. https://doi.org/10.1177/1539449215578649 Heli Vaartio-Rajalin, Faculty of Health

Sciences, Åbo Akademi University, Strandgatan 2, 65100 Vasa, Finland, Tel: +358

50 3427164, E-mail: hevaarti@abo.fi

or heli.vaartio-rajalin@abo.fi Heli VR, Camilla M,

John N and Lisbeth F. Developing person-centered, interactive, systematic,

effective rehabilitation (PISER) for persons with parkinson’s - The outcomes of

a pilot intervention (2020) Neurophysio and Rehab 3: 1-7. Parkinson’s disease,

Rehabilitation, Person-centeredness, Intervention, Pilot, Feasibility. Developing Person-Centered, Interactive, Systematic, Effective Rehabilitation (PISER) for Persons with Parkinson’s - The Outcomes of a Pilot Intervention

Abstract

Full-Text

Introduction

Background

Materials and

Methods

Results

Discussion

Conclusion

Acknowledgment

References

*Corresponding

author

Citation

Keywords