Research Article :

Chidi Okorie Onwuka and Ima-Obong A Ekanem Results:

The overall sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative

predictive value for VIA were 100%,80%,76.9%, and 100%, respectively compared

to 80%, 100%, 100%, and 88.2% for conventional Pap smear. Visual inspection of

the cervix with acetic acid for cervical cancer screening is not specific but

has a high negative predictive value. Cervical

cancer is the commonest malignant tumour of the female genital tract

and one of the leading causes of cancer mortality in women worldwide with a

global annual incidence of over 500,000 [1,2]. Greater than 85% of these new

cases and about 88% of these cancer related deaths occur in resource-poor countries

[2]. It is the second most common cause of cancer related deaths in regions of

the world where women do not have access to regular gynaecological care and

screening [3]. Visual inspection with

acetic acid requires minimal equipment, does not require any laboratory, can be

performed by non-physicians with adequate training, is inexpensive and yields

immediate results. The WHO has endorsed VIA for cervical cancer screening in

less developed countries with non-existent or poorly executed cervical cancer

prevention programmes since about 80% of all cervical cancer cases occur in

these countries [8]. Visual inspection with acetic acid is not without its draw

backs. Acetowhite lesions are not unique to cervical precancerous lesions. This

generates false positive cases that can lead to overtreatment which can in turn

overwhelm the treatment centres [8]. Also, it is subjective since it depends on

the clinician’s interpretation of what is seen, and is not an appropriate

screening method for postmenopausal women due to fibrosis and leucoplakia of

the cervix [8]. This study was carried

out to compare the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and

negative predictive value of visual inspection with acetic acid and Pap smear

of the cervix as cervical cancer screening methods among HIV-negative and HIV-positive

women in this region of Nigeria with high HIV prevalence. This comparative

cross-sectional study was carried out in the cytology clinic of University of

Uyo Teaching Hospital, Uyo after approval of the study protocol by the Ethical

committee of the hospital. A total of 461

ever-married or sexually active consenting women were recruited for this study

by word of mouth. Patients bleeding per vaginum, patients with previous

abnormal Pap smear result and pregnant

women were excluded. The results of 449 participants (97.4%), comprising 226 HPW and 223 HNW

were suitable for statistical analysis. Women who did not come back for a

cervical biopsy after an abnormal Pap result or a positive VIA were excluded in

the calculation for sensitivity and specificity. Table 1

shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants who were

aged between 18-60 years with a mean age of 35.24±9.26 years and 35.63±8.44

years in the control- and case- participants respectively. More than half of

the HNW were married (64.1%) and had a secondary or tertiary level of education

(75.6%). Only about one-third of the HPW were married (36.7%) but most of them

also had secondary or tertiary level of education (76.1%). Most of

the women in this study attained menarche at or below

14 years of age (72.6% of the HNW and 67.3% of the HPW) and also had their

sexual debut at or below 18 years (55.2% of the HNW and 68.1% of the HPW) but

most of the HPW (57.1%) had four and above lifetime number of sexual partners

unlike the HNW (39.2%). The study shows that majority of the participants have

a parity between 0 and 2 (57.8% of controls and 69.5% of cases). Only one-tenth

of the study participants in both groups had ever used combined oral

contraceptive pills while about one-third of them

occasionally take alcohol. Most of the study participants are non-smokers

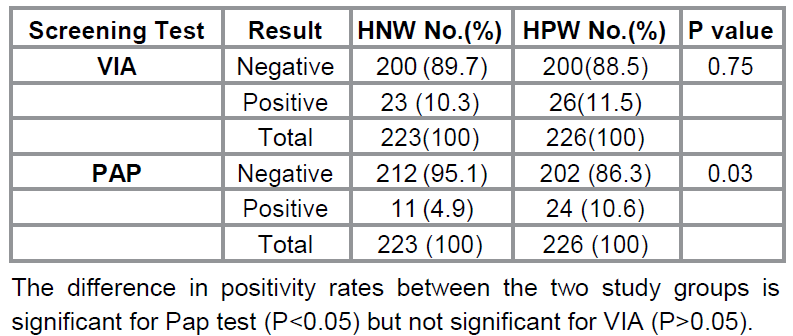

(99.6% of HNW and 99.1% of HPW). Table 2 shows

the positivity rates of VIA and Pap test. Twenty six out of the 226

case-participants (11.5%) and 23 of the 223 control-participants (10.3%) were

positive by VIA, while 10.6% of the case-participants (24 out of 226) and 4.9%

of the control-participants (11 out of 223) were detected positive by Pap test.

A positive Pap test was considered ASCUS or worse lesions. The difference in

positivity rate between the two study groups is significant for Pap test

(P<0.05) but not significant for VIA (P>0.05). Further

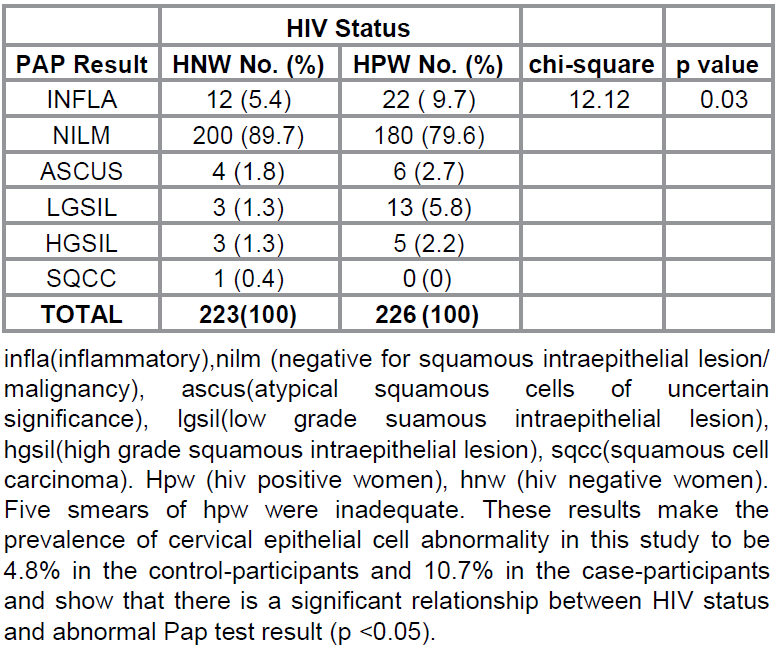

analysis shows the distribution of the Pap test results in the study population

(Table 3). Out of the 231 HPW, 22 (9.7%) had an inflammatory smear and the rest

sub-classified as NILM (180 cases, 79.6%), ASCUS (6 cases, 2.7%), LGSIL

(13cases, 5.6 %), HGSIL (5 cases, 2.2%). Five of the HPW (2.2%) had inadequate

smears due to scant cellularity and excessive mucus obscuring the squamous

epithelial cells. There was no case of cervical cancer in the

case-participants. Twelve of the HNW (5.4%) had an inflammatory smear while the

results of the rest were classified as NILM (200 cases, 89.7%), ASCUS (4 cases,

1.8%), LGSIL (3 cases, 1.3%), HGSIL (3 cases, 1.3%), and Squamous cell

carcinoma (1 case, 0.4%). These

results make the prevalence of cervical epithelial cell abnormality in this

study to be 4.8% in the control-participants and

10.7% in the case-participants and show that there is a significant

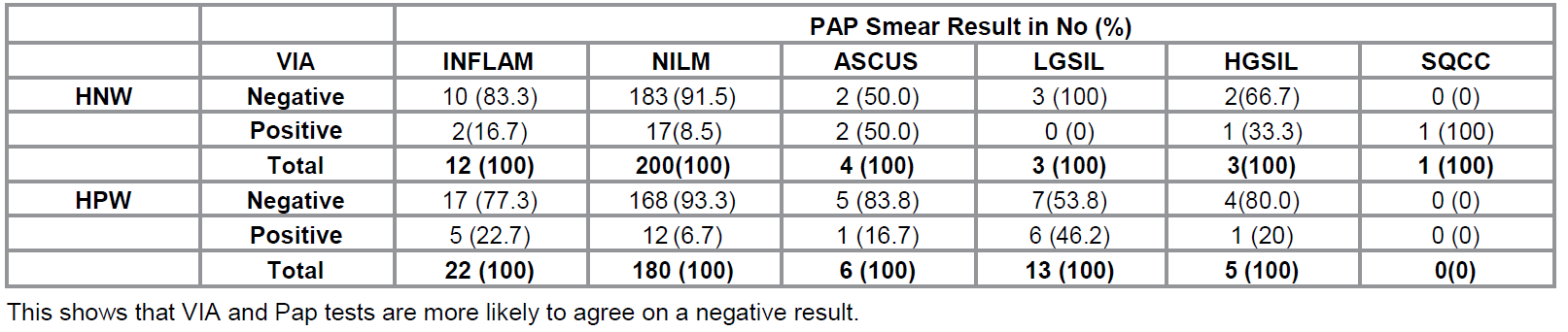

relationship between HIV status and abnormal Pap test result (p <0.05). Table 4 shows the distribution of VIA results in relation to Pap

test results. In the control group, VIA was positive in 16.7% of the

inflammatory smears and 8.5% of the NILM. Fifty per cent of the ASCUS, 100% of

the LGSIL and 66.7% of HGSIL were detected negative by VIA. The SQCC was

positive by VIA. Among the HPW, 22.7% of the inflammatory smear and 6.7% of

NILM were positive on VIA while 83.3% of ASCUS, 53.8% of LGSIL and 80% of the

HGSIL were negative on VIA. This shows that VIA and Pap tests are more likely to

agree on a negative result. All the cases that were negative on both VIA and Pap tests were

confirmed truly negative by biopsy (normal cervices, inflammatory, squamous

papilloma, endocervical polyp). All the cases that were positive on both VIA

and Pap tests were confirmed truly positive on biopsy (CIN-1, CIN-2, CIN-3, and

SCC). Two out of the 5 cases that were VIA positive but Pap negative were

confirmed positive by biopsy (1 CIN-1 and 1 CIN-2) while 3 were reported

negative (2 normal, 1 Nabothian cyst). When the HIV status and only positive screening tests were considered, 7

out of the 9 VIA positive subjects biopsied in the control group (77.8%) and 3

out of the 4 VIA positive patients biopsied in the case-participants (75%) were confirmed positive. All the

positive Pap smears biopsied in the two groups (6 control- and 2

case-participants) were confirmed positive by biopsy. This shows that Pap test

is more specific than VIA in both groups of study participants. Table 1: Socio-demographic and Clinical characteristics. Table 2:

Positivity rate of VIA and

Pap test in the study-participants. Due to the unique association between HIV and HPV in the pathogenesis of cervical cancer, regions with high HIV

prevalence also have high rates of cervical cancer since women comprise about

50% of adults living with HIV/AIDS [9,10].

Many studies have been done to compare the performance of VIA and Pap smear as

cervical cancer screening tools with a wide range of results. To the best of

our knowledge, no published data exist for such a study in this region of

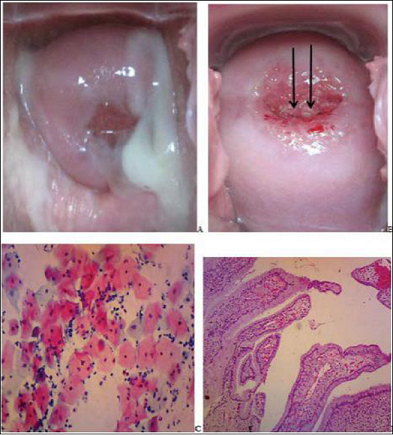

Nigeria with a high prevalence of HIV infection (Figure 1). The

socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants in this study are

similar to those noted in related studies [11-13]. This study showed that VIA was positive in 26 (11.3%) of the HPW and 23

(10.3%) of HNW while Pap smear cytology showed epithelial cell abnormality in

24 (10.7%) of the HPW and 11(4.8%) of the HNW. There was no statistically

significant relationship between HIV status and VIA positivity (p=0.75) Table 3: Distribution of Pap results according to HIV status. Table 4:

Distribution of VIA results

in relation to Pap test results and HIV status but HPW

were 2.5 times more likely to be Pap positive than HNW (p< 0.01). These discrepancies

in the positivity of VIA and Pap test when used on the same group of patients

have also been observed in several studies [14-18]. VIA tends to be more sensitive but less

specific and labels more women positive than Pap test. Reports from South African

and Zambian studies have noted a higher VIA positivity in HPW ranging from

32.6% [14] to 43.7% [15], respectively. A study in Botswana by Ramogola-Masire

et al. among 2,175 HPW showed 15.2% VIA positivity that were histologically

confirmed CIN [16]. Similar VIA studies

in Mali and Tanzania conducted on women regardless of their HIV status have

also reported varying positivity ranging from 2.6% [17] to 7.1% [18] respectively. The discrepancies noted with these VIA

studies may be attributable to a lack of reproducibility of this screening

method, differences in exclusion criteria and age differences. Also regional

variation in HIV prevalence, HPV and cervical neoplasia burden may account for the regional discrepancies observed in VIA

studies. The rate of VIA positivity

observed in this present study is however supported by studies that recorded

similar frequencies

[19,20]. The low positivity of VIA noted in this

study might be because of the low prevalence of abnormal cervical cytology in

both the cases and control groups used in this study, recording only distinct

acetowhite areas as positive and not including cervix with postmenopausal leukoplakia nor faint and suspicious whitish appearance. The problem of

inter-observer variability is also relevant [21]. Using

biopsy positive cases as gold standard, this study showed that VIA is more

sensitive but less specific than Pap test. A threshold of CIN-1 or worse lesion was considered a positive biopsy. The

sensitivity of VIA in the total study population regardless of HIV status was 100% while that for Pap test

was 80%. Combining VIA and Pap test gave a sensitivity of 100%. When the HIV

status was considered, the sensitivity of VIA and VIA+PAP was 100% in both

groups of women while that for Pap test was 85.7% in the HNW and 66.7% in the

HPW. This higher sensitivity of VIA noted in this study is supported by

findings in several studies that have yielded a wide range of results. The values

for the sensitivity of VIA reported in literature range from 60 to over 90%

while that for cytology span from 23% to 99% [22,23]. Rana et al reported sensitivities of 31.6% vs

78.2% for VIA and Pap smear respectively while Gravitt et al found 59.7% vs 57.4% in a similar study

[24,25]. The sensitivity pattern seen in

this study is similar to that observed by Akinola et al in Lagos, Nigeria [12]. Various reasons account for the

varied result in most studies comparing the sensitivity of VIA and Pap smear in

biopsy positive cases. One such factor is the threshold of positive

histopathology (Figure 2). This study used a threshold of CIN 1 or worse while other studies used CIN 2 or worse lesions.

Also, the problems with conventional Pap smear may contribute to the lower

sensitivity of Pap test observed in this and other studies. Conventional Pap

test has a lesser sensitivity in detecting precancerous lesions of the cervix

due to potential limitations which include inadequate transfer of cells to

slide, in homogeneous distribution of abnormal cells and obscuring factors such

as inflammatory

cells and blood [26]. Because

of this limitation, a potentially dysplastic

lesion can be wrongfully considered an inflammatory smear

thereby causing a lower sensitivity in comparison studies. This shows the

advantage of liquid-based cytology in Pap test. Another important factor is

inter-observer differences in reporting a positive VIA. This study reported

only cervixes or lesions on the cervix that show distinct whitening after one

minute of acetic acid application as positive. This may account for the

positivity rate of VIA obtained in this study. This buttresses the importance

of adequate training and experience in performing a VIA. Training protocol

needs to be developed in remote areas for adequate training and evaluations to

maintain the expertise of health workers involved in administering VIA. The specificities of VIA, Pap test, and VIA+Pap test in the total study

population were 80%, 100% and 100%, respectively. According to HIV status,

these values were 81.8%, 100%, and 100% in the HNW and 75%, 100, and 100% in

the HPW respectively. These findings show that Pap test is more specific than

VIA and are supported by reports from other Nigerian [11-13] and

international studies [25-27]. The commonly reported specificity for VIA ranges

from 60 to over 90% while that for conventional Pap smear spans from 7% to 97%

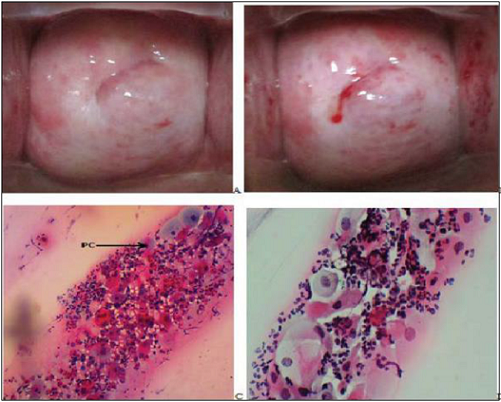

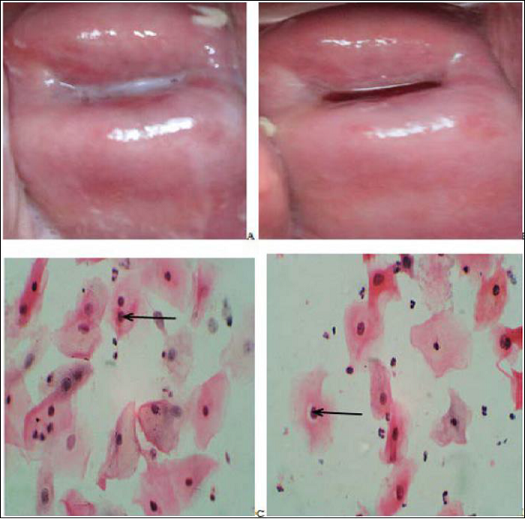

for specificity [22,23]. The reasons for the false positive cases noted in this

study included postmenopausal state, postmenopausal

cervicitis, chronic cervicitis, nabothian cysts, and squamous

papilloma. These reasons have been noted by the IARC and other studies

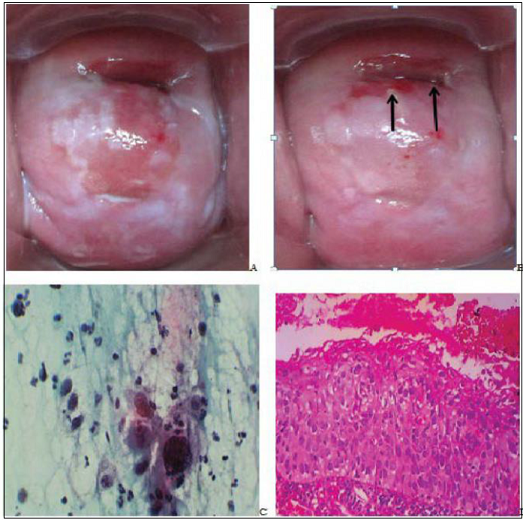

[28,29] (Figure 3). In this

present study, it was observed that combining VIA and Pap smear increased the

sensitivity of Pap test and the specificity of VIA. This is similar to the

finding by Mahmud et al in Pakistan in a study done to compare VIA and Pap

smear in cervical cancer screening [30] (Figure 4). This finding is important

and points to the fact that VIA can be utilised in two ways in resource-limited

and developing countries. First, due to its higher

sensitivity, it can be utilized in mass screening exercise to triage women who

would benefit from further evaluation by other more specific methods of

cervical cancer screening. Secondly, due to the improved sensitivity and

specificity of the combined tests, VIA can be used to complement conventional

Pap smear in opportunistic screening of women with no assurance of follow up

contact and in tertiary institutions with limited cytopathologist and absent

liquid-based Pap smear preparations. One major problem with VIA is its lack of specificity. VIA is more

sensitive but less specific than Pap smear in detecting precancerous lesions of

the cervix and if used as an alternative to Pap smear may result in increased

referral for colposcopy and biopsy which could be burdensome in some developing countries.

Also, in settings where the ‘see-and-treat approach is adopted without

confirmation using other screening modalities, VIA would lead to over

treatment. However, in resource-poor settings, due to the increased risk of HPV

infection in HIV- infected women, and the accelerated progression from cervical

neoplasia to invasive cancer in HPW, the benefits of overtreatment, increased

referral for colposcopy and biopsy far outweigh the danger of failure to

diagnose a potentially dysplastic lesion. More so, to prevent an overtreatment,

VIA can be used in a large scale programme to triage women who would benefit

from further evaluation including VILI (visual inspection with Lugol’s Iodine),

VIAM (visual inspection with acetic acid under magnification), Pap smear, colonoscopy

and directed biopsy, and HPV DNA testing. This

study also showed that VIA has a higher negative predictive value (NPV) than

Pap test. The NPV of VIA, Pap test, VIA+Pap in the total study population in

this study were 100%, 88.2%, and 100%, respectively. These values were 100%,

91.7%, and 100 in the control group, and 100%, 80%, and 100% in the

case-participants, respectively. Other studies have reported a NPV for VIA to

be close to or more than 90% which support the finding in this study [22-25]. Also,

the negative percentage agreement between VIA and Pap test was higher than the

positive percentage agreement in this study (93.1% vs 65.4%). This further

supports that VIA has a high NPV. This high NPV of VIA is of benefit in

resource-limited areas as a woman who tests negative by VIA can be reassured

and sent home without further evaluation with more costly protocol. This is

important because the vulnerable groups for cervical cancer are the poor, rural

dwellers, and HPW [31]. The

positive predictive value (PPV) for VIA, Pap test, and VIA+Pap in the total

study population in this study were 76.9%, 100%, and 100%, respectively.

Considering the HIV status, these values are 77.8%, 100%, and 100% in the HNW

and 75%, 100%, and 100% in the HPW, respectively. The reported value for PPV of

VIA in previous studies ranges from 3.8% to 90% [32]. This finding of

comparable PPV of VIA and Pap test in this study differs from that seen in most

of the work cited. This might be because in this

study, only distinct acetowhite lesions where reported as positive thereby

limiting sources of false positive cases seen in most studies. Conditions that

have been reported to cause a false positive VIA include cervical

polyp, inflammation, postmenopausal leukoplakia, and metaplasia [33, 34]. In this

study, 5 out of the 22 inflammatory smears in HPW and 2 out of 10 inflammatory

smears in the HNW were reported positive by VIA but none of the positive VIA

was diagnosed inflammatory by biopsy. In comparing VIA and biopsy, no false

positive case was due to cervicitis in this study. The results of this present study and

that of other reported studies show that VIA is comparable to cytology as a cervical

cancer screening tool and can be used in resource poor settings in both HPW and

HNW for cervical screening. Because of its affordability, simplicity

and rapidity of performance, VIA has emerged as one of the promising

alternatives to Pap smear in low-resource settings for cervical cancer

screening. VIA is cheap, easy to perform by a trained nurse and the result is

available immediately allowing the triaging of women who may require further

investigation to identify and treat cervical lesions. Triaging would help

reduce the workload on the limited number of cytotechnologists and

cytopathologists in resource-poor settings if a large scale cervical cancer screening

program is to be carried out. Furthermore, in places where cytology services

are available, VIA can be used as an adjunct to improve on the sensitivity of

conventional cervical cytology in detecting cervical neoplasia since

conventional Pap smear is noted to be associated with a high rate of false

negativity from sampling and interpretative errors [35]. The major concern about VIA is its low

specificity [high rate of false positivity] which may lead to over referral and

overtreatment but the danger of missing a potentially dysplastic lesion far

outweighs the cost of an overtreatment. Moreover overtreatment can be prevented

by confirming positive cases by other methods before commencement of treatment.

This

study shows that cervicitis has no significant effect on the result of

VIA. Only 22.7% of the inflammatory

smears in the HPW and 16.7% of the inflammatory smears in the HNW were detected

positive by VIA. Using biopsy as gold standard, none of the positive VIA was

detected as inflammatory. This finding is supported by studies that have shown

no association between a false positive VIA to specific genital tract

infections other than HPV [34]. Factors

noted to be associated with VIA positivity in this study includes age and Pap

smear positivity. It was also noted that postmenopausal women are more likely

to present with a false positive VIA. In the age distribution of VIA result,

older women are more likely to present with a positive VIA (p<0.05). This

finding is similar to that seen in IARC studies [28]. The IARC recommends that

VIA should not be used in postmenopausal women for cervical cancer screening

[28]. VIA is

more sensitive but less specific than conventional Pap test. This finding is

similar to that reported in the literature. VIA could be used as an alternative

to cytology in resource poor settings in both HPW and HNW for primary cervical

screening. Due to its sensitivity, affordability, simplicity, and rapidity of

performance, VIA can be used for mass cervical

cancer screening. This would help triage women for further evaluation before

applying the appropriate treatment. This study therefore does not support the

‘see-and treat’ approach in cervical cancer management because VIA is not

specific. Also, the ‘see-and-treat’ approach will prevent generation of data to

know what is being treated and the depth of the lesion that is being treated

may not be reached, giving a false sense of safety. The

authors are grateful to the management of University of Uyo Teaching Hospital

for approving this study and to the personnel of the HIV clinic who contributed

to the success of this study. We are grateful to Mr Jezreel Ajayi for technical

assistance and for performing statistical analysis. 1.

Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, et al. Estimates of

Worldwide burden of cancer in 2008, GLOBOCAN 2008 (2011) Int J Cancer 127: 2893-2917. 2.

Ferlay J, Soerjomataran I, Ervikm M, Dikshit R, Eser R, et al. GLOBOCAN

2012 v1.0, Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: IARC Cancer Base No.11 (2013)

International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France. 3.

Ntekim A. Cervical cancer in sub-Sahara Africa. (2012) In: Topics on

cervical cancer with an advocacy for prevention, Rajamanickan R (edtr) In-Tech

Pp: 51-74. 4.

Abd El All HS, Refaat A, Dandash K. Prevalence of Cervical neoplastic

lesions in Egypt: National Cervical Cancer Screening Project (2007) Infectious

agents and cancer 2:12. 5.

Denny L, Adewole I, Anorlu R, Dreyer G, Moodley M, et al. Human

papillomavirus prevalence and type distribution in invasive cervical cancer in

Sub-Saharan Africa (2014) Int J Cancer 134:1389-1398. 6.

Del Mistro A, Salamanca HF, Trevisan H, Bertorelle R, Parenti A, et al.

Human papillomavirus typing of invasive cervical cancers in Italy (2006)

Infectious Agents and Cancer 1: 9. 7.

Castellsague X, Munoz N. Cofactors in HPV carcinogenesis of parity, oral

contraceptive and tobacco smoking (2003) J Natl Cancer Inst Monogra Pp: 20-28. 8.

Alliance for cervical cancer prevention (2004) Planning and implementing

cervical cancer prevention and control programs. A manual for managers. Seattle,

ACCP. 9.

Anderson J, Lu E, Sanghvi H, Kibwana S, Lu A. Cervical Cancer Screening

and Prevention for HIV-infected women in developing world (2014) In: Cancer

prevention from mechanism to translational benefits, Georgakilas AG (edtr). 10.

National Centre for HIV/AIDS (2009) Dermatology and STD annual report. 11.

Albert SO, Oguntayo OA, Samaila MOA. Comparative study of visual

inspection of the cervix using acetic acid (VIA) and Papanicolaou (Pap) smears

for cervical cancer screening (2012) ecancer 6:262. 12.

Akinola OI, Fabamwo AO, Oshodi YA, Banjo AA, Odusanya O, et al. Efficacy

of visual inspection of the cervix using acetic acid in cervical cancer

screening: a comparison with cervical cytology (2007) J Obstet Gynaecol 27: 703-705. 13.

Akinwuntan AL, Adesina OA, Okolo CA, Oluwasola OA, Oladokun A, et al.

Correlation of cervical cytology and visual inspection with acetic acid in

HIV-positive women (2008) J Obstet Gynaecol 28: 638-641. 14.

Kuhn L, Wang C, Tsai WY, Wright TC, Denny L. Efficacy of human

papillomavirus-based screen-and-treat for cervical cancer prevention among

HIV-infected women (2010) AIDS 24: 2553-2561. 15.

Pfaender KS, Mwanahamuntu MH, Sahasrabuddhe W, Mudenda V, Stringer JS, et

al. Management of cryotherapy-ineligible women in a “screen-and-treat” cervical

cancer prevention program targeting HIV-infected women in Zambia: Lessons from

the field (2008) Gynecol Oncol, 110: 402-407. 16.

Ramogola-Masire D, de Klerk R, Monare B, Ratshaa B, Friedman HM, et al.

Cervical cancer prevention in HIV-infected women using the “see-and-treat”

approach in Botswana (2012) J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 59: 308-313. 17.

Teguete I, Muwonge R, Traore CB, Dolo A, Bayo S. Can visual cervical

screening be sustained in routine health services? Experience from Mali, Africa

(2012) BJOG 119: 220-226. 18.

Ngoma T, Muwonge R, Mwaiselage J, Kawegere J, Bukori P, et al. Evaluation of

cervical visual inspection screening in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania (2010) Int J

Gynaecol Obstet 109: 100-104. 19.

Hedge D, Shetty H, Shetty PK, Rai S, Manjeera L, et al. Diagnostic value

of VIA comparing with conventional Pap smear in the Detection of colposcopic biopsy

proved CIN (2011) NJOG Pp: 7-12. 20.

Horo A, Jaquet A, Ekouevi DK, Troure B, Coffie B, et al. Cervical cancer

screening in Cote d’Ivoire: operational and clinical aspects according to HIV

status (2012) BMC Public Health 12:237. 21.

Sherigar B, Dalal A, Durdi G, Pujar Y, Dhumale H. Cervical cancer

screening by VIA- Interobserver variability between Nurse and Physician (2010)

Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev 11: 619-622. 22.

Rodriguez-Reyes ER, Cerda-Flores RM, Quinonez-Perez JM,

Velasco-Rodriguez V, Cortes-Gutierrez EI. Acetic acid test: A promising

screening test for early detection of cervical cancer (2002) Anal Quant Cytol

Histol 24: 134-136. 23.

Sankaranarayanan R, Rajkumar R, Theresa R, Esmy PO, Mahe C, et al:

Initial results from a randomized trial of cervical visual screening in rural

south India (2004) Int J Cancer 109: 461-467. 24.

Rana T, Zia A, Sher S, Tariq S, Asghar F. Comparative evaluation of Pap

smear and Visual inspection of acetic acid in acid (VIA) in Cervical Cancer

Screening Program in Lady Willingdon

Hospital , Lahore (2010) Annals of King Edward Medical University 16: 104-107. 25.

Gravitt PE, Paul P, Katki HA, Vendantham H, Ramakrishna G, et al.

Effectiveness of VIA, Pap, and HPV DNA testing in a cervical cancer screening

program in a peri-urban community in Andhra Pradesh, India (2010) PLoS One

5:e13711. 26.

Arbyn M, Sankaranarayanan R, Muwonge R, Keita N, Dolo A, et al. Pooled

analysis of the accuracy of Five cervical cancer screening tests assessed in

eleven studies in Africa and India (2008) Int J Cancer 123: 153-160. 27.

Duraisamy K, Jaganathan KS, Bose JC. Methods of detecting cervical

cancer (2011) Advances in Biological Research 5: 226-232. 28.

IARC Screening Group. Anatomical and Pathophysiological basis of Visual

Inspection with acetic acid (VIA) and with Lugol’s Iodine (VILI). 29.

Goel A, Gandhi G, Batra S, Bhambhari S, Zutshi V,. Visual inspection of

the cervix with acetic acid for cervical intraepithelial lesions (2005) Int J

Gynaecol Obstet 88: 25-30. 30.

Mahmud G, Tasmin N, Iqbal S. Comparison of Visual Inspection with acetic

acid and Pap smear in cervical cancer screening at a tertiary care hospital

(2013) JPMA 63: 10-13. 31.

WHO (2010) Cervical cancer summary reports. 32.

Hasanzadeh M, Esmaeih H, Tabaee S, Samadi F. Evaluation of visual

inspection with acetic acid as a feasible screening test for cervical neoplasia

(2011) J Obstet Gynaecol Res 37:1802-1806. 33.

Cagle AJ, Hu SY, Sellors JW. Use of an expanded gold standard to

estimate the accuracy of colposcopy and visual inspection with acetic acid

(2010) Int J Cancer 126: 156-161. 34.

Davis-Dao CA, Cremer M, Felix J, Cortessis VK. Effect of cervicitis on visual inspection

with acetic acid (2008) J Low Genit Tract Dis 12: 282-286. 35.

Koss LG. Cervical (Pap) smear (1993) Cancer 71: 1406-1412. *Corresponding author:

Chidi Okorie Onwuka,

Department of Pathology, University of Uyo

Teaching Hospital, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State,

Nigeria, Tel: +234 (0) 8035473424,

E-mail: dronwuka@yahoo.com

Cervical cancer, Pap smear, VIA, CytologyThe Utility of Visual Inspection with Acetic Acid in Cervical Cancer Screening

Abstract

Methodology:

Between March, 2013 and March, 2014, 461 consenting women, comprising 231 HIV

positive women (HPW) and 230 HIV negative women (HNW) were recruited and

screened for cervical cancer using conventional Pap smear and VIA

simultaneously in University of Uyo Teaching Hospital. The Pap smear findings

were classified using the 2001 Bethesda system. Patients with a positive Pap

smear or abnormal VIA findings were recalled for biopsy. The results of the two

tests were compared using biopsy as the gold standard.

Conclusion: This study does not

support a “see-and-treat” approach in cervical cancer management using VIA only.

In resource-challenged areas, VIA can be applied on a large scale basis in

primary screening for cervical cancer so as to triage, women who will benefit

from further evaluation before applying the appropriate treatment. Full-Text

Introduction

Most cases of cervical

cancer are Human

papilloma virus (HPV) associated [4-6]. Early onset of

sexual activity, early age at first pregnancy, high parity and multiple sexual

partners are associated with the risk of HPV infection [7]. Other risk factors

include presence of other sexually transmitted diseases, low socioeconomic

class, cigarette smoking and immunosuppression from any cause, vitamin

deficiency, and long term oral contraceptive use [7].

Unlike most cancers,

invasive cervical cancer is potentially preventable because it is preceded by

long precancerous stages which are most often detected by cervical smear. In

developed countries, routine and organized cytology-based screening programmes

with adequate treatment of precancerous lesions have dramatically reduced the

incidence and mortality of cervical cancer. These require a reliable health

care infrastructure, political support, adequate number of trained personnel,

and multiple clinic visits. All of these factors make the implementation of

such programmes difficult in low-resource countries where other health needs

are competing for the available resources. This makes the development of

alternative methods for cervical cancer screening necessary in such

resource-poor settings. Visual inspection of the cervix with acetic acid (VIA)

is one of such alternatives and requires the application of 3% to 5% acetic

acid to the cervix which is then examined after one minute for the

characteristic acetowhite lesions suggestive of cervical neoplasia.Materials and Methods

The study

participants were educated about cervical cancer, the screening methods,

objective of the study, and the possibility of an abnormal result. Those who

were willing to take part in the study signed a written informed consent.

A questionnaire

was administered to obtain information on each participant’s socio-demographic

factors and relevant risk factors. Participants’ confidentiality was ensured.

The procedure was explained to each of the participants. The Pap smear was

taken while observing standard protocol and promptly immersed in 95% ethyl

alcohol fixative contained in a coplin jar. With the vaginal speculum still in

place after collecting the sample for Pap smear, a cotton swab soaked in 5%

freshly prepared acetic acid was applied to the cervix. The cervix was examined

after one minute for the characteristic aceto-white appearance typical of

cervical neoplasia by unaided naked eye examination. Photographs of the cervix

were taken before and one minute after applying the acetic acid using a Canon

Power shot A80 5X optical zoom 16.0 mega pixels camera. Findings on VIA were

recorded immediately and classified based on the criteria from International

Agency for Research in Cancer into Negative or Positive. Lesions that were

positive or suspicious on VIA were biopsied in women who gave consent for the

procedure.

The

alcohol-fixed smeared slides were then stained with Pap stain using standard protocol

at the histopathology laboratory of the hospital. The 2001 Bethesda System

(TBS) of reporting cervical and vaginal cytology was used as the basis for

cytology classification.

Women who had an

abnormal cytology with a normal VIA finding were recalled for biopsy.

The biopsy materials were processed by the formalin fixed paraffin embedded

method using standard protocols. The cervical biopsies were classified according

to the WHO classification of cervical tumors.

The results of the two screening tests for each patient were compared

using the biopsy result as the reference standard. For this, all Pap smears

with the diagnosis of ASCUS or worse lesion were considered positive while all

abnormal VIA findings were considered positive. The threshold of positive

biopsy is CIN-1 and worse lesions

The

data collated were analyzed using statistical package for social sciences

version 20 (SPSS 20) and the results presented as tables. The level of

significance was set at P less or equal to 0.05. The findings of this study

were compared with those of previous studies.Results

Discussion

Conclusion

Acknowledgement

References

Citation: Onwuka CO, Ekanem IA (2017) The

Utility of Visual Inspection with Acetic Acid in

Cervical Cancer Screening. ECOA 103: 7-14 Keywords