Research Article :

Lufei Young, Susan Barnason, Van Do

Heart failure is among

the most prevalent chronic condition in older adults [1] and hospitalizations

account for the majority of costs related to treatment of heart failure [2].

Self-management is the primary key to control symptoms, disease progression and

improve health outcomes. Studies have reported the low self-management

adherence to heart failure treatment guidelines and its health consequences.

Persistently high mortality and readmission rates in rural heart failure

patients indicate a need for developing interventions to improve

self-management adherence. Effective approaches to support heart failure

patients in managing this complex, chronic condition in rural communities have

not been reported [3]. To fill the gap of knowledge and evidence regarding

interventions intended to improve self-management adherence in rural heart

failure patients, a two-group, Randomized Control Trial (RCT) was conducted to

examine the feasibility and impact of a two-phase, 12-week intervention on

patient knowledge and confidence in managing their heart failure a rural

community. It was hypothesized that enhanced patient knowledge and confidence

would improve activation levels, leading to improved heart failure

self-management adherence. The intervention combined inpatient discharge

planning with home-based self- management coaching. To evaluate the

effectiveness of the intervention on self- management adherence, the on-going

assessments were conducted at baseline (before the onset of intervention), 3-

and 6-months after the intervention. Both objective (assessed by Actigraph

monitor) and subjective data (assessed by questionnaires) were collected at

each time point. The conduct of behavioral RCT in

rural comminutes can be challenging, particularly regarding to patient recruitment

and retention. It is not uncommon for investigators to be unable to meet recruitment

goals within the proposed timeframe [4,5].To detect the statistical significant

differences between intervention and control groups, adequate sample size of

rural residents are needed [6]. Therefore, low enrollment and high attrition

rates would hinder the development of effective strategies to improved self- management

adherence in rural heart failure patients. Moreover, inadequate sample size

would limit the validity and generalizability of study results to heart failure

population residing in other rural and remote areas. To date, limited studies

[7,8] reported barriers and strategies to improve recruitment and retention of

rural participants in research studies. The purpose of this paper is to descript

the experience and lessons we learned when conducting a RCT in the rural community:

the barriers and strategies related to recruitment and retention of rural heart

failure patients in a behavioral intervention study to improve activation level

and self- management adherence. The study was approved by the University of

Nebraska Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB) and hospital ethical

committees, receiving the number of IRB PROTOCOL # 228-13-EP. All patients gave

written informed consent for participation in the study. The study was

registered at https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01964053. Research Design This is a retrospective and

descriptive design. Enrollment and recruitment started

in October 2013. Heart failure patients admitted to a rural community hospital

in Southeastern Nebraska were first screened for eligibility based on the

inclusion/exclusion criteria, then the eligible patients were approached and

asked whether they were interested in participating in the program. The author

was the nursing

staff at the community hospital and had full access to the targeted population.

The author was responsible for the recruitment and enrollment of the study

subjects. She visited the hospital on a regular daily basis, reviewed the

patients records, checked the floor daily census, and interviewed the hospital

staff (e.g., nursing staff, medical providers, housekeeping, unit secretaries,

house supervisors) to identify potential study subjects. The author

administrated two screen tools to the patients who met the inclusion criteria.

The two screen tools were used to detect the impaired cognition level and

depression. Following the screenings, the author approached each the patient

who passed the screenings and met the inclusion criteria. She asked if the

patient was interested in participating the study. The author made field notes

detailing the reasons that patients declined to participate the study. After explaining to the patients and

their family members the purpose, outcomes, procedure, and the risks and

benefits of the program, the author addressed any questions or concerns about the

consent and the study. The patients were provided ample time to review the

consent form and the study protocol prior to signing the consent. The author

also kept records on the rationale for deciding to exclude patients who passed

the initial screenings and met the inclusion criteria at

the final stage of enrollment. Following the informed consent, the enrolled

patients were randomized to either the intervention or control group. Baseline data

were collected and the patients in the intervention group received Phase I of

the intervention during their hospital stay. Within a week of discharge,

reminder calls were made by the research assistant to reinforce the purpose, risks and benefits of

the study, address any questions and concerns raised by the patients, and

remind the patients to wear the Actigraph monitors (physical activity

assessment tool) based on the study protocol. Prior to the 3- and 6-month data

collection, the participants from both groups received reminder letters about

the upcoming phone interviews from the research assistant, blood and urine

collections and Actigraph monitoring. The research assistant made additional phone

calls to remind the patients who failed to return the blood and urine samples and

Actigraph monitors. Thank you letters were sent to those who completed the data

collections. An incentive of $50 was sent to those who completed all three data

collections. The author kept records during the

recruitment, enrollment and follow-up process including the demographic data of

each patient reviewed for the study (e.g., age, gender, marital, working status),

eligibility for the study (met or not met the inclusion criteria), screening

results (passed or failed the two screening tools), consent status

(agree/decline to consent to be the participant), reasons for declining,

reasons for excluding following the initial screening, dropout time and the

reasons for dropout. Both quantitative and qualitative methods were used to describe

patients who chose to enroll or ot enroll the study. This mixed method

analysis helped us to capture a broad range of challenges and opportunities in

conducting rural

research. For the quantitative approach, the descriptive statistics (counts,

mean, standard deviation, median, percentage) were used to describe the

normally distributed continuous variables. The median and range were used to

describe non-normally distributed continuous data. Frequency and percentage

were used to describe categorical variables. A t-test for two independent

samples was used to compare the normally distributed continuous variables

between the enrollers and non-enrollers. The Mann Whitney U Test was used to

compare the variables whose normality cannot be assumed. The information

related to the barriers and effective strategies to recruit and retain the

participants were collected from the authors field notes, the written reports

from the research assistants. The qualitative data were grouped into several

categories to organize the information and develop solutions. The quantitative

and qualitative data were collected and analyzed independently and then the

findings were merged to help develop interpretation of the results. Since October 14, 2013, A total of 589

potential candidates were screened, the reasons for screen failure include: 1)

failed inclusion/exclusion criteria; 2) declined to participate; 3) transferred

to another facility; 4) deteriorating health condition; and

5) time restrictions. Among 85 subjects, one dropped out after consent, one dropped

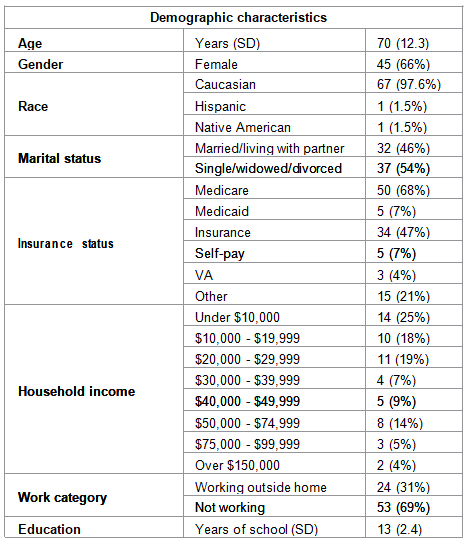

out at baseline and one subject expired. Table 1 listed subjects demographic

characteristics. The mean age is 70 ± 12.3 years. There are more women (66%)

than men (34%) in this study. The majority are white (97.6%) and not working

(69%). Sixty-two percent of subjects had annual household income below $30,000

( Table 1 ). Table1: Demographic characteristics Comparing the enrollers to non-enrollers, the enrollers were older,

female, had lower co-morbidity level, higher physical functioning, higher

patient activation level, a more positive attitude and outlook, higher health literacy,

and better self-management knowledge, skills and adherence. The non-enrollers were

often male, had more complex chronic conditions with poor prognosis, were weaker

due to progressive physical and psychological deconditioning,

and were receiving multiple treatments for multiple comorbidities. Barriers and

challenges to participating research Reasons for the decline of participation

are listed in Figure 1. Research related barriers to participating in research Inability

to perceive the study benefits: Inability to perceive the study benefits was

one of the most frequently cited reasons for not participating. Many patients refused

to participate because they did not perceive the benefit or need to be in the study.

A patient expressed, “I know....I know....you try to get me do this study so I can

be the guinea pig for others.....Nope, I need get something out of this too, not

just sacrifice....” Many other patients shared similar feelings and thoughts. Some

patients request the personal assistance with their activities of routine daily

living (e.g., bathing, cooking, shopping, and refilling the pill box). Others preferred

the intervention delivered through face-to-face format with more hands-on coaching.

One patient said, for

example: “I know all the things I need to do to keep me out of trouble, but I dont

know how. I need someone to come to my house to show me how to cook meals to keep

under 1500mg sodium a day, how to cut down the fluids.” Similarly, another patient did not think this intervention

would provide the on-going support he needed to consistently engage in the

self-management behaviors. He said, “I knew why I am [in the hospital] again, I

was not taking the pill I was supposed to and eating a lot of salty food, I know

everything you are going to lecture to me, my problem is...I am not doing what I

am supposed to do....I can be good for a week, then fall off wagon....I dont

think your program can help me ....I dont need a lecture anymore...I need

someone come to my house, physically check on me all the time.” However, others felt they were getting adequate

care from their current providers and support system, and therefore did not perceive

the need for additional support. During the intervention sessions, some

participants questioned the benefits of following heart failure

self-management guidelines. One said, “Sure, [the interventionist] told me to keep

the scheduled follow-up appointment, yes, I went to the scheduled doctor

appointment. I live on the ranch, it took me one hour to get to town and one

hour to get back home, then I waited in the waiting room for almost an hour,

then another 30 minutes in the exam room, guess what?! He spent no more than 5

minutes with me, he did not even know I was in hospital because he did not get

the letter from the hospital. You are telling me that was a helpful appointment

to me?!” Some participants voiced their doubts about the unrealistic

expectations of the self-management guidelines for heart failure patients. One

remarked, “You ask me to eat only one and one half teaspoons of salt a day, everything

has salt in it, even vegetables, I have to be a vegan to meet your requirement.

Those pills I take make me thirsty and tired all the time, how would you expect

me not to drink when the doctor prescribed the pill making me thirsty? How

would you expect me to exercise 30 minutes a day when the pill makes me tired

all the time?” Some participants dropped out because they were unable to meet

the self-management guidelines and disbelieved the benefits of self-management

guidelines. Research Related Factors • Inability to perceive the study

benefits Figure 1: Reasons to Refuse

Participating in the Research Study burden and interruption to

life were another reason for declining that was repeatedly brought up by the

patients. Many patients were discouraged by wearing the activity monitor at

least 8 hours per day for 7 days. Some felt that the weekly calls from the

interventionist were burdensome and disrupted their routines. Some patients

expressed that it was “ too much work for driving into the town for blood work ”.

Several patients were not aware of the rationale behind longitudinal studies.

They expressed disappointment about the 6-month follow up data collection and felt

“being watched for 6 months” was lengthy and burdensome. Lack

of understanding or misunderstanding the research Many research participation due to a lack of understanding

and misunderstood the research with respect to its purpose, process, procedures

and outcomes. One patient said, “ My daughter did not want me join your

program. She said your study does nothing but the experiments on me .” Another patient said, “I just

dont get it [the research project] what you are trying to do.....give me money to

take care of me??!!....Are you crazy?!” Some felt intimidated by signing the

consent. Another patient commented , “Why do I have to sign this 9-page long

paper? Are you going to take away my house if I am not doing this right?” A

patient refused to participate after we requested her social security number

for the incentive check. Ignorance and lack of understanding about the benefits of research affected

patients participation rate. Some patients refused to participate

in the study because they considered the researchers as “ outsiders ” to the community

or “ people working for the government ”. One patient asked if the study was “another

gimmick the government comes up to get people”. Some patients expressed

difficulty in trusting someone they did not know. One commented, “ What do you

know about me and my problem? You have to understand it is very hard for me to

join your program if we have never met before .” Many patients voiced their “ die

hard loyalty ” to their primary providers; thought participating the program

would jeopardize their relationship with the physicians. One

remarked, “I have been going to my family doc for years, he knows my problems

well, I dont want to upset him by going to someone else.” Many patients,

especially older ones, asked if their family doctors were aware of the study

and refused to participate the study without the “ ok letter ” from their

family doctors. Most potential candidates had

multiple chronic

conditions. They refused to participate in the study because they felt overwhelmed

and exhausted from managing their multiple health problems. One patient said, “My

health problems are taking my life away, sucking my energy dry, I am too tired

to do anything, honey.” Another patient was “ burned out ” by managing his

chronic conditions: “I have 12 doctors taking care of my health problems, I go to

doctors offices and hospitals every 2-3 weeks, sometimes, every week, I am

tired to being old, I am tired of being sick all the time, to be honest with

you, I am tired of seeing your guys, sorry.” During intervention sessions, some

participants wished to receive integrated self-management information that

would help them manage multiple chronic conditions rather than heart failure only.

For example, one participant was confused by the conflicting care instructions

for different diseases she had, explaining, “My rheumatologist told me to drink

a lot of water because he put me on this new pill causing the kidney stone, but

my heart doctor and you told me to drink less because my heart is failing. You

guys are teaching conflicting things. What am I supposed to do?” Another

participant had multiple chronic conditions, heart failure, diabetes,

osteoarthritis, and he had difficulty meeting heart failure self-management

guidelines due to the interference from his other conditions. He expressed his frustration

to the interventionist: “It was difficult for me to exercise 30 minutes a day,

I even tried to break it down to small sessions like 10 minutes in the morning,

10 minutes in the afternoon, and 10 minutes at night. I did for 2 days in a

row, then my arthritis all flared up. I have the lower spine stenosis and my

back was killing me after the walking the other day, not to mention the

blisters on the bottom of my feet... I have had diabetes for years and my feet

dont have much sensation.” Several patients conditions progressively

deteriorated during the hospital stay and they became dependent in activities

of daily living due to the complex comorbidities. As a result, the author

excluded these patients

from the study although they met the inclusion criteria and passed the initial

screening. The author did not think this self-management program would be a

good fit for those who were incapable of caring for themselves. Several patients expressed feelings

of guilt and shame regarding their current health conditions. One said, “I was

not willing to change my life when I had chance....now it is too late.” Some

participants admitted that participating in the study made them feel depressed and

angry towards themselves: “Doing this study makes me realize how bad a shape I

am in, how terrible a life I have lived, I am on 30+ pills a day, see doctors

every month, and it takes me 3 rests to get to the mailbox. Damages done when I

was young and I dont see the future”. Several patients who passed the cognition screening

tools had difficulty in comprehending the information related to heart failure self-management

knowledge. Some patients lacked understanding about the chronic nature of heart

failure. One heart failure patient said, “I dont have heart failure anymore and

I was cured by a cardiologist a couple years ago.” Another patient was

diagnosed with congestive

heart failure three years ago following her coronary artery bypass surgery.

He was surprised to know he has had this condition, stating, “Heart failure? I

dont have [heart failure], no one told me before.” Reluctance to engage in

self-management behaviors Some patients refused to participate

in the study because they were unwilling to engage in self-management

behaviors. Some had no motivation or desire to take responsibility in managing

their condition. One said, “My family doctor and the specialists take care of me

if I am sick. They know more than I do, let them worry about [heart failure].” Another

remarked , “It is not my job to manage my heart problems. I paid doctors to

take care of me”. Rural patients living on farms and

ranches were reluctant to travel long distances for lab testing. Some elderly patient with degenerative

joint diseases and arthritis expressed difficulty in walking from the parking

lot to the hospital building. A patient said, “that damn parking lot is 2 miles

away from the building, too much walking; I am not coming for the blood work.” Some

lost their ability to drive and did not want to spend money for transportation for

the lab work. Several candidates were “snowbirds” who moved to the warmer

southern states in winter months. Lack

of resources and support Rural patients living in poverty

were likely to refuse to participate in the study because of a lack of funds to

pay for transportation and telephone services. Two patients were homeless and

were discharged and transported to the homeless shelter by the police. Several

patients did not join the program because of a lack of family support and

approval. A patient told the author, “honey, Id love to join the program, but

my daughter said no.” Later on, the patient was moved to an assistant living

facility from her home following the disclosure of domestic abuse. Some potential candidates were still

working on farms, working outside of the home, traveling frequently, engaging

in busy social lives, or acting as caretakers of family members. They declined

the study because of multiple competing life demands. Strategies to Recruitment and

Retention Strategies to improve recruitment

and retention to the study are listed in Figure 2 . Relationship with the recruiter Having a recruiter who had an

established relationship with the participants and lived in the same community

seemed to foster recruitment and retention. The author, who worked as a staff

nurse at the study site, was primarily responsible for recruitment and retention.

The patients felt more comfortable and relaxed when they found out the lead of

the program was a nurse they had known for years. One patient said to the

author, “I am doing this just for YOU.” Some patients expressed their trust in

the research team member from the local community. One patients said, “I trust

you, my family trusts you, and so I will join the program for you”. Another said,

“Six months?! Well, I guess I can put up with you for six months.” Some had

previous relationships with the recruiter, saying “My wife said I should sign up for this

program, you were her nurse years ago, she said you were really good to her” When

the author explained the risks and benefits of the study, one patient said, “Yeh,

yeh, there is no such thing as risk-free, I just dont believe you would do

anything to hurt me, I know where you live, lets just cut to the chase and sign

me up!” The patients who received

encouragement from their PCPs were more likely to participate in the study. One

patient said, “My family doc said you are doing a study to help people, I will

do whatever he says.” Another patient said, “If my doctor says yes, I would do

it.” One participant admitted wanting to drop out of the study, but he stayed

to the end and completed the study. He disclosed, “If it was up to me, I would

have dropped out from this [study] a long time ago. But my family doc said this

is good for me and keeps me on the right track.” Another patient who was not

hospitalized called the author to ask join the study and was disappointed when

the inclusion criteria were explained, claiming, “My family doctor showed me

your study advertisement; he gave me your phone number to see if you can sign

me up. You dont accept anyone if it is not hospitalized?! That aint right, you

should accept anyone who has heart failure.” Patients who had previous experience

in taking part in research studies were more likely to accept the invitation.

One patient said, “I did the breast cancer research several years ago, I know

how this works, yes, sign me in.” After she completed the study, she phoned the

author and asked to be on the call list for upcoming studies. Desire for research incentives and free lab testing Many patients, especially those with low or no incomes, appreciated

the incentives provided at the completion of the study. For some participants,

the $50 incentives were significant contributions to their budget for daily

living. One participant said, “ I need the money, it will help pay for my next

week of groceries.” Some patients were interested in the free lab testing and the

other monitoring provided by the study, explaining, “I can only afford free-healthcare,

if it is free, I am in.” Some patients who were hospitalized

due to their exacerbated cardiac condition felt it was time to make changes and

focus more on their health.

They thought the self-management program would give them a jump start. A farmer

said, “I have a lot of health issues, forced me out of farming which I care most

and know best (tears coming out his eyes)......I am motivated to change my life

so I can farm again.” Some considered the hospitalization to be a wake-up call.

One patient said, “My son has not been married, I cannot go now, I need to see

him getting married and see my grandson born, I dont want to give up yet, help

me.” Another woman

with stage III heart failure admitted the fear of death and loss: “My husband

and I knew each other since we were kids, but we only have been married for 10 years.

I wish we have more years to be together. I dont want to die, he would be lost

without me. Can your program help me go in the right direction?” Patients who had experience caring

for relatives with heart failure or other chronic conditions were more

interested in participating the study. One patient said, “My husband died from heart

failure, I still kept his weight charts....that was hard....I wish I had known

more about [heart failure].....now it is my turn....” Believing in and practicing lifestyle medicine Patients who had higher health literacy and actively engaged

in self-management behaviors were more attracted to the study. One patient

shared, “I am already doing this stuff on my own [eating a low salt diet,

taking pills as prescribed, being active, weighing myself every day, and going

to scheduled doctor appointments], I would love to get free support and

monitoring from your study.” Another patient subscribed to American Heart

Association newsletters and followed the posted heart healthy diet

instructions. He testified to the fact that engaging self-management behaviors

saved his life: “My doctor told me I had a year to live seven years ago. Now I

am still here because I changed the way I used to live...I believe I can live a

long, healthy life with heart failure. Id like to sign up for your program.” The

participants who benefited from the program were also likely to complete the

study. One patient told the interventionist, “I can breathe better, walk

steadier, feel more energy after I lost all the water weight now”. The patients who had a tendency to

frequently utilize healthcare

facilities had greater acceptance to the program. One patient who was labelled

as a “frequent flyer” by emergency department nurses was enthusiastic to join

the study: “I feel better when I am around doctors and nurses because I have so

many problems. I went to 42 doctor appointments in the past year, everyone

knows me here, Id love to participate in your program.” Personal factors in promoting recruitment and retention Presence

of a support system Male patients living with a spouse

or a partner were more likely to join and complete the study. Many male

patients approached by the author admitted that they would not have

participated in this study without their spouses or partners. One patient said,

“My wife will cook the low salt food and watch my weight.” When approached by

the recruiter, another patient said , “you have to wait for my wife, she is

coming, ask her because she will be the one doing this, I will do what she

tells me.” Another patient

who lived with his girlfriend proudly announced , “ Sure, my friend will drive

me here to get lab tests done. ” One male patient admitted, “ My wife and

daughter think I should do this .” Some adult children asked the author to

enroll their parents to the program: “My mother has bad depression after my dads

gone, she pretty much isolated herself from others. We felt like we lost both

parents at the same time, she is not herself anymore. This weekly call will

help get her out of her depression mood and push her to interact with others

again.” Another patients daughter said, “my mother is the only thing God left

for me, I am not ready to let her go... ..I know she does not meet your

criteria, she is too old and too weak, but please take her, that will make her

feel better about herself, I want her around for many more years, call me

selfish, I dont care, I want to keep her...” Patients with positive attitudes

easily accepted the program. One veteran confessed, “ I know the damage is done

when I was young...those drinking and smoking did not do any good on my heart and

my veins, but Id like to make changes even though it might be too late .” Some Patients

participated in the study for

companionship. One woman lost her husband four years prior and her children lived

out of state. She said, “Honey, no one has talked to me for 6 months, someone

will call me every week? I am in.” Another woman completed the study stated, “I

felt good when called me regularly; I was expecting her calls when the

scheduled time came and talking to her made me feel she truly cares about me.” Chronic conditions like heart

failure not only have a large impact on society as a whole, but also on the

quality of life of the patients [9]. The number of rural residents with heart

failure and other cardiac conditions is expected to rise rapidly as a result of

increasing life expectancy [10,11]. Heart failure patients are more likely to

have other chronic conditions [11,12] and these patients are struggling to

manage their multiple chronic conditions [12]. Inadequate self-management

contributes to high healthcare

utilization (hospitalization and Emergency Department visits) and its

associated expenses. Eventually, the diseases debilitate the patients

capability to live at home independently and result in long-term care placement

[13]. Therefore, it is important to promote self-management knowledge and

skills in order to prolong independence and reduce the healthcare related

burden in an aging society. Identifying and developing effective strategies to

support self-management in rural communities requires more rural-based studies

to discover and add new evidence. However, greater challenges in conducting

research in rural settings result in the underrepresentation of rural

participants in research trials. Studies among rural cardiac patients generally

show poor participation rates of 30–50% [14]. Studies have shown that non-participants

differ significantly from study participants in terms of personal

characteristics, clinical profiles and self- management behaviors. The

non-participants were more likely to have low health literacy, inadequate

support and resources, lower adherence to self-management guidelines, poor

relationships with care providers, complex comorbidities and lower capacity of

self- management, leading to higher healthcare utilization and poorer quality

of life [15]. Clearly, the relationship between

the recruiter and the patient is a key factor in whether or not patients elect

to participate in studies. Using a local recruiter who has established

relationships with the patients and lives in the same community is an important

gateway to successful recruitment and retention in rural research. The PCP can

also play a critical role in recruitment and retention. To enhance the PCPs

engagement, we sent regular letters to update the PCP on the progress of the

program. The on-going and timely communication were maintained with the PCPs by

faxing or phoning abnormal lab results and discussing the special cases of high

risk subjects (e.g. lack of resources, non-adherence to self-management

guidelines, complex disease

profiles, and unfavorable family dynamic). The diagnostic testing were

performed at the doctors office to save the subjects trips to healthcare

settings. The study also helped establish rapport with the PCPs. The PCPs felt

more appreciated when they knew what was going on with their patients and were

more like to support the research. Some physicians converted from opponents to

supporters of the research and referred their patients to the program. One

physician said, “I dont feel lonely anymore because, for a long time, I thought

I was the only one fighting this forever lost battle [to get the patients to

engage and be accountable for their own health], now, we can do this together! ”

In addition, the complementary alliance between medical and nursing staff was

noted by the PCPs. Generally speaking, patients felt it was easier to share the

truth and “naughty thoughts” with the nurses than the physicians. They were more

openly to confess their unhealthy habits and non- adherence (e.g., smoking,

drinking, skipping pills), and expressed their disagreement with medical advice

and health information to nurses than to physicians. With the

assistance of nurses, physicians would have more comprehensive knowledge and

understanding of patients self-care needs, which is necessary to develop

tailored treatment plans to meet individual health needs as well as have a more

reliable evaluation of treatment outcomes. It must be recognized that inherent

limitation accompanies this original randomized control trial. First, many

heart failure patients would be good candidates for palliative care programs

due to their life-limiting advanced illness, complex self-management regimens

and disabled self-management capabilities. The current study was not designed

to meet the care needs of patients who were no longer capable of caring for

themselves. Unfortunately, there is no effective rural community-based,

hospital-initiated palliative

care program in place at this time. The author felt a strong desire and

professional responsibility to identify and develop an effective palliative

care program to meet the care needs of such patients to reduce the care burden

and relieve the agony of patients and families. Secondly, during the study, the

author witnessed how heart failure patients struggled to adhere self-management

guidelines in addition to caring for their other chronic conditions.

The intervention was specifically designed for patent with heart failure only.

In reality, most patients had other aging-induced illnesses (e.g., degenerative

joint diseases, pain,

neurological disorders). It was impossible and infeasible to exclude patients

with multiple chronic conditions. Instead, more generic intervention content should

be developed to meet patients needs in managing multiple chronic illnesses. So

far, the effectiveness of an intervention including multiple chronic illness

management guidelines has not been reported. Lastly, the author felt as though

the “wrong” patients were recruited to the study. The patients needed the most

help were reluctant to participate due to various challenges. The study was more

attractive to those patients who had already actively been involved in lifestyle

modification behaviors, who were active learners and seekers of health promotion

information, or those who experienced the benefits of self-management outcomes.

This selection bias inevitably affected the study results. For instance, if such

motivated subjects were randomly assigned to the control group, they would

lessen the differences in self-management outcomes between the intervention and

control groups, therefore washing out the intervention effect. If the active

subjects were assigned to the intervention group, it would cause the ceiling effect

because their existing practice would leave little room for improvement by the

intervention. The limitations acknowledged above

with respect to study design, intervention content and targeting population

also provide direction for future research. First, there is a need for research

in rural communities to identify, develop and implement effective palliative

care programs to meet the care needs of patients with advanced heart failure

and other comorbidities.

Second, when developing education information to promote self-management adherence,

researchers and clinicians need to take into account the fact that older adults

are often juggling multiple treatments for various conditions. Close attention

must to be paid to avoid any conflicting information. Rather than adding the

education information for various illnesses together, an integrated,

comprehensive self-management instruction should be tailored to meet each

individuals needs. Last, recognizing the recruitment bias and the impractical

requirement of large sample size in conducting randomized control trials,

alternative research methods (e.g., mix methods, observational study, secondary

analysis with population-level data) should be utilized to provide

complementary evidence, leading to better care and better health outcomes. The challenges of recruiting and retaining

rural heart failure patients to participate in research to promote self-management

adherence are substantial, which reflects the barriers they face in engaging in

self-management practice. These barriers provide opportunities for clinicians and

researchers to work together to develop and implement effective programs to promote

self- management practice in heart failure patients

living in rural communities. Research reported in this publication

was supported by the National Institutes Nursing Research of the National

Institutes of Health under award number 1R15NR 13769-01A1. The sponsor had no

role in conducting the study, preparing and disseminating the study results.

Dr. Lufei Young is the recipient of the funding provided by the National

Institutes Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health. She has full

access to the study data and takes responsibility for their integrity and the

accuracy of the data analysis. 1. Giamouzis G. Hospitalization

epidemic in patients with heart failure: Risk factors, risk prediction,

knowledge gaps, and future directions (2011) J Card Fail.17:54. Lufei Young, University of Nebraska

Medical Center, College of Nursing-Lincoln Division, 1230 “O” St. Suite 131, PO

Box 880220, Lincoln, NE 68588-0220, USA E-mail: lyoun1@unmc.edu Young L (2016) Conducting BehavioralIntervention Research in Rural Communities: Barriers and Strategies to

Recruiting and Retaining Heart Failure Patients in Studies. NHC 101: 1-8 Research recruitment, Research

retention, Behavioral research, Heart failure, Self-management, Rural HealthConducting Behavioral Intervention Research in Rural Communities: Barriers and Strategies to Recruiting and Retaining Heart Failure Patients in Studies

Abstract

Full-Text

Background

Methods

Data Collection Process

Data Analysis

Results

• Perceived research burden and life interruptions,

• Lack of understanding or misunderstanding the research

• Mistrust Health Related Factors

• Muttiple cornorbidities

• Negative feelings and outlook

• Low health literacy Personal Factors

• Reluctant to engage in

self-management behaviors

• Accessibility

• Lack of resources and support

• Multiple demands in life Perceived

research burden and life interruptions

Mistrust

Health related barriers to

participating in research Multiple comorbidities

Negative feelings and outlook

Low health literacy

Personal barriers to participating

in research

Accessibility

Multiple demands in life

Research related factors that

promote recruitment and retention

Provider engagement

Previous research experience

Health related factors that promote

recruitment and retention Desire and motivation to change

Previous experience with self-care

of chronic disease

People with healthcare seeking behavior

Positive outlook and attitude

Feelings of loneliness

Discussion

Implication for Developing Research

Recruitment and Retention Strategies

Limitations

Future Directions

Conclusion

Acknowledgement

References

2. Manning S. Bridging the gap

between hospital and home: A new model of care for reducing readmission rates in

chronic heart failure (2011) J Cardiovasc Nurs.

3. Caldwell MA, Peters KJ, Dracup KA.

A simplified education program improves knowledge, self-care behavior, and

disease severity in heart failure patients in rural settings (2005) Am Heart J.

150:983.

4. Brueton VC, Tierney J, Stenning

S, et al. Strategies to improve retention in randomised trials (2013) The

Cochrane Library.

5. Treweek S, Lockhart P, Pitkethly

M, et al. Methods to improve recruitment to randomised controlled trials:

Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis (2013) BMJ Open 3:10.

6. Paul CL, Piterman L, Shaw J, et

al. Diabetes in rural towns: Effectiveness of continuing education and feedback

for healthcare providers in altering diabetes outcomes at a population level:

Protocol for a cluster randomised controlled trial (2013) Implement

Sci.8:30-5908-8-30.

7. Befort CA, Bennett L, Christifano

D, Klemp JR, Krebill H. Effective recruitment of rural breast cancer survivors

into a lifestyle intervention (2015) Psycho-Oncology. 24:487-490.

8. Tanner A, Kim S, Friedman DB, Foster

C, Bergeron CD. Barriers to medical research participation as perceived by

clinical trial investigators: Communicating with rural and african american

communities (2015) J Health Commun 20:88-96.

9. Garin O, Herdman M, Vilagut G, et

al. Assessing health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure: A

systematic, standardized comparison of available measures (2014) Heart Fail

Rev. 19:359-367.

10. Hicken BL, Smith D, Luptak M,

Hill RD. Health and aging in rural america (2014) Rural Public Health: Best

Practices and Preventive Models. 241.

11. Ho TH, Caughey GE, Shakib S.

Guideline compliance in chronic heart failure patients with multiple comorbid

diseases: Evaluation of an individualised multidisciplinary model of care

(2014) PloS one.9:e93129.

12. Dickson VV, Buck H, Riegel B.

Multiple comorbid conditions challenge heart failure self-care by decreasing

self-efficacy (2013) Nurs Res.

62:2-9.

13. Gozalo P, Teno JM, Mitchell SL,

et al. End-of-life transitions among nursing home residents with cognitive

issues (2011) N Engl J Med. 65:1212-1221.

14. Cudney S, Craig C, Nichols E,

Weinert C. Barriers to recruiting an adequate sample in rural nursing research

(2012) Online Journal of Rural Nursing and Health Care 4:78-88.

15. Glasgow RE, Strycker LA, Kurz D,

et al. Recruitment for an internet-based diabetes self-ma nagement program: Scientific

and ethical implications (2010) Ann Behav Med 40:40-48*Corresponding author

Citation

Keywords