Research Article :

Maternal health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being of the mother; it is a resource for everyday life of the mother. It encompasses the health care dimensions of family planning, preconception, prenatal, and postnatal care in order to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality. The use of antenatal, delivery and postnatal care services can be accessed through the number and timing of ANC visits, proportion of births delivered in health centers, attendants during delivery and antenatal care and number of postnatal visits. Health care services during pregnancy and after delivery are important for the survival and well-being of both the mother and the infant. The overall objective of this study is to investigate the perceived physical barriers to maternal health seeking behavior of rural women in Raya Alamata district. The researcher employed mixed research methods (both qualitative and quantitative). The study populations were reproductive women in the age category of 15-49. In doing so, a sample of 359 reproductive women was selected from three "Tabias‟ by using simple random sampling techniques. The qualitative data analyzed using thematic analysis whereas the quantitative data analyzed using descriptive statistics. Based on the finding this study, the majority of the respondents 31% were found between the age category of 25- 34 years, 87.5% were married, 93.6% belongs to Tigrian ethnic groups, 71.6% are followers of orthodox Christian, 60.7% were illiterate; and the majority 44.7% of the respondents earned an average monthly income of 501-1000 birr. Rural women also travelled 3.87 km, 5 km, 10 km and 6.4 km in average to get maternal health services from health posts, health centers, hospitals and private clinics respectively. Moreover, long distance and lack of transportation, inequitable distribution of health facilities, inconvenient topography and weather related problems were the major barriers for rural women to get maternal health services. These perceived physical barriers have affected the treatment seeking behavior of rural women especially throughout pregnancy, delivery and postnatal stages. The findings of this study give much emphasis into the perceived physical barriers to maternal health seeking behavior among rural women. The physical barriers restrained rural women from getting antenatal, delivery and postnatal care services which led to pregnancy complications, home delivery, and post-delivery problems which resulted in maternal morbidity and mortality.

Maternal

health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being of the

mother; it is a resource for everyday life of the mother [1]. Maternal health

comprises the health of women during pregnancy,

childbirth, and the postpartum period [2]. It encompasses the health care

dimensions of family planning, preconception, prenatal, and postnatal care in

order to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality [3]. The use of antenatal,

delivery and postnatal

care services can be accessed through the number and timing of ANC visits,

proportion of births delivered in health centers, attendants during delivery

and antenatal care and number of postnatal visits [4]. Health care services

during pregnancy and after delivery are important for the survival and wellbeing

of both the mother and the infant. Skilled care during pregnancy, childbirth,

and the postpartum period are important interventions in reducing maternal and

neonatal morbidity and mortality [5]. If

this is the case, it is important to give women-friendly health services. The

maternal health services must be available, geographically accessible,

affordable, and culturally acceptable in order to reduce maternal morbidity

and mortality.

Services should include Essential

Obstetric Care (EOC) at the primary and referral levels in order to

minimize delays in deciding to seek care, reach a treatment facility, and

receive adequate treatment at the facility. Besides, all women should have

access to a skilled attendant during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum

period. This attendant should be able to provide basic EOC and refer women to

comprehensive EOC, in case of complications. No woman should be denied access

to life-saving essential obstetric care when complications occur during

pregnancy or childbirth [9]. Access

to health services has to be guaranteed for all people throughout the world;

however, it is not yet fully achieved in many developing countries, particularly

in rural areas [10,11]. In Ethiopia, the utilization of health services is low

due to limited availability of maternal health services, poor service quality and

unaffordable costs to the client [8]. Moreover, there are also other common

barriers that contribute to the low utilization of maternal health services

includes lack of compliance of services with defined standards, the shortage of

supplies, infrastructure problems, deficiency in detection and management of

complications or emergency cases, and poor client-provider interaction.

Furthermore, services are also underutilized when they are perceived to be

disrespectful of womens

rights and needs, or are not adapted to the cultural contexts [9]. The

other problem is related to power consists of restrictions on womens access to

resources such as land, credit, and education limit their engagement in

productive work, constrain their ability to seek health care, and deny them the

power to make decisions that affect their lives. Even when women do seek health

care, they face high opportunity costs. They must give up time that they would

normally spend on household chores such as caring for children, collecting

water and fuel, cooking, cleaning, doing agricultural work, and engaging in

trade or other employment. These restrictions and other human rights abuses are

pervasive, and they relate, in part, to gender inequities and can impede

progress in improving maternal health outcomes among the poor [12]. In

addition to this, poor geographic access has been identified as one of the

major barriers facing rural women in seeking and using life-saving maternity

care services in many developing countries including Ethiopia [13,14].

Geographic access, the distance (or time) needed in order to reach a health

facility, is not only a direct physical barrier that precludes women from

reaching health institutions but it also affects even the decision to look for

care. It could have more influence in rural areas of Ethiopia, where it is norm

to see women in labor being carried on mens shoulder traveling many km to reach

a health facility [15]. Women in rural areas often walk more than an hour to

the nearest health facility. Poor road infrastructure and lack of reliable public

transport or access to emergency transportation make access difficult,

especially when obstetric complications occur [16]. Therefore,

the most important objective of this study is to identify the major perceived

physical barriers to maternal health seeking behavior among rural women of Raya

Alamata district. It is also hoped that the results of the study is essential

to policy makers to identify the major physical

barriers like distance, transport related problems, inequitable

distribution of health services, weather and topography. Last not least, it

also served as a foundation for any possible intervention aimed at reducing the

physical barriers that affect the maternal

health seeking behavior of rural women of the study area. Raya

Alamata is located at 600 km north of the capital city Addis Ababa and about

180 km south of the capital city of Tigray Regional State, Mekelle. It is the

south most administrative district of Tigray Region State bordered in the south

with the Amhara Regional State in the east with Afar regional State in the

North East with Raya Azebo woreda and in the North with Oflla woreda. Alamata

woreda has 15 tabias (peasant associations) and 2 town dwellers associations.

The number of agricultural households of the woreda is approximately 17,597.

The total population of the woreda was 128,872 in 2003/04 [17]. Regarding the

health infrastructure, the district had one hospital, six health centers and 13

health posts [18]. The

study is intended to explore the perceived

physical barriers that affect maternal health seeking behavior among rural

women in Raya Alamata district, southern Tigray. In doing so, a cross-sectional

study design is employed. Furthermore, the objective of the study requires the

integration of both quantitative and qualitative data to best answer questions

that cannot be answered by either of the two approaches alone. Therefore, the

study employs both data and methodological triangulation. The

target populations of the study are all women in the reproductive age group

(15-49 years) in Raya Alamata District. Particularly, the study focuses on 5467

households of the study area. Out of this, the researchers selected 359 samples

of women from Raya Alamata district based on simple random sampling technique.

The samples were selected by Kothari [19] sample size determination formula. On

the other hand, the informants for FGD, key informant interview and in depth interview

were selected by using purposive sampling. Focus

groups are a form of strategy in qualitative research in which attitudes,

opinions or perceptions towards an issue, product, service or programme are

explored through a free and open discussion between members of a group and the

researcher [20]. It is useful data collection method which helps to generate

qualitative data from the discussion by making group interaction between

members of the target population. The FGD helps to capture more deeper and

comprehensive information from respondents such as model women and males. Key

informant interview is used to collect qualitative data from informants that

have knowledge and experience on the issue of maternal health. This enabled to

get in-depth information from informants. Interview guide with loosely

structured conversation is used to collect data. This allows the interviewee to

respond flexibly and the interviewer to manage the core issues of the study. In

this study, nine model women, six health workers including health extension

workers, six religious leaders, three community leaders, were selected

purposively and interviewed. In-depth

interviewing is the most commonly used data approach in qualitative research.

In-depth interviews are those interviews that are designed to discover

underlying motives and desires. Such interviews are held to explore needs,

desires and feelings of respondents [19]. This method enabled the researcher to

generate highly detailed information and to have better understanding on the

perceived physical barriers to maternal health seeking behavior. In doing so,

in-depth interview is conducted with twelve women with the help of interview

guide check lists. The

data obtained from various sources is analyzed using both quantitative and

qualitative data analysis methods. The qualitative data was collected from

respondent using focus group discussion, key informant and in depth interview.

Qualitative data analysis is conducted concurrently with gathering data, making

interpretations, and writing reports [21]. The researcher listen all audio

taped and read the field notes step by step to jot down all the information.

After that the audio taped from FGDs, key informant interview and in depth

interview transcribed verbatim, and translate from Tigrigna to English. Then,

the translated data is organized, prepared, and broken up into sections based

on their themes. Then a technique of thematic analysis is used to interpret and

make sense of the organized data. In

the progress of research, researchers need to respect the participants and the

sites for research [21]. Thus, due respect was given to the participants during

the data collection process. Besides, an informed consent was received from

participants before the commencement of the interviews to ensure that

participation in research was voluntary. Respondents were informed that they

have the right to participate voluntarily and withdraw from the research at any

time. Anonymity of respondents and confidentiality of their responses were

ensured throughout the research process. Information that was provided by

informants would not be transferred to a third party or would not be used for

any other purpose. In

this part, the major findings of the study, based on the data obtained through

household survey; in-depth interview, key informant interview and FGD were

presented and discussed, in a descriptive way. Theories relevant to the

underlying themes and related literatures are used to interpret the primary

data. The

quantitative data is collected and analyzed on demographic and social

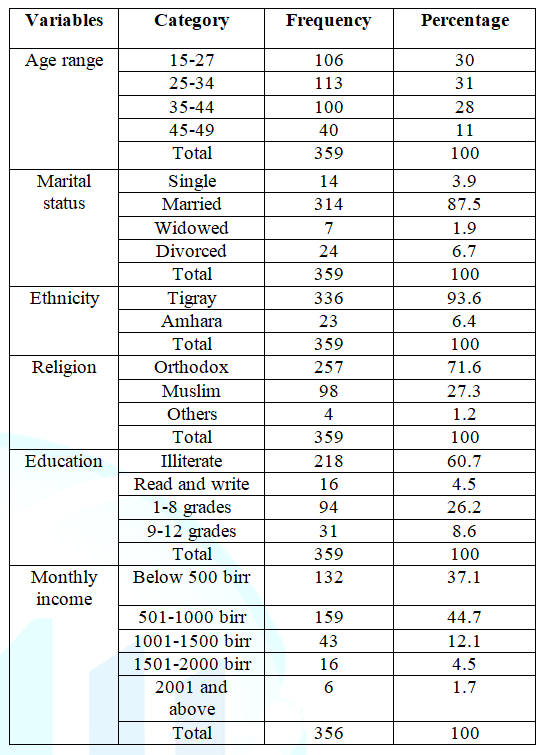

characteristics of sample respondents. As indicated in the Table 1, the socio demographic characteristics in this study

include age, marital status, ethnic identity, religious affiliation,

educational background and income of the respondents. In

this study, a total of 359 rural women aged 15-49 years were included. Out of

359 respondents, the majority 113 (31%) of women were found between the age

category of 25- 34 years. With regard to marital status, the majority of the

respondents 314 (87.5%) were married followed by divorced consists of 24

(6.7%). According to participants marital status of the respondents has an

association with maternal health seeking behavior. Being and becoming divorced

and widowed affect maternal health seeking behavior of rural women. Accordingly

divorced and widowed women were at risk, lack financial resources, lack

emotional, psychological and physical support; and are less likely to receive

maternal health care services than the married ones. Moreover, women FGD

participants also revealed that most divorced and widowed women were female

headed households who have different duties that restrained women from visiting

health facilities. Furthermore,

almost all respondents 336 (93.6%) belongs to Tigrian ethnic groups followed by

Amhara ethnic groups consists of 23 (6.4%). With regard to religious

affiliation, the majority of respondents 257 (71.6%) are followers of orthodox

Christian followed by Muslim 98 (27.3%). In relation to educational level of

respondents, 218 (60.7%) are illiterate, 94 (26.18%) are educated up to grade

eight, 31 (8.63%) are educated up to grade twelve; and the rest 16 (4.5%) of

the respondents are simply able to read and write. Another important indicator

for understanding the socio-economic status is the monthly income of the

respondents in the household. Out of 359 respondents, 159 (44.7%) of them earn

an average monthly income of 501-1000 birr, whereas 132 (37.1) of the

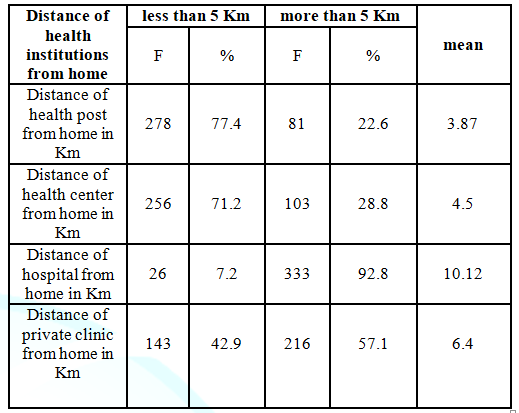

respondents earn less than 500 birr per month. In line with this, distance is an

obstacle for rural population of the study areas. The long distance of health

facilities from the dwelling of rural women is the main factor that can

influence a womans access to maternal health services. Similar to this vein,

the quantitative result in Table 2

revealed that out of 359 respondents, 278 (77.4%) were travelled less than 5 km

to arrive at the nearest health post whereas the remaining 81(22.6%) traveled

more than 5 km. This shows that the respondents travelled 3.87 km in average to

reach to the nearby health post to get maternal health services. With regard to

the distance of health center from home, 256 (71.2%) of the respondents were

travelled less than 5 km to reach the nearest health center and the rest 103 (28.8

%) of the respondent were travelled more than 5 km to reach the nearest health

center. In average, respondent travelled about 5 km to get to the nearest

health center. In addition to this, as the above

table indicates, more than 333 (92.8%) of the respondents travelled more than 5

km to get maternal health services from the nearby district hospital while the

rest 26 (7.2%) travelled less than 5 km. Respondents in average travelled more

than 10 kilometers to reach to the district hospital. Besides, more than half

216(57.1%) of the respondents were travelled more than 5 kilometers to get the

private clinic and 143 (42.9%) travelled less than 5 kilometer to reach the

nearest private clinics. They travelled 6.4 kilometer in average to reach the

private clinic to get medical treatments. In consistent with the above

findings, study by Zegeye [22] in rural Jimma, Horro District revealed that 189

(35.8%) of the mothers were found to live within 5 kilometer, 495 (93.8%) of

the mothers reside within 10 km walking distance of the nearest health center.

But these studies failed to identify the distance of the home to the health

facilities separately. The government is the main health

provider in Ethiopia but the coverage and distribution of its health facilities

among regions remains uneven. This weak infrastructure and limited distribution

systems in low income countries complicate access to health services,

especially in rural areas. Government health outlets may be relatively few and

widely dispersed resulting in uneven service availability within a country [27]. The absence of equitable

distribution of health institutions was one among the other problems that

challenge rural woman to get maternal health services. Based on government of

Ethiopian health strategy; the population health center ratio: the health

centers are adequate but it was not constructed at the appropriate places. In

supporting the above statement, one of the key informant interviewee, said: “In the rural area some health

facilities are not constructed at the hub of the Tabias. The health facilities

are concentrated at specific areas. They are not equally distributed. This was

difficult for those who have not health centers at nearby place because they travelled

long distance with difficult topography to get maternal health services. This

is not fair and it raises the question of equity (A 44 year old health expert

at Raya Alamata district health office)”. Finding from district health

workers revealed that health centers were distributed disproportionately at

Raya Alamata district. For instance, around Waja there were three health

centers in one cluster. On the other hand, in the highland areas of the district,

there was only one health center which has given health services to four

Tabias. Tabias that were found in one cluster like Selam Bekalsi, Limiat and

Hulu Giziye lemlem also have not any health center and they were used services

from the town health facilities. So this indicated that the distribution of

health centers was not equitably distributed across Tabias. Moreover, the key informants approved the existence of thirteen health posts in

the district but it was not constructed at the appropriate places. In support

of this argument, a 24 year key informant from Tabia Selam Bekalsi noted that: “For instance, at Tabia Selam Bekalsi the

health post is not found at the right places. The health post is found at one

margin of the Tabias which is not accessible to all population of the Tabia.

The health post is more accessible only to one village whereas the other

villages did not come and use the health post owing to long distance”. In general, these haphazard

distributions of health centers as well as health posts affect treatment

seeking behavior of rural women during pregnancy, delivery and postnatal

services. Rural women are being restricted to make contact with health care

providers. As a result the number visit to health facilities was reduced.

Besides, it has restrained rural women from using antenatal care services such

tetanus toxoid immunization, iron and folic acid. They were deprived of

accessing screening services for conditions and diseases such as anemia, STIs,

HIV and other pregnancy-related complications due to haphazard distribution of

health centers. In general, the geographical location of health facilities

affected the overall health seeking behavior of rural women at Raya Alamata

district. Qualitative data from FGD and key

informant also revealed that haphazard distributions of health centers also

contribute to home delivery under the supervision of Traditional Birth

Attendants or other relatives. It has also reduced the proportion of babies

delivered in a safe and clean environment under the supervision of health

professionals. The mother and the child affected by complications arising from

the delivery. Hence, this situation increases the risk of complications and

infections that may cause the death or serious illness of the mother and the

baby or both. The diversity of socio-economic environments,

climates, and terrains among regions in Ethiopia greatly impacts health

conditions and outcomes [27]. Other studies also showed that geography and

terrain were significant barriers to care seeking and utilization [28].

Besides, study conducted in Nepal also revealed that difficult geography was

the main reason for poor access to the birthing center. The terrain and long

walking hours for both women and services providers are well-known barriers to

accessing health services [14]. Similarly, topography of the area specifically

the mountainous nature is challenging for women to get timely maternal health

services specifically in the highland parts the district. In substantiating

this, key informant from Timuga health center noted that: “The topography of the area hinders women from attending

antenatal care services. Most women were tedious to have four visits to the

health facilities due to tough topography and distance. Then, the majorities

were made a decision to abstain from attending health facilities however some

women are tried to visit health facilities erratically [A 48 years of

midwife]”. As the above narration indicates,

topography of the area is considered as barriers for rural women to use

maternal health services. Due to its terrain nature of the physical

environment, women were discouraged to use antenatal care services. They had

turn down the amount of visits to health facilities. Some of them tried to

visit health facilities but it is not even. In addition to topography, a problem related to

climate is another barrier for a number of women to seek and use maternal

health services. In corroborating this idea, one of the respondents from Selam

Bekalse has said respectively as follows: “When

I gave birth to my first kid it was at the summer time…my family and the

Traditional Birth Attendant is waiting, at times, thinking she will give birth

after a while. But as time went on I have been in pain and I suffer a lot and

they went on thinking to take me to Alemata district hospital but in vain. This

is because there is no access to road during the summer time and the muddy

nature of the area has troubled us not to go. In the meantime, I began to labor

and give birth in the nearby vicinity with the help of God [45 years old FGD participant]”. As the above narration of the

woman indicated that labour and birth mother were forced to suffer from pain

why it happened is due to lack of access to road during the summer time and the

muddy nature of the area. The absence of road and muddy nature of the vicinity

restrained women from accessing maternal health services at the right time. Besides, women were forced to

give birth at home with the assistance of traditional birth attendant even they

did not like to do it. Similarly, another study also revealed that the absence

of road and muddy nature of the vicinity restrained women from accessing

maternal health services at the right time [26]. Besides, women were forced to

give birth at home with the assistance of traditional birth attendant even they

did not like to do it. Another study also showed that difficult terrain, poor

condition of roads, and unfavorable weather conditions such as rains and

snowfall sometimes influence their decision to use facility-based services.

They were also afraid of facing complications on the way to health facilities

as it might take long for them to reach there [29]. In line with this

literature, the informant stated the condition as follows: “I

know a woman in our village that had encountered a problem during the summer

time. For it Greb Etu, Hara and Greb Odo have been flooded. The family of the

pregnant woman and the accompanied neighbors were trapped because of the flood

to get medical assistance going to the nearby town and they turned back to home

to use any traditional measure for the delayed labor. Adding salt to injury,

the local Traditional Birth Attendants says the fetus is coming upside down and

she went to recommend making downward the pregnant woman using her to legs to

rearrange and upright the misplaced fetus structure. Fortunately enough, after

a couple of hours in labor, due to Gods assistance she has given birth. In a

nutshell, during summer time especially when the three rivers flooded we have a

lot of problem in our area to take pregnant women to health center [45 years

old FGD participant]”. This study has tried to assess

the perceived physical barriers to maternal health seeking behavior in Raya

Alamata district, Southern zone of Tigray region by giving a particular

emphasis on rural women. Accordingly, long distance and lack of transportation,

inequitable distribution of health facilities, inconvenient topography and

weather related problems were the major barriers for rural women. These

perceived physical barriers have affected the treatment seeking behavior of

rural women especially throughout pregnancy, delivery and postnatal stages. As

a result, the number visit to health facilities were reduced, they restrained

from using antenatal care services such tetanus toxoid immunization, iron and

folic acid; and they were also deprived of accessing screening services for

conditions and diseases such as anemia, STIs, HIV and other pregnancy-related

complications. Besides, they are forced to deliver at home without the

assistance of skilled birth attendants. This increases the risk of complications

and infections that may cause the death or serious illness of the mother and

the baby or both. I express my immense appreciation and thanks to

University of Gondar, department of Sociology. I am also thankful to my study participants

who gave me their full time, information and life stories with full interest

during the research. 1. Ann

Starrs. The safe motherhood action agenda; priorities for the next decade,

report on safe motherhood technical consultation (1997) Family Care

International Colombo, Sri Lanka. 2. WHO: Health topics (2011) Maternal

health. 3. WHO (2008) Maternal Health. 4. Situ

KC. Womens autonomy and maternal health care utilization in Nepal (2013)

University of Tampere, Finland. 5. Ethiopia

Demographic and Health Survey Report 2016 (2017) Ethiopian Central Statistical

Agency and ICF International Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, Maryland, USA. 6. MoHFW

(2009) Operational guidelines on maternal and newborn health, New Delhi, India. 7. Africa

progress panel Policy Brief. Maternal Health: Investing in the lifeline of

healthy societies & economies (2010). 8. CARE

Learning Tour to Ethiopia. Meeting MDG5: Improving maternal health (2010). 9. WHO/UNICEF/UNFPA.

Women-friendly health services experiences in maternal care (1999). 10. Shaikh

BT and Hatcher J. Health seeking behavior and health service utilization in Pakistan:

Challenging the policy makers (2005) J Public Health (Oxf) 27: 49-54. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdh207 11. Januga

DN, Gilbert C. Womens access to health care in developing countries (1992) Soc

Sci Med 35: 613-617. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(92)90355-T 12. Elizabeth

Lule, Ramana GNV. Nandini O, Joanne Epp, Huntington D et al., Achieving the

millennium development goal of improving maternal health: Determinants, interventions

and challenges (2005) Washington DC, USA. 13. Yanagisawa

S, Oum S and Wakai S. Determinants of skilled birth attendance in rural

Cambodia (2006) Trop Med Int Health 11: 238-251. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01547.x 14. Wagle

RR, Sabroe S and Nielsen BB. Socioeconomic and physical distance to the

maternity hospital as predictors for place of delivery: An observation study

from Nepal (2004) BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 4: 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-4-8 15. Maternal

Healthcare Seeking Behavior in Ethiopia: Findings from EDHS 2005 (2008) Ethiopian

Society of Population Studies, Addis Ababa. 16. Celik

Y and Hotchkiss R. The Socio-Economic Determinants of Maternal Health Care in

Turkey (2000) Soc Sci Med 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2393-4-8 17. IPMS.

Pilot learning site diagnosis & program design. Improving productivity

& market success of Ethiopian farmers (2005). 18. Rural

raya alamata district health office (2004) Annual report. 19. Kothari R. Research methodology: Methods and

techniques: 2nd edn (2004) New Age International (p) Ltd., New

Delhi, India. 20. Kumar

R. Research methodology a step-by-step guide for beginners: 3rd edn

(2011) SAGE Publications Ltd., Los Angeles, USA. 21. Creswell

JW. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches 3rd

edn (2009) SAGE Publications Inc, Los Angeles, USA. 22. Zegeye

K, Gebeyehu A and Melese T. The role of geographical access in the utilization

of institutional delivery service in rural Jimma Horro District Southwest

Ethiopia (2014) Primary Health Care 4: 150. https://doi.org/10.4172/2167-1079.1000150 23. Kaji

T Keya, M Moshiur Rahman, Ubaidur Rob and Benjamin B. Distance travelled and

cost of transport for use of facilitybased maternity services in rural

Bangladesh: A cross-sectional survey (2013) The Lancet 382. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62178-9 24. Ononokpono

N. Determinants of maternal health-seeking behaviour in Nigeria: A multilevel

approach (2013) University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. 25. Zeleke

A. An assessment of factors affecting the utilization of maternal health care

service delivery: The perspective of rural women in the case of duna woreda,

hadiya zone (2015) Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa. 26. Thaddeus

S and Maine D. Too far to walk: Maternal mortality in context (1994) Soc Sci

Med 38: 1091–1110. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536%2894%2990226-7 27. Chaya

N. Poor access to health services: Ways Ethiopia is overcoming (2007)

Population Action International 2: 1-6. 28. Khatri

RB, Dangi TP, Gautam R, Shrestha KN and Homer CSE. Barriers to utilization of

childbirth services of a rural birthing center in Nepal: A qualitative study

(2017) PLOS ONE 12: 0177602. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177602 29. Riaz

A, Zaidi S and Khowaja AR. Perceived barriers to utilizing maternal and

neonatal health services in contracted-out versus government-managed health

facilities in the rural districts of Pakistan (2015) Int J Health Policy Manag

4: 279–284. https://doi.org/10.15171/ijhpm.2015.50 30. Nyathi

L, Tugli AK, Tshitangano TG and Mpofu M. Investigating the accessibility

factors that influence antenatal care services utilisation in Mangwe district,

Zimbabwe (2017) Afr J Prm Health Care Fam Med 9: 1337. https://dx.doi.org/10.4102%2Fphcfm.v9i1.1337 Hayelom Abadi

Mesele, Department of sociology, College of Social

Sciences and Humanities, Dessie, Ethiopia, E-mail: abadihayelom129@gmail.com

Mesele HA. Perceived

Physical Barriers to Maternal Health Seeking Behavior among Rural Women: The

Case of Raya-Alamata District, Southern Tigray, Ethiopia (2018) Nursing

and Health Care 3: 47-52 Delivery Care, Ethiopia, Maternal Health, Physical Barriers, Postnatal Care, Rural Women

Perceived Physical Barriers to Maternal Health Seeking Behavior among Rural Women: The Case of Raya-Alamata District, Southern Tigray, Ethiopia

Abstract

Introduction: Full-Text

Introduction

Maternal health is important to communities, families and the nation due to its

profound effects on the health of women, immediate survival of the newborn and

long term well-being of children, particularly girls and the well-being of

families [6]. As an investment in maternal health is an investment in health systems.

These investments help to improve the health of pregnant

women, as well as the health of the general population. Healthy mothers

lead to healthy families and societies, strong health systems, and healthy

economies. As one step towards achieving these results, there are proven

cost-effective interventions that can dramatically improve maternal care in

Sub- Saharan Africas health systems. Investing in maternal health is urgent:

not only because giving life should not result in death, but also because women

are important economic drivers and their health is critical to long-term,

sustainable economic development in Africa. Furthermore, investing in maternal

health is a way to improve health systems overall, which benefits the entire

population of a country [7]. Furthermore, strong maternal health investments

are a key to ending poverty and improving the status of women [8]. Research

Methodology

Description of

the Study Area

Research Methods

Study Population

and Sampling Method

Focus Group

Discussion (FGD)

The researcher conducted three FGDs one from each Tabias. Each FGD participants

are selected based on purposive sampling technique and each discussion

comprises eight members. Therefore, a total numbers of study participants

addressed with FGD are 24. These were organized for women (both model and non-model

womens) and husbands/males respectively. The discussion with the participants

of the FGD was based on discussion guide that were structured around the key

themes by using local Tigrigna language to avoid misunderstandings. Besides,

the moderator was sensitive to local norms and customs during discussion.

Before the commencement of the discussion, the moderator specified the

objective of the FGD and guides the discussion accordingly. Key Informant

Interview

In-depth

interview

Methods of Data

Analysis

On the other hand, the quantitative data was processed as an important part of

the whole survey operation. It includes editing, coding, data entry, data

cleaning and consistency checking. A Statistical Package for Social Sciences

(SPSS, version 20) was used to analyze the data. The researcher used

descriptive statistical tools to analyze the quantitative data. Descriptive

tools such as frequency, percentages, and graphs are employed to present the

results. Finally, the quantitative findings are used to substantiate the

qualitative findings. Ethical

Consideration

Results and

Discussion

Socio-Demographic

Characteristics of Respondents

The Influence of

Distance and Lack of Transport on Maternal Health Seeking Behavior

On the other hand, the research result revealed that distance to health

facility and means of transportation are major obstacles to service utilization

[23]; it has been observed as an important factor that can influence a womans

access to health care [24] and it was consider as a major reason for rural

women for non-attendance of antenatal and postnatal care services [25].

Likewise, in this study, distance was one among the major hindrance for rural

women. The absence of roads also makes the distance and travelling times so

long and unsafe for rural women. In rural areas of the study area, distance and

lack of transportation were the major blockades to utilize maternal health

services like antenatal, delivery and postnasal care services. As a result of

this, a number of women were travelling very long distance frequently on foot

to reach the nearby health

facility. This is still a problem to access health facilities for women

residing far away from health facilities at Raya Alamata district. Likewise,

Thaddeus and Maine [26] in their studies found that distance to health services

exerts a dual influence on use, as a disincentive to seeking care in the first

place and as an actual obstacle to reaching care after a decision has been made

to seek it. Many pregnant women do not even attempt to reach a facility for

delivery since walking many km is difficult in labour and impossible if labour

starts at night, and transport means are often unavailable. Those trying to

reach a far-off facility often fail, and women with serious complications may

die en route. Inequitable spatial distribution of

health facilities and its influence on maternal health seeking behavior

The influence of Topography and Weather

on maternal health seeking behavior

Concomitantly, the topography of the area is considered as barriers for rural

women to use maternal health services. Due to its terrain nature of the

physical environment, rural women were discouraged to use antenatal care

services. They had turn down the amount of visits to health facilities. Some of

them tried to visit health facilities but it is not even. This negatively

affects the overall maternal health utilization in general and maternal health

seeking behavior in particular.

Heavy rain and flooding were the major barriers for rural women during the

rainy season to get maternal health services from modern health facilities at

the right time and place. During this season, everything is hard for women

because of the cold summer seasons at some parts of Raya Alamata district. In

this season, the rural roads were covered with mud and become difficult for

ambulances to transport labour women. So people forced to carry out women by

using traditional ambulances (stretcher) to the nearest dry areas or roads this

delays women from getting timely treatment and many of them delivered before

reaching to the health centers without the assistance of health professionals.

In line with this, studies in Zimbabwe revealed that during the rainy season

women are affected as they become immobile because of the lack of transport

[30]. Conclusion

Acknowledgment

References

*Corresponding author:

Citation:

Keywords