Research Article :

Background: Rural nursing practice and education remain a

difficult task to achieve in first world countries, let alone in a third world

country like Lebanon. The latter sustained 15 years of civil war, followed by

ongoing political and economic instability. North and South Lebanon, and Bekaa

are rural sites, and are considered the most socioeconomically-disadvantaged

geographic locations in the country. This includes severe shortage in Nursing

practice and education. Purpose: The aim of this study is to share the experience in

the provisional establishment of a School of Nursing in rural Lebanon, hoping

that such an initiative would help in lessening the severity in the shortage of

qualified nurses rurally, and, thus, in improving health care. Method: The model followed is based on four main pillars,

namely approaching the locals, establishing the matrix, designing the

curriculum, and setting-up research priorities. Each of these pillars consists

of various components at different levels. Results: Approaching the locals and establishing the matrix

are essentials and prerequisites for the other two main pillars. The former is

time-consuming, requires well-trained human resources, and takes a big

proportion of the time allocated to the project. Establishing the matrix,

designing the curriculum, and setting-up research priorities are

equally-important, and each has its own peculiarities and requirements that are

summarized in this manuscript. Setting-up a rural School of Nursing in Lebanon is not a privilege. It

is rather a necessity, and requires careful planning and allocation of

significant human and non-human resources. However, the experience is very much

enjoyable, has a unique flavor, and provides the best solution for the severe

shortage in qualified nurses from which the local villages suffer. Lebanon

is a small country with a landscape not exceeding 10,452 km2, and

with a population of 6,229,794 based on the 2017 statistics [1]. The urban

population accounts for 88.6% of total population [1]. Torn with political

instability, the country went through 15 years of civil war, followed by

ongoing socioeconomic hardships resulting in low income, high unemployment

rate, and poverty. Such indicators are even more pronounced in the rural

governorates or provinces (also called Mohafazats), namely North Lebanon, South

Lebanon, and Bekaa [2] (Figure 1). Figure 1: Map of Lebanon showing the various districts

(mohafazats or governorates). The

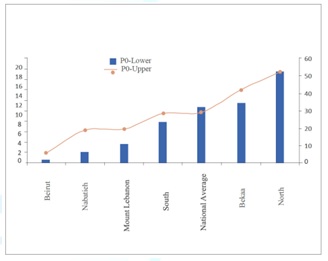

first post war official report on poverty, growth and income distribution in

Lebanon was published by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in

2008 [2]. The results showed an above average prevalence of extreme poverty in

Bekaa and the South (10-12%), an average prevalence of overall poverty in Bekaa

(29%), and an above average

prevalence of overall poverty in the South (42%). A very high prevalence of

extreme and overall poverty in the North (18% and 53%, respectively) was

reported [2] (Figure 2). The

UNDP report also showed that there is a lower likelihood of school and

university enrolment, attendance and retention for the poor residing in these rural

areas of Lebanon [2]. The gaps between poor and non-poor in enrollment

rates were found to widen from elementary to intermediate, secondary, and

tertiary education. Only one poor child out

of two is enrolled in intermediate schools, and only one poor child out of four

is enrolled in secondary schools [2]. The ratio becomes even worse in tertiary

education enrollment. The corresponding ratios for the non-poor are three

out of four for intermediate schools, and one out of two for secondary education.

Therefore, education seems to highly correlate with poverty in Lebanon, whereby

almost 15% of the poor population is illiterate, as compared to only 7.5% among

the non-poor. The unemployment

rate in the non-poor cohort is half the rate seen in the poor one.

Moreover, even if poor citizens were able to break the vicious circle of

education and poverty, and they were able to complete their education, they

could not enter the job market as easily as the non-poor ones.

The

health care services in rural Lebanon seem to follow the same above-mentioned

education and poverty trend [3]. According to the Planning Unit at the Lebanese

Ministry of Public Health, there are approximately 3,000 beds in the public

sector and 12,000 in the private one. Some of the former are not active,

which decreases the percent supply of active beds from the public sector [3].

Private hospitals do not deliver the same quality of services to the rich and

poor. The majority of private hospitals are general and multidisciplinary with

less

than 100-bed capacity. Traditional public hospitals are rather small

with

the largest ones having 70 active beds [3]. In addition, they are poorly

equipped and lack qualified personnel, namely registered nurses (RNs) holding a

Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN) degree. Lebanon continues to suffer from

a severe shortage in nurses in general, and RNs in particular. The ratio of

qualified nurses to 1000 population was 0.625 in 2002, 1.786 in 2007, and 2.562

in 2014, thus continues to be one of the lowest in the world [4,5]. The shortage

results from several reasons, including the unattractive professional status

(stigma), being mainly a female career, and a high turnover. Another major

reason for the severe shortage of nurses in the rural areas of Lebanon is the

low number in the Schools

of Nursing offering a BSN degree in these areas, as well as the poverty

described earlier, which limits the high school graduates from enrolling in

such degrees [2-5]. According to latest statistics released by the Order of

Nurses in Lebanon, the total number of nurses registered with the Order up

until the end of December 2017 was 15,034, of which 79.7% are females and 20.3%

are males [6]. The majority of the nurses are aged between 26 and 45. The ones

who are still in the workforce accounted for 73.4%, and those who hold a BSN

degree accounted for 50.1% only. The distribution of these nurses in rural

Lebanon was 14.7% in the North, 9.3% in Bekaa, and 14% in the South. The

majority (84.6%) of these nurses work in hospitals, a very small percentage

(4.7%) in medical centers (primary care, clinic, infirmary, public health

outlet, dispensary, midwifery,

maternity, rural

health), and even a smaller percentage (1.4%) in schools or nurseries

[6]. South Lebanon consists mainly of agricultural

villages and communities, with the major local towns being Saida, Tyre, and

Nabatieh (Figue 3). It has a

population of 816,541 inhabitants, and an area of 1988 km² [1]. Based on the

situation analysis summarized in this introduction, and as an attempt to meet

the needs of the local communities in South Lebanon, Phoenicia University was

established in the District of Zahrany, south of the Litani river. Its main

goal is to provide quality

tertiary education at an affordable fee, be it for the residents of this

rural governorate (province) or for any student residing in the other rural

governorates (provinces) in Lebanon. Since serving the community is among the

vision and mission of the university, and based on the severe shortage in

qualified RNs in South Lebanon, a decision was recently taken by the university

to plan a School of Nursing with a unique program that is

community-based-rural-health-oriented. This paper summarizes this plan, and

could be used as a platform for planning other rural Schools of Nursing in the

outback. Figure 3: Map of Lebanon

listing the various cities and towns. ArabiaGIS 2008. Planning a Rural

School of Nursing

This section summarizes the

process followed in the provisional establishment of a rural School of Nursing

at Phoenicia University. The model we followed consists of four main pillars,

each containing various components at various levels. Approaching

the Locals

Rural communities differ from the

urban ones, and so do the facilities available [7]. Understanding the culture,

tradition, and mentality of the rural communities are the key to any successful

project to be launched in the area, let alone establishing a university degree

in Nursing [8-12]. Such an understanding is only achieved by meeting the

individuals and their extended families, the farmers, the school principals and

teachers, the educated and uneducated

residents, the chiefs of the villages who are often the presidents of both

the villages municipalities and their extended families, the directors and

senior staff of the local

hospitals and medical centers, the financial sector, and the religious

leaders (priests and sheikhs). Such meetings provide a valuable insight, and

help in feeding a multilevel database in relation to what the local health care

needs are, disease prevalence, and how the new degree program could be designed

to help in meeting those needs. As such, they abet in validating the professional

and academic relevance, the continuous need for the Nursing

program, the feasibility for a new School of Nursing, the financial

liability and viability (how much of the income, expenditures and share of

resources that the Nursing program has could affect room for expansion and

program stability, and endowments and financial aid programs for students,

including scholarships, loans and grants), and the available overall resources.

The meetings also help in setting up the context within which the Nursing

program will exist, positioning the goals, categorizing the curriculum content,

framing the curriculum, forecasting for instruction, and structuring

evaluation.

Establishing

the Skeleton Matrix Having

identified the needs of the local communities in South Lebanon, a matrix is set

up to align those needs with the appropriate skeletons [8-12]. The latter

include the parent institution and its philosophy and mission in relation to

education, service and research/scholarship. They also include the physical

space and infrastructure on campus to be allocated for the new degree program,

such as lecture halls, laboratories, simulation and virtual

clinic facilities, library and student services, academic services, and

instructional technology support (distance education resources). The

potential faculty and student characteristics, the economic situation and its

impact on the curriculum, and a comprehensive outline of the health care system

to maintain the curriculum are other skeletons to focus on. In addition,

commuting of students, faculty and support staff is an essential skeleton to

carefully consider. Other major skeletons include partnership of the degree

program with the primary, secondary, and tertiary

health care facilities available in the region, be it government

institutions or private ones. These facilities will serve as clinical attachment

(clerkship, practicum) sites for the potential nursing students, and, as such,

will play a vital role in ensuring that the students have developed the

competencies required to safely practice the profession upon graduation.

Another

important skeleton is the demographic information gathered during the

above-mentioned meetings, such as age, sex, education levels, language (Arabic,

French, and English), socioeconomic status, etc. This information helps in

identifying potential students and their characteristics, the demands of the

population that the graduates will serve, and the nature of the curriculum to

be designed (adult versus young learning theories and modalities). For

instance, the current shortage in RNs holding a BSN degree indicates the possibility

for an accelerated program, and the current shortages in nursing specialties

necessitate advanced

practice curricula which provide the RNs with opportunities for continuing

education. This demographic information also helps in identifying existing and potential

part-time and full-time faculty, adjunct faculty, clinical instructors, and

clinical preceptors, and how their research

and educational credentials compare to others. Still another important

skeleton is benchmarking. This is to compare the program against those offered

by other Schools of Nursing nationwide, regionally, and internationally.

Comparison indicators to be used include pass rate on the Lebanese Nursing

National Licensing Exam or Colloquium, accreditation, graduate employment

rates, national and international reputation, admission and retention rates,

and costs of the program, to name a few.

Establishing

an Advisory Board for the new program is an essential skeleton too. Members of

the Board should include the Dean or Director of the Program, the Chancellor,

the President of the university, a representative from the Board of Trustees,

the President of the Order of Nurses in Lebanon, representatives from both the

Lebanese Ministries of Public

Health and Higher Education, senior officials from international (North

American, Australian, European) Schools of Nursing, directors of the local

public and private hospitals and medical centers, and representatives from the

student body, faculty, community, and major businesses in the region. Detailed

policies and procedures for the whole program is written and revised, and an

analysis of the structure of the parent institution and that of the Nursing

program is set in place to describe the hierarchal and formal lines of

communication. Various levels of steering committees and subcommittees,

including Nursing curriculum committee, college curriculum committee, and

university curriculum committee are set in place as well.

The

Curriculum

The

proposed curriculum is a community-based-rural-health-oriented

one [11,12]. It consists of nine intensive semesters (fall, spring, and

summer), and is based on credit hours. Content delivery will be through

Problem-Based Learning (PBL), Team-Based Learning (TBL), Evidence-Based Nursing

(EBN), didactic lectures, practical laboratory sessions, simulation sessions,

and bed-side teaching through clinical rotations in primary, secondary, and tertiary

health care settings. Basic, clinical, and human

sciences will be integrated vertically and horizontally throughout the

curriculum. In addition to the generic health topics often taught in a BSN

degree, emphasis will be on the common diseases and disorders identified in the

visited communities and in the epidemiological health indicator database,

including incidence, prevalence, birth and death rates, maternal and infant

mortality rates, risk factors, occupation, etc. Formative and summative

assessments will be used at all time, and a competency checklist, a logbook,

and a portfolio focusing on knowledge, clinical skills, attitude, ethics, communication

skills, research, and professional development will be accompanying the

students from day one. External examiners will be invited at the end of each

semester, and will act as both independent examiners of the students and

evaluators of the program. Throughout the curriculum, each learning activity

will be linked to a quick and short online evaluation form to be filled in by

the students. All the teaching staff will also fill in a short and quick online

feedback form, which the students could access to monitor their academic

performance. A faculty-student retreat will be conducted at the end of each

academic year to reflect on both the contents and processes pertaining to the

curriculum and degree program. Rural

Health Nursing Research

Integration

of rural health nursing research in our curriculum is paramount. This is based

on the fact that bridging scholarship and research in Nursing could evolve into

evidence-based Nursing practice [13-16]. In fact, such bridging could cross all

disciplines, and could lead to interprofessional collaboration and

evidence-based practice, based on the newest breakthroughs and research in

health care Nursing and education. It plays an increasingly important role in

its contributions to Nursing

practice, specifically to the professional postgraduate degrees in Nursing

(MSN, DNP, PhDN). Again, the initial community visits described earlier provide

a realistic database in both listing and prioritizing research topics in nursing

to be integrated into the curriculum. This is based on the fact that

partnerships between community members and academic investigators are essential

to the success of human studies in rural communities. For instance, research to

explore the holistic impact of a rural health problem depends on questions

queried by community members living with the direct physical, spiritual,

social, emotional, and/or economic effects of exposure. The research topics

added to our database include costs of hospital admission and stay, medications

and doctor consultations. They also include pre-marriage counseling, womens

health, mental health, mens health, occupational health and job security,

general health care ease-of-access and remoteness for the elderlies, oral

health, village health and wellbeing, primary care, rural ageing, nutrition,

child health and wellbeing, rural

health education and service delivery, cultural and social aspects of rural

health, accidents and emergency, and chronic diseases and palliative care. Studies have shown that no matter

what the incentives are in recruiting qualified nurses to rural regions, the

best solution remains to establish a Nursing

degree program in these regions, and to recruit Nursing students from the

locals [17]. This ensures that an optimal number of qualified nurses will be

retained to serve the rural disadvantaged communities from which these nurses

originate.

We summarized in this manuscript

a model for establishing a BSN degree in rural Lebanon. The model is based on

four pillars, each containing various components that need to be addressed

thoroughly and at different levels. We follow at Phoenicia University a motto

that states that “leaders are not born, they are crafted”. Such a motto

summarizes our universitys overall philosophy, vision, and mission. It has been

translated in many shapes and forms by the university since its inception, the

latest being the decision to establish a unique rural School of Nursing in

Lebanon. The challenges are many, especially with the poor

economy and health care system from which the whole country has been

suffering for years, let alone the rural areas. However, the university

believes that it has an obligation to serve the rural communities all over

Lebanon, and that when there is a will there is a way.

1. World population prospects: The

2017 revision (2017) Department of economic and social affairs, Population division

volume II: Demographic profiles, UN, New York, USA. 2.

Laithy HE, Abu-Ismail K and

Hamdan K. Poverty, growth and income distribution in Lebanon (2008) United

Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UN, New York, USA. 3.

Health systems profile (2006)

Regional Health Systems Observatory- EMRO, Lebanon. 4.

Ammar W. Health system and reform

in Lebanon (2003) WHO, Beirut, Lebanon. 5.

Density of nursing and midwifery

personnel (total number per 1000 population) (2018) WHO Global Health

Observatory. 6.

Order of nurses in Lebanon (2017),

Lebanon. 7.

Spoont M, Greer N, Su J, Fitzgerald

P, Rutks I, et al. Rural vs. Urban ambulatory health care: A systematic review

(2013) CreateSpace independent publishing platform, Washington DC, USA. 8.

Johnson M. Intentionality in

education (1977) Lebanon. 9.

Lohmann A and Schoelkopf L. GIS -

A useful tool for community assessment (2009) J Prev Interv Comm 37: 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1080/10852350802498326 10. Walker A, Bezyak J, Gilbert E and

Trice A. A needs assessment to develop community partnerships: Initial steps

working with a major agricultural community (2011) Am J Health Ed 42: 270-275. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325037.2011.10599197 11. Charlene

AW and Helen J Lee. Rural nursing: Concepts, theory, and practice 4th

edn (2018) Springer publishing company LLC, New York, USA. 12. Sarah

BK. Curriculum development and evaluation in nursing 3rd edn (2014) Springer

publishing company LLC, New York, USA. 13. Aduddell

KA, and Dorman GE. The development of the next generation of nurse leaders

(2010) J Nurs Ed 49: 168-171. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20090916-08 14. Evans

N, Michelle L and Komla T. A systematic review of rural development research:

characteristics, design quality and engagement with sustainability (2015)

Springer International Publishing, New York, USA. 15. Anderson

CA. Current strengths and limitations of doctoral education in nursing: Are we

prepared for the future? (2000) J Prof Nurs 16: 191-200. https://doi.org/10.1053/jpnu.2000.7830 16. Udlis

KA and Manusco JM. Doctor of nursing practice programs across the United

States: A benchmark of information. Part I: Program characteristics (2012) J

Prof Nurs 28: 265-273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2012.01.003 17.

Gisèle M, Gagnon MP, Paré G and

José C. Interventions for supporting nurse retention in rural and remote areas:

An umbrella reviews (2013) Hum Res Health 11: 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-11-44

Establishing a Rural School of Nursing in Lebanon: A Practical Model

Abstract

Full-Text

Background

Method

Discussion and

Conclusion

References