Research Article :

Single-blind, cluster randomized controlled trial

with 10 weeks, 6 month and 18 month follow-up. Community weight-loss programs

for children were randomized to (i) standard program plus incentive scheme

(intervention) or (ii) standard program alone (control). Primary outcome was

mean BMIz score at 18 months. Secondary outcomes included anthropometric and

behavioural measures. Results: A total of 37 sites (33 urban and 4 regional) and

512 children were recruited. Compared to baseline, at 18 month follow-up, the

total cohort achieved significant reductions in the mean BMIz score (1.7 v 1.0,

p<0.001), median screen time (16.5 v 15.8 hours/week p=0.0414), median

number of fast food meals per week (1.0 v 0.7, p<0.001) and significant

increases in physical activity (6.0 v 10.0 hours/week, p<0.001) and

self-esteem score (20.7 v 22.0, p<0.002). There were no significant

differences between the control and intervention groups at any follow-up

time-points. There were significantly more participants in the intervention

than control group who completed 10 sessions of the weight management program

(23% v 13%, p=0.015). Conclusions:

The incentive scheme, delivered in addition to the standard program, did not

have a significant impact on health outcomes in overweight children. However,

the intervention increased program attendance and overall cohort achieved

sustained improvements in clinical and lifestyle outcomes. Introduction Community-based weight

management programs are an important response to address childhood overweight and obesity. The United Kingdom Mind Exercise Nutrition Do

it (UK MEND) program is an evidence based community-based child weight

management program with efficacy in weight outcomes [7,8]. The MEND trial

(n=117) demonstrated that the intervention group had a significantly reduced

waist and BMI measures as well as improvements in physical activity and

self-esteem [8]. Based on these findings and due to the growing burden of

childhood obesity in New South Wales (NSW, Australia), MEND was translated into

a community context by NSW Health in 2009. The program was named Go4Fun® and

has an emphasis on reaching disadvantaged communities and accordingly, low

socioeconomic and regional areas [9]. It is a community-based,

multidisciplinary family focused program that targets weight-related behaviors

and self-esteem of children aged 7 to 13 years who are overweight or obese and

their families [10]. The program is managed by the NSW Office of Preventive

Health with the Better Health Company being responsible for centralised service

provision and the NSW local health districts (LHDs) deliver the 10 week

program. While the Go4Fun® program has demonstrated short and medium term

health benefits for those who complete it, opportunities to improve retention

and completion, goal setting and outcomes and sustained outcomes after the

program have been identified and there is limited data pertaining to

sustainability [9]. An opportunity for

optimizing behavior change amongst children might be via the use of incentives.

There is mounting evidence in adults for the role of incentives in enhancing

health-related behavior change [11-13]. However there is a high level of heterogeneity

across study designs, incentive strategies and a lack of long-term follow up

have prevented firm conclusions on the most effective incentive strategy for

behavior change. Several uncontrolled studies, with short-term follow-up, found

positive results associated with incentivizing health behaviors in children [14-16]. Other small randomized trials have used

a combination of psychological strategies and low value incentives to encourage

behavior change in exercise behavior [17,18] and fruit and vegetable

consumption [19,20]. These findings suggest that the use of extrinsic rewards

or incentives may have potential but to date this is a relatively unexplored

strategy. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the effectiveness of a

structured goal setting incentive scheme on health outcomes in overweight

children for 18 months. Materials and Methods Study design Single-blind, pragmatic

cluster RCT within the context of the existing 10 week Go4Fun® program with end

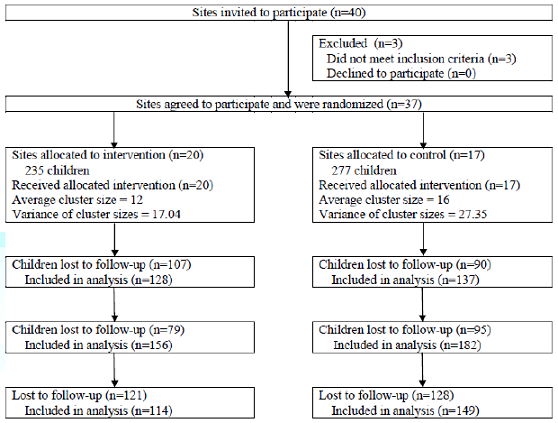

of program (10 weeks), 6 and 18 month follow-up (Figure 1).

Community weight-loss programs (sites) for children were randomized to either the (i)

standard program plus an enhanced goal setting and structured incentive scheme

(intervention) or (ii) standard program alone (control). Detailed methods are

described elsewhere [21]. The original protocol was to collect outcomes at

10-week and 6 months and 12-months, however, for financial and logistical

reasons data was collected at baseline, 10 weeks, 6 months and 18 months. The Consolidated

Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statements for cluster randomized

controlled trials (RCTs) [22] and for non-pharmacological interventions [23]

were followed and the trial registered (ACTRN12615000558527). Ethics approval

was obtained from the Sydney South Western LHD Research and Ethics Office

(HREC/13/LPOOL/157). Written informed consent was obtained from the

parent/guardian for each child. Eligibility/Recruitment Participants: Children were eligible to attend according

to the following criteria; (i) aged 7 to 13 years, (ii) body mass index >

85th percentile for their age and gender25 (iii) enrolled in and meet the

criteria to participate in Go4Fun® program at a participating site and (iv)

parent/guardian provide written and informed consent. Randomization Eligible sites were

randomized to either deliver the intervention (standard Go4Fun® plus incentives)

or control (standard Go4Fun® alone) program for 10 weeks. Randomization was

conducted using a computer generated sequence (1:1) with stratification

according to LHD to ensure equal representation across the various areas of NSW

between groups. The allocation sequence was concealed from the study personnel.

Although individual participants were not blinded to their group allocation, to

minimize bias participants were instructed not to reveal their group allocation

to the blinded outcome assessors during the follow-up assessments. Control sites Sites randomly allocated

to the control arm continued to deliver the standard and well-established

Go4Fun® program. The standard program is delivered by trained health

professionals and consists of weekly face-to-face group sessions (one per week)

for 10 weeks during the school term. Exercise sessions involve one hour of

activities that progressively develop strength, fitness and self-esteem [9].

Nutrition sessions include healthy eating advice, food label reading and

recipes [9]. Behavior change sessions include goal setting, problem solving and

role modeling [9]. Through preliminary focus groups consensus was reached to

ensure standardization of Go4Fun® between sites. It was also agreed that all

children could receive a water bottle (contingent on attending one session),

bouncy balls (three sessions) and skipping ropes (10 sessions). Intervention sites Sites randomly allocated

to the intervention arm delivered the standard Go4Fun® program plus the

enhanced goal setting and structured incentive scheme. The incentive scheme was

developed via an iterative process combining literature review, focus groups

and consensus meetings with stakeholders, building on the existing goal-setting

approaches [21]. At the intervention sites participating children participated

in an enhanced goal setting component and received standardized incentives for

reaching certain levels of goal attainment. That is, for the intervention,

participants set Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant and Timely (SMART)

[24] behavioral goals and achieving these goals resulted in the incentive being

provided. This approach emphasized the importance of enhancing the goal setting

process, including resetting/stretching them if they were achieved too easily,

in the program as well as linking goal achievement to incentives [24]. The goal

setting component and incentive scheme were developed and agreed upon during

the preliminary work for this study with an overview of the goal setting

enhancement and incentives being as follows. Goal setting: At the third session in the program

children and their parent/guardian in the intervention group were provided with

an enhanced resource (handout and poster) to guide them through jointly setting

an exercise and a nutrition goal (child and parent/guardian in collaboration).

Examples included I will play soccer for 30 minutes on three days a week at the

park with dad and I will try a new vegetable two times a week for dinner on

Wednesday and Sunday nights. Goal attainment

incentives: Children received

milestone based incentives for achieving their set goals. There were three

levels as follows: (i) vegetable slicer once two exercise and two nutrition

goals were achieved; (ii) sports store voucher (value $AU10) once four exercise

and four nutrition goals were achieved and (iii) height adjustable tennis set

(value of $AU20) once six exercise and six nutrition goals were achieved. In

addition, Go4Fun® leaders prompted participating children on a weekly basis to

review and reset their goals as needed. Goal attainment

reminders via text message and lottery style incentive: At session 9 of the 10 week program,

children and parents in the intervention group were encouraged to set goals to

be achieved after the program finished and parents/ guardians received weekly

mobile phone text message reminders to support and encourage children to

achieve their goals (and set new ones where relevant). Parents/guardians were

encouraged to text back with goal achievements that were rewarded with a ticket

entry (maximum of 8 tickets/month) into a site-wide prize draw for a family

pass to a local zoo that was drawn at six months. Outcomes The primary outcome was

mean difference in BMIz scores between control and intervention groups at 6 and

18 month follow-up. BMIz scores indicate how many units (of the standard

deviation) a childs BMI is above or below the average BMI value for their age

and sex. BMIz scores were calculated from raw BMI measures using the Centers

for Disease Control

growth reference data [26]. Secondary outcomes included anthropometric measures

(body weight, waist circumference) assessed according to standardized

procedures [27] and behavioral and self-esteem detailed below. Similar to BMIz

scores, waist measures in centimeters were converted to a waist circumference z

score based on reference data [26]. An adapted version of

the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale was used to assess self-esteem measures of the

participant children because this scale has been tested for reliability and

validity in numerous different languages [28]. The Rosenberg Self Esteem Scale

is a 10-item scale that measures global self-worth by measuring both positive

and negative feelings about the self with items answered using a 4-point scale

format [28]. The scale is scored by reversing 5 items and summing the scores

with higher scores representing higher self-esteem and there is a maximum score

of 40.28 The Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale (PACES) [29] was used to assess

physical activity and this tool has been found to have good internal consistency,

item-total correlations and validity in primary school children [29]. The full PACES

score was only able to be collected at 18 months due to program time

constraints at the earlier time-points. For nutrition assessment, relevant

questions were selected from the NSW Centre for Public Health Nutrition recommendations for nutrition questions [30]. The proportion of

participants achieving the Australian guidelines [31,32] for physical activity

(>60 minutes/day), screen time (<2 hours/day), fruit (2 serves/day) and

vegetable (5 serves/day) consumption were also analyzed. Data collection process Data were collected for

as many consenting participants at baseline, end of program, six and 18 months

by research assistants blinded to site allocation. Research staff conducting

the assessments was trained in measuring anthropometric measures including

height, weight and waist circumference, using standardized procedures [27].

Participants were contacted by blinded research assistants to attend the

follow-up sessions and data were entered into a secure online database.

Wherever possible face-to-face assessments were conducted, either in a local

community center or in the participants home. Where this was not possible data

was collected via a telephone call. Statistical

considerations For sample size

estimations, intra class correlation was calculated based on preliminary data

(214 individuals) across the recruited 40 sites and was found to be 0.16 for

BMIz score. To detect a between group difference of 0.24 (±0.43) in BMIz score

(based on outcome data from a previous Australian RCT examining 12 month weight

loss outcomes in children) [33]. 12 participants from each of the 40 sites (20

interventions, 20 controls) were required to achieve 80% power based on an

alpha of 0.05. Analysis was conducted

at the individual level and followed the intention-to-treat principle. The

control and intervention groups were compared on baseline characteristics,

program attendance and response to the self-esteem and the physical activity enjoyment questions. Continuous variables were reported in

means and Standard Deviations (SD) for normally distributed variables, and

median and Inter Quartile Intervals (IQI) for skewed variables. Categorical

variables were reported in number and percentages. For uni-variable

comparison, unadjusted regression within the framework of Generalized

Estimating Equation (GEE) for continuous variables and Rao-Scott chi-square

test for categorical variables were used to account for the clustering effect

of the sites. The outcomes were compared between the time points (baseline, 10

weeks, 6 months and 18 months) to see the effect of the Go4Fun® program across

time. Test for trend was performed for normally distributed continuous and

binary outcomes. For normally distributed continuous outcomes, unadjusted

regression within the framework of GEE with time as a continuous variable was

used, and for the binary outcomes, Cochran-Armitage trend test was used. For the multivariable

analysis of the primary outcome, the adjusted regression within the framework

of GEE was used to compare the mean difference in BMIz score at 18 months

between control and intervention groups. This model was adjusted for the

baseline characteristics including age, gender, attendance of all 10 sessions,

indigenous status, highest education qualification of father, highest education

qualification of mother, sole parent household, self-esteem score and physical

activity ≥60 minutes per day. Sensitivity analysis was

performed by repeating the main analysis using multiple imputations to include

patients with missing outcome data. We assumed that the data were missing at

random [34], where the missing elements of the data can be predicted by

observed data. Thirty imputations were generated using the fully conditional

specification method [35]. General linear model and logistic regression model

were used for continuous and binary outcomes, respectively, within the framework

of GEE. SAS 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA) and statistical

significance of P <0.05 were used for all analyses. Results A total of 37 sites (33

urban and 4 regional) and 512 children were recruited for the study. The study

ran from February 2015 to February 2017. End of program (10 weeks) follow-up

assessments were conducted for 265/512 (52%) children, 6 month follow-up

assessments were conducted for 338/512 (66%) children and 18 month follow-up

was conducted for 263/512 (51%) children (Figure 1). At 6 month follow-up,

reasons for loss to follow-up included; being un-contactable (n=70), not

interested or too busy (n=59), family problems (n=18), away on holiday (n=9),

child unwilling to attend (n=10), illness (n=2), language barrier (n=1) and

other (n=5). At 18 month follow-up, reasons for loss to follow-up included;

being un-contactable (n=82), not interested or too busy (n=87), family problems

(n=17), away on holiday (n=6), child unwilling to attend (n=14), illness (n=2),

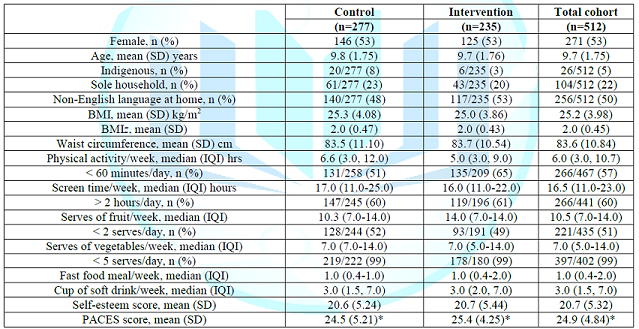

language barrier (n=2), other (n=39). Baseline and demographic data are

summarized in Table 1. The intervention and control Table 1: Baseline characteristics of the participating children Difference between

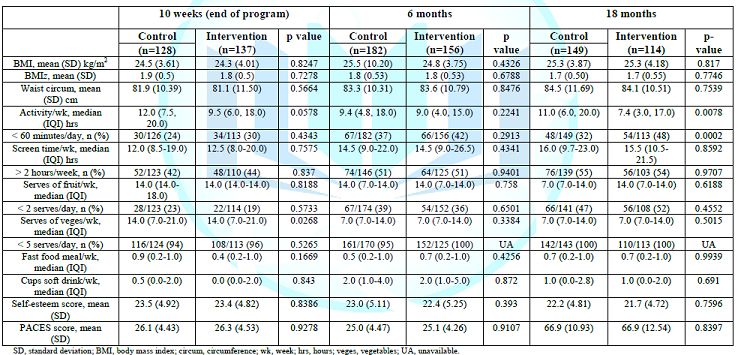

groups There was no significant

difference in any of the primary or secondary outcomes between the control and

intervention groups at 10 weeks, 6 months or 18 months (Table 3).

Further, after adjusting for the baseline demographic characteristics, the BMIz

scores at 18 months between the control and intervention groups remained

similar (p=0.704). Self-esteem and physical

activity enjoyment At baseline the majority

of children felt happy/satisfied with themselves (90%), felt they had a number

of good qualities (94%), felt participants were well

matched across age, gender, anthropometric and lifestyle measures (Table 1). Program

attendance The median number of

sessions attended by the total cohort was 7.5 (interquartile interval: 4.0,

9.0) out of a total of 10 possible sessions scheduled per week. Median number

of sessions attended after 10 weeks was significantly greater in the

intervention than control group (8.0 (4.0, 9.0) v 7.0 (4.0, 9.0)) sessions,

p=0.029). In the total cohort, 71% attended at least 5 (half) of the

program sessions but only 18% attended all 10 scheduled sessions. There were

significantly more participants in the intervention than control group who

participated in all 10 sessions (23% v 13%, p=0.015). Difference in overall

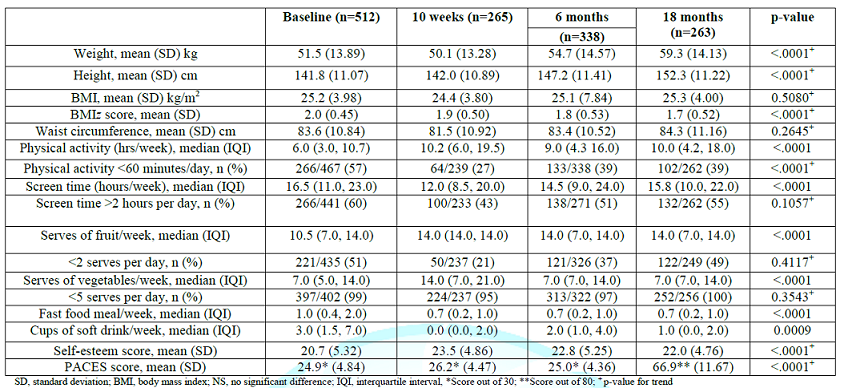

cohort over 18 months The total cohort

achieved a significant reduction in BMIz score from baseline to end of the

program and the improvement was maintained for 18 months (Table 2).

The total cohort also had significant reductions in screen time, number

of fast food meals

and cups of soft drink per week over the 18 months (Table 2).

Further, the total cohort achieved a significantly greater median hours

of physical activity per week, a significantly greater median serves of

vegetables per week, a significant improvement in the proportion achieved the

recommended level for physical activity and a significantly improved mean

self-esteem score over the 18 months (Table 2). they were able

to do things as well as most other children (88%), who did not feel useless

(58%), who felt that were as good as everyone else (80%), who did not feel like

a failure (73%) and who had a positive feeling about themselves (88%). Table

2:

Study outcomes for total cohort at 10 weeks, 6 months and 18 months In the total cohort, the

mean self-esteem score was 20.7 (±5.3) at baseline then increased to 23.5

(±4.9) at end of program and 22.8 (±5.3) at 6 months and was reduced slightly

at 18 months to 22.0(±4.8). However, there was no significant difference in

self-esteem score between the control and intervention groups at any of the

follow-up time-points (Table 3). For physical activity

enjoyment, only 6 questions were collected at baseline, end of program and 6

months and the full set of PACES questions was collected at 18 months. Of those

collected at baseline, the majority of children reported that they enjoyed

being active (94%), felt a sense of success with activity (91%) and felt good

when active (92%) while only the minority reported feeling frustrated when

active (25%) and disliking being active (14%). At 18 months, most children

reported that, when active, they enjoyed it (87%), found it pleasurable (85%),

felt energetic (74%) and that they got something out of it (85%). However,

there was a proportion that felt bored (22%), sad (6%), or and not interested

(11%) when active. Sensitivity analysis After imputing the

missing data using multiple imputations, the effect of the intervention on BMIz

at 18 month follow up was also not statistically significant (p=0.7932). Discussion In this pragmatic

cluster RCT, we found that enhancement and systematizing of an incentive

program to an existing community-based weight management program for children

did not significantly decrease BMIz scores in the intervention compared to the

control group. We did, however find

that the incentives program increased program attendance and that the overall

cohort achieved significant improvements in clinical and behavioral measures

over the 18 month period of the study. As is common in studies with this

population, we had high rates of loss to follow-up. Our results are similar

to others showing that it is difficult to achieve significant improvements in

BMI measures in children when comparing groups. Our study aligns with previous

individual RCTs of similar size showing no significant difference in BMIz

scores at follow-up in similar populations [36]. It is important to note that

while BMIz is an objective measure and is clinically significant and considers

growth rates of children, it was not initially intended to be an outcome

measure for clinical research and it may not be sensitive to change with

varying interventions [37]. However, it is

measurable in routine community settings and it does provide objective

information. Nonetheless, we did show an improvement in the overall cohort over

the 18 months of the study which is consistent with other Go4Fun research [38].

Similarly, a Cochrane review found reductions in BMIz score (between 0.17-0.24)

after one year of lifestyle intervention in children younger than 12 years are

possible [39]. As is common amongst studies recruiting children with health

conditions such as obesity, we found recruitment and retention a major

challenge in this research. The loss to follow-up was an issue despite

extensive efforts from our research team who are experienced with delivery of

childhood obesity programs and related research. Much effort was made to

contact all families using multiple means of contact, to offer home and phone

follow-ups but to do this within ethical constraints (for example, no more than

3 messages left on parents phones). These are almost always challenging for

weight management trials involving adults [40]. But are further inflated

for studies where the participants are young children and many were from

disadvantaged areas [41]. A previous study investigated quantitative and

qualitative reasons for lack of participation in research by children and the

results were complex and multifactorial with burden and unfamiliarity with

research being key outcomes [42]. Of course these challenges are much greater

when the study is examining obesity and targeting a population associated with

potential socioeconomic disadvantage [43]. Importantly, these are the

vulnerable populations and the current research aimed to tackle a highly sensitive

and challenging area of health. In addition, the challenges faced in terms of

follow-up are aligned with general retention in weight loss programs aimed at

children and perhaps are a symptom of the broader issue. Despite, the

challenges, it is important researchers continue to seek solutions for

addressing this major area of health. However, further health

services and qualitative research is needed to draw out themes and potential

solutions for others facing similar challenges. Larger studies are needed to

confirm the findings and generate more evidence in the area of behavior change

and overweight children. Our trial suggests that in this cohort the incentives

program did not significantly improve clinical or behavioral outcomes over 18

months. It is possible therefore that the extrinsic rewards are in themselves

not a solution for changing behavior in children. For complex

personal, emotional,

social and physical reasons it can be challenging to find factors that motivate

children who are overweight [44]. Some research suggests

that individual factors such as whether the child is introverted or extroverted

can be a factor that impacts on motivation to be physically active [44]. The

present study did not tailor the incentives or their delivery according to

individual child/family characteristics and hence this could be an area for

future research. The lack of a significant difference between

the groups but an overall cohort improvement may have indicated the

goal-setting [24,45]. In both groups was

successful and reduced differentiation between the groups. Further, it may also

have been the nature of the rewards themselves delivered in this current

program. Simple, inexpensive and healthy incentives were chosen and perhaps

these were not powerful enough to drive behavior change. Interestingly, the

family zoo passes were chosen based on a lottery system where those who

achieved more goals secured more tickets to enter and this reward was perhaps a

more powerful incentive. Future qualitative work will explore the perceived

value of individual rewards in the context of weight loss. Through this trial

several areas of potential program improvement were identified. They include

the need for revision of data collection questions and processes within

existing programs. This will improve the utility and efficiency of data

collection and ultimately contribute to improved performance and quality of the

program and its outcomes. The study also highlighted the importance of

benchmark reporting between sites to identify local and system level areas for

improvement. The study highlighted the importance of implementation of

strategies targeting reach and completion of weight management programs. This

is a common problem for initiatives but an area in need of continual quality

improvement and evaluation. The availability of healthy incentives for the

children and their families could offer one strategy for achieving this based

on our findings. The trial was pragmatic

and there were difficulties in recruiting children and minimizing loss to

follow-up that are not atypical of studies in this population. Our goal was to

be as integrated with the existing program as possible but this did mean we

were required to adapt to site-based procedures and therefore we were unable to

collect the full dataset for questionnaires such as PACES at baseline and end

of program. BMI, waist circumference and BMIz scores were used as a measure of

obesity rather than objective measurement of body composition for practical

data collection reasons. The pragmatic nature of the study meant that some

sites already had some simple incentives in place and this was difficult to

control although we are confident the impact of this was minimal. The strength

of the study was that local sites and families were involved in design of the

incentives and their implementation. Although we used healthy incentives such

as physical activity equipment and family outings, perhaps a different

incentives structure (e.g., where individual children could set their own

rewards) may have been more beneficial. The incentives intervention did improve

attendance at program sessions, but the study was not designed to increase

reach of the program and this is an area that requires further research. In

this study, we had original proposed doing final follow-up at 12 months but for

financial and logistical reasons this was extended to 18 months. Whilst not

ideal this change enabled slightly longer follow-up although ideally even

longer follow-up (e.g, 5-10 years) would be useful. Conclusions The incentive scheme, delivered

in addition to a standard weight-loss program in this trial, did not have a

significant impact on health outcomes in overweight children at 6 or 18 months.

Despite only about two-thirds of the total cohort attending more than half the

program sessions, the children in the total cohort had a variety of significant

improvements in clinical, lifestyle and self-esteem measures that were

maintained for 18 months. The incentives program

was associated with significantly greater attendance and completion of the

program. An important area of focus moving forward is to expand the reach of

community weight management programs so as to maximize the number of children who are able to

benefit. Further research could determine the impact of incentive schemes

amongst different cohorts and using a different structure of incentives that

are more sustained. Acknowledgements We would especially like

to thank Lily Henderson, Nicholas Petrunoff and Anita Crowlishaw for their help

throughout the design, implementation and evaluation of the trial. We would

like to thank Shirley Dang and Rory Gallagher for their involvement in the

design of the project and delivery of the incentives. We would also like to

thank Ewan Coates for his work on the preliminary analysis of the trial and

Michael Sanders from the Behavioral Insights Team for help with the power

analyses. The team wishes to thank all program leaders, participants, and their

families for contributing to and supporting this research. We are also thankful to

the Better Health Company and participating LHDs and their associated staff for

their contributions and support of the project. The NSW Health LHDs include Western

Sydney LHD, (Michelle Nolan, Deborah Benson Kristi Cunningham), Hunter New

England LHD (Silvia Ruano), North Sydney LHD (Sakara Branson), South East

Sydney LHD (Linda Trotter), and South Western Sydney LHD (Leah Choi, Stephanie

Baker, Kate Jesus). Trial registration

number: ACTRN12615000558527. Author

Disclosure Statement The Better Health

Company who are contracted by NSW Office of Preventive Health to provide

centralized services for the program were involved in development of the

incentive approach but were not part of the scientific team. The NSW Office of

Preventive Health support delivery of the Go4Fun® program across NSW. This work

is supported by National Heart Foundation of Australia pilot funding as part of

JRs Future Leader Fellowship, in-kind contributions from the Department of

Premier and Cabinet and The George Institute for Global Health. The NSW Office

of Preventive Health also provided financial support for the 18 month follow-up

to be completed. A the time of this work JR was funded by a Career Development

and Future Leader Fellowship co-funded by the National Health and Medical

Research Council and the National Heart Foundation (APP1061793). Authors Contributions JR, AG, SR conceived the

original concept of the study and the intervention. GE, SL supported details of

recruitment and data collection. KH and SK performed the sample size

calculations and will lead analysis of the results. JR and GE drafted the

protocol. GE, MAF, CIH, SL, CR, HYC and AG supported intervention development.

All authors contributed to the scientific design of the study and the protocol

development, are involved in the implementation of the project and have read

and approved the final manuscript. References 1.

World Health Organisation. Obesity and

Overweight: Fact Sheet No.311 2.

Singh AS, Mulder

C, Twisk JWR, Van Mechelen W and Chinapaw MJM. Tracking of childhood overweight

into adulthood: a systematic review of the literature (2008) Obesity Reviews9:

474–488. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00475.x 3.

Pandita A, Sharma

D, Pandita D, Pawar S, Tariq M et al. Childhood obesity: prevention is better

than cure (2016) Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 9:83–89. https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S90783 5.

Mead E, Brown T,

Rees K, Azevedo LB, Whittaker V et al. Diet, physical activity and behavioural

interventions for the treatment of overweight or obese children from the age of

6 to 11 years (2017) Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1-626. 6.

Biro FM and Wien

M. Childhood obesity and adult morbidities (2010) Am J Clin Nutrition

1499-1505. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2010.28701B 7.

Sacher PM, Chadwick

P, Wells JC, Williams JE, Cole TJ, et al. Assessing the acceptability and

feasibility of the MEND Programme in a small group of obese 7-11-year-old

children (2005) J Hum Nutr Diet 18: 3–5. 8.

Sacher P M,

Kolotourou K, Chadwick P M, Cole J T, Lawson M S et al. Randomized controlled

trial of the MEND program: a family-based intervention for childhood obesity

(2010) Obesity 18: 62–68. 9.

Welsby D, Nguyen

B, OHara BJ, Innes-Hughes C, Bauman A, et al. Process evaluation of an

up-scaled community based child obesity treatment program: NSW Go4Fun® (2014)

BMC Public Health 14: 7-140. 10. NSW

Office of Preventive Health. The first year in review, 2013. 11. Giles EL, Robalino S, McColl E, Sniehotta FF and Adams

J. The Effectiveness of Financial Incentives for Health Behaviour Change:

Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (2014) PLoS One 9: 90347. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0090347 12. Purnell JQ, Gernes R, Stein R, Sherraden MS and

Knoblock-Hahn A. A systematic review of financial incentives for dietary

behaviour change. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (2014) 114:

1023-1035. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2014.03.011 13. Strohacker K, Galarraga O and Williams DM. The Impact

of Incentives on Exercise Behavior: A Systematic Review of Randomized

Controlled Trials (2014) Ann Behav Med 48: 92-99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9577-4 14. Enright G and Redfern J. Summary of the evidence for

the role of incentives in health-related behavior change: Implications for

addressing childhood obesity (2016) Ann Pub Health Res 3: 1042-1047. 15. Just DR and Price J. Using Incentives to Encourage

Healthy Eating in Children (2013) J Human Resources 48: 855-872. 16. Loewenstein G, Price J and Volpp K. Habit formation in

children: Evidence from incentives for healthy eating (2015) J Health Economics

45: 47-54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2015.11.004 17. Hardman CA, Horne PJ and Lowe C. Effects of rewards,

peer-modelling and pedometer targets on childrens physical activity: a

school-based intervention study (2011) Psychol Health 26: 3-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440903318119 18. Horne PJ, Hardman CA, Lowe CF and Rowlands AV.

Increasing childrens physical activity: a peer modelling, rewards and

pedometer-based intervention (2007) Eur

J Clin Nutr 63: 191-198. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602915 19. Horne PJ, Tapper K, Lowe CF, Hardman CA, Jackson MC, et

al. Increasing childrens fruit and vegetable consumption: A peer modeling and

rewards-based intervention (2004) Eur J Clin Nutr 58: 1649-1660. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602024 20. Morrill BA, Madden GJ, Wengreen HJ, Fargo JD and

Aguilar SS. A Randomised Controlled Trial of the Food Dudes Program: Tangible

Rewards Are More Effective Than Social Rewards for Increasing Short- and

Long-Term Fruit and Vegetable Consumption (2015) J Acad Nutr Diet 116: 618-629.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2015.07.001 21. Redfern J, Enright G, Raadsma S, Allman-Farinelli M,

Innes-Hughes C, et al. Effectiveness of a behavioral incentive scheme linked to

goal achievement: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial (2016)

Trials 17: 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-016-1161-3 22. Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, and Altman GD.

Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials (2012) Br Med J

345: 5661. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.328.7441.702 23. Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF and Ravaud P.

Extending the CONSORT Statement to randomized trials of non-pharmacologic

treatment (2008) Ann Intern Med 148: 295-309. 24. Locke EA and Latham GP. A Theory of Goal Setting and

Task Performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA: Prentice-Hall. 25. Department of Health and Aging. About overweight and

obesity (2009) 26. Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM,

Guo SS, et al. CDC growth charts: US Advance data from vital and health

statistics (#314), Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics (2000) Adv

Data 314:1-27 27. Lohman TG, Roche AF and Martorell R. Anthropometric

Standardization Reference Manual (1988) Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, 55-80. 28. Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Self-image,

Princeton (1965) Princeton, University Press, New jersey, USA. 29. Moore JB, Yin Z

and Hanes J. Measuring Enjoyment of Physical Activity in Children: Validation

of the Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale (2009) J App Sport Psychol 21:

116-129. 30. Flood V, Webb K and Rangan A. Recommendations for short

questions to assess food consumption in children for the NSW Health Surveys

(2005) NSW Centre for Public Health Nutrition. 32. Department of Health (2013) Australian

dietary guidelines. Australian Government. 33. Golley RK, Magarey AM, Baur LA, Steinbeck KS and

Daniels LA. Twelve-month effectiveness of a parent-led family-focussed

weight-management program for children: a RCT (2007) Pediatrics 119: 517-524. 34. Seaman S, Galati J, Jackson D and Carlin J. What Is Meant

by “Missing at Random”? (2013) Stat Sci 28: 257-268. 35. Van Buuren S, Brand JPL, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CGM and

Rubin DB. Fully conditional specification in multivariate imputation (2006) J

Stat Comput Simul 76: 1049-1064. https://doi.org/10.1080/10629360600810434 36. Kelley GA, Kelley KS and Pate RR. Effects of exercise

on BMI z-score in overweight and obese children and adolescents: a systematic

review with meta-analysis (2014) BMC Pediatr 14: 225. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-14-225 37. Freedman DS, Butte NF, Taveras EM, Lundeen EA, Blanck

HM, et al. BMI z-Scores are a poor indicator of adiposity among 2- to

19-year-olds with very high BMIs, NHANES 1999-2000 to 2013-2014 (2017) Obesity

(Silver Spring) 25: 739-746. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.21782 38. Khanal S, Welsby D, Lloyd B, Innes-Hughes C, Lukeis S,

et al. Effectiveness of a once per week delivery of a family‐based childhood

obesity intervention: a cluster randomised controlled trial (2015) Paediatric

Obesity 11: 475-483. 39. Oude LH, Baur L, Jansen H, Shrewsbury VA, OMalley C, et

al. Interventions for treating obesity in children (2009) Cochrane Database

Syst Rev 001872. 40. Voils CI, Grubber JM, McVay MA, Olsen MK, Bolton J, et

al. Recruitment and Retention for a Weight Loss Maintenance Trial Involving

Weight Loss Prior to Randomization (2016) Obes Sci Pract 2: 355-365. 41. Berry DC, Neal M, Hall EG, McMurray RG, Schwartz TA, et

al. Recruitment and retention strategies for a community-based weight

management study for multi-ethnic elementary school children and their parents

(2013) Public Health Nurs 30: 80-86. 42. Hein IM, Troost PW, de Vries MC, Knibbe CA, van

Goudoever JB, et al. Why do children decide not to participate in clinical

research: a quantitative and qualitative study (2015) Pediatr Res 78: 103-108. 43. El-Sayed AM, Scarborough P and Galea S. Socioeconomic

inequalities in childhood obesity in the United Kingdom: a systematic review of

the literature (2012) Obesity Facts 5: 671-692. https://doi.org/10.1159/000343611 44. McWhorter JW, Wallmann HW and Alpert PT. The Obese

Child: Motivation as a Tool for Exercise (2003) J Pediatr Health Care 17:

11-17. https://doi.org/10.1067/mph.2003.25 Kivetz

R, Urminsky O and Zheng Y. The Goal-Gradient Hypothesis Resurrected: Purchase

Acceleration, Illusionary Goal Progress, and Customer Retention (2006) J

Marketing Res 43: 39-58. https://doi.org/10.1509%2Fjmkr.43.1.39 *Corresponding author Julie Redfern,

Professor, The University of Sydney at Westmead Hospital, Westmead, Australia,

Tel: +61-02- 8890-9214, E-mail: julie.redfern@sydney.edu.au Citation Redfern J, Enright G,

Hyun K, Raadsma S, Farinelli MA, et al (2019) Effectiveness of a behavioral

incentive scheme linked to goal achievement in overweight children: a cluster

randomized controlled trial, J Obesity and Diabetes 3: 1-9 Incentives, Children, Weight Loss, Nutrition,

Physical Activity, Community, Obesity, Cardiac, Prevention, TranslationEffectiveness of a Behavioral Incentive Scheme Linked to Goal Achievement in Overweight Children: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

Methods: Full-Text

The high prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity is a major public

health problem. It has implications for current and future health services,

both for weight management and treatment of associated co-morbidities. In 2016,

340 million children and adolescents (worldwide) were estimated to be

overweight or obese [1]. Most importantly, being overweight as a child increases the risk of obesity in adulthood and

accelerates the risks of associated and life-threatening conditions such as

cardiovascular disease [2,3]. The extent of the epidemic and its short and

long-term effects on physical and psychological health have made the prevention

and treatment of childhood overweight and obesity a high priority [4,5]. Public

health and community services are integral in preventing and managing childhood obesity [6] and strategies informing interventions for

health-related behavior change in children are becoming increasingly important.

Figure 1: Flow of sites and

participants through the incentives RCT

Sites: All Local Health

Districts (LHDs) across NSW, Australia where the standard Go4Fun® program was

delivered were invited to participate. To be eligible sites needed to (i) be

currently delivering the standard Go4Fun® program, (ii) have an enrolment

average of at least 10 children per site per term in the year prior to study

commencement and (iii) be willing to participate in the trial and adhere to

standardized procedures for duration of the trial.

Keywords