Research Article :

Emmanuel Andrès, Rachel Cottet Mourot, Olivier Keller, Khalid Serraj and Thomas Vogel Agranulocytosis is a life-threatening disorder in any age and

also in the elderly subjects who are receiving on the average a larger number of

drugs than younger subjects. This disorder frequently occurs as an adverse

reaction to drugs, particularly to antibiotics, antiplatelet agents,

antithyroid drugs, neuroleptics or anti-epileptic agents and nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory agents. Although patients experiencing drug-induced agranulocytosis

may initially be asymptomatic, the severity of the neutropenia usually translates

into the onset of severe sepsis that requires intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotherapy.

In this setting, hematopoietic growth factors have been shown to shorten the

duration of neutropenia. Thus with appropriate management, the mortality rate

of idiosyncratic drug-induced agranulocytosis is now of 5 to 10%. Today,

drug-induced agranulocytosis still remains a rare event with an annual

incidence from 3 to 12 cases per millions of people. However, given the

increased life expectancy and subsequent longer exposure to drugs, as well as

the development of new agents, physicians should be aware of this complication

and its management. Idiosyncratic drug-induced agranulocytosis, or

severe neutropenia, is characterized by: a neutrophil count under 0.5 x 109/L;

usually health impairment; and often severe infections such as pneumonia, septicemia

or septic shock, in case of natural evolution [1]. In the majority of cases, the

neutrophil count is under 0.1 x 109/L. All drugs may be causative but

clozapine, antithyroid drugs, sulphasalazine have been regularly incriminated

[2]. It is a relatively rare disorder, more frequently reported in elderly

patients who are receiving on the average a larger number of drugs than younger

subjects [1,3]. Because of the infections in often frailty patients, it is

associated with an estimated mortality rate of 5 to 20% [1]. In the present paper, we report and

discuss clinical particularities of idiosyncratic drug-induced agranulocytosis

or severe neutropenia in elderly patients, especially in the light of our own

experience. In Europe, the annual incidence of

symptomatic idiosyncratic drug-induced agranulocytosis is between 3.4 and 5.3

cases per million people per year [4]. In the USA, Strom et al. reported rates

ranging from 2.4 to 15.4 [5]. In our experience (1996- 2015), the annual

incidence of drug-induced agranulocytosis remains stable, with about 6 cases

per million people, despite the development of the pharmacovigilance [6].

This incidence increases with the age, as only 10% of cases are reported in

children and young adults and more than half of these episodes occur in people

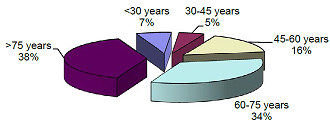

over 60 years old [1]. In a 91 patients cohort study followed in our hospital,

72% of patients were aged 60 years or more, 38% were 75 years old or older

(Figure 1) [6]. The higher incidence of agranulocytosis in elderly patient was

also demonstrated by the International Agranulocytosis and Aplastic Anemia

Study, the most important prospective study of the incidence of agranulocytosis

in Europe [7]. Agranulocytosis is about twice as frequent among women as men,

but this rate is likely to be a biased because of the longer life expectancy in

women, with a possible longer period of exposure to drugs [1]. All drugs may be causative of severe

neutropenia or agranulocytosis [1,2,8]. However for the majority of these compounds,

the risk seems to be very small. For drugs such as clozapine, sulphasalazine, antithyroid drugs,

ticlopidine, gold salts, penicillamine and phenylbutazone, it may be higher

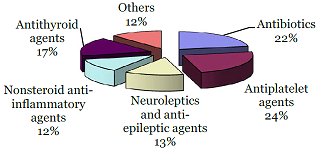

[8]. In our experience, the most frequent causative types of drug were:

antibiotics, particularly beta-lactam and trimetoprim sulfamethoxazole

(>20%); antiplatelet agents such as ticlopidine (>20%); antithyroid drugs

(>10%); neuroleptic and anti-epileptic agents (>10%); and nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatory agents (>10%) [6]. Figure 2 includes all types of drugs

involved in patients aged 65 years or more [3,6]. This is usually the same

drugs as those implicated in adults, except perhaps for antithyroid drugs. In

the aforementioned cohort, two-thirds of the patients received more than 2

drugs, with a mean of 3 drugs, accounting for the difficulty in relating the

agranulocytosis to its causative agent [3,6]. This is particularly the case in

the elderly, polymedicated, fragile, with often self-medication and cognitive

impairment making the drug investigation difficult or impossible. In the

literature, consensual criteria to establish the diagnosis of idiosyncratic

drug-induced agranulocytosis has been described [9]. For a few drugs, specific

risk factors have been identified such as histocompatiblity antigens (HLA): HLA

B27 and levamizole, HLAB38 and clozapine [1,10]. Other risk factors include underlying

autoimmune diseases,

renal failure or concomitant treatment with probenecide [10]. Patients with idiopathic

drug-induced agranulocytosis or deep neutropenia usually present, at diagnosis

or during their follow-up: high fever, sore throat, stomatitis, diarrhea and a general

sensation of malaise,

including headache, chills, myalgia and/or arthralgia [1,2,11]. Most patients develop septicemia and

some have evidence of severe pneumonia as well as anorectal, skin or oropharyngeal

infection and septic

shock [1,2]. This is particularly the case in elderly patients with several

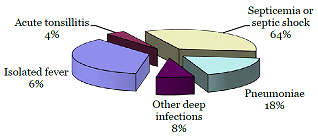

comorbidities and fragile underlying [3]. In our cohort study, clinical

features included isolated fever in about 40% of the cases, septicemia and septic

shock in 35% and documented infection in 25%, with pneumonia in 10%, sore

throat and acute tonsillitis in 7% or others in 8% [6]. It is noteworthy that in

elderly patients clinical manifestations were commonly severe with at least

two-thirds of septicemia or septic shock (Figure 3) [3]. However, some patients

remained at least transiently asymptomatic (in the beginning of the

agranulocytosis), supporting the close monitoring of blood count in individuals

receiving high risk medication

such as antithyroid drugs or ticlopidine [1,2]; a small number of these

hospitalized elderly patients (<2%) remains asymptomatic. Besides a granulocyte blood count

below 0.5 x 109/L,

the hemoglobin and platelets counts are commonly normal [1,2]. However in

elderly patients, associated hematological abnormalities are frequent: anemia in at least 20

to 30% of cases, thrombocytopenia in 10% [ 6 ]. Thus in these elderly patients,

bone marrow examination is routinely required to exclude an underlying

pathology [1]. For several authors [12], bone marrow examination is also required

to predict the duration of the neutropenia. The bone marrow typically shows a

normal or mildly reduced total cellularity contrasting with the absence of

myeloid precursor cells (“hypo- cellularity”) [1]. In some cases, the lack of

any mature myeloid cells is observed, whereas immature forms to the myelocyte

stage remain preserved (“myeloid blocking”) [1]. In the case of a lack of myeloid

precursors, blood count recovery is unlikely before 14 days [12]. The picture

of myeloid blocking is associated with a recovery within 2 to 7 days. Differential diagnosis of

idiosyncratic drug-induced agranulocytosis or severe neutropenia is often not

easy in elderly patients. In fact, in this population, various miscellaneous conditions

can induce absolute neutropenia [1,3]. The most relevant differential diagnoses

include: (i) nutritional deficiencies (cobalamin and folate deficiencies); (ii)

neutropenia appearing as the first manifestation of a bone marrow failure such

as myelodysplastic syndromes; (iii) neutropenia secondary to severe sepsis

immune (especially viral); or (iv) neutropenia associated with hypersplenism [1]. Other differential diagnoses rarely

include, in elderlies, neutropenia secondary to the peripheral destruction of polymorphonuclear

cells such as Feltys

syndrome or systemic lupus erythematosus (that is also often drug

associated) [1]. Until the last decade, the mortality rate for idiosyncratic

drug- induced agranulocytosis was 10 to 16% in European studies [1,2], but it

has recently dropped to less than 10% (<5% in our cohort study [6]),

probably due to the improvements in management and treatment of this condition

[1,2,13]. The highest mortality rate is

observed in older patients, as well as in those experiencing renal failure,

bacteremia or shock at diagnosis [1,12]. We have partially confirmed these data

in a uni- and multivariate analysis of factors affecting outcome in our cohort

study (n = 91 patients) [14]. Table 1 presents the data of the multivariate analysis.

They showed that neutrophil

count under 0.1 x 10 9 /L

at diagnosis, septicemia and/or shock were variables significantly associated

with a longer time to neutrophil recovery. In contrast, use of hematopoietic

growth factors is associated with a shorter time to neutrophil recovery in our

experience ( see below ). Remarkably in our study, age is not

a prognostic factor [14], despite the severity of the clinical manifestations

of agranulocytosis in elderly patients. The management of idiosyncratic

drug-induced agranulocytosis or severe neutropenia begins with the immediate

withdrawal of any potentially causative drug [1,2]. In elderly patients, the

patients medication history must be carefully (because of poly- and

self-medication) and chronologically obtained in order to focus on the

suspected agent(s) [1]. Declaration of this side-effect in the pharmacovigilance authorities

must always be carried. In our opinion, even for drugs with

a known but rare association with agranulocytosis the rarity and

unpredictability of the reaction makes regular routine monitoring not

worthwhile [1]. However, in some high-risk drugs for agranulocytosis such as

clozapine or ticlopidine or antithyroid drugs routine monitoring is required

[15]. Measures to be undertaken concomitantly include the aggressive treatment

of any diagnosed sepsis as well as the prevention of secondary infections

[1,2]. Preventive measures require good

hygiene maintenance with special attention to high-risk areas such as the

mouth, skin and perineum [1]. Patient isolation and empirical prophylactic

antibiotherapy ( e.g. digestive decontamination) have been proposed, but

their usefulness in limiting the infectious risk is far from validated [1]. In case of febrile neutropenia,

bacteriological documentation is warranted [1]. The finding of a causative

pathogen may be unsuccessful and, as in our cohort study, is typically achieved

in only around 30% of the cases, consisting mainly of Gram-negative bacilli and

Gram-positive cocci (mostly Staphylococcus sp ) [6]. The occurrence of sepsis in this

life-threatening disorder, in a frailty population of patients, requires prompt

management, including intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, after blood,

urine and any other relevant samples have been cultured [1-3]. Empirical

broad-spectrum antibiotherapy is generally the best choice, but may be adapted,

depending on the nature of the sepsis, the clinical status of the patient and

local patterns of antibiotic resistance [1]. When an antibiotic is suspected of

having induced the agranulocytosis, one should keep in mind potential antibody

cross- reactivity, and choose the antibiotics to be

administered carefully. In our hospital, we commonly combine

cephalosporins such as cefotaxime or ceftriaxone with aminoglycosides [1,6]. Alternatively

to cephalosporins, the use of piperacillin/tazobactam or even imipenem may be

considered in certain situations. Therapeutic measures such as transfusions of

granulocyte concentrates should only be used in exceptional circumstances, and

only for the control of life-threatening antibiotic-resistant infections such

as perineal gangrene [1]. In this setting, the usefulness of

hematopoietic growth factors has been previously reported [2,16-18]. In our

experience, G-CSF or GM-CSF (at a mean dose of 300 μg per day) were found

useful in drug-induced agranulocytosis, especially in elderly patients, in shortening

the duration to blood count recovery without major toxicity or side

effects [18]. In a non-randomized cohort study of 54 elderly patients (>65 years),

we have previously shown that G-CSF use was safe and led to a significant reduction

in the mean duration to hematological recovery: 5 days versus 10 days for neutrophil

count to be >1.5 x 10 9 /L [19]. The duration of antibiotic therapy and

hospitalization, in addition to the global cost of agranulocytosis management,

was also reduced. More recently, in a multivariate analysis

of all our drug- induced agranulocytosis patients (n = 91), we have

demonstrated that G-CSF was an independent variable positively affecting the duration

to hematological recovery [14]. In elderly patients, idiosyncratic

drug-induced agranulocytosis or deep neutropenia is typically a serious accident

due to the frequency of severe sepsis (such as deep infections, septicemia and

septic shock), but modern management with broad-spectrum antibiotics and

hematopoietic growth factors, is likely to improve the prognosis. Given the increased life expectancy and

subsequent longer exposure to drugs, as well as the development of new agents, physicians should be

aware of this complication and its management. In all cases, an exhaustive

pharmacovigilance investigation must be made. Declaration of this side-effect in the pharmacovigilance

authorities must also always be carried. 1. Andrès E, Zimmer J, Mecili M,

Weitten T, Alt M. Clinical presentation and management of drug-induced

agranulocytosis (2011) Expert Rev Hematol 4:143-151. Emmanuel Andrès, Service de Médecine Interne, Diabète et Maladies métaboliques, Clinique Médicale B, Hôpital Civil, Hôpitaux Universitaires de Strasbourg, 1 Porte de l’Hôpital, 67 091 Strasbourg Cedex, France, Tel: 33-(3)-88-11-50-66; Fax: 33-(3)-88-11-62-62 E-mail: emmanuel.andres@chru-strasbourg.fr Andrès E, Mourot RC, Keller O, Serraj K, Vogel T (2015) Clinical Particularities of Drug-Induced Agranulocytosis or Severe Neutropenia in Elderly Patients. PAP 101:1-4Clinical Particularities of Drug-Induced Agranulocytosis or Severe Neutropenia in Elderly Patients

Abstract

Full-Text

Introduction

Incidence in elderlies

Drugs involved in elderlies

Clinical manifestations in elderlies

Differential diagnosis in elderlies

Prognosis and Mortality Rate

Management in Elderlies

Conclusions

References

2. Andersohn F, Konzen C, Garbe E. Systematic

review: agranulocytosis induced by nonchemotherapy drugs (2007) Ann Intern Med

146:657-665.

3. Kurtz JE, Andrès E, Maloisel F,

Kurtz-Illig V, Heitz D, et al. Drug-induced agranulocytosis in elderly. A case

series of 25 patients (1999) Age Aging. 28:325-326.

4. Strom BL, Carson JL, Schinnar R, Snyder

ES, Shaw M. Descriptive epidemiology of agranulocytosis (1992) Arch Intern Med

152:1475-1480.

5. Van der Klauw MM, Goudsmit R,

Halie MR, vant Veer MB, Herings RM, et al. A population-based case-cohort study

of drug-associated agranulocytosis (1999) Arch Intern Med 159:369-374.

6. Andrès E, Maloisel F, Kurtz JE, Kaltenbach

G, Alt M, et al. Modern management of non-chemotherapy drug-induced agranul ocytosis:

a onocentric cohort study of 90 cases and review of the literature (2002) Eur J

Intern Med 13:324-328.

7. Kelly JP, Kaufman DW, Shapiro S.

Risks of agranulocytosis and aplastic anemia in relation to the use of cardiovascular

drugs: The International Agranulocytosis and Aplastic Anemia Study (1991) Clin Pharmacol

Ther 49:330-341.

8. Van der Klauw MM, Wilson JH,

Stricker BH. Drug-associated agranulocytosis: 20 years of reporting in the

Netherlands (1974-1994) (1998) Am J Hematol 57:206-211.

9. Bénichou C, Solal-Celigny P. Standardization

of definitions and criteria for causality assessment of adverse drug reactions.

Drug-induced blood cytopenias: report of an international consensus meeting

(1993) Nouv Rev Fr Hematol 33:257-262.

10. Young NS. Drug-related blood dyscrasias

(1996) Eur J Haematol 60 (suppl):6-8.

11. Patton WN, Duffull SB. Idiosyncratic

drug-induced haematological abnormalities: incidence, pathogenosis, management and

avoidance (1994) Drug Safety 11:445-462.

12. Julia A, Olona M, Bueno J, Revilla

E, Rosselo J, et al. Drug-induced agranulocytosis: prognostic factors in a

series of 168 episodes (1991) Br J Hematol 79:366-372 .

13. Vial T, Pofilet C, Pham E, Payen

C, Evreux JC. Agranulocytoses aiguës médicamenteuses: expérience du Centre

Régional de Pharmacovigilance de Lyon sur 7 ans (1996) Therapie 51: 508-515. *Corresponding author

Citation

Keywords