Research Article :

Background: Clear clinical communication between clinicians and radiographers in

confirming of clinical information remains key in the provision of quality

healthcare. As per procedure, clinicians make a clinical diagnosis and

thereafter, request the radiographers to carry out sonographic examinations and

produce Diagnostic Ultrasound Reports (DURs) based on the clinicians request.

Therefore, this study aimed at assessing the adequacy of clinical communication

between clinicians and radiographers on the quality of DURs at the University

Teaching Hospital (UTH) in Lusaka, Zambia. Methods: A cross-sectional

descriptive study design was used. A total of 40 Clinicians were conveniently

recruited into the study while 12 radiographers were purposefully sampled. Two

types of special semi-structured, self-administered questionnaires were

administered. Each type was to a specific professional discipline, i.e.

clinicians or radiographers. Data analysis was done using Social Statistical

Packages for Social Scientist Version 22. Results: The study revealed

that it was a common practice for the radiographers to receive requests from

the clinicians demanding for repeat of the DURs. Clinical meetings between

clinicians and radiographers were irregularly held. Less than a quarter of the

clinicians lacked specialized training in Diagnostic Ultrasound. The study

further revealed that practitioners gender had no effect on the adequacy of

communication between clinicians and radiographers while qualifications and

work experience had effect. Conclusion: The study showed that communication

between clinicians and radiographers at the UTH was inadequate. The major

causes to this inadequacy included the use of unstandardized radiological

request forms and lack of regular clinical meetings.

A Diagnostic Ultrasound Report

(DUR) is a leading method of communication from the radiographer to the

clinician in order to provide feedback on the requested ultrasound

examination/s.1 This feedback is important in the

provision of quality healthcare delivery. Therefore, any inadequacies in the

communication between the clinicians and the

radiographers on DUR can compromise the clinicians diagnosis, and may as well

lead to wastage of resources in the radiological department. The growth in the use of ultrasound as a diagnostic imaging

tool has led to the high demand for a workforce with appropriate competencies

to perform and interpret diagnostic ultrasound imaging. According to

Makanjee et al, diagnostic ultrasound imaging is a dominant first-line

investigation for a variety of abdominal symptoms because of its applicability

and comparative accessibility in most healthcare institutions.2 Diagnostic ultrasound imaging success in terms of diagnosis,

however, depends upon numerous factors, the most important of which is the

competency of the operating practitioner. Other factors include the status of

equipment and the body stature of the patient. Diagnostic ultrasound imaging is considered to be safe, effective, and highly

adaptable to varied clinical needs and settings. This diagnostic imaging

modality is capable of providing clinically relevant information about most

internal parts of the body cost-effectively. Obtaining maximum clinical benefit

from diagnostic ultrasound, as well as ensuring the optimal utilization of

healthcare resources, requires a combination of appropriate ultrasound

diagnostic equipment and competencies in the performance and interpretation of

the ultrasound examinations.4 Diagnostic

reporting is inseparable from sonographic imaging,

as a means of communication from the radiographers to the referring clinicians. Clinicians

generally do not have direct contact with radiographers to discuss and clarify

ultra-sonographic findings. Therefore radiographers are expected to provide

clinicians with duly detailed diagnostic ultrasound reports as feedback to the

clinicians clinical question/s. Based

on anecdotal information, the returned DURs as feedback from clinicians to the

radiographer in relation to the inadequacies of DURs, clinicians especially

from Internal medicine, general surgery, pediatrics, obstetrics

and gynaecology

raise concerns over the quality of the DURs or radiographers competencies.6 The

radiographers equally try to shift the blame to the inadequacies in the

radiological requests from the clinicians. The clinicians concerns are

sometimes viewed as in conflict with the scope of ultrasonography. Yet the

overall inadequacies could result into clinicians receiving questionable

results, which in turn would negatively affect conclusive decisions on the

management of patients.6,7, 8 As a result, clinicians have excessively gone for

second opinions. Such approach contributed to delays and increased cost in the

patients clinical management. Studies

have been conducted and documented in different countries such as the United

Kingdom, India, Uganda and Ghana, assessing clinical communication between

clinicians and radiographers and effect on the quality of diagnostic ultrasound

reports.5, 9, 10 There has been no known documented study in Zambia or

neighboring countries in this regard. It is envisaged that this study would

provide useful information for promoting the quality of Diagnostic Ultrasound

Imaging and Reporting by radiographers in Zambia and other comparable

healthcare settings. A

cross-sectional descriptive study design was used in the study. The study was

conducted at the University Teaching Hospital in Lusaka, which is the highest

referral hospital in Zambia. Collectively 30 clinicians from the departments of

Internal Medicine, General Surgery, Pediatrics, Obstetrics and Gynecology were

conveniently sampled; and 12 radiographers who carry out sonographic

examinations in the UTH Radiology Department were purposively recruited into

the study. Convenience

sampling methods were used to select the study participants. Using EPI Info 7,

from a collective total of 150 clinicians serving the Departments of Internal

Medicine, General Surgery,

Paediatrics, Obstetrics

and Gynaecology, a sample size of 40 clinicians was generated. A

self-administered, semi-structured, questionnaire was administered to each of

the clinicians recruited in the study. All the 12 radiographers practicing

ultrasonography in the UTH Radiology Department were included in the study.

Each of these radiographers was as well given a semi-structured questionnaire

specifically suited to them for self-administration, in line with the themes in

the clinicians questionnaires. All

the 40 clinicians included in the study had earlier requested for

ultrasonography with DURs from the radiographers. Despite serving in the

mentioned Departments, a clinician without history of requesting for a DUR was

excluded from the study. The radiographers included in the study were on

full-time employment and performed ultrasonography in the UTH Radiology

Department. The student radiographers

and qualified radiographers that did not perform sonographic examinations were

not included in the study. Statistical

Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 22 software was used in data

analysis. Microsoft Excel 2007 was used to generate figures and tables. Ethical

clearance was obtained from the Lusaka Apex Medical University Ethics

Committee, and permission to proceed with the study was granted by the UTH

Management. There were no foreseen risks or harm to the participants and UTH as

an institution. Participation in the study was voluntary. The consent was

obtained from the participants prior to issuing them with questionnaires by

endorsing the consent form adjoining the information sheet. A

total of 52 questionnaires were administered to the study participants of which

40 were clinicians and 12 were radiographers, which entailed the distribution

of participants between clinicians and radiographers: 40 of 52 (77%) and 12of

52 (23%) respectively. With regard to data realization, 30 (75%) duly completed

questionnaires were obtained from the clinician-participants while 10 (83.3%)

were obtained from the radiographers. This attainment represented collective

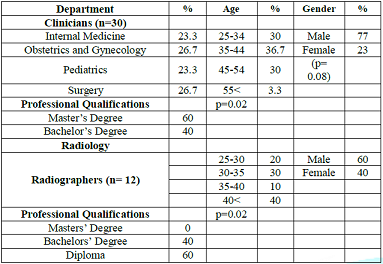

realization of 77% response rate. Socio-demographic

Profiles of the Participants The

participants in this study belonged to two professional disciplines: clinicians

and radiographers. The clinician-participants departmental affiliations were:

26.7% Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 26.7% Internal Medicine, 23.3% Surgery and

23.3% Paediatrics. The majority of the clinician-participants (77%) were males,

while 23% were females. In terms of age, the majority (36.7%) of the

clinician-participants were of 35- 44 years age group. The oldest (3.3%)

clinician-participant was older than 55 years. With respect to professional

qualifications, most clinician-participants (60%) held Masters degree as

highest qualification in respective areas of specializations compatible with

the affiliation departments (Table 1). The radiographers

constituted 10 of 40 (25%) realized participation, out of which 60% of them

were males and 40% were females. Most (40%) of the radiographer-participants

were older than 40 years, while the youngest age group (20-25 years old)

constituted 20% as in Table 1. Table 1: Socio-demographic Profiles of the Participants Work

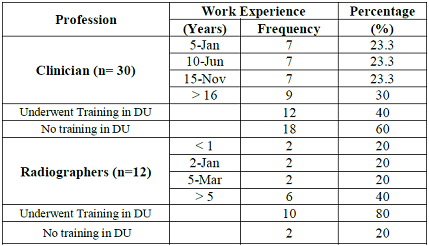

Experience and Competency of Clinicians and Radiographers at the UTH The

study showed that at least 30% of the clinician-participants at UTH had the

longest work experience of at least 16 years. The shortest work experience

among the clinicians was one to five years, and constituted 23.3% of the

clinician-participants. The majority (60%) of the clinicians did not have

formal qualifications in Diagnostic Ultrasound (DU) although 40% of the

clinicians had history of short in-house training in DU. In-house training

involved workshops (20%) and specific modular trainings (10%). Furthermore,

some clinicians (6.7%) undertook short courses and others (3.3%) pursued

diploma training in DU (Table 2). The

findings indicate that 40% of the radiographers had more than 5 years of work

experience as ultrasonographers while the other (60%) radiographers had work

experiences ranging from less than one year to five years. The study further showed that the majority (80%) of

the radiographers practicing ultrasonography at the UTH had formal training in

DU at diploma qualification (70%) with one (10%) holding Bachelors degree in

Sonography. There were 20% of the radiographers who obtained competencies

through in-house training (Table 2). Use

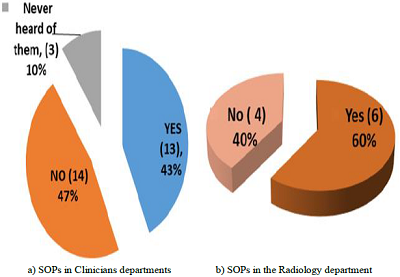

of DU Standard Operating Procedures by Clinicians and Radiographers On

the presence and use of Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) between clinicians

and radiographers, 47% of the clinicians stated that SOPs were never in

existence in their Departments while 43% of the clinicians indicated that they

had SOPs, whereas 10% of the clinicians indicated that they had never heard of these

procedures during their years of practice. Out of the 43% clinicians with SOPs

in their departments, the majority (69.2%) of them reported that they always

requested DU examinations according to the SOPs, whereas 23.1% indicated that

they occasionally followed SOPs in requesting for DU examinations. However,

7.7% of the clinician-participants indicated that they never followed the SOPs.

Table 2: Work Experience and Competencies of Clinicians and Radiographers. There

were 60% of the radiographer-participants indicating that they had SOPs for DU

examinations, whereas 40% of the radiographers reported that they did not have

the SOPs. Among the radiographers that indicated presence of the SOPs, 83% of

them reported that the SOPs were not displayed in their ultrasound rooms,

though 17% of the radiographers indicated that the SOPs were readily available

in the operating rooms. Among 60% of the radiographers that indicated

availability of SOPs, the majority (83.3%) indicated that they followed the

SOPs of sonographic reporting, while 16.7% of the radiographers indicated that

they never followed the SOPs of sonographic reporting. The latter reaffirmed

that they did not follow the standard way of writing the reports, but used

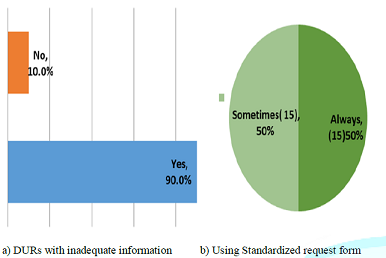

their own improvised formats of reporting. Quality

of Clinical and Diagnostic Information on the Generated Sonographic Requests

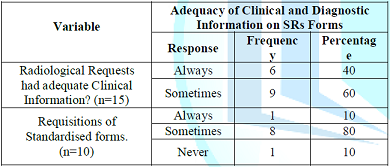

and Report Forms The study showed that

clinicians were divided on the use of standard radiological forms or

Sonographic Requests (SRs) when requesting for DU examinations with 50%

indicating use of standardised or approved radiological forms. The other 50% of

the clinicians indicated infrequent use of standardised radiological forms

(Figure 2). Figure 1: Standard Operating Procedure Presence and Use in the Departments. Figure 2: Sonographic Reports with Inadequate Information. With respect to

clinical information in the Sonographic Requests (SRs), 60% of the clinicians

who indicated that they infrequently used standardised SRs, rarely included all

clinical information on their requests for DU examinations, whereas the other

40% indicated that they included all the necessary clinical details in their

requests. With regard to the quality of the Diagnostic Ultrasound Reports

(DURs), 53% of the clinicians expressed satisfaction with the DURs by the

radiographers. Whereas 47% of the

clinicians indicated that they were not satisfied. Most (80%) of the

radiographers indicated that they did not always receive requisitions for DU

examinations on the standardized request forms, while 10% of the radiographers

indicated that they always received requests on standard forms. Another 10% of

the radiographers expressed that they always received SRs on non-standard forms

(Table 3). Table 3: Adequacy of Clinical and Diagnostic Information on SRs Forms. On

the adequacy of diagnostic information, 90% of the clinicians responded that

they received DURs with inadequate information, whereas 10% of the clinicians

revealed that they always received adequate diagnostic information from the

radiographers DURs. It was further observed that the frequency by which the

clinicians attested that they always received DURs with inadequate information

was 59.3%, whereas 40.7% of the clinicians indicated that the DURs always had

adequate information. Communication

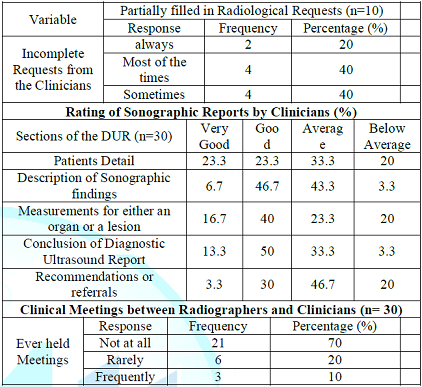

between Clinicians and Radiographers All

the radiographers (100%) had experiences of handling partially filled-in SRs

from the clinicians. There were 40% of the radiographers that indicated that

handling of partially filled-in SRs occurred most of the time, while 20% of the

radiographers stated that they always received incomplete SRs from the

clinicians (Table 4). Table 4: Communication between Clinicians and Radiographers. Most clinicians

(33.3% and 46.7% respectively) rated the radiographers capabilities in handling

the defined aspects of DURs as average with respect to patient details and

recommendations or referrals. With regard to description of sonographic

findings, structural measurements and conclusion of DURs, most clinicians

(46.7%, 40%, and 50% respectively) rated the radiographers capabilities as good

(Table 4). Request

for a Repeat or Second Opinion DURs According

to the findings in this study, 93% of the clinicians sought repeat or second

opinion ultrasound DURs, which essentially included diagnostic ultrasound

examination and only 7% of the clinicians reported that they never requested

for repeat or second opinion DURs following the radiographers DURs. In terms of

the frequency of the requests for repeat or second opinion DURs among the

clinicians who sought this service, most (89.3%) of the clinicians indicated

making such requests occasionally, whereas 7.1% indicated calling for repeat or

second opinion DURs most of the times. With regard to predictability of calling

for second opinion DURs, 3.6% expressed consistency in demanding this service. Clinical

Meetings between Radiographers and Clinicians Most

(70%) of the participants (clinicians and radiographers) indicated that they

never held any clinical meetings in which subjects on or related to DURs were

discussed. About 20% of the participants revealed that clinical meetings took

place though rarely. However, 10% of the participants indicated that they

regularly held meetings (Table 4). All (100%) of the participants were of the

opinion that meetings on DURs were or could be of great importance for

enhancing healthcare delivery. This

study assessed the adequacy of clinical communication between clinicians and

radiographers on the quality of the Diagnostic Ultrasound Reports (DURs) at the

University Teaching Hospital in Lusaka, Zambia. The focus of the study specifically covered subjects

concerned with related work experience and competencies of clinicians and

radiographers, application of Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) in

Diagnostic Ultrasonography (DU), quality of clinical and/or diagnostic

information in DU process involving request for investigation and reporting of

findings. Socio-demographic Profiles of the Participants The participants belonged to the professional disciplines of

clinicians and radiographers respectively, at a University Teaching Hospital

involved in provision of clinical services and teaching. The participants had

different levels of training and experiences. Reference was made to fairly

comparable studies done at public healthcare setting in South Africa and National

Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom (UK).2,11 The interactional communication coherence in requests for a

diagnostic imaging investigation, and the imaging process leading to diagnoses

requires corroborative communication between physicians and radiology practitioners to

optimise outcomes. The radiographers need not helplessly find themselves at a

higher risk as in being blamed for poor quality of DURs. The approach to

realize this goal could be translatable across varied global regions involving

the physicians, radiologists, reporting radiographers and sonographers.11 Edwards et al (2014), in their research, what makes a

good ultrasound report, point to the DURs as usually influenced by the quality

of communication between the practitioners requesting for ultrasound

investigations and those generating ultrasound reports.1 Work Experience of Clinicians and Radiographers at the UTH This study showed that participants gender did not influence

the adequacy of communication between clinicians and radiographers. Equally,

gender orientation did not affect the quality of the DURs (p= 0.08). On the

other hand, it was observed that qualifications and work experience of the

participants in the study had a significant influence on the adequacy of

communication and quality of the DURs generated at the UTH (p=0.02). The findings in this study could be related to those by Booth

and colleagues, in which they revealed that healthcare facilities

where most clinicians and radiographers were highly qualified and with

commendable number of years of effective practical experience, produced

sonographic reports of good quality, which made it easier to reach valid

diagnostic decisions.7,

12 However, in this study

more clinicians (60%) had Masters Degrees in respective areas of specialization

and none of the radiographers could have held competencies derived from such

qualifications. Adequacy in communication between the two professional

dimensions at varied levels of competency could be attributable to quality of

communication affecting the quality of DURs, diagnoses and timely management of

patients needs or treatment of diseases. More specifically, despite the radiographers not possessing

Masters Degrees, the majority (80%) of them underwent specialised training in

Diagnostic Ultrasound whilst (40%) of the clinicians lesser versions of

training, such as short orientation courses in diagnostic ultrasound. In the

midst of statistical evidence pointing to qualifications as affecting the

adequacy and quality of DURs generation, Diagnostic Ultrasound training

gave most of the radiographers an increased advantage over the clinicians in

ultrasonography just as the clinicians had increased advantage in respective

areas of specializations. This consideration requires recognition and

appreciating indispensible need for intra-professional and inter-professional

team work dynamics for optimal healthcare delivery, backed by continuing

professional developments that enhanced essential competencies.13 Use of DU Standard Operating Procedures by Clinicians and

Radiographers The research findings showed that the clinicians were divided

between the use of the standard radiological forms and non-standard medium of

requesting for diagnostic ultrasound examinations with 50% indicating that they

always used the standard forms. The other 50% indicated that they only used the

standard forms at times and mainly used plain papers, consultation forms, or

laboratory request forms for making sonographic requests (SRs) Clinicians who had used alternative forms attributed cause to

non-availability of the standard radiological forms. Such unconventional modes

of communication proved as inefficient as clinicians were not adequately

filling in the required information for the radiographers to carry out

sonographic ultrasound examination. On the other hand, 60% of the radiographers

indicated that they had SOPs in their departments. The majority (83.3 %)

amongst radiographers attested to following the standard way of reporting as

opposed to 16.7% that indicated that they used improvised ways of writing

sonographic reports. Based on comparable findings, as cited above, Bosmas and

colleagues highlighted areas of improvements in the quality of sonographic

reports.8 These authors pointed out Standard

Operating Procedures to be strictly followed by the practitioners in issuing a

diagnostic imaging requests DU and DURs. The use of unconventional request

forms increases the chances of important information being missed from the

request forms, which could be undesirable recipe for substandard DURs.14 The use of unconventional forms greatly hampers the adequacy

of communication between clinicians and radiographers.6, 15 A clear message in the communication of requests is very

important so as for the receiver to comprehend the request and be able to give

appropriate feedback message.

This process also matches

the communication process where the clinicians clinical questions brought

before the intended radiographers led to factual evidence-based answer as feedback in

form of clear DUR.17, 18 With

respect to the above pointed out channel of communication, Most (80%) of the

radiographers indicated that they did not always receive requisitions for DU

examinations on the standardized request forms, implying that the radiographers

feedback encountered communication barriers to quality DUR. About 47% of the

clinicians expressed dissatisfaction with the quality of DURs generated by the

radiographers. Due to this dissatisfaction, radiographers reported that the

majority (93%) of the clinicians dissatisfied with available DUR consistently

requested for repeated or second opinion DURs. Antwi

and his colleagues in their study of assessing the effectiveness of

multicultural communication between radiographers and patients and its impact

on outcome of examinations, reveal that communication becomes effective if

regular meetings among the practitioners are incorporated at every level of

structured organization. This study shows that most (70%) of the participants

had no clinical meetings in which DURs or related subject was discussed. Such a

finding calls for interactional platforms where the clinicians and

radiographers discuss the desirable improvements in communication linked to

quality of DURs. With such interactional forum missing or presumed missing, the

DURs quality is highly compromised as status quo and areas of improvement could

be fragmented and without consensus. It is

hereby reaffirmed that the communication between clinicians and radiographers

at UTH was inadequate. This could have been attributed to clinicians not

providing adequate clinical information on the request forms, coupled with

non-usage of standard radiological forms. In comparative terms, the inadequacy

could equally be premised in the DURs. Inadequate clinical meetings between

clinicians and radiographers influenced clinical communication between these

two healthcare

practitioners at the UTH. In this regard, the quality of the DURs generated by

the radiographers at UTH required methodical approaches to improvement and

minimize widespread sonographic repeated requests for DU and DURs. The

study showed that clinical communication between clinicians and radiographers

was cardinal in expediting detection of diseases and subsequent healthcare

and/or treatment. Such communications also implored provision of appropriate

and adequate clinical communication tools and procedures. Based

on this study identification of approved DU competencies and practitioners by

formal training in ultrasound at degree, postgraduate certificate, or

postgraduate diploma could be recommended. The Continuing Professional

Development (CPD) programmes involving short courses in needy areas should be

part of sonographic practice norms. Clinicians could also undergo short courses

in fundamentals of ultrasonography to enhance intra-professional and

inter-professional healthcare delivery. There should be consistent platforms

for joint clinical meeting where the clinicians and radiographers discuss

sonographic SOPs, SRs and DURs as part of scheduled clinical meetings. The

authors would like to acknowledge support offered to them by the University

Teaching Hospital Management, the Management of the Evelyn Hone College and

Management of the Lusaka Apex Medical University. 1.

Edwards

H, Smith J and Weston M. What makes a good ultrasound report? Ultrasound.

(2014) 57-60. 2.

Makanjee

CR, Bergh A and Hoffmann WA. Healthcare Provider and Patient Perspectives on

Diagnostic Imaging Investigations (2015) African J Primary Health Care Family

Medicine 15: 1-7. https://dx.doi.org/10.4102%2Fphcfm.v7i1.801 3.

Giroldi

E, Veldhuizen W and Mannaerts A. Doctor, Please Tell me its Nothing Serious: An

Exploration of Patients Worrying and Reassuring Cognitions Using Simulated

Recall Interviews (2014) BMC Family Practice 15: 73-60. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-15-73 4.

Pallan

M, Linnane J and Ramaiah S. Evaluation

of an independent, radiographer-led community diagnostic ultrasound service

provided to general practitioners (2013) J Public Health 2: 176-181. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdi006 5.

Antwi

WK, Kyei KA and Quarcoopome, LNA. Effectiveness of Multicultural Communication

between Radiographers and Patients and Its Impact on Outcome of Examinations

(2014) World J Medical Res 6: 12-18. 6.

Field

LJ and Snaith BA. Developing radiographer roles in the context of advanced and

consultant practice (2013) J Medical Radiation Sciences 6: 11-15. https://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fjmrs.2 7.

Booth

L. The radiographer-patient relationship: Enhancing understanding using a

transactional analysis approach (2018) Int J Diagnostic Imaging Radiation

Therapy 4: 323-331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radi.2007.07.002 8.

Bosmans

JML, Weyler JJ, De Schepper AM and Parizel

PM. The Radiology Report as Seen by Radiologists and Clinicians (2011) J

Radiology 259: 184-195. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.10101045 9.

Larson

DB, Froehle CM, Johnson ND and Towbin TJ. Communication in Diagnostic

Radiology: Meeting the Challenges of Complexity (2014) Ame J Radiology 203:

957-964. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.14.12949 10.

Danton

G. Radiology reporting: Changes worth making are never easy (2010) Appl

Radiology 39: 19-23. 11.

Grieve

F, Plumb A and Khan S. Radiology reporting: a general practitioners perspective

(2010) British J Radiol 83: 17-22. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr/16360063 12.

Lockhart

ME, Robbin ML, Berland LL, Smith JK, Canon CL, et al. The sonographer

practitioner: One piece to the radiologist shortage puzzle (2017) J Ultrasound

Med 22: 861-864. http://dx.doi.org/10.7863/jum.2003.22.9.861 13.

Eddy

A. Work-based learning and role extension: A match made in heaven? (2010)

Radiography 16: 95-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radi.2009.12.001 14.

European

Society of Radiology. Good practice for radiological reporting. Guidelines from

the European Society of Radiology (ESR) (2010) Insights Imaging 2: 93-6. 15.

Kasper

J, Légaré F, Scheibler F and Geiger F. Turning signals into meanings-shared

decision making meets communication theory (2011) Health Expect 1: 3-11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00657.x 16.

Leigh

J. A tale of the unexpected: Managing an insider dilemma by adopting the role

of outsider in another setting (2014) Quality Research 4: 428-441. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1468794113481794 17.

Robert

L, Cohen M and Jennings G.A new method of evaluating the quality of radiology

reports (2016) Academic Radiology 13: 241-248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acra.2005.10.015 18.

Bernard

A, Whitaker M and Ray M. Impact of language barrier on acute care medical

professional is dependent upon role (2006) J Professional Nursing 6: 355-358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2006.09.001An Assessment of the Adequacy of Clinical Communication between Clinicians and Radiographers on the Quality of Diagnostic Ultrasound Reports: A Case of the University Teaching Hospital in Lusaka, Zambia

Helen Nampungwe, Foster Munsanje, Titus Haakonde

Abstract

Full-Text

Introduction

Methods

Results

Discussion

Communication between Clinicians and Radiographer

Conclusion

and Recommendations

Acknowledgements

References