Research Article :

Gloria Phebeni, Nomsa

Nxumalo-Magagula, Ruth N Mkhonta and Tengetile R

Mathunjwa-Dlamini Background: In women cervical cancer is the leading cause of

death among all cancers in developing countries, but it can be controlled

through prevention and early detection of precursor lesions. In 2013 there were

223 new cases of cervical cancer in Swaziland with an estimated 118 cervical

cancer related deaths. Most clients suffering from cervical cancer were below

the age of 40 years and were diagnosed in the late stage. The study determined

knowledge, attitudes and practices of women in relation to cervical cancer

screening and treatment at one of the health facilities in the Hhohho Region,

in Swaziland. Methodology: A quantitative-descriptive approach was utilized

among 56 participants selected using purposive sampling. Respondents were women

who came for health care services at the Health Facility s Antiretroviral

Therapy (ART) Department. The collected data were entered into SPSS and

analyzed using descriptive statistics and Pearson s correlation. Findings: Ninety-four percent (94.6%) of the respondents

reported to have heard of cervical cancer, and 96.4% reported that screening

for cervical cancer could detect symptoms before they appeared. Only 1.8% was

aware of the association between cervical cancer and the Human Papilloma Virus

(HPV). Thirty-seven percent (37.5%) of the respondents reported to have ever

screened for cervical cancer. The major reasons reported for not screening were

busy work schedule, and being turned back by nurses. There was a significant relationship

between level of education and knowledge of risk factors for cervical cancer

(r=0.306, p=0.022). Data also supported a significant relationship between age

of the respondents and knowledge on how to protect self from getting cervical

cancer(r=-0.402, p=0.002). Data supported a significant relationship between

knowledge on risk factors and knowledge on how to protect self from acquiring

cervical cancer (r=0.295, p=0.027). Recommendations:

It is recommended that nursing practice should also focus on the provision of

services to the working class by offering cervical cancer screening services on

weekends and public holidays. Nurses need to be more responsive to clients health needs and avoid turning clients back. Background Cervical cancer is a

major public health concern, particularly in developing countries where the

burden is increasing, compared to a downward trend in the developed world. The

incidence per 100 000 in North America is 5.7, Western Europe 8.0, while in

Southern Africa it is a staggering 42.7 [1]. Screening and cryotherapy

of detected lesions can lead to more than 70% reduction of disease-related

mortality. Where screening quality and coverage have been high, invasive

cervical cancer has been reduced by as much as 90%. This indicates the effectiveness

of screening in the population [2]. Hence the need to explore Swazi women s

knowledge, attitude, and practices on cervical cancer. Cervical cancer

screening is available at an affordable cost to the public in Swaziland. Cervical cancer is a fatal

disease at advanced stages, but it can be controlled through prevention and

early detection of precursor lesions. According to World Health Organization

(WHO) (2014), it is the second most common cancer in women, among all types of

cancer worldwide with an estimated 530 000 new cases in 2012. This indicates a

high morbidity, disability, and mortality rate among women. In developing

countries it is the leading malignancy in females, with developing countries

accounting for approximately 85% of both its morbidity and mortality,

indicating a higher burden in developing countries. While lack of resources and

poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa are important issues, it is likely that the

knowledge, attitudes and practices of women in developing countries also play a

major role in these statistics [3-5]. In sub-Sahara Africa, studies

indicate that disease screening is not routine and women do not access health

care or screening because they are unfamiliar with the concept of preventive

health care [6]. Complementing this fact, another study in Zimbabwe reported

that screening services were only offered to women who came to heath

facilities, typically those accessing family planning services, and those with gynecological

symptoms [4]. Nthiga in Kenya revealed that women s

knowledge on cervical cancer and its risk factors were key factors influencing

the uptake of screening services [7]. This means that women with knowledge

deficit on cervical cancer and its prevention are less likely to access

screening services. Adding to these challenges, Sub-Saharan Africa has limited

resources, and is also battling with other major public health problems which

are given priority, such as tuberculosis, malaria, and HIV/AIDS, therefore

cervical cancer is yet to be recognized as a major public health problem. A study conducted by Ngwenya and

Huang in Swaziland revealed that most participants had misconceptions on the

risk factors of cervical cancer and only 5.2% women had been screened. Almost

half of the participants reported that they had to obtain consent from their

spouses to access health services.

Seeking permission from the spouse could be a deterrent to cervical cancer screening.

Men were found to have less misconception on cervical cancer screening and were

more likely to allow their partners to be screened [8]. An ethnographic study

by Malambo revealed that the participants reported that cervical cancer

screening was a laborious process which was complicated by fears of gossip [9]. In Swaziland, cervical cancer is

the most common cancer among women and is one of the causes of death among HIV

positive women. The Human

Papilloma Virus (HPV) Centre, statistics reported that in Swaziland, there

were 223 new cases of cervical cancer and an estimated 118 deaths as a result.

While WHO reported that there were 200 cancer-related deaths in Swaziland,

45.3% of the deaths were related to cervical cancer. Most cases of cervical cancer

were in women below the age of 40 years among these a relative number were aged

20-30 years and were diagnosed at late stages [3,10,11]. Visual Inspection with

Acetic Acid (VIA) is a simple, cost effective method that provides

diagnosis and treatment at one visit, however, data has shown that few women

have knowledge about these services and this in turn influences their attitude

and practices, making them screen for cancer only when they have signs and

symptoms. To support this, Swaziland Breast and Cervical

Cancer Network (SBCCN), reported that in 2014 a total of 3797 women

received cervical cancer screening at three main VIA sites around the country

and the results showed that of all the women who received cervical screening

10% of them had some damage on the cervix ranging from early stage to full

blown cancer [10]. Therefore there are important gaps between services offered,

awareness of women on the preventability of cancer and the actual uptake of

these services by women, prompting the researcher to conduct a study among

women which aims to understand more on their knowledge, attitudes and

practices. To address this, Swaziland Breast

and Cervical Cancer Network (SBCCN), together with the Ministry of Health (MoH)

are making great strides to improving accessibility of VIA in clinics, with

plans to open several VIA sites at clinics in 2015 [10]. This is in order to

increase accessibility to the services with the aim of helping women to screen

earlier, thereby reducing morbidity and mortality rates. Preventive services

include vaccination of teenagers (12-14 years) with the HPV vaccine. However,

this vaccine is not yet available in Swaziland. In Swaziland, screening

detection by VIA services is made available to sexually active females

annually, until they reach menopause. Following menopause the Papanikolaou

smear becomes relevant [3]. If nothing is done to encourage women to seek

preventive measures early, cervical cancer will continue to be a major health

care burden and many women will die from the disease. Purpose

of the study This study determined knowledge,

attitudes and practices of women regarding cervical cancer screening at one of

the health care facilities in Hhohho Region. In addition, the associations

between knowledge, attitude and practices were examined. Objectives

of the study · To

determine the knowledge of women regarding cervical cancer and screening. · To

describe the attitude of women regarding cervical cancer and screening. · To

identify the practices of women on cervical cancer screening. · To

examine the association between women s socio-demographic variables, knowledge,

attitudes, and practices on cervical cancer and screening. A descriptive-correlational

quantitative design was used to study the knowledge, attitudes, and practices

of women related to cervical cancer attending one of the health facilities in

Swaziland in the Hhohho region. Purposive sampling was used to obtain sample,

and data were collected through interviewer-administered questionnaires, in

January 2016. Respondents were women aged 21 years and above, of any

nationalities, who were attending for ART services, willing and consented to

participate in the study. Women attending ART were included in the study

because they were at high risk for cervical cancer. Using an effect size of

0.50, alpha of 0.05, and power of 0.80 the sample size was 56 participants

[12,13]. The questionnaire utilized was

adapted from John, titled Knowledge,

attitude, practice and perceived barriers for premalignant cervical screening

among women aged 18 and above in Songea Urban, Ruvuma [14]. The key areas from

the questionnaire were socio-demographic variables, knowledge on cervical

cancer and screening, attitude towards screening for lesions, and practices

of women in relation to cervical cancer screening. Socio-Demographic

Characteristics of the Participants There were six questions in this

section which included age, level of education, occupation, marital status,

parity and religion. Knowledge

on Cervical Cancer and Screening This section had 12 questions. It

enquired on the knowledge of respondents on cervical cancer including

prevention, risk factors, symptoms and treatment, as well as costs. In addition

this component enquired knowledge on availability of screening for premalignant

cervical lesions, screening interval, eligibility for screening and methods

used for screening. Attitude

towards Screening for Lesions There were seven questions on a

Likert scale which assessed the respondent s feelings on the gravity of

cervical cancer in Swaziland, and if they felt they were at risk of acquiring

cancer. There were also questions on how they felt about screening for

premalignant cervical lesions and if there was any harm caused by screening. In

addition, respondents were asked if they thought the procedure was expensive,

their feeling on the importance of screening and lastly, if they were in a

position to screen. Practice There were four questions in this

section which asked about whether the respondents had ever been screened, how

many times and when was the last time they were screened. Analysis

and ethical considerations The data were entered into SPSS,

and was analyzed using descriptive statistics and Pearson s correlation.

Permission to conduct the study was sought and approved by the Swaziland

Ministry of Health Scientific and Ethics Committee. The participants were

requested for a written informed consent [15]. Results The

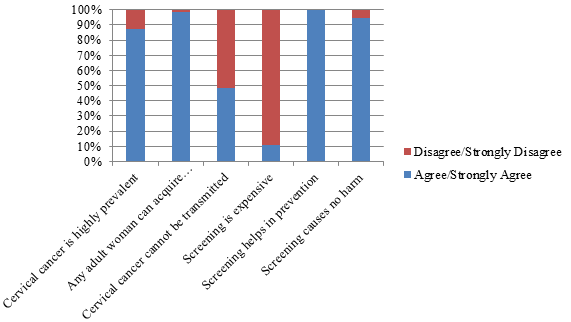

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Study Respondents Age:A total of N=56 respondents participated in the study. The respondents ages ranged from 21 to 48 years. The mean age

was 28.96 years with a standard deviation of 5.23 years. Most (55%, n=31) respondents

were aged between 21-29 years, and 41% (n=23) were aged between 30-39 years. Education:

Most of the respondents (67.9%, n=38) had attained secondary education and

14.3% (n=8) had tertiary education. Only 1.8% (n=1) of the respondents reported

that they had no formal education. Employment

status:Half (50%, n=28) of the respondents

were unemployed and only 33, 9% (n=19) reported that they were employed. Marital

status: Fifty-three percent (53.6%, n=30) were

married, 41.1% (n=23) were single and only 3.6% (n=2) of the respondents

reported that they were cohabiting. Parity:A majority, (92.9%, n=52) had between 1-4 children, and 7.1% (n=4) of the

respondents had more than five children. The respondents socio-demographic characteristics are summarized

in Table 1. Table 1:

Respondent socio-demographic characteristics (N=56). Research

Objective 1: To Determine The Knowledge Of Women Regarding Cervical Cancer and

Screening. Knowledge

about cervical cancer: Most (94.6%, n=53) had heard of

cervical cancer and only 5.4% (n=3) of the respondents reported that they had

never heard about cervical cancer. Source

of information about cervical cancer: Eighty-nine

percent (89.3%, n=50) heard from the media, 67.9%, (n=38) from health workers,

7.1%, (n=4) from friends, family and neighbors and 3.6% (n=2) of the

respondents reported that they learnt about cervical cancer from brochures and

posters. Knowledge

about cervical cancer screening frequency: A

majority of the respondents 96.4% (n=54) reported that screening could detect

early symptoms of cervical cancer. All respondents (100%, n=56) reported that

early detection led to a good health outcomes. Concerning who should screen,

96.4% (n=54) of the respondents reported that all women need to be screened for

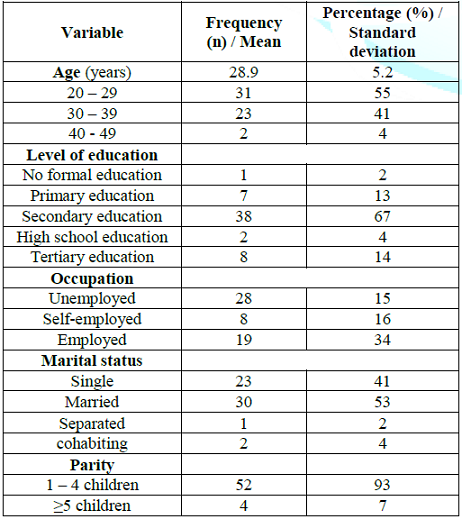

cervical cancer. Concerning frequency of screening, only 35.7% (n=20) reported

that cervical cancer screening should be done once a year. Twenty-five percent

(25%, n=14) reported that screening should be done twice a year and 17.9%

(n=10), reported that screening should be done three times a year. A summary of

the respondents knowledge on frequency for cancer

screening is presented in Figure 1. Figure 1:

Respondent s responses on how often one should screen for cervical cancer. Knowledge

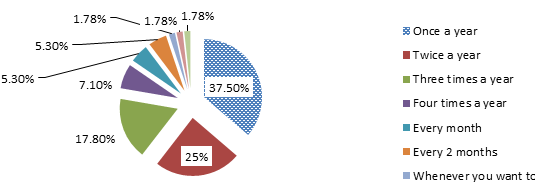

on signs and symptoms of cervical cancer: Most respondents

(51.8%, n=29) reported that foul smelling vaginal discharge was a sign of

cervical cancer and 48.2%

(n= 27) did not know that a foul vaginal discharge was a sign of cervical

cancer. Whereas 42.9% (n=24) reported that Lower Abdominal

Pain (LAP) was also another sign of cervical cancer while 51.7% (n=32) did not

know LAP was a sign of cervical cancer. A further 17.9% (n=10) reported that

vaginal bleeding was a sign of cervical cancer and 82.1% (n=46) did not know that vaginal bleeding

was a sign of cervical cancer. Figure 2 below shows a summary of respondents feedback on signs and symptoms of cervical

cancer. Figure 2: Respondents

responses on signs and symptoms of

cervical cancer (N = 56). Knowledge

on risk factors and prophylaxis for cervical cancer: Seventy

eight percent (78.6%, n=44) of the respondents reported unprotected sex with

more than one partner was a risk factor for acquiring cervical cancer.

Concerning prevention of cervical cancer, 58.9% (n=33) reported both the use of condoms

and limiting number of sexual partners as ways of preventing cervical cancer.

Among respondents, 51% (n=28) reported that regular screening was a preventive

measure for cervical cancer. Only 1.8% (n=1) reported to have ever heard of HPV

infection. Management

of cervical cancer: Chemotherapy was

reported as the commonest modality for treatment for cervical cancer by 35.7%

(n=20) of the respondents, and 28.5% (n=16) reported surgery as the commonest

intervention in the treatment for cervical cancer. Most respondents (98.2%,

n=55) revealed that cervical cancer can be cured in its earliest stages. A

large proportion of respondents (44.6%, n=25) reported that it was very

expensive to be treated for cervical cancer, while 28.6% (n=16) reported that

it was reasonably priced. Research

Objective 2: To Describe the Attitude of Women Regarding Cervical Cancer and

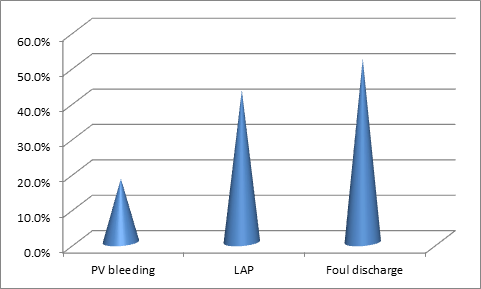

Screening (n=56). Awareness of the severity of

cervical cancer was high as 87.5% (n=49) of the respondents believed that cervical

cancer was prevalent in Swaziland and leading cause of death among all cancers.

A majority (98.2%, n=55) also believed that any adult woman could acquire

cervical cancer. Slightly more than half of the respondents (51.7%, n=29)

thought that cervical cancer could be transmitted from one person to another

while 48.3% (n=27) thought that cervical cancer could not be transmitted form

one person to another. All the respondents (100%, n=56) believed that screening

for cervical cancer helped in early detection and prevention of cervical cancer

and that they would screen if it was free and harmless. All (100%, n=56)

respondents felt that they would screen for cervical cancer if it was free and

harmless. However, 94.6% (n=53) of the

respondents believed that screening was harmless. Eighty-nine percent (89.3%,

n=50) respondents believed that screening was not expensive and 10.7% (n=6)

respondents believed that screening for cervical cancer was expensive. A score

of 15 or more indicated a positive attitude, while a score of 14 and below

indicated a negative attitude. All the respondents attained a score of 15 or

more on all the variables in the attitudes section, reflecting an overall

positive attitude. The respondents attitudes towards cervical cancer are summarized

in Figure 3 below. Figure 3:

Participants responses on attitudes

towards cervical cancer screening. Research

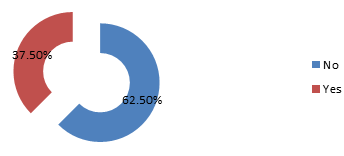

Objective 3: To Identify the Practices of Women on Cervical Cancer Screening Only 37.5% (n=21) of the

respondents reported having ever screened for cervical cancer, amongst which

88% (n=16) had screened in the past year. Among those who had ever screened

80.9% (n=17) had screened once, and 19.1% (n=4) of the respondents reported

that they had screened more than once. Figure

4 below illustrates participants responses on having ever screened for cervical

cancer. Figure 4:

Participants responses on having ever

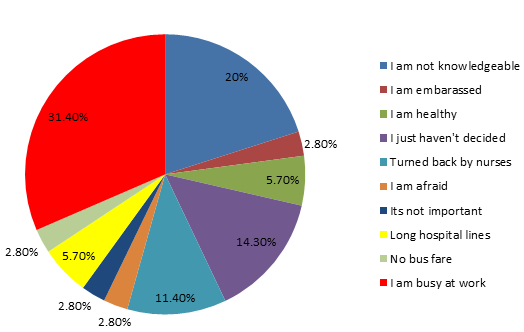

screened for cervical cancer (N = 56). Reported

reasons for not screening: Among the respondents who

reported to have never screened for cervical cancer, 31.4% (n=11) revealed that

they were busy at work. Twenty percent (20%, n=7) of the respondents reported

that they had knowledge deficit on cervical cancer and screening, hence they

did not screen. Fourteen percent (14.2%, n=5) reported that they had not yet

decided to screen for cervical cancer, and 11.4% (n=4) of the respondents

reported that they went for screening but were turned back by nurses. Figure 5 below illustrates reasons for

not screening among the respondents. Figure 5:

Reasons reported by respondents for not screening for cervical cancer. Research

Objective 4: To Examine the Association between Respondents Socio-Demographic Variables, Knowledge,

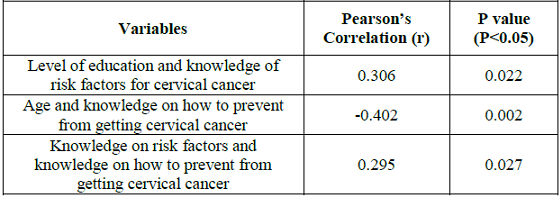

Attitudes and Practices on Cervical Cancer and Screening. There was a significant

relationship between level of education and knowledge of risk factors for

cervical cancer (r=0.306, p=0.022). This means that as level of education

increased, so did the knowledge on risk factors for cervical cancer and Screening. Data also

supports a significant relationship between age of the respondents and

knowledge on how to protect self from getting cervical cancer(r=-0.402,

p=0.002). This means that knowledge on protecting self from cervical cancer

decreased as the age of the respondent increased. Data supports a significant

relationship between knowledge on risk factors and knowledge on how to protect

self from acquiring cervical cancer (r=0.295, p=0.027). This means that being

more knowledgeable on risk factors increased knowledge on how to protect self

from acquiring cervical cancer. The association between respondents socio-demographic

variables, knowledge, attitudes and practices on cervical cancer is

summarized in Table 2 below. Table 2:

The association between socio-demographic variables and knowledge (N=56). Education Most respondents in the study had

attained secondary level education. These findings are supported by reports from

the study conducted by Ahmed et al. [16] in Nigeria on cervical cancer

screening, who also revealed that there was a higher percentage of respondents

with secondary education level in their study. This could mean that women are

getting more information through education. In contrast, a study conducted in

Nigeria by Nnodu et al. [17] reported that a larger proportion of the

respondents had primary level education, with only a smaller percentage having

attained secondary or higher level education. Employment

status Most respondents in this study

were unemployed. This is consistent with findings by other researchers. Al-Meer

et al., in Qatar reported that more than half of their respondents were

unemployed as well. This could be attributed to a lack of education and low

economic status [18]. Marital

status Most respondents in this study

were married. This is consistent with findings by Al-Meer et al. [18] who also

noted that most of their respondents were married. This could mean that more married

women, are unemployed, allowing them to seek health care services during

working hours. In contrast, single women may need to go to work to maintain

their families and may not get time to attend the clinic. Number

of children In this study, a majority of the

respondents had between 1-4 children, with a very small percentage having more

than four children. In contrast to Al-Meer et al. [18] who reported that most

of their respondents had four or more children. They attributed this to

cultural factors and religious practices. Education, availability and

accessibility of free contraception enable women in urban areas to have fewer

children. Knowledge

on Cervical Cancer This study has shown that a large

number of the respondents had heard of cervical cancer, which is consistent

with previous research. Adekanle et al. [19], Oche et al. [20] in Nigeria also

reported a high level of knowledge on cervical cancer. Consistent with John in

Songea, the most common means of information dissemination in the current study

was the media, followed by health care workers. This highlights the important

role media and health care workers play in disseminating information [14]. Knowledge

on Symptoms of Cervical Cancer Knowledge on symptoms of cervical

cancer was high. The most common symptom of cervical cancer that the

respondents knew was foul-smelling vaginal discharge. It seems, to some extent

that women are knowledgeable about the signs and symptoms that appear later in

the stage of cancer. This could be attributed to high knowledge levels. This

finding is contrary to Maree, Lu and Wright who reported that in South Africa

only a small proportion of the respondents identified smelly vaginal discharge

as a symptom, and a majority of the respondents could not identify a single

warning sign of cervical cancer. This could be attributed to the fact that

respondents in Maree, Lu and Wright study also had knowledge deficit on general

information about cervical cancer [21]. Knowledge

on Risk Factors of Cervical Cancer The knowledge on risk factors is

an important element in the prevention of cervical cancer. Although respondents

in the current study had high knowledge level on risk factors, however,

consistent with Nthiga they had knowledge deficit on Human Papilloma Virus (HPV)

infection and its link to cervical cancer [7]. The knowledge deficit on

awareness of the relationship between HPV and cervical cancer can affect

prevention and control as it is likely to be difficult for women to protect

themselves from HPV if they are not aware that it increases the risk of getting

cervical cancer. Knowledge

on Screening Concerning knowledge on whether

screening could detect symptoms before they appeared, a majority of the

respondents were aware of this fact. This is in harmony with Nakalevu in Fiji,

who revealed that a large proportion of respondents believed that screening was

beneficial as it could detect pre-cancerous cells. This means that women are

aware that screening for cervical cancer is beneficial [22]. With respect to frequency of

screening, a majority of the respondents were aware that screening should be

carried out annually. This means that women know how often they need to have

cervical cancer screening. Knowing when to screen can be attributed to access

to information. However, in contrast, a study conducted by John revealed that a

larger proportion of the respondents had knowledge deficit on when to screen

for cervical cancer. John attributed this discrepancy to cultural barriers that

make it challenging for women in developing countries to talk about sexual and

reproductive health issues [14]. Attitude

towards Cervical Cancer Screening Consistent with John [14]

respondents reported that screening was important in the prevention of cervical

cancer thus reflecting a positive attitude towards screening for cervical

cancer. In a study by Balogun, Odukoya, Oyediran, and Ujomu in Nigeria

respondents reported that people should screen even when they feel well. This

fact emphasizes the importance of prevention [23]. In harmony with Nakalevu, the

respondents felt that cervical cancer was a public health concern and most of

the respondents felt that they were susceptible to cervical cancer [22]. These

results indicate that women are aware of the danger of cervical cancer. All the

respondents in this study reported that they could avail themselves to

screening if screening was free and harmless. This means that women have

misconceptions and myths about services provided because they are not aware

that screening for cervical cancer is free and harmless. Practices

on Cervical Cancer Screening In the current study, less than

half of the respondents reported having ever screened for cervical cancer. The

reason for not screening in this study was the respondent s busy schedule. This

finding is contrary to Oche, Kaoje, Gana, and Ango, who reported that

respondents were not screening because they felt they were not at risk [20].

Again, Adekanle, Adeyemi and Afolabi, also indicated high knowledge level on

cervical cancer, but low screening among respondents [19]. Hence knowledge did not

necessarily translate into practice. Although reasons vary for not screening;

these barriers to screening need to be overcome in order to increase screening levels.

Most of the respondents in this study were not aware that screening for

cervical cancer is done annually. This lack of knowledge is reflected in their

practices. Of the few respondents in this study who reported ever having

screened for cervical cancer, most had screened once and only a minority had

screened more than once. This still indicates poor practices among women in

relation to screening for cervical cancer. Association

between Variables Knowledge on prevention of

cervical cancer decreased as the age of the respondents increased. This could

be attributed to more access to information in younger women who are more

likely to have recently completed their education. In contrast, Assoumou et al.

[24] in their study in Gabon reported that older participants, those who had

ever been married and those with medium to high monthly incomes were more

likely to have a good knowledge on cervical cancer. This could be due to being

more educated and being able to afford private health care [24]. Recommendations

With reference to the study

findings, the following recommendations were made: Nursing

Practice All health facilities need to

offer provider-initiated-screening services for cervical cancer in order to

make screening accessible to many women. Nursing practice should also focus on

the provision of services to the working class by offering these services on

weekends and public holidays in order for them to screen during their time off

from work. Nurses should teach women about HPV infection and its link to

cervical cancer, given the high prevalence of HIV in the country which

exacerbates cervical cancer. Nurses also have to make women aware of the

availability of the vaccine in the private sector for those who can afford it.

Older women need to receive more information about cervical cancer, its

symptoms and risk factors given that the younger women in this study had more

knowledge compared to their older counterparts. Nursing

Education Currently, nurses are being

trained on screening for cervical cancer in the field, limiting the number of

those who can offer these services to the clients. A certain number of the

respondents who sought screening services were turned back by nurses and this

could be one of the reasons why they do not get to be screened. Therefore,

training on screening should be part of the curriculum for nurses and midwives

in order to increase level of skill among nurses. Nursing

Research The respondents had a high level

of knowledge and positive attitude, but only a few had screened for cervical

cancer. Other studies could be done focusing mainly on the barriers to

screening and how they can be overcome. Since this study was done in an urban

setting, other studies of the same nature can be done in rural settings, to

find out about rural women s knowledge, attitude and practices in relation to

cervical cancer and be compared to results in urban areas. Summary

and Conclusion The respondents showed a high

level of knowledge on cervical cancer. Most of the respondents reported that

having unprotected sex put one at risk of contracting cervical cancer, although

only a very small percentage were aware of the role Human Papilloma virus

played in causing cervical cancer. The respondents attitude was positive as they reported that

screening helped in the detection and prevention of cervical cancer and they

would screen if it was free and harmless. However a majority of the respondents

did not screen despite being aware of the risk factors of cervical cancer and

benefits of early

screening. There was an association between

level of education and knowledge of risk factors. This is attributed to the

fact that most respondents had attained secondary level of education and above.

There was a negative correlation between age of respondents and knowledge on

prevention of cervical cancer. The younger women knew more than the older women

about ways of preventing cervical cancer. There was also a significant

correlation between knowledge on risk factors and knowledge on prevention of

cervical cancer. The respondents who were aware of the risk factors were most

likely to be aware of the ways of prevention of cervical

cancer. Limitations Given that only participants that

agreed to participate in the study were interviewed, using only those who

volunteered was a limitation in this study. To reduce the number of women who

did not understand the questions, siSwati questionnaires for all participants

were used. The results of this study can be

generalized with caution because of the sample size was small given that there

was limited time and resources. In addition, the sample was obtained using

non-probability, purposive sample. 2. Singh S and Badaya S. Factors Influencing Uptake of Cervical Cancer

Screening Among women in India; a Hospital Based Pilot Study(2012) J

Community Med and Health Edu 2: 1-6. https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-0711.1000157 3.

World Health Organization. (2014). Cervical Cancer.Geneva, Switzerland. 4.

Mupepi SC, Sampselle CM and

Johnson TRB. Knowledge, attitudes and demographic factors influencing cercal

cancer screening behavior in zimbabwean women (2011) J Women s Health

20:943-952. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2010.2062 5.

Ntekim

A. Cervical cancer in Sub Sahara Africa, topics on cervical cancer with an

advocacy for prevention (2012) R Rajamanickam (Ed), InTech, Croatia. 6. Lim JNW and Ojo

AA. Barriers to utilisation of

cervical cancer screening in Sub Sahara Africa: a systematic review (2017) Euro J Cancer Care 26: e12444. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12444 7. Nthiga AM. Determinants of cervical cancer

screening uptake among women in Embu County, Kenya (2014) Semantic Scholar. 8. Ngwenya D and Huang S. Knowledge, attitude and practice on cervical

cancer and screening: a survey of men and women in Swaziland (2018) J Public

Health 40: 343-350. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdx174 9.

Malambo N. Cervical screening in Swaziland: an ethnographic case study

(2015) Master of Science Thesis, Harvard University. 11. HPV Centre Fact sheet

number380 (2013).

12. Ononogbu U, Almujtaba M, Modibbo F, Lawal I, Offiong R, et al. Cervical

cancer risk factors among HIV-infected Nigerian women (2013) BMC Public Health

13: 582. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-582 13.

Lipsey MW and Hurley S M. Design sensitivity: statistical power for

applied experimental research (2009) Leonard Bickman and Debra J (Eds) Sage

Publication, USA. 15. Ministry of Health (2011) Swaziland Cervical Cancer

Guidelines, Government printer, Swaziland. 16. Ahmed SA, Sabitu K, Idris SH and AhmedR. Knowledge, attitude and

practice of cervical cancer screeningamong market women in Zaria, Nigeria

(2013) Nigerian Med J 54: 316-319. https://doi.org/10.4103/0300-1652.122337 17. Nnodu O, Layi E, Mustapha J, Olaniyi O, Adelaiye R, et al. Knowledge

and attitudes towards cervical cancer and human papillomavirus: a nigerian

pilot study (2010) Afr J Reprod Health 14: 95-108. 18. Al-Meer FM, Aseel MT, Al-Khalaf J, Al-Kuwari MG and Ismail MSF.

Knowledge, attitude and practices regarding cervical cancer and screening among women in Qatar (2009) Eastern Med Health J

17: 855-861. https://doi.org/10.26719/2011.17.11.855 19. Adekanle DA, Adeyemi AS, and Afolabi AF. Knowledge, attitudes and

cervical cancer screening among female secondary school teachers in osogbo,

Southwest Nigeria (2011) Academic J Cancer Res 4: 24-28. 20. Oche MO, Kaoje AU, Gana G and Ango JT. Cancer of the cervix and

cervical screening: currentknowledge, attitude and practices of female

healthworkersin sokoto, Nigeria (2013) Int J Med and Medical Sci 5: 184-190. 21.

Maree

JE, Lu XM and Wright SCD. Cervical cancer: South African women s knowledge,

lifestyle risks and screening practices (2012)Africa J Nursing and Mid 14: 104-115. 22.

Nakalevu SM. The knowledge, attitude, practice and

behavior of women towards cervical cancer and pap smear screening (2009) Fiji

school of medicine, Fiji. 23. Balogun

MR, Odukoya OO, Oyediran MA and Ujomu PI. Cervical cancer awareness and preventive practices: a

challengefor female urban slum dwellers in lagos,

nigeria (2012) African J Reproductive Health 16: 75-82. 24. Assoumou SZ, Mabika BM, Mbiguino AN, Mouallif

M, Khattabi A, et al. Awareness and knowledge regarding of cervical cancer, Pap

smear screening and human

papillomavirus infection in Gabonese women (2015) BMC Women s Health 201515:37.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-015-0193-2 Nomsa

Nxumalo-Magagula, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Swaziland, Mbabane,

Swaziland, Southern Africa, Tel: +268-2517-0728, Email: nmagagula@uniswa.sz

Phebeni

G, Nxumalo-Magagula N, Mkhonta RN and Mathunjwa-Dlamini TR. Knowledge,

attitudes and practices of women attending one of the health facilities in Hhohho

region, Swaziland, in relation to cervical cancer and screening (2019) Edel

J Biomed Res Rev 1: 31-37. knowledge, Attitude, Practices, Cervical cancer,

Screening, Women.Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Women Attending One of the Health Facilities in Hhohho Region, Swaziland, in Relation to Cervical Cancer and Screening

Abstract

Abstract

Full-Text

Introduction

Methods

Discussion

References

*Corresponding author

Citation

Keywords