Research Article :

Eunjung Kim*, Leanna J Standish and M Robyn Andersen This paper compared Recurrence and Morality rates among women with

breast cancer who received all recommended treatment (Receivers) and who did

not (Decliners). 427 women

were recruited through integrative oncology clinics and the Cancer Surveillance

System (CSS) registry in Western Washington State. Secondary data analysis were

conducted using descriptive statistics, t-tests, X2 tests, and R. Self-reported

data included household income and comorbidity; medical records included dates

of diagnosis, recurrence and last visit with medical oncologist; and CSS

registry data included demographic, disease characteristics, and records on

recommended treatments and receiving/declining them, and date of death. 9% of Receivers and 2% of

Decliners experienced a Disease Free Survival (DFS) limiting event commonly a

recurrence, while 3% of Receivers and 2% of Decliners died. After controlling

for stage at diagnosis and cohort, no difference was found on the Adjusted

Hazard ratio of recurrence or mortality between Receivers and Decliners.

Adjusted Hazard ratio of Decliners relative to Receivers was 0.29 (95% CI; 0.04

– 2.22, p = 0.22) for DFS and 0.50 (95% CI: 0.04, 6.49, p = 0.59) for

mortality. Better

clinical predictors among Decliners may be related to no rate difference in

recurrence and mortality between Decliners than Receivers. Approximately

3.5 million women have breast

cancer in the U.S. and this number goes up each year; in 2019, an estimated

268, 600 women will be newly diagnosed with breast cancer and 41,760 will die

from it [1,2]. However, among these women, about 6-13.8% of women with breast

cancer willingly decline recommended chemotherapy [3-5], 9%

radiotherapy [6] and 14% hormone therapy [7]. Limited evidences suggest that

when women did not receive surgery, relative risk of estimated 10-year

mortality was 1.58 times higher than among Receivers, while the relative mortality was

1.54 times higher when women did not receive chemotherapy [8]. In another study, the risk for having another breast cancer among woman

who did not receive recommended systemic treatments (i.e., chemotherapy,

hormone therapy) was 1.9 times, and risk for death was 1.7 times during an

average 7.3 years of follow-up [5]. Recently, Johnson et al. found that 5-year

survival rate of breast cancer patient was 58.1% among women who did not

receive all treatments, whereas it was 86.6% for women who received all

treatments; Cox hazard ratio was 5.68 [9]. However, lack of information still

existed on the recurrence and mortality of women who did receive surgery but

choose not to receive at least one adjuvant therapy

(i.e., chemotherapy, radiotherapy, hormone therapy) after surgery. Overall

objective of this study was to compare differences in recurrence and mortality

between Receivers and Decliners. In this paper, Receivers indicates women who

received all doctor recommended medical breast cancer treatments including

surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and hormone therapy. Decliners are those

who voluntarily declined all or part of the doctor recommended adjuvant therapy

(i.e., chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and hormone therapy) after

receiving surgery. This study used longitudinal and correlational study

design. This study reports results from the secondary analysis of the baseline

and 5-year follow up data from the Breast Cancer Integrative Oncology Study, in

which 427 women were recruited through integrative oncology clinics in greater

Seattle area and the Cancer

Surveillance System (CSS) registry in Western Washington State. Sample

criteria included: 1) 18 years of age or older, 2) biopsy-pathology verified

diagnosis of breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ, 3) surgery was conducted,

4) their doctor recommended at least one adjuvant treatment among chemotherapy,

radiotherapy, and hormone therapy, 5) clear indication of receiving or

declining recommended treatment, and 6) clear abstracted records of the

following dates: diagnosis, last visit with medical oncologists or recurrence

or second primary

cancer diagnosis (for analysis of DFS), and death as applicable. Data were collected from participants self-reports

(household income and comorbidity), oncologists medical chart review (diagnosis

date, last visit date with oncologists, and recurrence date), and Cancer

Surveillance System (CSS) registry (age and stage at diagnosis, ethnicity,

marital status, Estrogen

and Progesterone

Receptors status, side of breast cancer, receiving/declining recommended

treatments, and last contact/death date if indicated) in Western Washington

State. All data were analyzed using SPSS 20 software and R

Version 3.2.2 [10]. The comparison of survival and DFS between Receivers and

Decliners was analyzed with Cox proportional hazards regression, using the

coxph function in R. For the analysis of DFS time was computed as going from

date of diagnosis to time of DFS limiting event or death for those who did die

but did not recur (n = 2). Those who did not die or recur were censored at the

time last known to be alive and not recurred, i.e. the last visit to the

oncologist. Analysis of survival was similar, except that time of death was

used as the outcome. These analyses controlled for stage of cancer at diagnosis

and type of oncology care received. Kaplan-Meier survival and DFS curves were

generated using the survfit function in R. The

original study obtained the permission from the Institutional Human Subjects

Review Committee of the Bastyr University and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research

Center and each subject provided informed written consent before participation.

For the current study, the committees from Bastyr University, Fred Hutchinson Cancer

Research Center and the University of Washington

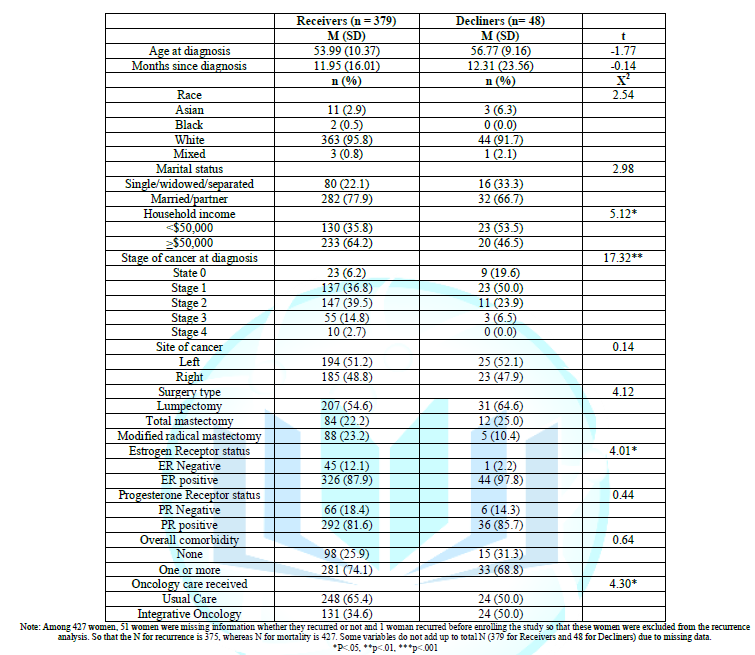

approved to conduct secondary data analysis using a de-identified data set. As shown in Table

1, Decliners tended to have less household income, earlier stage of breast

cancer at the time of diagnosis, more estrogen positive receptor status, and

more frequently received integrative naturopathic oncology

care than Receivers. No other differences were found. As depicted in Table

2, overall 31 women (30 Receivers and 1 Decliner) experienced a DFS

limiting event, commonly a recurrence of cancer and 13 women (12 Receivers and

1 Decliners) died during 5 years of follow-up. The recurrence rate was 9%

(30/334) among Receivers and 2% (1/41) among Decliners, while mortality was 3%

(12/379) among Receivers and 2% (1/48) among Decliners. After controlling for

stage at diagnosis and type of oncology care received, no difference was found

on the Adjusted Hazard ratio of DFS or mortality between Receivers and

Decliners. Adjusted Hazard ratio of Decliners relative to Receivers was 0.29

(95% CI; 0.04 – 2.22, p = 0.22) for DFS and 0.50 (95% CI: 0.04, 6.49, p = 0.59)

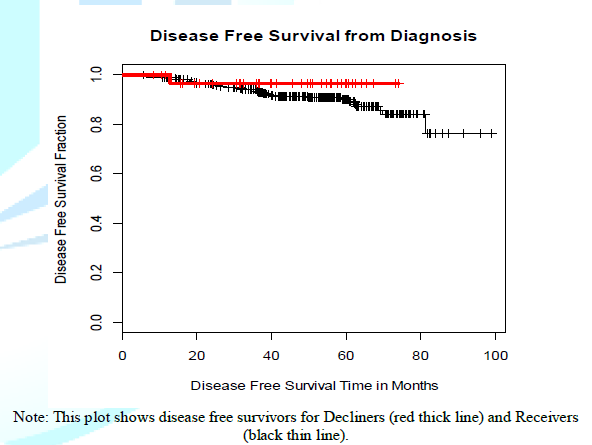

for Mortality. Figure

1

shows the Kaplan-Meyer curves for comparing disease free survival time between

Receivers and Decliners, which was not statistically significant. The x-axis

represents time since diagnosis and y-axis represents the fraction of women who

are alive and disease free at each time. All women (100% or 1.0 fraction) start at the top of

the y-axis, indicating all women, at the time of diagnosis, have not

experienced DFS limiting event or death. The lines go down at the times at

which a woman in that group died or experienced a DFS limiting event. Women

who did not die or recur are shown in the plot as a small vertical tick mark

which indicates the time at which that woman was censored, i.e. the time at

which she was last known to be alive and disease-free. Red thin lines represent

Decliners and black thin lines represent Receivers. Figure

1: Disease free survival between Receivers and Decliners. Overall, the recurrence rate was 9% among Receivers

and 2% among Decliners, while the mortality rate was 3% among Receivers and 2%

among Decliners. These rates are much lower than Saquib et al.s finding; they

found recurrence rate of 6.63% for Receivers and 19.21% for Decliners and

mortality rate of 10.14% for Receivers and 11.30% for Decliners [5]. The

Adjusted Hazard Ratio of 0.29 for recurrence and 0.50 for mortality in the

current study is much lower than the ratio of 2.35 for recurrence and 3.05 -

5.68 for mortality found in previous studies [5,9]. This difference may be

related to data collection time; Saquib et als data were from 1995 - 2000 and

Johnson et al.s data were from 2004 - 2013, whereas our data were from 2012 -

2017. In looking at the difference in findings where we

found non-significant differences such that Decliners did not

demonstrate poorer outcomes, this may be in part because Decliners in this

study tended to have earlier stage of cancer at diagnosis and more estrogen

positive receptor status. Suggesting that Decliners in this study may have been

aware that their risks of poor outcomes were low when they choose to decline adjuvant treatment. However,

for R analyses this study controlled the stage of cancer at diagnosis, and when

these adjustments were added the non-significant differences remained but were

reduced. It is possible that decliners had more detailed knowledge of their

condition from their doctors than we could control for using stage. Of note also might be the fact that participants in

this study were predominantly white women living in an urban area with good

access to medical care who generally received guideline consistent care and

reported having been very involved in making decisions about their treatment [11].

Our previous study found that overall, 11.2% (48/427) of women declined at

least one adjuvant treatment recommended by their medical doctors after their

surgery; 8.8% (22/251) chemotherapy, 10.5% (33/314) radiotherapy, and 13.3%

(45/339) hormone therapy. Decliners of conventional adjuvant treatment in this

study were very involved in their treatment decision making, compared with Receivers. In this context, Decliners in this study were

generally women who choose not to receive one or more adjuvant therapies

on a therapy by therapy basis and did not include women who were denied

treatment based on counter indications due to co-morbidities or poor health, or

lack of access [11]. These data may thus present a best-case scenario for

self-determination and patient informed decision-making about adjuvant care. Study participants were mostly White Americans and

the sample size for Decliners was much smaller than Receivers. Repeating the

study with more women who have more diverse, income, educational, ethnic and

cultural backgrounds would be important. There were 51 women whose recurrence

status was missing in medical record, which decreased sample size. Recording recurrence

of all individuals with cancer would be important. And it would be nice if

these data are collected by CSS registry. Some Receivers may not 100% adherent

to all adjuvant treatments; conversely some Decliners might have received some

adjuvant treatments later; however, this information was not collected. Our study found no significant difference,

suggesting that in some cases Decliners may be patients

with good prognosis; receiving treatment in their case would represent

over-treatment. To our knowledge, this is the first study that demonstrated no

statistically significant difference in the rate of recurrence and death

between Receivers and Decliners. This finding is not congruent with earlier

studies that have shown that Decliners were at a higher risk of recurrence or

death. And it is not clear why the results were not consistent, although we

have attempted to present some possible explanations. Acknowledgement This

paper discusses secondary analysis using the data from the Breast

Cancer Integrative Oncology: Prospective Matched Controlled Outcomes Study

which was awarded to Drs. Andersen and Standish, from NIH, NCCAM, R01 AT005873. *Corresponding author: Eunjung Kim, Department

of Family and Child Nursing, University of Washington, USA, Tel: 206-543-8246,

Fax: 206-543-6656, Email: eunjungk@uw.edu Breast cancer, Recommended conventional

treatments, Receivers, Decliners, Recurrence, MortalityRecurrence and Mortality Rates Among Receivers and Decliners of Conventional Adjuvant Breast Cancer Treatments

Abstract

Objectives: Full-Text

Highlights

Introduction

Methods

Design,

sample, setting, and procedures

Instruments

Data

sources

Data

analysis

Ethical

Considerations

Sample

Characteristics

Recurrence

and Mortality

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusion

References

Keywords