Case Report :

Within NHS Lothian an advanced nurse practitioner is required to have completed Masters level education in patient history taking, clinical examination and non-medical prescribing (NMP) before they can prescribe independently. A definition for advanced nursing practice is followed by an overview of the roles and responsibilities of the Hospital at Night Team (HAN) at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh. A case study based on a commonly encountered request for patient review illustrates the application of NMP in advanced nursing practice and provides the clinical context for the discussion that follows. The focus of the discussion is the complexities of prescribing for an elderly patient including immunosenescence, poly pharmacy and adverse drug reactions. Standards for education and continuing professional development (CPD) are required to support the safe practice of NMP. This is especially relevant to HAN non-medical prescribes due to the wide range of medications they prescribe. For the purposes of confidentiality all identifying patient details have been removed.

Within

NHS Lothian, all nurse

practitioners who wish to prescribe must first complete two Masters level

modules in patient history taking and clinical examination. Only then may they

progress to the third and final module on NMP and be classed as advanced

nurse practitioners [1]. This is not true of all health boards but, in

terms of professional accountability and liability, if you are to prescribe

safely and appropriately, it is logical that you must first be able to

establish a working diagnosis. The

Royal College of Nursing [2] defines advanced nurse practitioners as: The

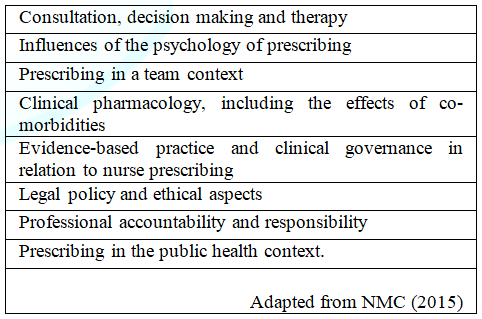

complexity of NMP is reflected by the Nursing

and Midwifery

Council’s Standards for NMP [3] which are summarized in Table 1. Table 1: Nursing and Midwifery

Standards for non-medical prescribing. Within

NHS Lothian the HAN team consists of senior and advanced nurse practitioners (ANPs),

medical registrars, clinical

development fellows, foundation year one and two doctors and, more

recently, clinical support workers. Working in the acute hospital setting, HAN is

a medical emergency team whose primary remit is to provide out of hours care

via planned reviews of unstable patients and by responding to

referrals for the review of newly deteriorating patients. The team is also responsible

for clerking new admissions across various specialities. As the service runs on

a system of telephone triage, a key role within HAN is that of the coordinator

who is responsible for the allocation of patient reviews to the appropriate

team member within a timeframe that reflects the acuity of the situation. One

non-medically prescribing ANP per night is responsible for providing a remote

service to three community

hospitals and one rehabilitation hospital in and around Edinburgh. This

remote service ranges from telephone advice and the generation of remote

prescriptions to travel to these hospitals to assess and treat deteriorating

patients either on site or by moving them to an acute site. A

referral was made to the HAN team requesting review of a patient with chest

pain and a national Early Warning Score (NEWS) of 14. NEWS is an evidence-based

score reflecting the level of acuity of a patient’s condition and is an

essential requirement for the speedy triage of an acutely unwell patient [4].

The history given by the nurse included the information that the patient was on

oral antibiotics for a chest infection but also had a cardiac history. The

nurse had administered Glycerol

Trinitrate (GTN) spray. When the patient’s pain did not settle she

administered a second dose, rechecked his vital signs and noted he was now

pyrexial and acutely short of breath. She commenced the patient on oxygen (O2)

therapy, recorded a 12 lead electrocardiograph

(ECG) and sent bloods for serum biochemistry and hematology. The

patient was hot, flushed, diaphoretic

and tachypnoeic with an increased work of breathing and use of the accessory

muscles of respiration. He looked frightened and was only able to reply with

one word answers. The pain was in the left side of his chest and worse on

inspiration. It had been present earlier in the day but had been mild so he did

not inform nursing staff until it recurred, waking him from sleep. On

physical examination the patient had a rapid irregular heart rate, no added

heart sounds, a capillary refill time of 4 seconds with cool peripheries, no peripheral

oedema and his calves were soft and non-tender. Chest auscultation showed

decreased breath sounds at his left base with coarse crepitations to the left

mid-zone, a few fine crepitations in the right base and scattered wheeze

throughout. Deep breathing caused him to cough and to experience pain in his

chest. On percussion, his lungs sounded dull at the left base and his lung expansion

was equal. Due to his level of dyspnoea it was not possible to lie him flat to

perform a full abdominal examination but he had no obvious signs of an acute

abdomen on palpation or ausculation. His fluid balance was not recorded. He was

not diabetic but a random capillary blood glucose check was slightly high at

11.2 mmols. His vital signs showed a temperature of 38.8 degrees Celsius, a

heart rate of 143, blood pressure of 92/46, respiratory rate of 32 and oxygen

saturations of 68% on 4 liters of oxygen. A

twelve lead ECG showed sinus tachycardia with atrial ectopic and T wave

inversion in the infero-lateral leads. In this context, these changes can

indicate a non-ST elevation myocardial

infarction (NSTEMI) [5] secondary to organ dysfunction [6]. An arterial

blood gas (ABG) was taken on high flow oxygen. Inflammatory markers, a lactate,

coagulation screen, troponin and blood cultures were sent to the laboratories.

An urgent portable chest x-ray

was ordered. His

CXR showed consolidation suggestive of a left sided pneumonia. His blood

results showed raised inflammatory

markers and a high lactate, an acute-on-chronic kidney injury with a safe

potassium level and a positive troponin result. His arterial blood gas showed

type two respiratory failure so his high flow oxygen was titrated down, aiming

for target oxygen saturations 88-92%. His normal oxygen saturations trended at

87-89%. Sepsis

secondary to pneumonia Initial

Management Following

a review of his drug kardex for allergies, current medication and potential

interactions, prescriptions were written for intravenous morphine, an anti-emetic,

high flow oxygen and a salbutamol nebulizer as well as an initial fluid bolus

of 250 milliliters of plasmalyte. His oral antibiotics were escalated to

intravenous for a community-acquired pneumonia

as per local guidelines. Due to the acuity of the situation, an explanation of

the plan was given to the patient but not discussed in any detail. Education

and experience as an ANP provides the necessary knowledge and skill to assess a

patient and generate a working diagnosis. Further education and registration as

a non-medical prescriber contributes to timely initiation of treatment, meeting

sepsis standards of initiating treatment within an hour of diagnosis [7]. If an

ANP could not prescribe independently, a doctor would have to review the patient

a second time before prescribing the appropriate antibiotics, resulting in a

delay to treatment. Given the high morbidity and mortality of sepsis, delay can

lead to a poorer outcome. Evidence underpinning current sepsis management

guidelines clearly demonstrates the need for early recognition and treatment of

patients presenting with sepsis

[8]. Due

to the presence of pre-morbid and co-morbid factors, the elderly are

predisposed to sepsis, often presenting atypically [9] with a compromised

immune response leading to an increased risk of developing systemic infections

and an impaired vascular response [10]. Immunosenescence

is the term used to describe immune compromise secondary to aging. Defined as a

combination of oxidative stress, altered apoptosis and cytokine mediated

inflammatory response and with a profound effect upon survival [11] it can be

seen that senescence adds a further layer of complexity to the issue of sepsis

in the elderly. In terms of deciding whether to treat a pneumonia as hospital

or community-acquired, the length of stay of the patient is relevant (in this

case two days) as the causative organisms are different and therefore require

different antibiotics [12]. Antimicrobial

stewardship is a major and very current factor in terms of trying to avoid

antimicrobial resistance [13]. In this instance, the clinical status of the patient

dictated the prescription of antimicrobials. The presence of multiple

co-morbidities and polypharmacy

mean the risk of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are two to three times more

likely in the elderly [14] and the benefit versus risk of treatment should be

considered before any prescription is written [15]. As

a non-medical

prescriber it is your responsibility to ascertain and guide a patient’s

expectations about their treatment by forming a partnership with them that

takes into account their beliefs about health and medication [16]. Involving

the patient in the planning of their care is the guiding principle without

which all other aspects of the prescribing process become less effective [17].

These patient centered discussions should also include longer term management

considerations such as the wishes of the patient and their family should

further deterioration occur [18]. However, as this case study shows, there are

situations where clinical need takes precedence and discussions have to wait

until the situation has stabilized. At

this point it is worth emphasizing the individual nature of each HAN ANP’s

prescribing formulary. Starting with a core formulary developed during the NMP

Master’s module, this formulary is expanded post registration as a non-medical

prescriber to include NHS Lothian’s Drug Formulary. Consequently, ANPs within

HAN work with a broad formulary comprising multiple types of medication across

many adult specialties rather than the limited formularies used by specialist

ANPs who may only be able to prescribe a set group of drugs within their area

of expertise. The

following list of drugs prescribed over the course of one HAN night shift

illustrates the diversity of our prescribing practice: Anti-epileptic As

the legislative barriers to nurses prescribing independently have been removed

[24], NMP has become an asset that can be utilized by ANPs working across a

broadening spectrum of specialities and healthcare institutions. An evaluation

of the safety of NMP found that it compared favorably with medical prescribing

with an improved patient experience, antimicrobial stewardship and safe

prescribing practice [25]. Prescribing is a complex skill affected by many

factors and further research is required on the impact of NMP and rate of prescribing

errors [26]. A systematic review [27] found that the level of experience of a

non-medical prescriber had a direct effect on confidence to prescribe both in

the learning phase and on implementation of NMP in their role. NMP

in the acute setting has become an integral part of the care given by ANPs. By

providing fast and effective treatment to deteriorating patients it is both

safe and well received by patients. A robust and structured system of

guidelines and standards of practice supports the autonomy of the role and

clinical supervision by a designated medical practitioner provides ongoing

support and guidance. 1. Taylor

P. Change, for the better (2015) Royal College of Nursing Scotland. Edinburgh. 2. Royal

College of Nursing (2018) RCN Credentialing for advanced level nursing practice,

United Kingdom. 3. Nursing

and Midwifery Council (NMC) (2015) Standards of proficiency for nurse and

midwife prescribers. 4. Royal

College of Physicians (2017) National early warning system (NEWS 2)

Standardizing the assessment of acute-illness severity in the NHS, United

Kingdom. 5. Bangalore

S, Owlia M. Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (2017) BMJ Best Practice,

BMJ Publishing Group, United States. 6. Landes U, Bental T, Orvin K, Vaknin-Assa H, Rechavia

E and et al., Type 2 myocardial infarction: A descriptive analysis and

comparison with type 1 myocardial infarction (2016) J Cardiol 67:51-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjcc.2015.04.001 7. National

Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2016) NICE 51 Sepsis: Recognition,

diagnosis and early management. Secton 1.7, United Kingdom. 8. Daniels

R. Surviving the first hours in sepsis: getting the basics right (an intensivists

perspective) (2011) J Antimicrob Chemother 66:11-23. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkq515 9. Murdoch

I, Turpin S, Johnstone B, MacLullich A and Losman E. Geriatric Emergencies (2015) Wiley

Blackwell, Chichester, England. 10. Martin

S, Perez A and Aldecoa C. Sepsis and immunosenescence in the elderly patient: A

Review (2017) Front Med 4:1-10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2017.00020 11. Ventura

MT, Casciaro M, Gangemi S and Buquicchio R. Immunosenescence in aging: Between

immune cells depletion and cytokines up-regulation (2017) Clin Mol Allergy 15. https://dx.doi.org/10.1186%2Fs12948-017-0077-0 12. Morgan

AJ and Glossp AJ. Severe community acquired pneumonia (2016) BJA Education 16:167-172.

https://doi.org/10.1093/bjaed/mkv052 13. National

Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2016) Quality standard 121

antimicrobial stewardship, United Kingdom. 14. Greenstein

B. Drugs in pregnancy and extremes of age (ed) Greenstein B (2009b) Trounces Clinical

Pharmacology for Nurses, Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh 413 - 420. 15. National

Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2017) Multimorbidity and

Polypharmacy, United Kingdom. 16. Healthcare

Improvement Scotland (2012) Working together to improve the use of medicines,

NHS Scotland. 17. McKinnon

J. Towards prescribing practice (2007) John Wiley and Sons Ltd, Chichester,

England 35-57. 18. Scottish

Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (2014) Care of the deteriorating patient

SIGN 139, Scotland. 19. Croskerry

P and Nimmo G. Better clinical decision making and reducing diagnostic error

(2011) J R College of Physicians Edinburgh, Scotland 41: 155-162. https://doi.org/10.4997/JRCPE.2011.208 20. Petty

D. Ten tips for safer prescribing by non-medical prescribers (2012) Nurse

Prescribing 10: 251-256. 21. Stewart

D, MacLure K and George J. Educating non-medical prescribers (2012) Br J Clin

Pharmacol 74: 662-667. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04204.x 22. Nursing

and Midwifery Council (NMC b) (2015) The Code, Standards of Conduct, Performance

and Ethics. 23. Scottish

Government (2016) Transforming Nursing, Midwifery and Health Professions (NMaHP)

Roles: pushing the boundaries to meet health and social care needs in Scotland,

Advanced Nursing Practice Scottish Government.

24. Rideout

A. Non-medical prescribing in Scotland (ed) Franklin P (2017) Non-medical prescribing

in the United Kingdom, Springer International Publishing. 25. Scottish

Government (2009) An evaluation of the expansion of nurse prescribing in Scotland,

Scottish Government. 26. Cope

L, Abuzour A and Tully M. Nonmedical prescribing: Where are we know?? (2016)

Ther Adv Drug Saf 7:165-172. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177%2F2042098616646726 27. Abuzour

A, Lewis P and Tully M. Practice makes perfect: A systematic review of the

expertise development of pharmacist and nurse independent prescribers in the

United Kingdom (2017) Res Socio Admin Pharm 14: 6-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2017.02.002 Jayne RW. Advanced Nurse

Practitioner, NHS Lothian, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, Scotland, Tel: 01312423888, E-mail: jayne.worth@luht.scot.nhs.uk Worth

JR. Non-medical

Prescribing in the Acute Setting: A Case Report (2018)

Nursing

and Health Care 3: 42-44 Advanced nursing practice, Non-medical prescribing, Elderly,

SepsisNon-medical Prescribing in the Acute Setting: A Case Report

Abstract

Full-Text

Introduction

“… Educated at Masters Level in clinical

practice and have been assessed as competent in practice using their expert

clinical knowledge and skills. They have the freedom and authority to act,

making autonomous decisions in the assessment, diagnosis and treatment of

patients.”

Hospital at

Night

Case Study

Presentation

Examination and

Investigation

Results

Working

Diagnoses

Positive troponin: potential

causes - sepsis, acute kidney injury or Type 2 MI secondary to sepsis. How does NMP

contribute to patient care?

Factors to be considered

when prescribing for an elderly patient

Safety of NMP

Opiates

Antibiotics

Insulin

Saline

nebulizer

Decision

not to prescribe

Anti-arrhythmic

drug

Resuscitation

fluids

LaxativesConclusion

References

*Corresponding author:

Citation:

Keywords