Research Article :

Objective: To determine the prevalence of latent tuberculosis

infection among Healthcare Workers (HCWs) in Al- Thawra Modern General Hospital. Methods: We carried out cross sectional study to determine

the prevalence of Latent Tuberculosis Infection (LTBI) among HCW. Two-steps Tuberculin

Skin Test (TST) was performed among

health care workers (HCWs) in Al -Thawra Modern General Hospital (TMGH) Sanaa-

Yemen during the year 2016. We included all health care workers in the hospital. Out of 466 total HCWs 426 were fulfilled the

inclusion criteria. Questionnaire was

distributed to HCWs and information related to demographic data, profession,

and duration of work, individual and in the family history of Tuberculosis (TB)

was recorded. TST was done by a single investigator using the standard Mantoux

test. The reaction was read 48 to 72

hours after injection, and the widest axis of indurations was measured by a

standardized palpation method. Those with negative result were advised to come,

after1- 2 weeks for second step TST. Results: The total number of health workers in the hospital

were 466, Eligible cases who fulfilled the including criteria were 426. The remaining either excluded or not present

at the time of study. Of them 232 (54.5%) were males and 194 (45.5 %), were females

with a ratio of 1.2:1.269 (70%) were positive for TST. The positive result was

highest among radiology assistant and laboratory worker represented 91%, 80%

respectively, while 76% of doctors found positive for TST. There was an

increase in TST reactivity with an older age, and there is a positive correlation

between work duration and TST reaction. Latent tuberculosis

infection is prominent among HCW who work in high-risk departments. This

suggests that some TBI develops via in-hospital infection. Tuberculosis (TB) is an infection

caused by mycobacterium

tuberculosis; commonly it affects the lungs (pulmonary), but can affect any

organ in the body [1]. World Health Organization (WHO) considered that,

tuberculosis (TB) is a global public health problem affected 10 million people worldwide,

with 1.6 million died. More than, 95% of the cases and 97% of deaths occur in

development countries [1,2]. The disease continues to be a problem in industrialized

countries as well, mostly in immigrants populations, in elderly individuals

whose latent infection is reactivated. TB is spread from person to

person through the air. When people with lung TB cough, sneeze or spit, they

propel the TB germs into the air. A person needs to inhale only a few of these germs

to become infected. Several

studies reported that, transmission of TB infection found to be High

among students and healthcare workers as a nosocomial transmission,

when biosafety guidelines were not strictly followed [3,4]. It was estimated

that, about one-quarter of the worlds population has latent TB, which means

people have been infected by TB bacteria but are not yet ill with the disease.

The risk of transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from patients to Health

Care Workers (HCWs) is greatest in facilities with a high burden of infectious Tuberculosis

(TB) cases [5]. Transmission of TB in health care facilities can be reduced or

prevented with the implementation of effective infection control measures [6]. There

are other risk groups whom are susceptible to TB infection, such as intravenous

drug users, patients with end stage renal disease, HIV positive patients, the homeless.

Several studies have demonstrated the importance of M. tuberculosis transmission in students and among nurses [4-7]

Nosocomial transmission, especially between TB/HIV co-infected patients and

health care workers, when biosafety guidelines were not strictly followed

[3,4]. Despite the importance of LTBI, the tuberculin

skin test was, until recently, the only test available for its diagnosis [8]. The

TST measures hypersensitivity response to Purified Protein

Derivative (PPD), a crude mixture of antigens, many of which are shared

among M. Tuberculosis, Mycobacterium bovis Bacilli Calmette-Guérin

(BCG) and several Non Tuberculous Mycobacteria (NTM). The TST has limitations

with respect to accuracy and reliability [8,9]. Advances in genomics and immunology

have led to a promising alternative, the in vitro interferon γ(IFN- γ) assay

[8,9], based on the concept that T cells of infected individuals release IFN- γ.

The QuantiFERON-TB assay

(Cellestis Limited, Carnegie, Australia) was the first commercially available

IFN- γ assay. The PPD-based QuantiFERON-TB test was approved by the US Food and

Drug Administration in 2001 [10-12] demonstrated higher prevalence of

tuberculin skin testing among health care workers than general population

[13-15], necessitate effective

infection control measures [6]. Currently, the CDC guidelines

recommend that HCWs receive tuberculin testing on entry to the workplace and an

assessment should be made to assign a risk category to HCWs in an institution

and thus the frequency of screening should be determined according to the risk [16].

Each institution should use its own surveillance data from tuberculin skin

testing to assess the specific risk category of its HCWs. Many healthcare

institutions have mandatory annual tuberculin screening for their HCWs. Annual

screening provides significant protection for HCWs as most active cases develop

within the first few years after the initial infection, however CDC did not

make specific recommendations concerning treatment of the latent infection [17].

Health care workers screening in

Saudi Arabia revealed that, the overall prevalence of positive TST among HCWs

at king Abdulaziz university hospital was 78.9%, 60.0% for Saudi Arabian

compared with 81.0% for non-Saudi Arabians [18]. In Yemen, the prevalence of

tuberculosis among adults population (15-45 years) was 136/100,000 with

mortality rate about 21/100,000 [2,19]. Unfortunately, prevalence rates of TB

among health care workers in Yemen are not known, even though TB is considered

as one of the most common chronic infectious

diseases in the country [19]. This study was carried out to

identify the prevalence of latent tuberculosis

infection among health care workers in the main referral hospital (TMGH) at

Sanaa City Yemen. Using tuberculin skin test rather than QuantiFERON- test for

two reasons firstly there is an agreement between both tests in various reports

[20-22] and secondly, the cost of QuantiFERON- test is higher, in the presence

of the lack of resources, and also the absence of the political commitment in

the health authority of this country. Explanation for including both

general and specific objectives: These are fundamental in any

health research. General objective is a broad statement of what the researcher

hopes to accomplish. They create a setting for the research. Specific

objectives are statements of the research question(s). After statement of the

primary objective, secondary objectives may be mentioned. General

objective To determine the prevalence of LTB

among health care workers in Al- Thawra Modern General Hospital, Sanaa -Yemen. Specific

objectives This study was a descriptive -

cross sectional study carried out in Al Thawra Modern General Hospital; which

is a referral hospital located in the center of capital of Yemen. The hospital

well equipped and has 1000 beds. All HCWs working at the medical, surgical, emergency, intensive care units,

laboratory and radiology departments were included in this study. Any

participant with a history of old TB or positive TST before joining the

hospital, any family history of TB or close contact more than one year, any

HCWs with employment or training less than one year in the hospital or refused

to participation in the study were excluded. A questionnaire was design to

document demographic data such as age sex, profession, department, duration of

work in the hospital, past history and family history of tuberculosis. Pilot

test of questioner was done and ambiguous question were reworded. We excluded health care worker if

his or her age below 18 years, working in the hospital less than 1 year, has

history of tuberculosis or resent contact to Tuberculous patients and those

refusing the TST or refused to repeat the second step test. TST was done by a single

investigator using the standard

Monteux intradermal injection. The standard tuberculin test consists of 0.1

ml (5 tuberculin units) of PPD administered intracutaneously, usually in the

forearm, using a 26 gauge needle after sterilization with normal saline. The

reaction is read 48 to 72 hours after injection and the widest axis of

indurations was measured by a standardized palpation method with a flexible

ruler after a period of 48-72 hours, by the same investigator. The conduct and

interpretation of tuberculin skin tests were based on current guidelines of the

CDC Committee on Latent

Tuberculosis Infection [23]. For the purpose of our analysis,

two cut–off point used to define the positive TST reaction, an indurations of

10 mm or greater regarded as positive and an indurations of 15mm or more is

regarded as strong positive. Those with negative result advised to come after 1-2

weeks for second step TST & those who agreed, underwent 2nd step TST after

1-2 weeks. Those reacted strong positive TST were investigated to rule out

active TB [23,24]. BCG vaccination history was

ignored in this study, because the health care workers are high risk group and

booster doses of BCG is not performed in Yemen routinely. Data collected from

all participants were coded and entered in the computer and analyzed using SPSS

software. Frequency tables and determination of significant differences among

variables were performed by the chi-squared test and Student t-test, P value ≤

5 considered significance. Ethical

Consideration The total number of health

workers in the hospital were 466, Eligible cases whom fulfilled the including criteria

were 426. The remaining either excluded or not present at the time of study. Of

them 232 (54.5%) were males and 194 (45.5%), were females with a ratio of

1.2:1. Of the 426 participants 215 (50.5%) were positive from the 1st step TST and

211 (49.5%) were 1st step TST negative and needed to do the 2nd step. However,

40 (19%) were unable to repeat the TST for different reasons. Thus, 171 (81%)

were able to do the 2nd step TST, of whom 54 (32%) turned to be positive and

117 (68%) had negative result. The total number found to be positive from first

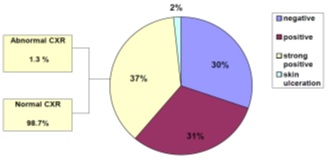

and second steps were 269 (70%) and 117 HCWs (30%) were negative. Out of the

269 positive cases, 144 (37%) were strong positive (>15mm), 119 (31%) were

just positive (10mm-15mm), 6 (2%) were strong positive with skin ulceration.

those with strong positive TST were screened for active TB and only 2 were

found to have radiological evidence of apical fibrosis, one of them found to

has active TB (Figure 1). Figure

1: Tuberculin skin test reaction results. Distribution of positive results

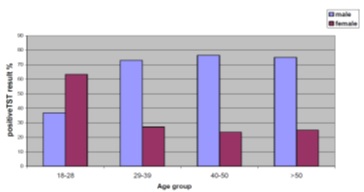

among age group of both sexes is shown in Figure

2. The prevalence of positive TST among young age group (18-28), were 56%

while the elder group (40-50 years) were 89% and this rate reach 100% among

GHCWs of above 50 years old.The positive TST were 197 (70%)

Yemeni HCWs, 62 (66%) Indian, 6 (100%) Philippines and 4 (100%) other

nationality, there is no significant P value 0.362 (Table 1). Figure

2: Distribution of positive TST according to the age

& sex.

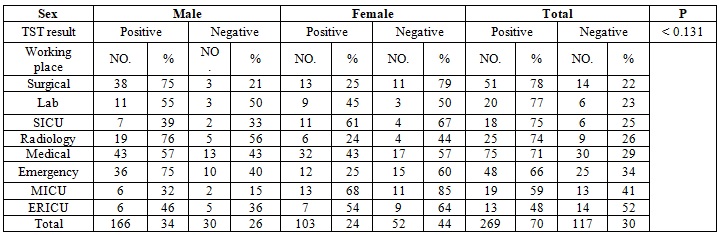

Table

1: Distribution of positive TST according to the sex

& nationality. The distribution of positive TST

among HCWs in the different departments is shown in Table 2. There were no significant differences between them, with

prevalence rate in the surgical department, laboratory, radiology medical

wards, emergency department accounted for (78%,77%,74%,71%,66%) respectively.

However, the lower rate 48% was found among HCWs in the emergency intensive

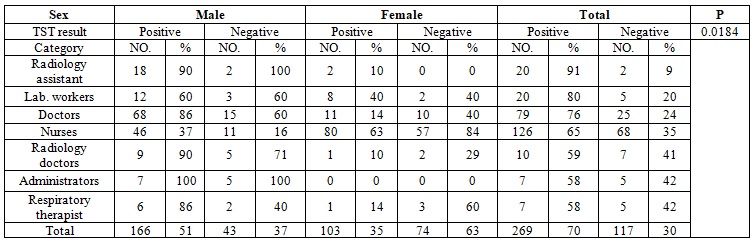

care unit. Regarding to employment (professional) category, the highest

positive result was recorded among radiology assistants (91%) followed by

laboratory workers (80%), doctors (76%), nurses (65%), radiologists (59%), administrators

(58%) and respiratory therapist (58%), the differences found to be significance

with P. value of 0.0184 (Table 3).

Table

2: Distribution of positive TST according to the sex

& working place. Table

3: Distribution of positive TST according to the sex and

employment category. There is a deference in TST

result in female with the use of female veil (the dress used by the female in

the Islamic countries in which they cover their body with it including their

face leaving only their eyes) which was 52% compared to females did not use

veil (55%), but this differences did not have statically significant with P

value <0.80. In this study the prevalence of LTBI

among HCWs at Al-Thawra Modern General Hospital Sanaa Yemen was 70%. This high

rate is expected in the country where prevalence of TB among general population

reached to 136/100.000 and incidence of TB is about 82/100,000 [2,19]. This make HCWs in the hospital

expose to high incidence of TB infection. Reports from Turkey showed that the

incidence of TB was 199.9/100,000 among health care workers, compared with

40.8/100,000 in the general population, giving a relative risk of approximately

5 times greater among health care workers than in the general population [25]. Similar

result was reported from Poland where high rate of TB incidence among HCWs was

204-721/100,000, compared to general population which was 24.3/100,000 [26]. In

Malawi, it was found that the incidence of TB among health care workers in 40

hospitals that treat TB patients was twelve times greater than that of the

general adult population [27]. In a

study conducted in Brazil, it was found that nurse students were more

susceptible to infection with M.

tuberculosis than the general population at a rate of 10.5% and 0.5%

respectively [28]. While in Finland, the risk is lower among health care

workers than in the general population because Finland has an excellent TB

control program. However, the risk of developing TB among HCWs is dependent on

several factors such as occupational category, age and use of TB infection

control measures in the workplace [29,30]. In our study the positive result

of STT was higher in males (62%) than the female (38%), this could be explained

by the fact that the female in our country joined the health profession too

late compared to their male counterpart another peculiar culture in Yemeni

females, that most of them wearing the traditional veil (alhijab or alnikab)

which may possibly protect them against infection. Moreover, the frequency of TST

was higher in female expatriate nurses, and Yemeni female nurses not wearing

the veil (55%) than in those with veil (52%) with no veil has a possible

protective effect on female nurses against TB infection, statistically

significant difference. These findings may suggest that

the veil has a possible protective effect on female nurses against TB

infection, but this point needs further study. In this study we found high

prevalence of positive TST among elder age group ≥ 40years and in those with

longer work duration which is consistent with the findings reported in HCWs in

high incidence countries like (India, Russia, and Georgia) [31-33]. There were

variations of LTBI among different employment categories, in our study, with

radiology technicians was caught the highest rate of LTBI (91%) and the lowest

rate was among administrators. Similar results had been reported

from other places [34,35]. These variations could by related to environmental

factor and or close contact with TB patients. The environment in Radiological rooms

are often poorly ventilated, therefore, droplet

nuclei may stay in the air for hours or even days. While the lowest rate

among

administrators is due to less contact with TB patents and has good ventilation.

The lowest rate of LTBI among administrators is due to less contact with

patients. The respiratory therapist has lower rate of positive TST in our study

unlike the other reports as in Poland this is because this occupation is new in

our hospital (TMGH) which started 2 years ago and more time is needed to have

positive conversion. Regarding types of professionals

we found surgeons and laboratory personnel acquired the high rate of LTBI (78% &

77%) respectively. These high rates could be related to nature of work in our

hospital as it is general referral hospital, most patients with complicated TB

admitted to surgical word for surgical intervention such as, chest empyema and

lung cavity. The procedures and manipulation of lesion/s produce minutes

droplets which are more penetrable than larger droplets and expose the surgeons

to LTBI [2]. On the other hand Laboratory personnel received body fluid like

blood, sputum, fluid from pleural abdomen, pus etc., from different department

for bacteriological analysis and exposed them to acquire TB infection,

especially in hospital with lack of infection control program. Similar result

has been reported from other study [35]. In

our study the doctors have higher percentage of TST than the nurses in contrast

to other studies, where nurses have been found to have a higher risk for

developing TB [36,37] in spite of the fact that nurses are the first point of

contact with patients in the out-patient departments and are continuously in

contact with patients in hospital wards. They also take sputum samples,

including those obtained by induction from infectious patients, increasing

their risk of exposure. This

paradox could be explained by the fact that majority of the nurses are females

and once they got married they quit the job so they dont stay longer in the

hospital in addition to the fact that most of the females are wearing the veil

which could work as a mask for them. High suspicion of tuberculosis by the

clinician, adequate infection-control measures by the hospital authorities and

early identification of latent tuberculosis infection in healthcare workers by

occupational specialists form the essential components of a comprehensive

package to prevent tuberculosis in healthcare workers [17]. We found high LTBI rates among

HCWs at Al-Thawra Modern General Hospital in Sanaa Yemen with male predominance

with higher positivity among high risk working places & risky occupation.

This suggests that some TBI develops via in-hospital infection. In order to enhance the

protection of both health care workers and hospitalized patients, effective control

and preventive measures for TB, including yearly tuberculin testing of health

care workers, should be considered. We are thankful to all the health

workers at Althawra Teaching Hospital for participation in this study. Our

thanks to Al Awlaki lab for their great help in supplying the tuberculin tests

to all the participants. 1. Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimates of future global tuberculosis

morbidity and mortality (1993) MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 42: 961-964. 2. Dye

C, Scheele S, Dolin P, Pathan V and Raviglione MC. Consensus statement. Global

burden of tuberculosis: Estimated incidence, prevalence and mortality by country

(1999) JAMA 282: 677-686. 3. Sokolove PE, Mackey D, Wiles J and

Lewis RJ. Exposure of emergency department personnel to tuberculosis: PPD

testing during an epidemic in the community (1994) Ann Emerg Med 24: 418-421. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0196-0644(94)70178-4 4. Zaza

S, Blumberg HM, Beck-Sagué C, Haas WH, Woodley CL, et al. Nosocomial

transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Role of health care workers in outbreak

propagation (1995) J Infect Dis 172: 1542-1549. 5. Harries

AD, Maher D and Nunn P. Practical and affordable measures for the protection of

health care workers from tuberculosis in low-income countries (1997) Bull World

Health Organ 75: 477-489. 6. Blumberg

HM, Watkins DL, Berschling JD, Antle A, Moore P, et al. Preventing the

nosocomial transmission of tuberculosis (1995) Ann Intern Med 122: 658-663. 7. Maciel EL, Meireles

W, Silva AP, Fiorotti K and Dietze R. Nosocomial Mycobacterium tuberculosis

transmission among healthcare students in a high incidence region, in Vitória,

State of Espírito Santo (2007) Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 40: 397-399. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0037-86822007000400004 8. Huebner

RE, Schein MF and Bass JB Jr. The tuberculin skin test (1993) Clin Infect Dis. 17:

968-975. 9. Andersen P, Munk ME, Pollock JM

and Doherty TM. Specific immune-based diagnosis of tuberculosis (2000) Lancet 356:

1099-1104.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02742-2 10. Mazurek

GH and Villarino ME. Guidelines for using the QuantiFERON-TB test for

diagnosing latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention (2003) MMWR Recomm Rep 52: 15-18. 11. Chan ED, Heifets

L and Iseman MD. Immunologic diagnosis of tuberculosis: a review (2000) Tuberc

Lung Dis 80: 131-140.

https://doi.org/10.1054/tuld.2000.0243 12. Jackett

PS, Bothamley GH, Batra HV, Mistry A, Young DB et al. Specificity of antibodies

to immune dominant mycobacterial antigens in pulmonary tuberculosis (1988) J

Clin Microbiol 26: 2313-8. 13. Maciel EL, Viana

MC, Zeitoune RC, Ferreira I, Fregona G, et al. Prevalence and incidence of

Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in nursing students in Vitória, Espírito

Santo (2005) Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 38: 469-472. https://doi.org/S0037-86822005000600004 14. Harries AD, Nyirenda TE, Banerjee

A, Boeree MJ and Salaniponi FM. Tuberculosis in health care workers in Malawi

(1999) Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 93: 32-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0035-9203(99)90170-0 15. Hosoglu S, Tanrikulu AC, Dagli C and Akalin

S. Tuberculosis among health care workers in a short working period (2005) Am J

Infect Control 33: 23-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2004.07.013 16. Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for preventing the transmission

of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in health-care facilities,1994 (1994) MMWR 43: 1-132. 17.

Vries G, ebek MMGG and Weezenbeek

L. Healthcare workers with tuberculosis infected during work (2006) Eur Respir

J 28: 1216-1221.

https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.06.00039906 18.

Koshak

EA and Tawfeeq RZ. The prevalence of positive tuberculin skin reactions at King

Abdulaziz University Hospital, Saudi Arabia (2003) East Mediterr Health J 9:

1034-1041. 19.

https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/tb18_ExecSum_web_4Oct18.pdf 20.

Mazurek

GH and Villarino ME. Guidelines for using the QuantiFERON-TB test for

diagnosing latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection (2003) Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 52: 15-18. 21.

Chan ED, Heifets

L and Iseman MD. Immunologic diagnosis of tuberculosis: A review (2000) Tuberc

Lung Dis 80: 131-140.

https://doi.org/10.1054/tuld.2000.0243 22.

Jackett

PS, Bothamley GH, Batra HV, Mistry A, Young DB et al. Specificity of antibodies

to immunodominant mycobacterial antigens in pulmonary tuberculosis (1988) J

Clin Microbiol 26: 2313-2318. 23.

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00038873.htm 24. Jerant

A, Bannon M and Ritteenhouse S. Identification and management of tuberculosis

(2000) American family physician 61: 2667–2678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2004.07.013 25. Hosoglu S,

Tanrikulu AC, Dagli C and Akalin S. Tuberculosis among health care workers in a

short working period (2005) Am J Infect Control 33: 23-26.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2004.07.013 26.

Demkow

U, Broniarek-Samson B, Filewska M, Lewandowska K, Maciejewski J, et al. Prevalence

of latent tuberculosis infection in health care workers in Poland assessed by

interferon-Gamma whole blood and tuberculin skin test (2008) J Physiol

Pharmacol 6: 209-217. 27.

Harries AD, Nyirenda TE, Banerjee

A, Boeree MJ and Salaniponi FM. Tuberculosis in health care workers in Malawi

(1999) Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 93: 32-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0035-9203(99)90170-0 28. Maciel EL,

Viana MC, Zeitoune RC, Ferreira I, Fregona G, et al. Prevalence and incidence

of mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in nursing students in Vitória,

Espírito Santo (2005) Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 38: 469-472.

https://doi.org/S0037-86822005000600004 29. Alonso-Echanove J, Granich RM,

Laszlo A, Chu G, Borja N, et al. Occupational transmission of mycobacterium

tuberculosis to health care workers in a university hospital in Lima, Peru

(2001) Clin Infect Dis 33: 589-596. https://doi.org/10.1086/321892 30. Barret-Connor

E. The epidemiology of tuberculosis in physicians (1979) JAMA 241: 33-38. 31. Pai M, Gokhale

K, Joshi R Dogra S, Kalantri S, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in

health care workers in rural India: Comparison of a whole-blood interferon

gamma assay with tuberculin skin testing (2005) JAMA 293: 2746-2755. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.22.2746 32. Mori

T, Sakatani M, Yamagishi F Takashima T, Kawabe Y, et al. Specific detection of

tuberculosis infection: An interferongamma-based assay using new antigens

(2004) Am J Respir Crit Care Med 170: 59-64. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0030494 33. Joshi R,

Reingold A L, Menzies D and Pai M. Tuberculosis among health care workers in

low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review (2006) PLoS Med 3: 494.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0030494 34. Naidoo

S and Jinabhai CC. TB in health care workers in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

(2006) Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 10: 676-682. 35. Arcia-Garcia ML, Jiminez-Corona A,

Jiminez-Corona ME, Ferreyra-Reyes L, Martínez K, et al. Factors associated with

tuberculin reactivity in two general hospitals in Mexico (2001) Infect Control

Hosp Epidemiol 22: 88-89. https://doi.org/10.1086/501869 36. Hosoglu S,

Tanrikulu AC, Dagli C, Akalin S. Tuberculosis among health care workers in a

short working period (2005) Am J Infect Control 33: 23-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2004.07.013 37.

Jiamjarasrangsi W, Hirunsuthikul N

and Kamolratanakul P. Tuberculosis among health care workers at King

Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital, 1988-2002 (2005) Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 9:

1253-1258. Faiza

A, Associate professor of internal Medicine, Sanaa University, Yemen, E-mail: faiza.askar@yahoo.com Faiza

A, Khaled A, Mohammed B and Abdalhafed A. Prevalence of Latent Tuberculosis

Infection (LTBI) among health care workers at Al-Thawrah modern general

hospital, Sanaa-Yemen 2016 (2019) Nursing and Health Care 4: 1-5

Prevalence of Latent Tuberculosis Infection (LTBI) among Health Care Workers at Al-Thawrah Modern General Hospital, Sana’a-Yemen 2016

Askar Faiza,

Alaghbari Khaled, Bamashmus Mohammed and Alselwi

Abdalhafed

Abstract

Full-Text

Introduction

Objective

Methods

Results

Discussion

Conclusion

Acknowledgement

References

*Corresponding author

Citation