Research Article :

Jessica Galvan,

Danielle Bordin, Cristina Berger Fadel, Alessandra Martins and Fabiana Bucholdz Teixeira Alves Introduction: Conducting dental consultations during

pregnancy is considered an important challenge in the context of Maternal and

Child Health Policies, as it is surrounded by myths rooted among users and

health professionals. In this sense, it is important to identify barriers and

facilitators to the search for dental assistance in this period, in order to

support strategies that make this practice feasible. Objective: To analyze the search for dental care during high-risk

pregnancies, according to sociodemographic, gestational and health

characteristics. Methods: Observational study with a cross-sectional

design, carried out with high-risk pregnant women referred to a teaching

hospital in southern Brazil, from January to May 2018. Data collection was

performed using an unprecedented structured form and considered as a dependent

variable the search for dental care during pregnancy and as independent

variables sociodemographic, gestational and dental characteristics. Pearson's

chi-square association test and Fisher's exact test were used. Results: To reach the sample of 190

pregnant women at high gestational risk, a total of 230 women considered valid

were approached, counting on the following losses: refusal to participate (n=23),

no answer to any question (n=10), duplicity in participant approach (n=7).

Advanced maternal age (p=0.000) and history of premature birth in previous

pregnancies (p=0.047) were factors associated with a lower frequency of seeking

dental care in the current pregnancy. On the other hand, the habit of dental

consultation prior to the gestational period (p=0.001), the knowledge about the

importance of this monitoring (p=0.050), as well as the safety (p=0.000) in

performing dental prenatal care, were related positively to the search during

pregnancy. Conclusion: Specific

incentive strategies and access to dental prenatal care are necessary to

neutralize barriers that may compromise the search for oral health services

during pregnancy. For this reason, identifying the facilitators and hinders to

the dental service is essential for planning effective actions related to

prenatal care. According to the

Brazilian Ministry of Health, high gestational risk is one that encompasses

pregnancies in which the life or health of the mother-child binomial has a

greater chance of complications, when compared to the average of pregnancies

[1]. Within the scope of public policies in the country, the stratification of

gestational risk is carried out initially in primary health

care,

after confirmation of pregnancy and registration of the pregnant woman, with

subsequent maternal attachment to a specialized reference service, in order to

make the adequate monitoring prenatal care to the specific needs of the

pregnant woman [2]. Despite advances and permanent remodeling of the Unified Health

System (SUS), especially with the creation of Health Care

Networks and the Cegonha Network, instituted to foster the implementation of a

new model of health care for women and children, prenatal care in Brazil still

suffers historical and social influences from the biomedical perspective,

being, often, the approach of pregnant women based on installed problems and

not on preventive practices [3]. The early identification of women with high

gestational risk is fundamental for the assertive guidance of health

professionals and for the woman herself, since it aims at raising awareness of

her condition and health systems, with a view to reduction of maternal and neonatal

morbidity and mortality [4-6]. Gestational risk

is mainly related to maternal age, hypertension and diabetes, conditions that,

in isolation or associated with other factors, can cause the development of oral diseases such

as decreased salivary flow and greater occurrence of periodontal

disease. In this sense, there is also a possible

relationship between maternal periodontal disease and adverse problems during

pregnancy, such as the occurrence of premature birth, identified in recent

systematic reviews but which still lacks conclusive evidence that can confirm

it [7-15]. Although not yet

fully incorporated into the routine of health services, the performance of the

dental surgeon and other professionals must occur in a synergistic manner, especially

with the doctor who accompanies prenatal care,

being relevant for reducing the neglect of self-care of the pregnant [16]. Aware

that dentists' approach to high-risk pregnant women is a relevant theme for the

consolidation of public maternal and child health policies, the objective of

the study is to relate the search for dental care during high-risk pregnancy

with sociodemographic characteristics, gestational and dental. Cross-sectional

observational, quantitative study carried out with high-risk pregnant women

referred to a teaching hospital in southern Brazil that is a reference to

public health for twelve small and medium-sized municipalities, with

comprehensive care by SUS. The study considered all high-risk pregnant women

who underwent medical prenatal care at the hospital, over 18 years old, in the

3rd trimester phase, and who agreed to participate in the research.

The risk stratification recommended by the Ministry of

Health followed [1]. Pregnant women with any acute or

chronic condition that limited their ability to participate in the study were

excluded. Data were collected between January and May 2018. For the sample

calculation, the average number of monthly visits to high-risk

pregnant women in the third trimester of pregnancy (n=100)

was considered, multiplied by the estimated months for collection (n=5), with

an accuracy of 5%, confidence level 95% and design effect 1, for a prevalence

of 27% of pregnant women who received dental care during pregnancy, resulting

in a sample of 190 pregnant women. The imputed prevalence was based on a

previous study of Moimaz et al. [17], with a population of similar characteristics.

To estimate the sample, the Info 7.1.4 software was used. For the

composition of the sample, random stratification of the pregnant women was

performed, alternating the days of information collection, aiming at covering pregnant women from

all the municipalities assigned to the hospital under analysis. As the prenatal

care service is organized on different days of the week, considering that each

day of the week, one or two municipalities are covered, this methodological

strategy was used in order to ensure relative homogeneity as to the number of

pregnant women in each location, according to according to population size. The information

was collected through an individual interview with an unprecedented structured

questionnaire, containing sociodemographic, gestational and dental

characteristics during pregnancy, based on

validated instruments from the Ministry of Health and previous studies [17-21].

The interview was conducted by two researchers trained to gather the necessary

information and answer questions, without influencing the answers and lasted an

average of 10 minutes. The pregnant women were invited to participate in the

research while waiting for the prenatal consultation, being subsequently

directed to a reserved environment inside the hospital itself. A pilot study was

carried out with 40 high-risk pregnant women using the study hospital, and the

data obtained were not part of the sample. After this stage, there was a change

in the approach and vocabulary used, in order to ensure the full understanding

of pregnant women regarding the data collection instrument. The information was

analyzed using descriptive statistics and bivariate analyzes, seeking to

identify the independent associations among the variables investigated. The

significance level of 5% was considered and the association test used was

Pearson's chi-square test and Fisher's exact test. The dependent variable

listed was 'Search for Dental Care during Pregnancy' (considering the current

pregnancy), and as independent variables sociodemographic

characteristics (age, education, family income, marital

status and occupation), gestational (clinical complications during pregnancy

current, number of pregnancies, history of previous pregnancies and maternal

pathologies) and dental (habit of consultation in the pre-pregnancy period,

change in oral hygiene

habits, self-perception of oral changes, self-assessment

of oral health, and knowledge, safety and search for dental care in the current

pregnancy). The research was

approved by the Research Ethics Committee with human beings of the State University

of Ponta Grossa (opinion number 2,364,648; CAAE:

78544717.4.0000.0105, respecting the dictates of resolution 466/12 of the

National Health Council and international standards for research with humans).

The participating pregnant women consented to participate in the research by

signing the Free and Informed Consent Form and the Term of Authorization of

Place for the accomplishment of the research was signed by the academic

director of the teaching hospital authorizing the accomplishment of the

research in the ambulatory of high risk pregnant women. To reach the

sample of 190 pregnant women at high gestational risk, a total of 230 women

considered valid were approached, counting on the following losses: refusal to

participate (n=23), no answer to any question (n=10), duplicity in participant

approach (n=7). The

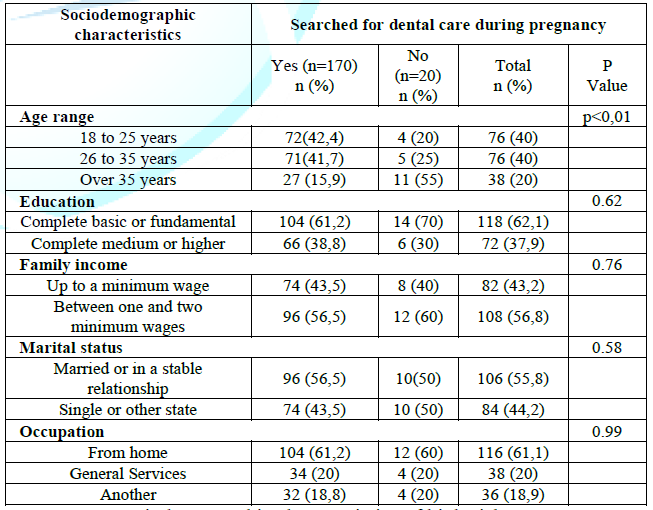

sociodemographic characteristics of the pregnant women were associated to the

‘Search for dental care during pregnancy, with age being the only factor

significantly associated. Pregnant women over the age of 35 were less likely to

seek dental care when compared to the younger age (p<0.005). The search for

dental care was predominant among pregnant women with complete basic or

elementary education, family income between one and two minimum wages, married

or in a stable union and home occupation (Table

1). Table

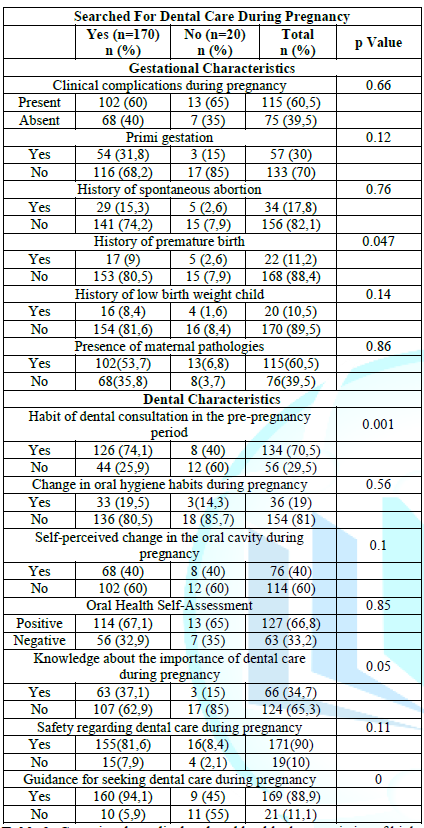

2

shows the association among gestational, medical and oral health

characteristics, with the search for dental care during pregnancy. Regarding to

the investigated gestational variables, there was a statistically significant

association only between pregnant women who did not seek dental care and a

history of premature birth (p=0.047). Among the oral health

characteristics analyzed, pregnant women who claimed to

have the habit of consulting the dental surgeon before pregnancy and pregnant

women who were instructed to seek this professional during pregnancy were

associated with the search for dental care during pregnancy (p=0.001 and 0000,

respectively). Themes such as

access or use of dental services by high-risk pregnant women were not found in

the literature, which highlights the need for studies with this population and

specific themes. The results of the present study showed that pregnant women

over the age of 35 and pregnant women with a history of premature birth were

less likely to seek dental care

during pregnancy. On the other hand, pregnant women who

already had the habit of seeking the dental surgeon before the gestational

period and pregnant women who received this guidance effectively sought dental

care more frequently. It is known that

maternal age has a strong influence on the perinatal medical condition of

pregnant women and their babies, with a higher risk of low birth weight for

children of very young mothers or mothers between 35 and 39 years old and with

a higher risk of mortality for mothers over 40 years of age [22-25]. In addition,

Dias et al. [26], points to a possible relationship among the presence of

adverse results involving high-risk pregnancies with other socioeconomic

contexts, such as low income and low educational level. Although these

parameters seem to act as indicative of health care, education and income, they

were not significantly related to the search for dental care during pregnancy

in the present study. In the context of

oral health, the relationship found between older pregnant women and lower

frequency of seeking dental care suggests advanced maternal age also as a risk

marker for the maintenance or aggravation of oral diseases. The contact with

the dental surgeon during high-risk

pregnancy becomes even more relevant, since preexisting oral

conditions can be exacerbated during the gestational period and are related to

systemic diseases [27-30]. Regarding to

prematurity in the gestational period, although its etiology is multiple,

maternal age over 35 years and the absence of qualified prenatal care are often

identified as risk factors. Despite not completely conclusive and diverse

interactions, which need more robust evidence, also points to the relationship

with periodontal disease as a possible risk factor for the occurrence of

premature birth; low birth weight and pre-eclampsia [12-15,31-33]. Among these

gestational complications, a history of premature birth was the only data

collected that showed a significant relationship with the search for dental

care during pregnancy. Women with no history of preterm birth in a previous

pregnancy sought the dental surgeon in the current pregnancy more frequently,

which may suggest a positive habit of dental consultation during pregnancy by

these women, and consequently the treatment and prevention of periodontal

disease, or even suggest a greater importance they attach to oral health care

during pregnancy. Another finding

of the study was the positive association between the habit prior to pregnancy

to seek the dentist and the maintenance of this practice during the gestational

period. Although the demand for dental services during pregnancy has

traditionally been low and is mainly related to episodes of dental pain,

behavior experts say that behaviors that help in promoting and maintaining

health are generally developed during childhood and adolescence, and maintained

in adulthood [34-36]. In this sense,

access strategies that enable dental care in the pre-conception period are

fundamental, since the lack of routine dental care in the pre-pregnancy period

is pointed out as the most significant predictor of non-receipt of this care

during pregnancy. In the specific case of pregnant women, barriers imposed by

beliefs and myths that dental treatment

should be postponed during pregnancy, coupled with feelings of professional

insecurity act as agents against the search for dental care by pregnant women.

For this reason, oral health education appears as a necessary behavioral

practice to neutralize the fear present among pregnant women, by bringing the

possibilities of dental treatment during the gestational period and

facilitating the understanding of the necessary procedures [37-40]. On the other

hand, the results showed that the guidance given to pregnant women, in the

search for dental care, showed a positive relationship with the frequency with

the dentist, which is relevant to the performance of the health team during the

prenatal period and the insertion of oral health professionals in an

interdisciplinary team. A similar result was found in a study with pregnant

women of habitual risk, in which the incentive to seek dental care and the

referral of the pregnant woman to the dental surgeon during prenatal care were

key factors for the pregnant woman's decision to seek dental care in

pregnancy [41]. Thus, the

insertion of the dental surgeon in prenatal care and the exploration of

characteristics of high-risk pregnant women become essential to control,

prevent and treat perinatal health problems. The early identification of

intraoral changes allows the treatment and prevention of clinical conditions

that can impact the quality of life of the pregnant woman and the baby, and

that can act as risk factors for unfavorable obstetric outcomes [36]. However,

the presence of the dental surgeon in the interdisciplinary prenatal team is

not yet a consolidated reality in several places, however, as a way of raising

awareness, it is suggested both by the team and by the population of pregnant

women when the risk of oral and systemic problems through the adoption of

attitudes favorable to oral health [42]. As limitations of

this study, we highlight the sample's regionality, whose results do not allow

extrapolation, and the specific aspects of cross-sectional surveys and the use

of interviews as a data collection instrument. Another limiting aspect was the

scarcity of research with high-risk pregnant women, which hindered the

discussion of the findings in the light of the literature. Specific

incentive strategies and access to dental prenatal

care

are necessary to neutralize barriers that may compromise the search for oral

health services during pregnancy. For this reason, identifying the facilitators

and hinders to the dental service is essential for planning effective actions

related to prenatal care. It is also concluded that the inclusion of actions

aimed at women during the prenatal period in oral health services, with an

emphasis on health guidance, is of great importance to promote the quality of life

of pregnant women. *Jessica Galvan,

Multiprofessional Residency Program in Neonatology, State University of

Ponta Grossa (UEPG), 199 Street João Pereira de Oliveira, Órfãs, Ponta Grossa,

PR, Brazil, Tel: +5542999807290, E-mail: jegalvan21@gmail.com

*Cristina

Berger Fadel, Department of Dentistry, State

University of Ponta Grossa, Carlos Cavalcanti 4748 Avenue, Block M, Uvaranas

Campus, Ponta Grossa, PR zip code 84030-000, Brazil, E-mail: cbfadel@gmail.com

Galvan J, Bordin D, Fadel CB,

Martins A and Alves FBT. Factors associated to the search for dental care in

high risk pregnancy (2020) Dental Res Manag 4: 66-70. Dental care, Prenatal care, Pregnancy, High riskFactors Associated to the Search for Dental Care in High Risk Pregnancy

Abstract

Full-Text

Introduction

Methods

Results

Discussion

Conclusions

References

Corresponding

authors

Citation

Keywords