Research Article :

Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue

syndrome (ME/CFS), is a chronic and often disabling disease. Although the exact

pathophysiological mechanism of ME/CFS is unknown, immunological abnormalities

may play an important role. Curcumin is an herb with powerful anti-oxidative

and anti-inflammatory properties. Therefore, we hypothesized that curcumin

would have favorable effects on symptomatology in ME/CFS patients. In an open

trial among 65 ME/CFS participants, 6 stopped the use of curcumin because of

side effects and 8 did not complete the end of study questionnaire. Before and

8 weeks after the use of curcumin complexed with phosphatidyl choline-, 500 mg

bid, participants completed the CDC inventory for assessment of Chronic Fatigue

Syndrome. The CDC questions (n=19) were scored and divided into 2 parts: the

first being specific for CFS complaints (n=9), the second being scores of less

specific symptoms (n=10); denoted as CDC other score. Results showed that 8

weeks of curcumin significantly decreased the CDC CFS-related symptom scores

and CDC other scores, especially in patients with mild disease. Conclusion: in

this open-labeled study 8 week curcumin use in a phosphatidyl choline complex

reduced ME/CFS symptomatology, especially in patients with mild disease severity. Curcumin is an herb with powerful

anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory,

anti-mutagenic, and anti-microbial properties [1-9]. Oxidative stress can

lead to chronic inflammation. Curcumin can decrease TNF-α production and can inhibit

inflammatory cytokines. See for extensive reviews the studies of Pulido-Moran

[10-20]. Because of these properties, curcumin has been studied in inflammatory

diseases in lungs, joints, bowels, brains, and the cardiovascular system,

rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, Alzheimers disease, mood

disorders, cancer, diabetes, pain. Although animal Experimental studies are

overwhelmingly positive, there is only limited data from human studies [21-27]. Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

(ME/CFS), is a chronic and often disabling disease. The exact prevalence is

unknown but estimates in the US vary between 836.000 and 2.5 million patients,

in the Netherlands between 20.000 and 80.000 patients. Patients with ME/CFS

have been found to be more functionally impaired than those with other

disabling illnesses [28-30]. Although the exact

pathophysiological mechanism of ME/CFS is unknown, immunological abnormalities

may play an important role. Oxidative stress is increased in ME/CFS patients.

The data on cytokines are contradictory and a recent meta-analysis showed no

overall change for approximately 80 plasma cytokines studied in ME/CFS patients

compared to controls. We previously showed in an open treatment trial that

curcumin has favorable effects on symptomatology in

ME/CFS patients, possibly because of the anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory

properties of curcumin. In the present study we hypothesized that effects in

patient reported outcomes might be dependent on the severity of the disease

[31-37]. Patients with ME/CFS were asked

to participate in the registry and gave informed consent. All fulfilled the

Fukuda criteria for CFS and the ME criteria. Disease severity was scored

according to the ME criteria as mild, moderate, or severe. For this analysis,

patients with moderate and severe disease severity were grouped together and

compared with those who had mild disease [38,39]. Patients were asked to complete

the CDC inventory for assessment of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Dutch language

version, prior to the start of using curcumin and return the questionnaire by

mail or email. After 8 weeks of curcumin use, the same questionnaire was

completed. Prior to the start of curcumin they also completed the SF-36

questionnaire [40-42]. Patients used Curcumin Phytosome (Curcuma

longa extract complexed with phosphatidylcholine; NOW®) 500 mg capsules twice a

day. According to the manufacturer the capsules contained at least 18% (90 mg)

curcuminoids. In total 65 patients

participated. Six patients stopped the use of curcumin because of side effects

(all of gastro-intestinal origin). Eight patients did not return the second

questionnaire despite two reminders. These 14 participants were excluded from

the analysis, leaving 51 participants with complete data. No other treatments

for ME/CFS were used during this study period. No side-effects were reported in

the patients who completed the trial period and returned the second

questionnaire. The work described has been carried out in accordance with The

Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) for

experiments involving humans. The medical ethics committee of the Slotervaart

Hospital, Amsterdam, NL, approved the use of patient data for research (code

U/17.089/P1736). The CFS CDC inventory contains 19

symptom questions and collects information about the presence, frequency, and

intensity of 19 illness-related symptoms during the month preceding the

interview; these symptom questions include all the CFS-defining symptoms.

Perceived frequency of each symptom was rated on a five-point scale (0-4) and

severity or intensity of symptoms was measured on a four-point scale (0-3).

Individual symptom scores were calculated by multiplying the frequency score by

the intensity score. For this purpose the intensity scores were transformed

into equidistant scores (0, 1, 2.5, and 4) before multiplication. This results

in a range of 0–16 for each symptom [40]. The CDC score contained the

summed score of the 19 symptoms. For the purposes of this analysis, we

subdivided the CDC score into 2 parts: the CFS score and the CDC other score.

The CFS score consisted of the 8 CFS defining symptoms namely, post-exertional

fatigue, unrefreshing sleep, problems remembering or concentrating, muscle

aches and pains, joint pains, sore throat, tender lymph nodes and swollen

glands and headaches. In the CFS diagnostic criteria memory and concentration

difficulties are taken as one combined symptom, whereas in the CDC inventory

these 2 symptoms are scored separately. Therefore, for the CFS scores 9

symptoms were summed. The 10 remaining CDC questions that were not related to

the CFS score were also summed and labeled as CDC-Other score. The CDC other

score is composed of the symptoms: diarrhea, fever,

chills, sleep problems, nausea, stomach or abdominal pain, sinus or nasal

problems, shortness of breath, light hypersensitivity and

depression. Moreover, in the second, post-curcumin

questionnaire, we asked how you rate your global physical and mental condition

after using curcumin: 0: strongly deteriorated, 1: mildly deteriorated, 2: no

change, 3: mildly improved and 4: strongly improved. One patient reported mild deterioration

after curcumin use. For the chi-square analysis this Patient was added to the

no change group. Similarly, the two improvement answers were also analyzed

together. Scores were tested for normal

distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test in SPSS (IBM SPSS version 21).

Normally distributed data are presented as mean (SD) and non-normally

distributed data as median (IQR). Data were compared with Students

test for paired and unpaired data, and with the Mann-Whitney U test for

non-normally distributed data, where appropriate. Chi square analysis was

performed on the distribution of the Patient Reported Outcome Measure (PROM):

yes or no change in physical and mental condition after curcumin use. A p value

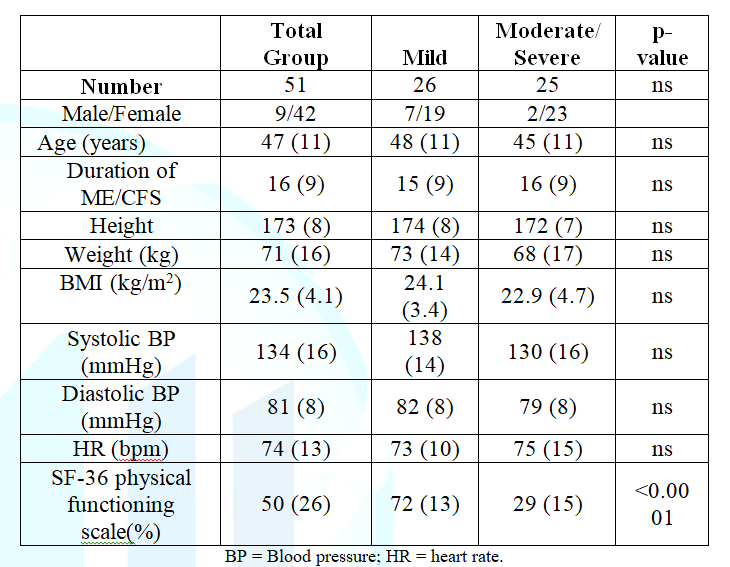

<0.05 was considered significantly different. Table

1 shows the demographic data for the 51 participants

analyzed. Forty-two females and 9 males were included. The mean disease

duration was 16 (9) years, and the mean age was 47 (11) years. Except for

height and weight, there were no differences between males and females (data

not shown). According to the ME criteria 26

patients were graded as mild and 25 as moderate to severe (15 moderate and 10

severe patients). Table 1 also shows the baseline data for the mild vs the

combined moderate and severe group. No differences were present except for the

SF-36 physical functioning scale; as expected, mildly affected patients had a

higher physical functioning scale than the moderately and severely affected patients

p<0.0001. Table 1:

Baseline characteristics of the total group and of the mild vs the moderate to

severe ME/CFS patients. Table

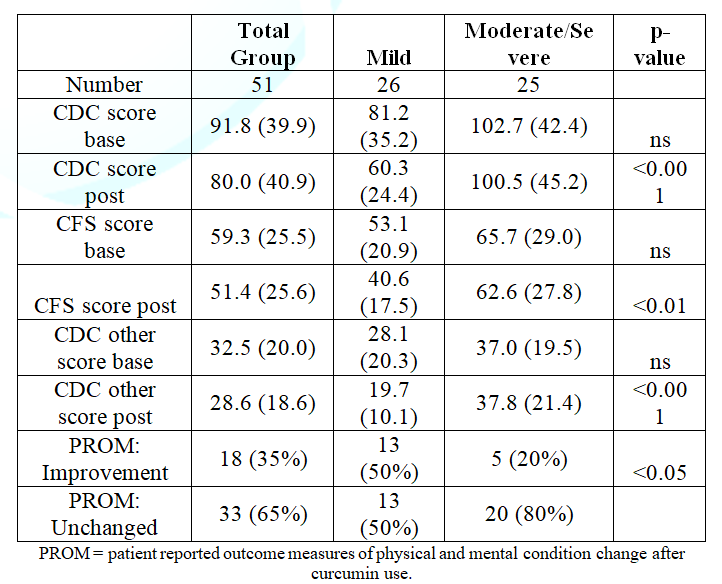

2 shows the CDC inventory score results and the PROM:

the change in physical and mental condition after curcumin use. Table 2:

CDC, CFS and CDC other scores for mild vs moderate/severe ME/CFS patients. Figure

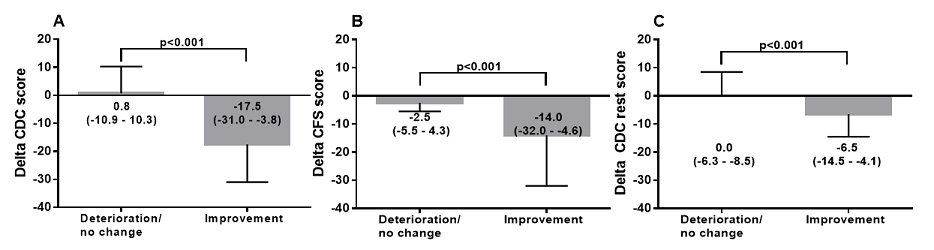

1 shows the data of the PROM: unchanged and improved

physical and mental improvement versus the change in the total CDC score (post

curcumin use minus pre curcumin use). Patients with the PROM: unchanged showed

a significantly lower change in the total CDC score compared to the change in

patients reporting improvement Table 2 also shows the

differences between patients with mild disease vs moderate and severe disease.

Baseline CDC, CFS and CDC other scores were all higher in the mildly affected

patients versus the moderate and severe patients, but did not reach statistical

significance. After 8 weeks of curcumin use, both the total CDC scores, the CFS

scores and CDC-other scores were significantly lower (p<0.001, p<0.01 and

p<0.001 respectively), compared to pre-curcumin use in

the mild ME/CFS group, but were not different in the moderate to severe ME/CFS

group. Figure 1 show the changes in CDC,

CFS and CDC other scores with respect to the patient reported outcome of

neutral/deterioration or improvement. Figure

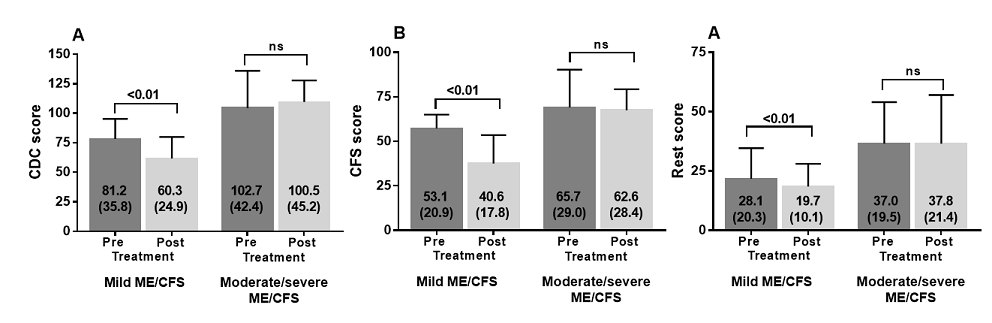

2 shows the pre- and post-treatment values of the three scores in both mild

versus moderate to severe ME/CFS patients. The CDC, CFS, and CDC-other scores

post curcumin use were all significantly lower in the mild ME/CFS group, whereas

not different in the moderate to severe ME/CFS group.In the group with mild

disease (n=26) 13 reported improvement in the global physical and mental

condition, 13 reported no change. In the moderate/severe group, 5 reported

improvement and 20 reported no change (p<0.05). Figure 2:

CDC score pre and post treatment in mild and moderate/severe ME/CFS patients

(panel A), CFS score pre and post treatment in mild and moderate/severe ME/CFS

patients (panel B) and CDC rest score pre and post treatment in mild and

moderate/severe ME/CFS patients (panel C). To the best of our knowledge,

this is the first study that indicates that curcumin use has a positive effect

on symptoms in ME/CFS patients as assessed by the CDC inventory for CFS, and

that those with more severe disease are less likely than those with mild

disease to report improvement. In 2018 we published the first open label

results in ME/CFS patients, showing curcumin might be a

supplement to be prescribed in ME/CFS patients(van Campen 2018). In this larger

group we investigated whether there was a relation between disease severity and

efficacy. Symptoms in ME/CFS include a

perpetual flu-like state, sore throats, tender/swollen lymph nodes, muscle

pain, achy joints without swelling or redness, headaches, chills, feverishness

and sensitivities to foods, odors, and medications, which are all indicative of

inflammation [28].

As increased oxidative stress and altered cytokine patterns have been

demonstrated in ME/CFS, it is likely that curcumin exerts its beneficial

effects by the anti-oxidative

and anti-inflammatory properties.

However, the exact mode of action of curcumin needs to be determined. Moreover,

ME/CFS is considered to be in part a neuro-inflammatory disease. As curcumin

passes the blood-brain barrier it is therefore tempting to assign the positive

effects also to an anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory effect in the brain

[1-6,31-36,43-49]. Overall, the effect of curcumin

use on ME/CFS symptoms is limited: for the total ME/CFS patient group the total

CDC score decreased from 91.8 (39.9) to 80.0 (40.9), a mean reduction of 12%

(data not shown). The limited efficacy is also obvious from the PROM: change in

physical and mental condition after curcumin use. Thirty-five percent of

patients reported improvement in their physical and mental condition after

curcumin use. The finding that the PROM: improved is associated with a larger

decrease in the total CDC score strengthens the validity of this study. A difference in treatment

efficacy was found between patients with mild disease versus moderate or severe

disease. In the latter group curcumin was less effective. This observation is

not uncommon in other diseases. For example, in a study using a bronchodilator for

COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease), the medication under study was

less effective in severe COPD vs moderate COPD [50].The reduced efficacy in the

moderate to severe ME/CFS patient may be related to a higher load of

inflammation in this patient group in combination with the low bioavailability

of curcumin. In the unprocessed form the uptake of curcumin is very low. To

improve uptake, encapsulation in liposomes, polymeric nanoparticles,

cyclodextrin encapsulation, lipid complexes, phosphatidylcholine complexes or

polymer-curcumin complexes have been developed, all of which increase the

activity and bioavailability. In a study the absorption of a standardized

curcuminoid mixture and its lecithin formulation was compared [19,51,52]. Total curcuminoid absorption was

about 29-fold higher than for its corresponding unformulated curcuminoid

mixture, but plasma concentrations were still significantly lower than those

required for the inhibition of most anti-inflammatory targets of curcumin.

Remarkably, the phospholipid formulation increased the absorption of

demethoxylated curcuminoid much more than that of curcumin, being a more potent

analogue in many in vitro anti-inflammatory assays. It is possible that an even

higher dose or an increased bioavailability of curcumin and or demethoxylated

curcuminoid may be more effective in moderate to severe ME/CFS patients. These

needs to be studied and further efforts to increase bioavailability and the

clinical effects of the different curcuminoid components are also needed. An interesting finding was that

not only the CFS score decreased significantly in the mild disease group, but

also the CFS-other scores. Some of these symptoms might be related to

inflammation and therefore might respond to curcumin treatment. A larger study

is needed to address the question regarding which specific symptoms are

ameliorated by curcumin. Unexpectedly, a relatively high number of ME/CFS

patients (n=6, 10%) stopped the use of curcumin because of side effects. The

explanation may be that multiple chemical sensitivities are prevalent in ME/CFS

patients. In the study of Brown and Jason, the co-occurrence was almost 24%

[53]. It is unclear whether the drug itself or added excipients cause the

intolerance. The patients completing the study reported no side effects due to

this supplement.The meta-analysis of reported nausea and gastro-intestinal side

effects to be the main reported adverse events. They also reported studies no

showing any side effects. The ME/CFS patients with side effects found these

severe enough to stop the treatment [54]. This study was an open-label

study, without a placebo arm. Some patients (n=8) did not return the first or

second questionnaire, possibly leading to bias. A number of patients in the

outpatient clinic admitted that they had difficulties with completing the

questionnaire. This is most probably due to their memory and concentration

problems, a disabling feature of the disease. A supervised completion approach

may overcome this problem. The meta-analysis of table 1 shows an overview of

trials in which there were different doses and durations of treatment, varying

from single dose interventions up to treatment durations of 22 months [54]. We

chose – empirically in the ME/CFS patient group – for treatment duration of 8

weeks. If a positive response is not present after 8 weeks, the likelihood that

improvement will occur with longer duration is considered to be low. As

patients are not reimbursed for these supplements, we elected to stop treatment

after a few months. Further study would determine whether a longer duration

might increase the percentage of responders. In summary, in this open-labeled

study, 8 weeks of curcumin use in a phosphatidylcholine complex reduced ME/CFS symptomatology,

especially in patients with mild disease, whereas it did not significantly

change symptoms in moderate and severe patients. A randomized

placebo-controlled, larger study is warranted to assess its efficacy in ME/CFS patients. The raw data supporting the

conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without

undue reservation, to any qualified researcher. We acknowledge Prof PC Rowe for a

critical review of the paper. 1.

Joe

B and Lokesh BR. Role of capsaicin, curcumin and dietary n-3 fatty acids in

lowering the generation of reactive oxygen species in rat peritoneal

macrophages (1994) Biochim Biophys Acta 1224: 255-263. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-4889(94)90198-8 2.

Reddy

A C and B R Lokesh. Effect of dietary turmeric (Curcuma longa) on iron-induced

lipid peroxidation in the rat liver (1994) Food Chem Toxicol 32: 279-283. https://doi.org/10.1016/0278-6915(94)90201-1 3.

Kang

J, Chen J, Shi Y, Jia J and Zhang Y. Curcumin-induced histone hypoacetylation:

the role of reactive oxygen species (2005) Biochem Pharmacol 69: 1205-1213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2005.01.014 4.

Jeong

GS, Oh GS, Pae HO, Jeong SO, Kim YC et al. Comparative effects of curcuminoids

on endothelial heme oxygenase-1 expression: ortho-methoxy groups are essential

to enhance heme oxygenase activity and protection (2006) Exp Mol Med 38:

393-400. https://doi.org/10.1038/emm.2006.46 5.

Abdel-Daim

MM and Abdou RH. Protective Effects of Diallyl Sulfide and Curcumin Separately

against Thallium-Induced Toxicity in Rats (2015) Cell J 17: 379-388. 6.

Joe

B, Vijaykumar M and Lokesh B R. Biological properties of curcumin-cellular and

molecular mechanisms of action (2004) Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 44: 97-111. 7. Wright

LE, Frye JB, Gorti B, Timmermann BN and Funk JL. Bioactivity of

turmeric-derived curcuminoids and related metabolites in breast cancer (2013)

Curr Pharm Des 19: 6218-6225. https://doi.org/10.2174/1381612811319340013 8.

Mahady

GB, Pendland SL, Yun G and Lu ZZ. Turmeric (Curcuma longa) and curcumin inhibit

the growth of Helicobacter pylori, a group 1 carcinogen (2002) Anticancer Res

22: 4179-4181. 9.

Reddy

RC, Vatsala PG, Keshamouni VG, Padmanaban G and Rangarajan PN. Curcumin for

malaria therapy (2005) Biochem Biophys Res Commun 326: 472-474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.051 10.

Sethi

G, Sung B and Aggarwal BB. Nuclear factor-kappaB activation: from bench to

bedside (2008) Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 233: 21-31. https://doi.org/10.3181/0707-mr-196 11. Reuter

S, Gupta SC, Chaturvedi MM and Aggarwal BB. Oxidative stress, inflammation, and

cancer: how are they linked? (2010) Free Radic Biol Med 49: 1603-1616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.09.006 12.

Cho

JW, Lee KS and Kim CW. Curcumin attenuates the expression of IL-1beta, IL-6,

and TNF-alpha as well as cyclin E in TNF-alpha-treated HaCaT cells; NF-kappaB

and MAPKs as potential upstream targets (2007) Int J Mol Med 19: 469-474. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijmm.19.3.469 13.

Huang

CZ, Huang WZ, Zhang G and Tang DL. In vivo study on the effects of curcumin on

the expression profiles of anti-tumour genes (VEGF, CyclinD1 and CDK4) in liver

of rats injected with DEN (2013) Mol Biol Rep 40: 5825-5831. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-013-2688-y 14. Li

R, Wang Y, Liu Y, Chen Q, Fu W, et al. Curcumin inhibits transforming growth

factor-beta1-induced EMT via PPARgamma pathway, not Smad pathway in renal

tubular epithelial cells (2013) PLoS One 8. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0058848 15.

Anthwal

A, Thakur BK, Rawat MS, Rawat DS, Tyagi AK, et al. Synthesis, characterization

and in vitro anticancer activity of C-5 curcumin analogues with potential to

inhibit TNF-alpha-induced NF-kappaB activation (2014) Biomed Res Int 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/524161 16. Nieto

CI, Cabildo MP, Cornago MP, Sanz D, Claramunt RM, et al. Fluorination Effects

on NOS Inhibitory Activity of Pyrazoles Related to Curcumin (2015) Molecules

20: 15643-15665. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules200915643 17.

Paulino

N, Paulino AS, Diniz SN, de Mendonca S, Goncalves ID, et al. Evaluation of the

anti-inflammatory action of curcumin analog (DM1): Effect on iNOS and COX-2

gene expression and autophagy pathways (2016) Bioorg Med Chem 24: 1927-1935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2016.03.024 18.

de

Porras RV, Bystrup S, Martinez-Cardus A, Pluvinet R, Sumoy L, et al. Curcumin

mediates oxaliplatin-acquired resistance reversion in colorectal cancer cell

lines through modulation of CXC-Chemokine/NF-kappaB signalling pathway (2016)

Sci Rep 6. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24675 19.

Pulido-Moran

M, Moreno-Fernandez J, Ramirez-Tortosa C and Ramirez-Tortosa C Curcumin and

Health (2016) Molecules 21: 264. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21030264 20.

Pari

L, Tewas D and Eckel J. Role of curcumin in health and disease (2008) Arch

Physiol Biochem 114: 127-149. 21.

Akazawa

N, Choi Y, Miyaki A, Tanabe Y, Sugawara J, Ajisaka R and Maeda S. Curcumin

ingestion and exercise training improve vascular endothelial function in

postmenopausal women (2012) Nutr Res 32: 795-799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nutres.2012.09.002 22. Panahi

Y, Rahimnia AR, Sharafi M, Alishiri G,Saburi A et al. Curcuminoid treatment for

knee osteoarthritis: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial (2014)

Phytother Res 28: 1625-1631. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.5174 23. Ahn

JK, Kim S, Hwang J, Kim J, Lee YS et al. Metabolomic Elucidation of the Effects

of Curcumin on Fibroblast-Like Synoviocytes in Rheumatoid Arthritis (2015) PLoS

One 10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0145539 24.

Lang

A, Salomon N, Wu JCY, Kopylov U, Lahat A et al. Curcumin in combination with

mesalamine induces remission in patients with mild-to-moderate ulcerative

colitis in a randomized controlled trial (2015) Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 13:

1444-1449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2015.02.019 25.

Yu

JJ, Pei LB, Zhang Y, Wen ZY and Yang JL. Chronic supplementation of curcumin

enhances the efficacy of antidepressants in major depressive disorder: a

randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study (2015) J Clin

Psychopharmacol 35: 406-410. https://doi.org/10.1097/jcp.0000000000000352 26.

Rainey-Smith

SR, Brown BM, Sohrabi HR, Shah T and Goozee KG. et al. Curcumin and cognition:

a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind study of community-dwelling

older adults (2016) Br J Nutr 115: 2106-2113. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114516001203 27.

Tenero

L, Piazza M, Zanoni L, Bodini A, Peroni D, et al. Antioxidant supplementation

and exhaled nitric oxide in children with asthma (2016) Allergy Asthma Proc 37:

8-13. https://doi.org/10.2500/aap.2016.37.3920 28.

Institute

of Medicine. Beyond mayalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome:

redefining an illness (2015) The National Academies Press, Washington DC,

United States. 29.

Jason

LA and Richman JA. How science can stigmatize: The case of chronic fatigue

syndrome (2008) J Chronic Fatigue Syndrome 53: 1195–1219. https://doi.org/10.3109/10573320802092146 30.

Twisk

FN. The status of and future research into Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: the need of accurate diagnosis, objective assessment

and acknowledging biological and clinical subgroups (2014) Front Physiol 5:

109. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2014.00109

31.

Jason

L, Sorenson M, Sebally K, Alkazemi D, Lerch A, et al. Increased HDAC in

association with decreased plasma cortisol in older adults with chronic fatigue

syndrome. (2011) Brain Behav Immun. 32.

Morris

G, Anderson G, Dean O, Berk M and Galecki P et al. The glutathione system: a

new drug target in neuroimmune disorders (2014) Mol Neurobiol 50: 1059-1084. 33.

Nijs

J, Nees A, Paul L, De Kooning M, Ickmans K. et al. Altered immune response to

exercise in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: a

systematic literature review. Exerc Immunol Rev 20: 94-116. 34.

Maes,

Bosmans M E and Kubera M. Increased expression of activation antigens on CD8+ T

lymphocytes in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: inverse

associations with lowered CD19+ expression and CD4+/CD8+ ratio, but no

associations with (auto)immune, leaky gut, oxidative and nitrosative stress

biomarkers (2015) Neuro Endocrinol Lett 36: 439-446. 35.

Morris

G, Berk M, Walder K and Maes M. Central pathways causing fatigue in neuro

inflammatory and autoimmune illnesses (2015) BMC Med 13: 28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-014-0259-2 36.

Blundell

S, Ray KK, Buckland M and White PD. Chronic fatigue syndrome and circulating

cytokines: A systematic review (2015) Brain Behav Immun 50: 186-195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2015.07.004 37 van

Campen CLMCRKV, F.C. The effect of Curcumin on patients with Chronic Fatigue

Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis: an open label study (2018) Int J Clinical

Medicine 9: 356-366. https://doi.org/10.4236/ijcm.2018.95031 38.

Fukuda

K, Straus SE, Hickie I, Sharpe MC, Dobbins JG et al. The chronic fatigue syndrome:

a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic

Fatigue Syndrome Study Group (1994) Ann Intern Med 121: 953-959. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-121-12-199412150-00009 39. Carruthers

BM, van de Sande MI, DE Meirleir KL, Klimas NG, Broderick G, et al. Myalgic

encephalomyelitis: International Consensus Criteria (2018) J Intern Med 270:

327-338. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics9010001 40. Wagner

DR, Nisenbaum C, Heim JF, Jones ER, Unger et al. Psychometric properties of the

CDC symptom inventory for assessment of chronic fatigue syndrome (2005) Popul

Health Metr 3: 8. http://doi.org/10.1186/1478-7954-3-8 41.

Vermeulen

RC. Translation and validation of the dutch language version of the CDC symptom

inventory for assessment of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) (2006) Popul Health

Metr 4: 12. http://doi.org/10.1186/1478-7954-4-12 42.

Viehoff

PB, van Genderen FR and Wittink H. Upper limb lymphedema 27 (ULL27): Dutch

translation and validation of an illness-specific health-related quality of

life questionnaire for patients with upper limb lymphedema (2008) Lymphology

41: 131-138. 43.

Hornig

M, Montoya JG, Klimas NG, Levine S, Felsenstein D, et al. Distinct plasma

immune signatures in ME/CFS are present early in the course of illness (2015)

Sci Adv 1. http://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1400121 44.

Hornig

M, Gottschalk G, Peterson DL, Knox KK, Schultzm AF, et al. Cytokine network

analysis of cerebrospinal fluid in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue

syndrome (2016) Mol Psychiatry 21: 261-269. http://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2015.29 45. Landi

AD, Broadhurst SD, Vernon DL, Tyrrell et al. Reductions in circulating levels

of IL-16, IL-7 and VEGF-A in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome

(2016) Cytokine 78: 27-36. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2015.11.018 46.

Russell

L,Broderick G, Taylor R, Fernandes H, Harvey J, et al. Illness progression in

chronic fatigue syndrome: a shifting immune baseline (2016)BMC Immunol 17: 3. http://doi.org/10.1186/s12865-016-0142-3 47.

Nakatomi

Y, Mizuno K, Ishii A, Wada Y, Tanaka M, et al. Neuroinflammation in Patients

with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis: An 11C-(R)-PK11195 PET

Study (2014) J Nucl Med 55: 945-950. http://dx.doi.org/10.2967/jnumed.113.131045 48.

Morris,

G., M. Berk, P. Galecki, K. Walder and M. Maes. The neuro-immune

pathophysiology of central and peripheral fatigue in systemic

immune-inflammatory and neuro-immune diseases (2016) Mol Neurobiol 53:

1195-1219. http://doi.org/10.1007/s12035-015-9090-9 49.

Ryu

EK, Choe YS, Lee KH, Choi Y and Kim BT. Curcumin and dehydrozingerone

derivatives: Synthesis, radiolabeling, and evaluation for beta-amyloid plaque

imaging (2006) J Med Chem 49: 6111-6119. http://doi.org/10.1021/jm0607193 50.

Chapman

KR, Bateman ED, Chen H, Hu H, Fogel R, et al. QVA149 improves lung function,

dyspnea, and health status independent of previously prescribed medications and

copd severity: a subgroup analysis from the SHINE and ILLUMINATE studies (2015)

Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis 2: 48-60. http://doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.2.1.2014.0140 51.

Prasad

S, Tyagi AK and Aggarwal BB. Recent developments in delivery, bioavailability,

absorption and metabolism of curcumin: The golden pigment from golden spice (2014)

Cancer Res Treat 46: 2-18. http://doi.org/10.4143/crt.2014.46.1.2 52. Cuomo

J, Appendino G, Dern AS, Schneider E, McKinnon TP, et al. Comparative

absorption of a standardized curcuminoid mixture and its lecithin formulation

(2011) J Nat Prod 74: 664-669. http://doi.org/10.1021/np1007262 53. Brown

MM and Jason LA. Functioning in individuals with chronic fatigue syndrome:

increased impairment with co-occurring multiple chemical sensitivity and

fibromyalgia (2007) Dyn Med 6: 9. http://doi.org/10.1186/1476-5918-6-6 Gupta SC, Patchva S and Aggarwal BB. Therapeutic

roles of curcumin: lessons learned from clinical trials (2013) AAPS J 15:

195-218. http://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-012-9432-8 54.

Gupta

SC, Patchva S and Aggarwal BB. Therapeutic roles of curcumin: lessons learned

from clinical trials (2013) AAPS J 15: 195-218. http://doi.org/10.1208/s12248-012-9432-8 *Corresponding

author C

(Linda) MC van Campen, Department of Cardiology, Stichting Cardiozorg,

Hoofddorp, Netherlands, E-mail: info@stichtingcardiozorg.nl Citation Campen

CMCV and Visser FC. The effect of curcumin in patients with chronic fatigue

syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: disparate responses in different disease

severities (2019) Pharmacovigil and Pharmacoepi 2: 22-27. Curcumin, Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic

Fatigue Syndrome, Disease severity, CDC score, Fukuda score, R and 36

questionnaire.The Effect of Curcumin in Patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (or) Myalgic Encephalomyelitis Disparate Responses in Different Disease Severities

C(Linda) MC van

Campen*and Frans C Visser

Abstract

Full-Text

Introduction

Patients

and Methods

Data

analysis

Statistical

Analysis

Results

Discussion

Limitations

Conclusion

Data

Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

Keywords