Research Article :

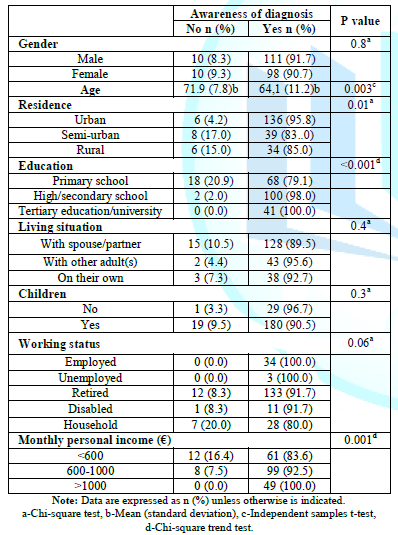

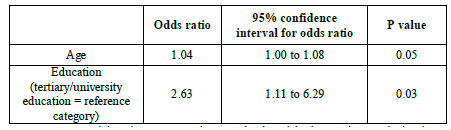

Despoina G Alamanou, Konstantinos Giakoumidakis, Dimosthenis G Theodosiadis, Nikolaos V Fotos, Elissavet Patiraki and Hero Brokalaki Objective: In Greece, the old phenomenon of hiding cancer diagnosis and depriving cancer patients of their right to participate in decision-making remains a reality. The aim of this study was to assess the decision-making preferences of Greek cancer patients and their awareness of diagnosis. Methods: It was a cross-sectional study. The sample consisted of 229 adult Greek patients diagnosed with cancer, attending the oncology outpatient department (outpatients) or being hospitalized (inpatients), in one general hospital in Athens. Patients who were aware of cancer diagnosis (n=209) were administered at the Control Preference Scale (CPS), a tool, designed to elicit decision-making preferences. The IBM SPSS program, version 21.0 was used for statistical analysis. Results: One hundred and one patients (52.8%) were males. The mean [±standard deviation (SD)] age was 64.8 (±11.2) years. The vast majority of patients knew they suffered from cancer (n=209, 91.3%). Older patients (p=0.003), those who lived in suburbs of the city (p=0.01), those who had lower educational level (p=0.001), those with lower personal income (p=0.001) and shorter disease duration (p=0.001) stated that were unaware of cancer diagnosis. Seventy five (36.2%) patients chose the shared-decision role in decision-making procedures. Lower age (OR 1.04, 95%, CI: 1.00-1.08, p= 0.05) and higher education level (OR 2, 63, 95%, CI: 1.11-6.29, p=0.03) were significantly associated with the preference of patients to actively participate in decision-making regarding treatment. Conclusions: Although Greek cancer patients are aware of cancer diagnosis and treatment, nowadays, they still seem to hesitate in playing a more active role in the decision-making procedures, which portrays the impact of the dominating paternalistic model of doctor-patient relationship in the Greek medical encounter. Human

deaths due to cancer have risen sharply, in recent years. Cancer

is one of the most important causes of morbidity and mortality, worldwide, with

nearly 14 million new cases in 2012 [1]. It, also, remains the second leading

cause of death in the world and is responsible for 8.8 million deaths in 2015 [2].

In Greece, cancer is the second leading cause of death and accounts for about

25,000 deaths a year, according to the latest measurements [3]. Diagnosis

of cancer is likely to cause uncertainty and anxiety to patients, emotions that

can be eliminated by providing timely and valid information regarding

diagnosis, prognosis and treatment options. Patients’

awareness of cancer diagnosis and integrated communication with healthcare

professionals are found to be essential for the effective management of the

disease, as well as, the reduction of emotional transitions, improved patients’

quality of life and communication with family members [4-8]. Although, studies

from different countries support the fact that the majority of patients with

cancer need to be well informed about diagnosis and cancer treatment and more

active in the decision-making process, there are still many cancer patients

unaware of their true diagnosis, worldwide, an attitude that is considered

acceptable in many societies [9-14]. Particular emphasis has also been given in

recent decades on patients’ autonomy and their involvement in decisions

regarding treatment [15-16]. Patients’

roles in treatment decision making can differ from playing a passive role,

where all decision are made by the physician, through sharing role, to an

active role, in which patients decide themselves about treatment. In the United

States, National health organizations Recommend the inclusion of patients in

decision-making procedures [8,17]. However, researches support that patient’s

wish to more information and participation in decision making is personalized,

may change through time and can be influenced by social, economic and cultural

factors, while other studies result that patients wishes are often

underestimated by healthcare professional for various reasons [2,5,16,18-21]. The

latest international literature review shows that cancer

patients are more active than ever in the decision-making process. Specifically,

75% of cancer patients with hematological malignancies chose the shared

decision-making according to a recent study in Netherlands. Also, in a study in

USA the majority (53%) of the 119 Hispanic American patients preferred shared

decision-making with their doctor, while only 7,6% had a passive

decision-making style [22,23]. In

Greece, paternalism

is not challenged yet and the consumerist model of health care is not strongly

developed [6]. In recent years, choices of cancer treatment are discussed with

some patients, depending on factors such as educational level, age and health

status, however, Greek physicians often decide on their own the most

appropriate treatment, without having informed the patient first about the

disease and the available treatment options. In 2005, Greek general

practitioners reported that heavy workloads and lack of time are responsible

for incomplete information and promotion of counseling to cancer patients [24]. Consequently,

the aim of this study was to evaluate Greek cancer patients’ awareness of

diagnosis, nowadays, and assess their decision-making preferences regarding

treatment. Very few studies have been conducted in Greece regarding awareness

of cancer diagnosis, with the majority of them being conducted in the previous

decade and only two studies have been carried out regarding decision-making

preferences among Greek cancer patients [6,16,25-27]. Study

Design and Participants It

was a cross-sectional study, conducted in a large general public hospital of Athens.

316 cancer patients were collectively treated in the pathology

clinics and the outpatient department of the study hospital, from January 2013

to August 2014. The inclusion criteria used were The

exclusion criteria used were The

first five exclusion criteria were used because their existence could affect

patients’ consciousness and perception during the interview but also their

answers regarding their preferences on their role in treatment decisions of the

316 patients, 21 had an individual history of psychiatric

disease, 46 patients had Alzheimer's disease or a form of dementia and 13

patients had a co-existing life-threatening disease (5 patients had end-stage

heart failure and 8 patients had chronic renal failure under hemodialysis). According

to the inclusion criteria, 236 patients could have been admitted to the study.

Out of those patients, 229 agreed to participate in the study (response rate

97.03%). The sixth exclusion criterion was used subsequently for the admission

at the Control Preference Scale tool. The final sample of patients that

completed the CPS-Greek edition questionnaire was 209. Collection

of Data and Measures Demographic

data, diagnosis and clinical characteristics were obtained by patients’ medical

records review. Adequate data were collected by means of semi structured

interviews. The Control Preference Scale (CPS) instrument was used in this

study for the assessment of patients’ decision-making preferences. Patients

were evaluated as to whether they had knowledge of their diagnosis and what

this was through interview. Those who knew their diagnosis was cancer (n=209)

were administered to the CPS tool. The

CPS created by Degner et al. [28] is an assessment tool which measures the

decision-making preferences of cancer patients [29]. It is a clinically

relevant, easy-to-administer, reliable and valid measure of roles (preferred

and actual) in decision making on health care issues among cancer patients [30].

It consists of five cards (A to E), each describing a potential role of the

patient in relation to the physician, whenever a decision about treatment is

made. Every card has a statement that describes the role and is illustrated by

a cartoon in order to assist patients of lower literacy level to understand the

meaning. The roles range from (A) the patient being the primary decision maker,

(C) shared decision making, to (E) patient being completely passive to the

physician’s decisions. In

this study, the cards were presented to each patient who was asked to choose

the one that was closer to his/her preferences in a hypothetical scenario of a

consultation with their oncologist, when a decision about treatment must be

made. In this way, patients felt free to choose the role they really prefer to

play in the decision making process, without worrying about their physician’s

opinion. The CPS was translated from English to Greek by Almyroudi et al. [16].

Ethical approval was obtained from the research team that conducted the Greek

translation for the use of the CPS-Greek edition questionnaire. Ethics A

written authorization was obtained from the Ethics Committee and the Scientific

Council of the hospital that was chosen for the study. Patients were invited to

participate in the study and were then provided with additional information

about the research. Prior to the interview, patients who were recruited read

and signed information consent form. The research was conducted with respect to

the patients and the confidentiality of the collected data in accordance with

the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. Statistical

Analysis Continuous

variables are presented with mean and Standard Deviation (SD) or with median

and Interquartile Range (IQR). Qualitative variables are presented with

absolute and relative frequencies. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and graphs

(histograms and normal Q-Q plots) were used to test the normality of the

distribution of the continuous variables. Demographic and clinical

characteristics were independent variables while the role patients prefer

to play in the decision-making process was the dependent dichotomous variable. Bivariate

analyses between demographic and clinical characteristics and the role patients

prefer to play in the decision-making process included chi-square test,

chi-square trend test, independent samples

t-test and Mann-Whitney test. We used chi-square test in case of categorical

demographic and clinical characteristics and chi-square trend test in case of

ordinal variables. Also, we used independent samples t-test in case of

continuous variables that followed normal distribution and Mann-Whitney test in

case of continuous variables that did not follow normal distribution.

Demographic and clinical characteristics with p<0.20 in bivariate analyses,

were entered into the backward stepwise multivariate logistic regression analysis

with the role patients prefer to play in the decision-making process as the

dependent variable. Multivariate

analysis was used to control potential confounding variables. Criteria for

entry and removal of variables were based on the likelihood ratio test, with

enter and remove limits set at p<0.05 and p>0.05. We estimated adjusted

odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals for the predictive factors related to

the role patients prefer to play in the decision-making process. All tests of

statistical significance were two-tailed, and P values of less than 0.05 were

considered significant. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS) program,

version 21.0. (IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version

21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) was used for statistical analysis. Sample

Description There

were no complaints regarding the time of the completion and understanding of

the questionnaire. Participants were mostly male (n=121), with an average age

64.8 years (SD=11.2). Most of the patients (n=102) were high/secondary school

graduates and 46.7% of them (n=107) had a monthly personal income of 600-1.000€.

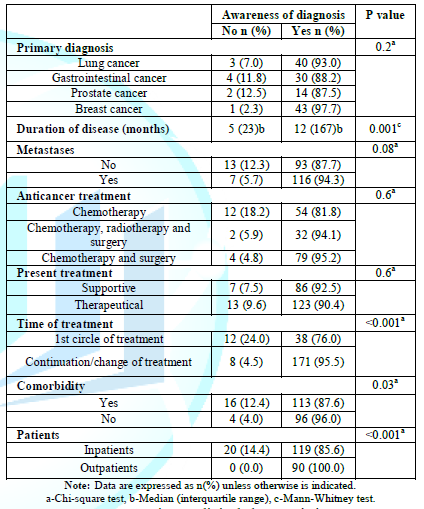

Nearly one fifth of the patients (19.2%) were diagnosed with breast cancer and

18.8% (n=43) with lung

cancer. The median duration of their Diagnose was 22.5 months (IQR: 1-128,

SD: 28.3). Almost half patients (n=106) had no metastatic cancer, while 28.8%

(n=66) of patients had undergone chemotherapy. Most of the participants were

under therapeutical

treatment (n=136), while 40.6% were under supportive treatment. Patients'

demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1 and 2. Awareness

of Diagnosis As

shown in Table 1, the vast majority (91.3%) of study patients were aware of

their diagnosis being cancer. However, 20 patients reported that they did not

know their diagnosis. The mean age of patients who knew they suffer from cancer

was statistically significant lower than those who did not know (64.1 years

versus 71.9, p=0.003). Patients living in an urban area were significantly more

likely to know their diagnosis, compared to patients living in a semi-rural and

rural area (p=0.01). Higher educational level was statistical significantly

related to the patients’ knowledge of cancer diagnosis (p<0.001). Increased

monthly personal income was also statistically significant related to patient

awareness of diagnosis (p= 0.001). The

median duration of the disease of patients, who were aware of cancer diagnosis

was statistically significantly higher than those who stated that they did not

know their diagnosis was cancer (12 months versus 5, p=0.001). Patients with

continuation/change of treatment were more likely to know they had cancer than

those in the first cycle of treatment

(p<0.001). Patients with no co-existing disease were significantly more

likely to know they have cancer than those with a co-existing disease (p=0.03).

In addition, all outpatients knew their diagnosis, while 14.4% of inpatients

claimed they did know their diagnosis was cancer (p<0.001). Due to the

variety of cancer diagnosis and the number of patients, Table 2 shows the most

frequent cancer types of the study patients and the majority of the treatment

combination they underwent. Table2:Patients’ clinical characteristics Patients’

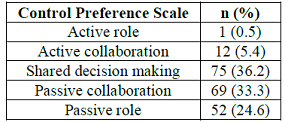

Decision-Making Preferences As

shown in Table 3, 36.2% (n=75) of

patients chose to play a shared-decision role with their doctor in the decision-making

process. 33.3% (n=69) preferred their doctor to make the final decision

regarding treatment after taking the patient’s opinion seriously (passive

collaboration role), while only 0.5% (n=1) of patients chose to make all

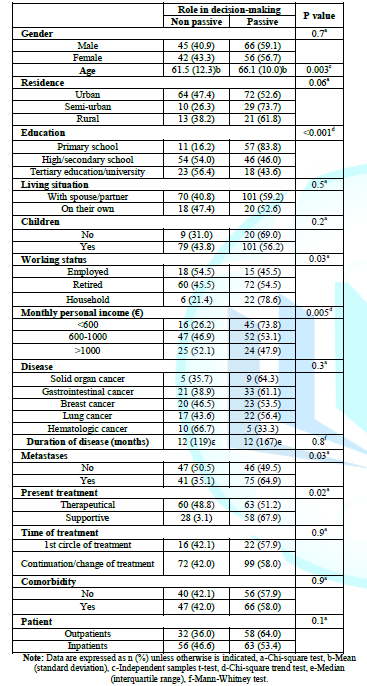

decisions regarding treatment on their own (active role). Bivariate analysis revealed the relationship

between demographic and clinical characteristics of the study patients and

their preferred role in the decision making process. Patients who chose the

passive and passive/collaborative role constituted one category (passive role)

(n=121), while patients who chose shared-decision, active/ collaborative and

active role constituted the second category (non-passive role) (n=88).

Dependent variable was the role patients prefer to play in the decision making

process. Table 4 shortly represents the most important results of the

analysis. Table 3: Patients’ decision-making preferences After the bivariate

analysis, there was a statistically significant relationship (p<0.20)

between the role patients prefer to play in the decision-making process and the

age, residence, education, the existence of children, the occupational status,

the monthly personal income, the existence of metastases, the type of treatment

and the type of patients (outpatients/inpatients). For this reason, multivariate

regression analysis was conducted, with a dependent variable the role

patients prefer to play in the decision-making process (non-passive role:

reference category), the results of which are presented in Table 5. The results of the multivariate regression analysis showed that older patients and those with lower educational level had an almost 1.04 and 2.63 times greater probability to adopt a passive role in decision-making procedures. The above variables interpret the 37% of the variability of passive role frequency volatility. Table 5:Multivariate regression analysis with the patient The vast majority of the study patients

knew their diagnosis was cancer (91.3%). Also, the largest percentage (57.9%)

of them preferred to play a passive role in the decision-making procedures

regarding cancer treatment. Both awareness of diagnosis and active/shared

decision-making role were significantly associated with younger age and higher

educational level. Out of 229, 209 (91.3%) knew they

suffered from cancer. Awareness of cancer diagnosis was found to be

considerably associated with age, residence, educational level, and monthly

personal income of the study patients. In particular, the elderly, patients who

live in semi-rural and rural areas, patients with only compulsory education and

those with an individual income of less than 600 euros per month were found to

be unaware of cancer diagnosis in a higher rate. In a study on Greek cancer

patients regarding awareness of cancer diagnosis conducted the previous decade

found that 59% of cancer patients stated that they did not know their diagnosis

[25]. Awareness

of diagnosis was also significantly related to younger age and higher

educational level, but also to female gender. In another study on Greek

population in 2002, the percentage of patients who were unaware of cancer

diagnosis was 63%. In this study, cancer patients who were mainly aware of

their diagnosis were younger, high/secondary school or university graduates and

suffering from breast cancer [6]. The Greek culture widely supports the

ignorance of diagnosis in cancer patient, while the greater supporters of this

phenomenon are the members of patients’ families. In Greece, family ties are

particularly strong and family members share an intense feeling of offer and

solidarity. Patients rely heavily on their family when they have serious

problems and, above all, health problems, but relatives themselves usually

experience patient health issues as a family issue and are actively involved in

the process of dealing with the disease [31]. In the context of this protection, the

fact that the diagnosis of cancer causes anxiety and sadness to patients,

especially the elderly, who may feel helpless to cope with the disease’s

challenges, relatives try to protect them by intervening and concealing not

only the real diagnosis but even the type of the given treatment. This tactic, although

still used nowadays, has gradually been replaced by the necessity of revealing

the truth to cancer patients. A recent study in Turkey, where family ties are

equally strong, shows that diagnosis has been hidden in cancer patients at high

rates. The reasons why patients' relatives

conceal the diagnosis of cancer are to a great extent the anxiety and

depression it may cause to sufferers. Specifically, in 129 newly diagnosed

cancer patients, 29.5% had no knowledge of the diagnosis, while relatives claimed

that revealing the truth would cause them severe psychological problems [32]. The same year in a study in India, where

socio-cultural conditions and perceptions also seem to impede disclosure of

diseases such as cancer, the vast majority of the cancer patients were unaware

of their diagnosis. Specifically, only 29.9% of patients, most of them with

non-small cell lung cancer and advanced disease knew they had cancer [33]. The previous decade in a study carried

out in Norway, it was found that awareness of diagnosis of cancer patients was

not certain. Specifically, 20% of study patients claimed that they did not know

they had cancer. These patients were predominantly male, very young or elderly

and smokers [34]. In a recent study in Philadelphia, it was found that the

increased education level of cancer patients was significantly associated with

increased level of awareness of cancer staging [35]. The study concluded that

health professionals must recognize patients who require special attention due

to their age or education level and evaluate whether they understood what their

doctors explained to them regarding their disease and treatment. On the other hand, revealing cancer

diagnosis is an unpleasant process for healthcare professionals as well. Given

the assumption that the disclosure of bad news may cause anxiety

and sadness to patients their families, they choose to hide the diagnosis of

cancer and ask the medical and nursing staff to do the same in an attempt to

protect them [36,37]. Breaking bad news to cancer patients is causing a great

anxiety to healthcare professionals, as they often do not know how to

communicate the news with the patient, without causing sadness and unpleasant

reactions. In addition, as it has been reported in previous studies, healthcare

professionals have difficulty in using the appropriate language and

understandable terms to simply and effectively explain to patients the details

of their disease and treatment [38,39]. The disclosure of this truth has been a

difficult process even for the most experienced doctors and nurses [40].

However, Greek healthcare professionals tend to increasingly adopt

international models of disclosure to cancer patients, although this process

remains particularly inconvenient and stressful for them [41,42]. It is, therefore, concluded that

awareness of diagnosis of cancer patients depend on different factors, which

are associated with health care professional as well as cancer patients and

their families. As far as the patient's preferences in

decision making procedure are concerned, the results of the statistical

analysis showed that 36.2% of cancer patients want to co-decide with their

doctor on their treatment, choosing the shared decision-making role. Only 5.8%

of the patients preferred a more active role, while 57.9% preferred a more

passive role, with 24.6% of them preferring a fully passive role, where the

doctor takes all responsibility for the treatment decisions. Also, it was found

that older and lower-educated patients preferred, in a higher rate, a more

passive decision-making role. In line with the above, another study has been,

recently, conducted on breast cancer patients in Greece. The majority of

patients wished to have a passive role in the decision making process (71.1%),

with most patients (45.3%) wanting their doctor to take full responsibility for

cancer treatment decisions. The shared decision role was chosen by 24% of

patients [16]. In a study among cancer patients, in

Canada, the roles in the treatment decision making process patients preferred

were 26% active, 25% passive and 49% collaborative. Older patients, women and

Canadian patients than US patients were more likely to assume a passive role.

Moreover, in a study in Switzerland, the vast majority of cancer patients (79.1%)

agreed to the statement “one should stick to the physician advice even if one

is not fully convinced of his idea”. Older patients and less educated patients

were more likely to agree to this statement [29,43]. Arguably, older cancer patients have

grown up in an era characterized by the “doctor-centered” model, which may help

to explain their more passive role in the decision-making procedures. It was

then believed that a patient would seem as “good customer”, trusting whatever

the doctor suggested, without asking for more information or discuss treatment

options [12]. Also, older patients might have lost hope, be depressed or

overwhelmed by cancer-related symptoms and thus be unwilling to participate in

the decision-making process [4]. On the other hand, patients with higher

education level might have the ability to better access and understand medical

information, which may affect patients’ preferred role in the decision-making

procedure with the health care team. Knowledge is power and it is certainly

easier for a patient with a good educational background to understand the

doctor’s words, ask questions and make choices [44]. The rate at which Greek cancer patients

choose a passive role in the decision making process is the highest compared to

the corresponding percentage in both past and recent studies, internationally [45-56].

In a recent study in Spain, 21.2% of cancer patients receiving palliative care

for their disease preferred a passive role in treatment decision process; while

in the USA the percentage was still comparatively lower (13%) [57,58]. Many factors are likely related with the

choice of passive role from Greek cancer patients. The paternalistic model of

treatment decision-making, which is still largely prevalent in Greece, affects

the counseling process with the health care team. Patients, usually, play a

passive role in consultation and may have learned from past experiences that a

more active role will not be easily accepted by healthcare professionals. Also,

patients are likely to think that by choosing a more active role, they may seem

recalcitrant patients and therefore not receive the proper care. Finally, apart

from the paternalistic model in the doctor-patient relationship and the fear of

the quality of care provided, the choices of Greek patients are likely to be

influenced by their families, whose role is more intrusive in our country,

resulting many times, as already mentioned, in concealing information from

patients regarding diagnosis and the developments in their health status [16,41]. An additional factor that is not often

mentioned but can greatly influence the degree to which patients will be

involved in the decision making procedure is the enormous lack of time on

behalf of healthcare professionals in order to allow time to further promote

discussion and communication with the patients and their family members. In the

recent years, hospitals in Greece are clearly under-staffed suffering serious

shortages in both materials and building infrastructure, which causes serious

problems in coordination, organization of time, and communication ultimately

causing a reduction of the quality of holistic care provided to patients

[41,59]. Active involvement of cancer patients in

decision-making procedures regarding treatment requires a safe and calm

environment, as well as healthcare professionals with high communication

skills. The patients and their families should have adequate time to discuss

with the healthcare team, share their concerns and express their wishes in

order to make the appropriate decisions, with which they would feel

comfortable, confident and satisfied. In addition, healthcare professionals

should promote patients expression of possible changes in their decisions, as

well as, the wish for further or detailed information regarding disease and

treatment [60]. Therefore, the combination of

inappropriate communication environment and the occupational exhaustion of

doctors and nurses in Greek hospitals make it difficult for patients to

participate in therapeutic decision-making in a more active way [41]. This study concerns a rather underrated

issue in Greece and a difficult issue to discuss with Greek patients. In Greek

reality, almost the last two decades, the enormous lack of healthcare

professionals, nursing staff and doctors along with the remaining hesitation of

patients in getting the information they need for cancer diagnosis, derive them

from their right to actively participate in decision-making procedures [16,18,27].

That is the reason why there are very few studies on the matter in Greece

throughout the years. On the other hand, in Netherlands, researchers conducted

a study about the preferences of cancer patients between two main treatments

for early glottic

cancer, which indicates that patients, in other countries in Europe, not

only participate in decision making processes, nowadays, but also choose

between treatments, when given a choice [61]. Therefore, the conduction of this

study managed to provide health care professionals with the actual preferences

of Greek cancer patients regarding their participation in decision-making and

to emphases the need for better communication between health care professionals

and cancer patients. This study had some limitations. The

study sample consisted of patients suffering from various cancer types and the

disease duration ranged from recent to many years. This may have confused

patients about the therapeutic decisions they had taken, perhaps, several years

ago and which could have changed over time. In addition the study sample was

relatively small, which might affect the external validity of the study. Also,

the study sample gathered from a single general hospital in Athens, which not

only limited its number, but it might affected the results, since patients from

purely cancer hospitals might be more aware of diagnosis and more active in the

decision-making procedures. Perhaps, a multicenter study would have yielded

more representative results and allow for additional correlations. The results of the study showed that

Greek patients are more aware about cancer diagnosis, nowadays, but wish to

have a mainly passive and, to a lesser extent, a shared-decision role in the

decision-making procedures. This fact shows that the prevalent paternalistic

model of doctor-patient relationship in Greek reality may overshadow the

patients' actual needs and hinter the expression of their wishes or objections

to decisions regarding treatment. This study, also, supports the need for a

unique and personalized patient care, at a time that in the country where the

study conducted, thousands of desperate people from different cultures are

flocking every day and the migration issue is a front line issue. Therefore,

even if the study results seem to address to Greek cancer patients, the truth

is that they apply to any cancer patient, who needs honest and person-centered medical

and nursing care and they could be included to cultural and migration patterns

round the world. Thus, health professionals should approach each patient and

his/her needs uniquely, by providing the appropriate information and options

available for cancer treatment, while being continuously alerted for signs of

intense anxiety and patient dissatisfaction. Despoina G Alamanou, 2nd Internal Medicine Department, 417 NIMTS Hospital of Athens, Greece,Tel: +00306937509784, E-mail: despina_alamanou@hotmail.com Alamanou DG, Giakoumidakis K, Theodosiadis DG, Fotos NV, Patiraki E, et al. Awareness of diagnosis and decision-making preferences of greek cancer patients (2020) Pharmacovigil and Pharmacoepi 3: 5-12. Cancer,

Decision-making, Diagnosis, Oncology, Patients' participation, Patients'

preferences, Role preference.Awareness of Diagnosis and Decision-Making Preferences of Greek Cancer Patients

Abstract

Full-Text

Methods

Results

Discussion

Strengths

Limitations

Conclusions

References

*Corresponding author

Citation

Keywords