Research Article :

Mohammed Ahmed Bamashmos and Khaled Al-Aghbari Hyperuricemia is a metabolic problem that has

become increasingly common worldwide over the past several decades. Its

prevalence is increased in both advanced and developing countries including

Yemen. The aim of this cross sectional study was to investigate the prevalence

of hyperuricemia in sample of Yemeni adult individual and its relationship to

certain cardiovascular risk factors namely obesity, hypertension, serum

glucose, total cholesterol, high serum triglyceride, Low High Density

Lipoprotein (HDL-C) and high Low Density Lipoprotein (LDL-C). A sample of 600 adult

Yemeni people aged equal or over 18 years was randomly chosen to represent the

population living in Sanaa City during a period of two years from April 2017 to

August 2018. All the study groups undergo full clinical history and examination

includes measurement of BP and BMI, WC and the following laboratory

investigation (FBS, Basal serum uric acid level, total cholesterol, serum TG,

HDL and LDL). The prevalence of

hyperuricemia in this study was 8.8% (11,6% male and 6.4% female). The serum

uric acid level in this study was significantly correlated with age, Waist

Circumference (WC), SBP, DBP, FBS, T-cholesterol, TG and LDL but not with HDL. There is strong

relationship between serum uric acid level and other cardiovascular risk

factors. Hyperurecemia

is metabolic problem that has become increasingly worldwide over the past

several decades and its the most risk factor for gout [1]. Hyperurecimea is

defining as serum urate level greater than 6mg/dl in in women and 7mg/dl in

men, above this concentration serum urate supersaturates in body fluid and is

prone to crystallization and subsequent deposition in the tissue [2].The

association of hyperurecemia and gout with other medical condition such as

hypertension, chronic kidney diseases, dyslipidemia and other cardiovascular

diseases has been recognized for over 100 years [3]. The prevalence of

hyperurecemia has been increased in recent years, not only in advanced

countries but also in developing countries along with the development with

their economics [4]. Published population-based prevalence data of

hyperuricemia were reported in 13 of the 21 Global Burden of Diseases

(GBD) regions, and a total of 24 countries. In most part of Asia Hyperuricemia

is relatively prevalent, but in East Asia it found to be most prevalent. Lowest

percentage is seen in Papua New Guinea 1% and in Marshall Islands 85% is seen. In japan the high income Asian country Hyperuricemia has

increased by five folds in time of two decades. There is no published

population-based epidemiological studies on hyperuricemia were identified

during the specified systematic review period [5]. Hyperuricemia can be causes

by over production of urate which account of less than 10% of the cause such as

high cellular turnover, genetic error and tumor lysis syndrome or far more

commonly inefficient excretion by the kidney due to renal insufficiency of any

cause or medication that impair renal urate clearance [6]. In numerous

epidemiological studies since 1950 a positive association has been seen between

serum uric acid and cardiovascular

diseases such as ischemic heart disease and stroke [7,8]. However weather uric acid is independent risk factor for

cardiovascular disease is still disputed as several studies has suggested that

hyperurecemia is merely associated with cardiovascular disease because of

confounding factors such as obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, use of

diuretic and insulin resistance [9]. Obesity and central fat distribution were

associated with hyperurecemia. Patients with central obesity have greater risk

of hyperurecemia [4]. There are many researches was conducted to evaluate the

relationship between leptin hormone and the cluster of hyperurecemia in order

to identify the pathogenic mechanism associating obesity with hyperurecemia. It

was suggested that leptin could be a pathogenic factor responsible for

hyperurecemia in obese patients [10]. The strong association between hypertension and

hyperurecemia has been recognized for more than century. More than one large

epidemiological studies published over the past 7 years have found that serum

urate level predict later development of hypertension [11,12]. Experimental studies have reported that hyperurecemia induces

systemic hypertension and renal injury via activation of renin angiotensin

system and direct intery of uric acid into both endothelial and vascular smooth

muscle cells, decreased neuronal nitric oxide synthase in the juxtaglomerular

apparatus resulting in local inhibition of endothelial nitric oxide level,

stimulation of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and stimulation of

vasoactive and inflammatory mediators [13,14]. There is strong association

between hypertriglycemia and hyperurecemia this association could be explained

by insulin resistance as hypertriglyceridemia and hyperurecemia are suggested to

be associated with insulin

resistance syndrome [15]. The association of hypertriglyceridemia and hyperurecemia in

patients with insulin resistance syndrome could be explained by accumulation of

glycolytic intermediate and release of free fatty acid from adipose tissue

[16]. The resemblance of hyperurecemia and the metabolic syndrome has led to

the suggestion that the metabolic syndrome can be further expanded to include

hyperurecemia [17]. A prospective study in Korea suggested that higher uric

acid concentration predicted the incidence of hypertension and the development

of metabolic syndrome and hyperurecemia has been considered as component of

metabolic syndrome [18,19]. This was across sectional population based study conducted in

Sanaa city for a period of 2 years between September 2016 and September 2018 a

sample of 600 adult Yemeni people (275 male and 325 female aged ≥ 18 years) was

randomly selected from those attending Al-Kuwait University Hospital and

Consultation Clinic. All the participants in this study undergo complete clinical

history (regarding their age, occupation, habit, any history of hypertension,

diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia and medication) Anthropometric measurement

includes measurement of height, weight, waist circumference and systolic and diastolic

blood pressure. Height was measured with tapeline to the nearest.5cm and

weight was measured with beam scale balance. Participants wore light clothing

and were asked to remove shoes, heavy outer garments Body Mass Index (BMI:

kg/m2) was calculated from measured weight and height. BMI was classified as

underweight (<18.5 kg/m2), normal (18.5-25 kg/m2), overweight (25-30 kg/m2)

and obese (>30 kg/m2) by WHO criteria [20]. Waist circumference was manually

measured on standing subjects with soft tape midway between the lowest rib and

the iliac crest. Abdominal obesity was defined as WC ≥ 90 cm (male) or WC ≥ 80

cm (female) by IDF consensus [21]. Two blood pressure recording were obtained from the right arm

of patients with slandered mercury sphygmomanometer

in a sitting position after 10 min. of rest measurement were taken in 3-5

minutes interval and the mean values were calculated. Blood pressure was

classified as normotensive (SBP<120 mmHg and DBP<80 mmHg),

pre-hypertensive (SBP: 120-139 mmHg and/or DBP: 80-89 mmHg) and hypertensive

(SBP ≥ 140 mmHg and/or DBP ≥ 90 mmHg) by the Seventh Report of the Joint

National Committee on the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of

High Blood Pressure (JNC-7) [22]. The American Diabetes Association criteria

was used to classify FBG as normal glucose (FBG<5.6 mmol/L), Impaired

Fasting Glucose (IFG) (FBG ≥ 5.6 mmol/L ≤ FBG<7.0 mmol/L), and diabetic (FBG

≥ 7.0 mmol/L, Serum uric acid were measured [23]. Hyperurecemia is defined as

serum uric acid level greater than 6.0mg/|dl in women and 7.0 mg/dl in men.

Dyslipidemia was classified according to ATP III, TG: Normal<1.69 mmol/L,

Borderline high 1.69-2.26 mmol/L, High 2.26-5.65 mmol/L, Very high ≥ 5.65

mmol/L; TC: Desirable<5.17 mmol/L, Borderline high 5.17-6.24 mmol/L, High ≥

6.24 mmol/L; HDL-C: High 1.56 mmol/L, Optimal 1.03-1.56 mmol/L, Low The results were analyzed by using (Social Package of

Statistical Science) SPSS V.15 from LEAD Technologies Inc., USA. Basic

characteristics of subjects are presented as mean and slandered deviation for

quantities variables and as frequency and percent for qualitative variable. The

total participants were divided into two groups according to the sex then there

were divided into two mean groups according to serum uric acid level. The

prevalence of cardiovascular diseases risk factors among two groups were

calculated and Chi-square

test was used to detect the significance /The mean of uric acid in

different categories of separated variable were determined and the comparison

between the mean was achieved by independent t-test and one way ANOVA test. The

relationships between parameters were examined by calculating persons

correlation coefficient. For investigating for most effective factors on

hyperurecemia such as blood pressure anthropometrical and biochemical (except

UC) measurement were considered for Binary logistic regression P-value less

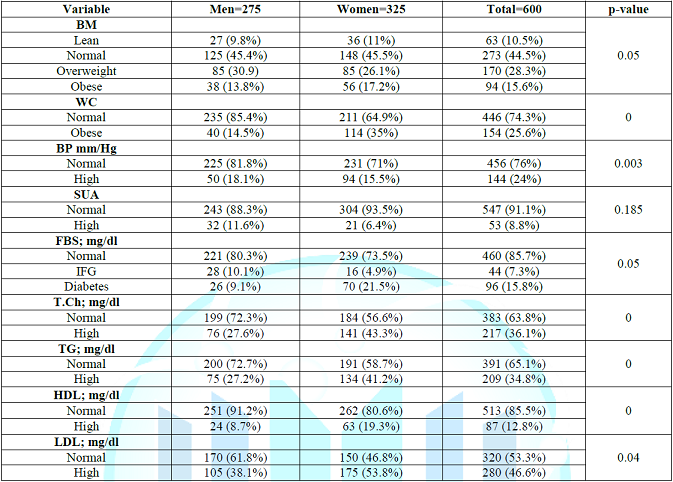

than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. A study sample includes 600 person aged between 18-83 of them

275 (45.4%) were male and 325 (54.6%) were female. The prevalence of high serum

uric acid level in the study group was 53 (8.8%) with no significant difference

between male and female (Table 1) regarding the clinical and laboratory

parameters in the study group BMI. WS, serum cholesterol, high TG, low high

density lipoprotein, high LDL and high FBS were significantly higher in women

than in men (17.2%, 35%, 43.3%, 41.2%, 19.3%, 53.8% and 26.4% vs 13.8%, 14.5%,

27.6%. 27.2%, 8.7%, 38.1% and 19.2% respectively, while the BP was

significantly higher in men than women, also there was no significant

difference between male and female regarding serum uric acid level. Hyperurecemia is increasingly common medical problem not only

in the advanced countries, but also in the developing countries. The incidence

of high serum uric acid is increased word wide with average of 20% of

population having hyperurecemia and the serum uric acid level is increased with

age. It has been described that hyperurecemia is associated with other

cardiovascular risk factors such as obesity, dyslipidemia,

hyperglycemia and hypertension [1-3]. Elevated serum uric acid levels are

commonly seen in association with glucose intolerance, hypertension and

dyslipidemia, a cluster of metabolic and hemodynamic disorders

which characterize the so-called metabolic syndrome [25-29]. To our knowledge

there is no data about the prevalence of hyperurecemia in Yemen so we decided

to carry out this research in order to know the prevalence of hyperurecemia and

its association with other cardiovascular risk factors in Yemeni population. Note: SUA-Serum

Uric Acid, FBS- Fasting Blood Sugar, IFG- Impaired Fasting Glucose, T.Ch- Total

Cholesterol, TG- Triglyceride, HDL- High Density Lipoprotein, LDL- Low Density

Lipoprotein. Table 1: Shows the clinical and laboratory characteristics of

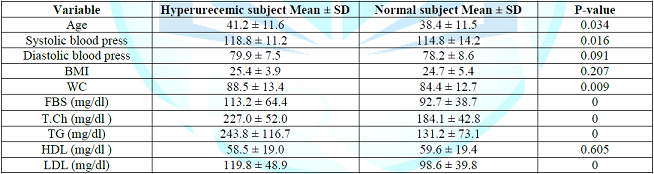

the study group. Note: Table 2

present comparing the mean of selected study parameters in relation to the uric

acid level, it shows the mean of age, SBP, WS, fasting blood glucose, total

cholesterol, TG and LDL were significantly higher within hyperurecemic study

population in comparing to those with normal serum uric acid level, there were

no significant difference in DBP, BMI and HDL between the two groups. Note: Table 3

shows the simple correlation coefficients between serum uric acid levels and

the various cardiovascular risk factors in the population. Uric acid was

significantly positively correlated with age, SBP, FBS, TG, total cholesterol,

LDL (P-value ≤ 0.01) and weak positive correlated with DBP, BMI and WC (P-value

≤ 0.05 ) while it was insignificantly correlated with HDL (P-value 0.411). The mean observations of the present study are the following;

firstly the prevalence of hyperurecemia present in a good proportion in Yemeni

peoples and it was insignificantly high in women than in men. Secondly

significant correlation between serum uric acid the various cardiovascular risk

factors were found. The prevalence of hyperurecemia in the present study was

8.8%, which is mainly near to that reported in Saudi Arabia (9.3%), Iran (8%),

Thailand (9-11%), Mexico (11%) and in Turkish (12%) which may be reflected to

similar race and environmental factors. while its lower than that found in

Columbia (26.3%). Indian (25.8%), Taiwan (30.4%) and USA (21-22%) which may be

attributed to the high economic state of this countries. Hyperurecemia was

insignificantly higher in women (7.9%) than men (6.3%) which may be explained

by high prevalence of obesity in women (BMI and WC was 17.2%, 35% in women VS

13.8% and 14.1% in in men respectively. This finding was supported by study

done in Saudi Arabia and but other studies are against this observation.

Comparing hyperurecemic subject with those with normal serum uric acid level,

those with hyperurecemia are older centrally obese, had high systolic blood

pressure, high FBS, total cholesterol, triglyceride, and LDL

[30-36] (Table 2). In this study, multiple logistic regression results have

further confirmed the association between metabolic abnormalities and high

serum uric acid, and have conducted further stratified analysis on each

metabolic abnormality-related indicator. Table 3 shows the simple correlation

coefficients between serum

uric acid levels and the various cardiovascular risk factors in the

population. Our results have shown that high serum uric acid was significantly

positively correlated with age, SBP, FBS,TG, total cholesterol, LDL (P-value ≤

0.01) and weak positive correlated with DBP, BMI and WC (P-value ≤ 0.05 ) while

it was insignificantly correlated with HDL (P-value 0.411) [35]. Elevation of the serum uric acid level has been known

associated with major cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension,

insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and obesity, which are hallmarks of metabolic

syndrome [36-39]. Similar to other studies, in this study, individuals with

hyperuricemia had higher prevalence of major cardiovascular risk factors,

including dyslipidemia, hypertension and overweight. Uric Acid (UA) is a known

endogenous scavenger, which provides a major part of the antioxidant capacity

against oxidative and radical injury. However, at high levels, UA can shift

from an antioxidant to a pro-oxidant factor (shuttle capacity),

depending on the characteristic of the surrounding microenvironment (e.g., UA

levels, acidity, depletion of other antioxidants, reduced Nitric Oxide (NO),

availability) [40,41]. Accordingly, high UA values have been associated with

metabolic syndrome, Cardiovascular Disease (CVD), and renal dysfunction,

involving mechanisms that favor oxidative stress, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction.

The result of this study showed significant positive correlation were found

between serum uric acid and several component of the metabolic syndrome such as

higher WS, BP, TG and FBS (p-value ≤ 0.005) but there was insignificant

negative correlation with HDL. Several possible pathophysiological mechanisms

have been evoked to explain these associations including insulin resistance,

the use of diuretics or impaired renal function accompanying hypertension

[42-49]. Indeed the kidney seems to play an important role in the

development of the metabolic syndrome. Insulin-resistant individuals secrete

larger amounts of insulin in order to maintain an adequate glucose metabolism.

The kidney which is not insulin-resistant responds to these high insulin levels

by decreasing uric acid clearance, probably linked to insulin-induced urinary

sodium retention. Insulin resistance may increase blood pressure directly via

enhanced proximal tubular sodium reabsorption or indirectly by the sympatho-adrenal system

[43-45]. Thereby, the kidney has been implicated as the potential link between

muscle insulin resistance and compensatory hyperinsulinemia and the development

of hyperuricemia and eventually hypertension. Our study demonstrates an alarming high prevalence of

hyperurecemia among Yemeni patients that increases the burden on overstrained

Yemeni health system with uprising CVDs and other hyperurecemia related health

problems e.g. hypertension, dyslipidemia DM. There is also an urgent need to

develop strategies for prevention, detection, and treatment of hyperurecemia

that could contribute to decreasing the incidence of grave consequences such

cardiovascular disease and chronic renal diseases. 1.

Terkeltaub RA. Clinical practice Gout (2003) N Engl

Med 349. 2.

Sachs L, Batra LK and Zimmermann B. Medical implication

of hyperurecemia (2009) Med Healt Rhode Island 92: 353. 3.

Feig DIU, Kang DH and Johnson RJ. Uric acid and

cardiovascular risk (2008) N Engl Med 359: 1811-1821. 4.

Li-ying C, Wen H, Chen Z, Dai H and Ren J.

Relationship between hyperurecemia and metabolic syndrome (2007) J Zhejiang

University Sci 8: 593-598. 5.

Smith E and March L. Global Prevalence of

Hyperuricemia: A Systematic Review of Population-Based Epidemiological Studies

(2015) Am collage rheumatol 9. 6.

Andrew J, Luk M and Simkin P. Epidemiology of

hyperirecemia and gout (2005) Am collage managed care 11: s435-s442. 7.

Gertler MM, Gam SM and Levine SA. Serum uric acid

level in relation to age and physique in health and coronary heart diseases

(1951) Ann Intern Med 34: 1421-1431. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-34-6-1421

8.

Fang J and Alderman MH. Serum uric acid level and

cardiovascular mortality; The NHANES 1 epidemiology follow up study 1971-1992

(2000) JAMA 283: 2404-2410. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.283.18.2404

9.

BurnierM and BrunnerHR. Is hyperurecemia a predictor

of cardiovascular risk? (1999) Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 8: 167-172. 10.

Fruehwald SB and PetersA, Kern W and Beyer J. Serum

leptin is associated with serum uric acid concentrations in humans (1999)

Metabolism 48: 677-680. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0026-0495(99)90163-4

11.

Perlstein TS, Gumieniak O and Williams GH. Uric acid

and the development of hypertension in normotensive aging study (2006)

Hypertension 48: 1013-1036. 12.

Krishnan E, Kwoh CK, Schumacher HR and Kuller L.

Hyperurecemia and incidence of hypertension among men without metabolic syndrome

(2007) Hypertension 49: 298-303. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.hyp.0000254480.64564.b6

13.

Mazzali M, Kanellis J, Han L, Feng L, et al.

Hyperurecemia induce primary arteeriopathy in rats by a blood pressure

independent mechanism (2002) Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 282: F991-F997. 14.

Johnson RJ. Kang DH and Feig D. Is there apathogenetic

rule for uric acid in hypertension and cardiovascular and renal diseases (2003)

Hypertension. 15.

Bosello E and Zamboni M. Visceral obesity and

metabolic syndrome (2000) Obes Rev 1: 47-56. 16.

Leyva F, Wingrove CS and Godsland IF. The glycolytic

pathway to coronary herat diseases; ahypothesis (1998) Metabolism 47: 6657-662. 17.

Klein BEK, Klein R and Lee KE. Components of metabolic

syndrome and risk of cardiovascular diseases and diabetes in Beaver Mam (2002)

Diabetes Care 25: 1790-1794. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.25.10.1790

18.

Yoo TW, Sung KC, Shin HS, Kim BS, Lee HM, et al.

Relationship between serum uric acid concentration and insulin resistance and

metabolic syndrome (2005) Circ J 9: 928-933. https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.69.928

19.

Onat A, Uyarel H, Hergenc G, Karabulut A, Albayrak S,

et al. Serum uric acid is a determinant of metabolic syndrome in

population-based study (2006) Am J Hypertens 19: 1055-1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjhyper.2006.02.014

20.

Allison DB, Downey M, Atkinson RL, et al. Obesity as a

disease: a white paper on evidence and arguments commissioned by the Council of

the Obesity Society (2008) Obesity (Silver Spring) 16: 1161-1177. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2008.231

21.

Hou X, Lu J, Weng J, Ji L, Shan Z, Liu J, Billington

JC, Bray AG, et al. Impact of waist circumference and body mass index on risk

of cardio metabolic disorder and cardiovascular disease in Chinese adults: a

national diabetes and metabolic disorders survey (2013) PLoS One 8: e57319. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0057319

22.

European Society of Hypertension-European Society of

Cardiology Guidelines Committee: Guidelines for the management of arterial

hypertension (2003) J Hypertens 21: 1011-1053. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004872-200306000-00001

23.

American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical

Care in Diabetes-2011 (2011) Diabetes Care 34: S11-S61. https://dx.doi.org/10.2337%2Fdc11-S011

24.

Expert panel on detection, evaluation and treatment of

high blood cholesterol in adults. Executive summary of the third report of the National

Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) (Adult Treatment Panel III) (2001) JAMA

285: 2486-2497. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.285.19.2486

25.

Bonora E, Targher G, Zenere MB, Saggiani F, Cacciatori

V, et al. Relationship of uric acid concentration to cardiovascular risk

factors in young men. Role of obesity and central fat distribution. The verona

young men atherosclerosis risk factors study (1996) Int J Obes Relat Metab

Disord 20: 975-980. 26.

Zavaroni I, Mazza S, Fantuzzi M, DallAglio E, Bonora

E, et al. Changes in insulin and lipid metabolism in males with asymptomatic

hyperuricemia (1993) J Intern Med 234: 25-30. 27.

Vuorinen-Markkola H and Yki-Järvinen H. Hyperuricemia

and insulin resistance (1994) J Clin Endocrinol Metab 78: 25-29. https://doi.org/10.1210/jcem.78.1.8288709

28.

Facchini F, Ida Chen Y-D, Hollenbeck CB and Reaven GM.

Relationship between resistance to insulin-mediated glucose uptake, urinary

uric acid clearance and plasma uric acid concentration (1991) JAMA 266:

3008-3011. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.1991.03470210076036

29.

Reaven GM. The kidney: an unwilling accomplice in

syndrome X (1997) Am J Kidney Dis 30: 928-931. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-6386(97)90106-2

30.

Al-arfa AS. Hyperurecemia in Saudia Arabia (2001)

Rhaumatol Int 20: 61-64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002960000076

31.

Smith E and March L. Global Prevalence of

Hyperuricemia: A Systematic Review of Population-Based Epidemiological Studies

(2015) Arthritis Rheumatol 67. 32.

Sari I, Akar S, Pakoz B and Sisman AR. The prevalence

of hyperurecemia in an urban population, Izmer Turkey (2009) Rheumatol Int 29:

869-874. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00296-008-0806-2

33.

Lombo B, Melo AA, Benavides J and Lopez M. Prevalence

of Hyperuricemia and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in a Population from Colombia

(2010) World congress of cardiology, China, 122. 34.

Billa G, Dargad R and Mehta A. The prevalence of hyperurecemia

in indian subject attending hyperurecemia screening program -A retrospective

study (2018) J the association of phys ind 66. 35.

Qian Yu, Hsi-che Shen, Yi-chun Hu, Yu-fen Chen and

Tao-hsin Tung. Prevalence and Metabolic Factors of Hyperuricemia in an Elderly

Agricultural and Fishing Population in Taiwan (2017) Arch Rheumatol 32:

149-157. https://doi.org/10.5606/archrheumatol.2017.6075

36.

Masuo K, Kawaguchi H, Mikami H, Ogihara T and Tuck ML.

Serum uric acid and plasma norepinephrine concentrations predict subsequent

weight gain and blood pressure elevation (2003) Hypertension 42: 474-480. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.hyp.0000091371.53502.d3

37.

Sundström J, Sullivan L, DAgostino RB, Levy D, William

B, et.al. Relations of serum uric acid to longitudinal blood pressure tracking

and hypertension incidence (2005) Hypertension 45: 28-33. 38.

Li C, Hsieh MC and Chang SJ. Metabolic syndrome,

diabetes, and hyperuricemia (2013) Current opinion in rheumatology 25:210-216. https://doi.org/10.1097/bor.0b013e32835d951e

39.

Puig JG and Martinez MA. Hyperuricemia, gout and the

metabolic syndrome (2008) Current opinion in rheumatology 20:187-191. https://doi.org/10.1097/bor.0b013e3282f4b1ed

40.

Ames BN, Cathcart R, Schwiers E and Hochstein P. Uric

acid provides an antioxidant defense in humans against oxidant- and

radical-caused aging and cancer: A hypothesis (1981) Proc Natl Acad Sci 78:

6858-6862. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.78.11.6858

41.

Pingitore A, Lima GP, Mastorci F, Quinones A, Iervasi

G, et.al. Exercise and oxidative stress: Potential effects of antioxidant

dietary strategies in sports (2015) Nutrition 31:916-922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2015.02.005

42.

Gliozzi M, Malara N, Muscoli S and Mollace V. The

treatmentof hyperuricemia (2015) Int J Cardiol. 43.

Battelli MG, Polito L and Bolognesi A. Xanthine

oxidoreductase in atherosclerosis pathogenesis: Not only oxidative stress

(2014) Atherosclerosis 237: 562-567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.10.006

44.

Billiet L, Doaty S and Katz DJ. Review of

hyperurecemia as marker of metabolic syndrome (2014) ISRN Rhaumatology Pp: 1-7.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/852954

45.

Reaven GM. The kidney: an unwilling accomplice in

syndrome X (1997) Am J Kidney Dis 30: 928-931. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90106-2

46.

Rathmann W, Funkhouser E, Dyer AR and Roseman JM.

Relations of hyperuricemia with the various components of the insulin

resistance syndrome in young black and white adults: the CARDIA study. Coronary

Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (1998) Annals Epidemiol 8: 250-261. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1047-2797(97)00204-4

47.

Agamah ES, Srinivasan SR, Webber LS and Berenson GS.

Serum uric acid and its relations to cardiovascular disease risk factors in

children and young adults from a biracial community: The Bogalusa Heart Study

(1991) J Lab Clin Med 118: 241-249. 48.

Lee J, Sparrow D, Vokonas PS, Landsberg L and Weiss

ST: Uric acid and coronary heart disease risk: evidence for a role of uric acid

in the obesity-insulin resistance syndrome. The Normative Aging Study (1995) Am

J Epidemiol 142: 288-294. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117634

49.

Bruno G, Cavallo-Perin P, Bargero G, Borra M, Calvi V,

et.al. Prevalence and risk factors for micro-and macroalbuminuria in an Italian

population-based cohort of NIDDM subjects (1996) Diabetes Care 19: 43-47. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.19.1.43 Mohammed Ahmed Bamashmos, Associate Professor of

internal medicine and Endocrinology, Sanaa University, Yemen, E-mail: mohbamashmoos@yahoo.com Bamashmos AM and

Al-Aghbari K. Prevalence of hyperuricemia and its association with other

cardiovascular risk factors in adult Yemeni people of Sanaa city (2019)

Clinical Cardiol Cardiovascular Med 3: 10-14. Hyperurecemia, Dyslipidemia, BMI, FBS.Prevalence of Hyperuricemia and its Association with Other Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Adult Yemeni People of Sana City

Abstract

Objective: Full-Text

Introduction

Material

and method

Results

Discussion

Conclusion

References

*Corresponding author:

Citation:

Keywords