Review Article :

Juan Simon Rico-Mesa, Stephanie Cornell and Rushit Kanakia Aspirin was once the mainstay of stroke prevention in

patients with atrial fibrillation. Its popularity was based on the results of

the SPAF and PATAF trials, which showed the low risks of this therapy and the

many benefits it had to offer in terms of embolic complications prevention.

Nevertheless, aspirin has lost popularity in atrial fibrillation since the

CHADS, CHA2DS2-VASc and HASBLED scoring systems were

first introduced. These scoring systems showed a different perspective, which

highlighted that thromboembolic risk varied among individuals and that a

generalization on antiplatelet therapy for atrial fibrillation was not

effective. These caveats gave support to additional treatments based on

anticoagulation, including warfarin and direct oral anticoagulants. These

treatments gained popularity based on the superiority over warfarin, first

described on the BAFTA trial, which nominated the warfarin as the standard of

care for atrial fibrillation thromboembolic prevention. Since then, direct

anticoagulation therapies have gained popularity based on the results of the

ARISTOTLE (apixaban), RE-LY (dabigatran), ROCKET-AF (rivaroxaban), ENGAGE TIMI

48 AF (edoxaban) trials. However, the CHA2DS2-VASc score

was generous with aspirin, since it opened a possible recommendation for low CHA2DS2-VASc

scores (0-1). This comprehensive literature review is intended to discuss the

arguments behind this last statement and to show the available evidence in

favor of and against aspirin for non-valvular atrial fibrillation in low

thromboembolic risk patients. Aspirin

was once the mainstay of stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. However, the

development of Vitamin K Antagonists (VKAs) and the evolution and availability

of Direct Oral

Anticoagulants (DOACs), has left aspirin (ASA) therapy by the wayside,

based on the results of the BAFTA, ARISTOTLE, RE-LY and ROCKET-AF trials. Both

ASA as monotherapy and ASA as dual-antiplatelet therapy are no longer

recommended as first line stroke prevention in patients with CHA2DS2-VASc

≥ 2 [1,2]. Exceptions in the guidelines exist only in certain clinical settings,

particularly in those with CHA2DS2-VASc score=1 [3].

Besides primary outcomes, including endpoints such as cardiovascular death and

mortality, VKAs have additionally shown no increased risk of bleeding compared

to ASA, especially among the moderate to high-risk sub-group of atrial

fibrillation patients [4,5,6-9]. Regarding ASA use for cardiovascular benefit, ASA is

ineffective at increasing disability-free survival or at decreasing mortality

among healthy elderly adults without clear risk factors [10,11]. This calls

into question the popular assumption that the benefits of ASA therapy for cardiovascular

health of the general population outweigh negative side effects. Therefore, ASA

use overall should be carefully assessed, particularly in patients with atrial

fibrillation. Interestingly, even more than a decade after the first

generation of studies showing superiority of VKAs for stroke prevention in

atrial fibrillation, ASA continues to be prescribed to patients with CHADS2

scores of greater than or equal to 2 despite overwhelming evidence against,

based on the results of the PINNACLE trial, which involved 210,380 patients

with high CHADS2 scores [12]. In fact, in 2012 the European Society

of Cardiology

recommended ASA for patients who refused anticoagulation, consistent with

evidence at the time that ASA did have benefit over no therapy for this patient

population [13]. Regarding specifically lower risk patients, the 2014 American

College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines recommend no

antithrombotic therapy or treatment with an oral anticoagulant or aspirin for

non-valvular atrial fibrillation with CHA2DS2-VASc=1 [2].

With a spotlight on ASA this year in the literature, it is appropriate to

re-evaluate ASA as alternative therapy to VKA or DOAC for patients with atrial fibrillation.

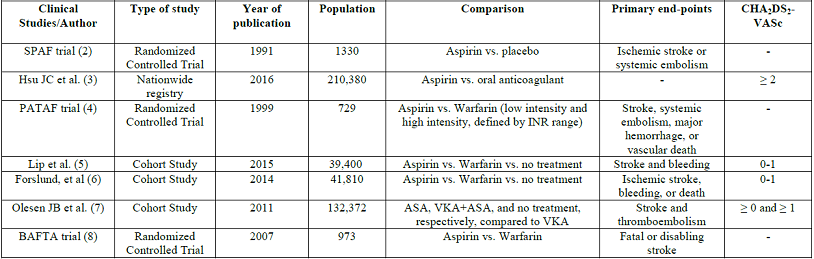

Specifically, evidence should be evaluated behind the benefit of ASA vs VKA or

DOAC vs no therapy for patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and CHA2DS2-VASc=0

or 1 (Table 1). The evidence for ASA for stroke prevention in patients with

atrial fibrillation with low risk of stroke (CHADSVASC<2) stems from the

Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation (SPAF) trial, published in 1991, which

followed patients for a mean of 1.3 years and found a 42% reduction in ischemic

stroke and embolism, as well as decreased mortality, with ASA compared to

placebo. Nevertheless, the SPAF trial also looked at warfarin outcomes and

found that warfarin had a superior reduction of primary events or death

compared to aspirin, 58% (p=0.01) vs. 32% (p=0.02). The risk of significant

bleeding was 1.5% vs. 1.4%, respectively [2]. Based on this early study, ASA

appeared to be a safe and effective (albeit less so) alternative to VKAs. Nevertheless, this study was performed in an era where

CHADSVASC had not been described before, and generalization among different

thrombotic risks and lack of standardized criteria was evident. Even though the

SPAF trial gave a hope for aspirin, evidence has been slowly proving it

differently. In 2000, the Primary Prevention of Arterial Thromboembolism in

Nonrheumatic Atrial Fibrillation (PATAF) trial supported the popular opinion

that ASA was an accessible and inexpensive therapy for those at low risk of stroke

or embolism, with a decreased risk of bleeding compared to anticoagulation and

a low drug-interaction

profile. It should be noted, however, that the PATAF trial was a relatively

small study of a uniform, elderly population in the Netherlands [14]. This study also found that ASA did not decrease risk of

bleeding compared to warfarin. Specifically, this study supported a neutral or

positive net clinical effect of warfarin over ASA in low risk patients with

atrial fibrillation, which contradicts the prior assumption that as risk

decreased, the efficacy of ASA increased enough to become clinically indicated

[16]. This study was the cornerstone for developing the most recent studies

that advocate for anticoagulation

over antiplatelet in CHA2DS2-VASc ≥ 1. Numerous other

studies throughout the last several decades also support either similar

bleeding risk or insignificant difference in bleeding risk between ASA and VKA

or between ASA and DOACs [4,5,6-8]. A Swedish study in 2014 also evaluated the risk of stroke or

embolism in atrial fibrillation. Their findings were consistent with a low

support of ASA in low risk patients, finding that patients with CHA2DS2-VASc

scores of 0-1 had a 1.0-1.2% one-year risk of ischemic stroke with ASA therapy

compared to a 0.1-0.2% risk without any treatment, which suggests that ASA

likely has no clinical benefit compared to no therapy for patients with low

risk of stroke or embolism [17]. It should be noted that both the

aforementioned Danish and this Swedish study were regional studies with

presumably homogenous populations, thus lacking external validity in other

populations and ethnicities. A recent study published in 2015 by Lip, et al. compared ASA

to warfarin therapy for primary prevention of stroke or embolism in those with CHA2DS2-VASc

scores of 0 or 1 [18]. They included a total of 39,400 patients, of which

10,475 were treated with VKAs; 5,353 were treated with ASA; and 23,572 were

left untreated. Primary endpoints, including stroke, bleeding and death, were

evaluated by both an intention-to-treat and Continuous Treatment analyses. The

authors found that for those with a low risk of stroke or embolism, defined as CHA2DS2-VASc=0

for males and CHA2DS2-VASc=1 for females, the risk of

stroke, bleeding, and death was truly low, and there was therefore no net

clinical benefit of treatment with either VKA or ASA. In those with one additional risk factor (CHA2DS2-VASc=1

for male and CHA2DS2-VASc=2 for female), ASA did not

significantly reduce risk of stroke and was significantly associated with

increased risk for

bleeding, i.e., regardless of sex, ASA therapy does not prevent stroke in

those with CHA2DS2-VASc=1, and furthermore does not

prevent stroke in women with CHA2DS2-VASc=2. However, in

untreated patients with one additional risk factor (CHA2DS2-VASc=1

for male and CHA2DS2-VASc=2 for female), 1-year stroke

risk increased by 3.01-fold, bleeding by 2.35-fold and death by 3.12-fold. The

authors also found that for those with one additional risk factor (CHA2DS2-VASc=1

for male and CHA2DS2-VASc=2 for female), there were

reductions in stroke and death with VKAs compared to no treatment and with VKAs

compared to ASA, without a significant increase in bleeding with VKA vs ASA

[18] . In the last three decades, ASA therapy has repeatedly been

found to be inferior to anticoagulation for preventing stroke in patients with

non-valvular atrial fibrillation, even for those with low risk of embolism or

stroke (CHA2DS2-VASc ≤ 1). Furthermore, ASA is not

associated with decreased risk of bleeding compared to VKA. The net benefit of

ASA therapy for these patients, therefore, does not have supporting evidence,

and we conclude that patients with low CHA2DS2-VASc

should not be offered ASA as a safer alternative to anticoagulation. Reasons to

prescribe ASA in this patient population include availability, financial

accessibility, and convenience, but these values are counterbalanced by similar

bleeding risk to VKA and significantly decreased efficacy at preventing the

primary outcome. 1. Ruff CT,

Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, Hoffman BE, Deenadayalu N, et al. Comparison of the

efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with

atrial fibrillation: A meta-analysis of randomised trials (2014) The Lancet

383: 955-962. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62343-0

2. January

CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, Calkins H, Cigarroa EJ, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline

for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: A report of the

american college of cardiology/american heart association task force on

practice guidelines and the heart rhythm society (2014) J Am Coll Cardiol 64:

e1-e76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.03.022

3. Valgimigli

M, Bueno H and Byrne RA. 2017 ESC focused update on dual antiplatelet therapy

in coronary artery disease developed in collaboration with EACTS (2017) Eur J

cardio-thoracic sur 53: 34-78. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx638

4. Stroke

prevention in atrial fibrillation study: Final results (1991) Circulation 84:

527-539. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.84.2.527

5. Mant J,

Hobbs FR, Fletcher K, Roalfe A, Fitzmaurice A, et al. Warfarin versus aspirin

for stroke prevention in an elderly community population with atrial

fibrillation (the birmingham atrial fibrillation treatment of the aged study,

BAFTA): A randomised controlled trial (2007) The Lancet 370: 493-503. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61233-1

6. Adjusted-dose

warfarin versus low-intensity, fixed-dose warfarin plus aspirin for high-risk

patients with atrial fibrillation: Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation III

randomised clinical trial (1996) The Lancet 348: 633-638. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03487-3

7. Albers

GW, Dalen JE, Laupacis A, Manning WJ, Petersen P, et al. Antithrombotic therapy

in atrial fibrillation (2001) Chest-Supplements 119: 194S-206S. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.119.1_suppl.194S

8. Hart RG,

Pearce LA and Aguilar MI. Meta-analysis: Antithrombotic therapy to prevent

stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (2007) Ann Intern

Med 146: 857-867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2015.07.003

9. Potpara

TS and Lip GY. Oral anticoagulant therapy in atrial fibrillation patients at

high stroke and bleeding risk (2015) Prog Cardiovasc Dis 58: 177-194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2015.07.003

10. McNeil JJ,

Woods RL, Nelson MR, Reid CM, Kirpach B, et al. Effect of aspirin on

disability-free survival in the healthy elderly (2018) N Engl J Med 379:

1499-1508. 11. McNeil JJ,

Nelson MR, Woods RL, Lockery JE, Wolfe R, et al. Effect of aspirin on all-cause

mortality in the healthy elderly (2018) N Engl J Med 379: 1519-1528. 12. Hsu JC,

Maddox TM, Kennedy K, Katz FD, Marzec NL, et al. Aspirin instead of oral

anticoagulant prescription in atrial fibrillation patients at risk for stroke

(2016) J Am Coll Cardiol 67: 2913-2923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.03.581

13. Camm AJ,

Lip GY, De Caterina R, Savelieva I, Atar D, et al. 2012 focused update of the

ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: An update of the 2010

ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed with the

special contribution of the european heart rhythm association (2012) Eur Heart

J 33: 2719-2747. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht291

14. Hellemons

BS, Langenberg M, Lodder J, Schouten HJA, Van Ree JW, et al. Primary prevention

of arterial thromboembolism in non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation in primary

care: Randomised controlled trial comparing two intensities of coumarin with

aspirin (1999) BMJ 319: 958-964. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.319.7215.958

15. Connolly

S, Pogue J, Hart R, Pfeffer M, Hohnloser S, et al. Clopidogrel plus aspirin

versus oral anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation in the atrial fibrillation

clopidogrel trial with irbesartan for prevention of vascular events (ACTIVE W):

A randomised controlled trial (2006) Lancet 367: 1903-1912. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68845-4

16. Olesen JB,

Lip GY, Lindhardsen J, Lane AD, Ahlehoff O, et al. Risks of thromboembolism and

bleeding with thromboprophylaxis in patients with atrial fibrillation: A net

clinical benefit analysis using a real world nationwide cohort study (2011)

Thromb Haemost 106: 739-749. https://doi.org/10.1160/TH11-05-0364

17. Forslund

T, Wettermark B, Wändell P, von Euler M, Hasselström J, et al. Risks for stroke

and bleeding with warfarin or aspirin treatment in patients with atrial

fibrillation at different CHA2DS2-VASc scores: Experience

from the stockholm region (2014) Eur J Clin Pharmacol 70: 1477-1485. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-014-1739-1

18. Lip GY,

Skjøth F, Rasmussen LH and Larsen TB. Oral anticoagulation, aspirin, or no

therapy in patients with nonvalvular AF with 0 or 1 stroke risk factor based on

the CHA2DS2-VASc score (2015) J Am Coll Cardiol 65:

1385-1394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.01.044

Juan Simon Rico-Mesa, Department of Medicine, Division of Internal Medicine,

University of Texas Health San Antonio, USA, E-mail: mesajs@uthscsa.edu Rico-Mesa SJ, Cornell S and Kanakia R. Current evidence for the use of

aspirin in patients with atrial fibrillation and a CHA2DS2-VASc=1

(2019) Clinical Cardiol Cardiovascular Med 3: 7-9. Atrial fibrillation, Anticoagulation therapies,

Cardiovascular health.Current Evidence for the Use of Aspirin in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation and a CHA2DS2-Vasc=1

Abstract

Full-Text

Background

The

Evidence

More recently, a meta-analysis published in 2007 supported these early

findings. Hart et al. concluded that ASA did reduce risk of stroke and embolism in

patients with atrial fibrillation by 20% compared to placebo, in addition to a

similar decrease in mortality. Nonetheless, warfarin was found to reduce stroke

by 60%. Of note, this meta-analysis included patients with both low and high CHA2DS2-VASc

values. Sub-group analysis was not performed, so conclusions for low vs high CHA2DS2-VASc

values were not assessed. Most studies included in this meta-analysis

specifically targeted primary prevention [15]. In 2011, a large study in

Denmark performed sub-group analyses of VKA vs ASA vs placebo by CHADS2

and CHA2DS2-VASc scores. The results showed no net

clinical benefit of ASA in patients with a low risk of stroke or embolism

(CHADS ≥ 0 or CHA2DS2-VASc ≥ 1). Conclusion

References

*Corresponding

author:

Citation:

Keywords