Research Article :

Gary L Murray and Joseph Colombo Over one billion people have Hypertension

(HTN); mortality and morbidity are increasing. The Parasympathetic and

Sympathetic (P&S) nervous systems prominently affect the onset and

progression of HTN, yet P&S measures are not used to assist in management. Our

objective was to determine the feasibility of HTN control using P&S-guided

to JNC 8 HTN therapy. 46 uncontrolled HTN

patients were randomized prospectively to P&S-assisted management,

adjusting JNC 8 therapy using the ANX 3.0 Autonomic Monitor and adding (r)

Alpha Lipoic Acid (Group 1) vs. JNC 8 (Group 2). The two Groups were similar

in: 1) age (mean 66 vs. 70 y/o for Groups 1 and 2, respectively; 2) initial

resting home Blood Pressure (BP, Group 1 mean=162/90 mmHg vs. Group 2 mean=166/87

mmHg, 3) initial resting office BP Group 1 mean=151/75 mmHg vs. Group 2 mean=155/73

mmHg, and 4) ethnicity. Upon follow-up (mean=8.35 mo.): 1) mean resting home

BPs were 145/77 mmHg (Group 1, 74% of patients at JNC 8 goal) vs. 155/83.5 mmHg

(Group 2, 30.4% at JNC 8 goal), and 2) mean resting office BPs were 138/71 mmHg

(Group 1) vs. 146/65 mmHg (Group 2). At the studys conclusion, Group 1

Sympathetic tone was lower than that for Group 2 both at rest and upon

standing, and Group 1 Parasympathetic tone was higher than that for Group 2

both at rest and upon standing. P&S-assisted HTN

therapy is feasible, resulting in improved BP control, through healthier

P&S tone on fewer prescription medications. Hypertension

(HTN) is the most common disorder seen in family practice, affecting over 25%

of primary care patients. Less than 50% of hypertensives are controlled, and

mortality as well as morbidity is increasing. While several causative

mechanisms of HTN have been elucidated, much investigation remains [1,2]. A neuroadrenergic cause is prominent: Increased Sympathetic

(S) tone and Cardiac

Output (CO) with low systemic vascular resistance (Rs) occur in

young hypertensives; eventually, the high CO and S-tone usually come down (3);

Rs increases, uncoupling it from S-tone; and decreased Baroreceptor

Reflex (BR), cardiopulmonary receptor sensitivity, and Parasympathetic (P) tone

are present, likely resulting from end-organ damage [1,3-8]. If P< Despite the involvement of Parasympathetic and

Sympathetic function in HTN, routine pharmacologic management of HTN is not

tailored for it, potentially contributing to reduced time in therapeutic range

that is inversely associated with all-cause mortality, resistant HTN, the 24%

HTN recidivism, as well as undesirable orthostasis and fatigue [12,13]. Additionally,

the increased oxidative stress that can contribute to the development of HTN and

ANS dysfunction is also not specifically addressed therapeutically. We, as have others, have found the potent, natural

antioxidant (r) Alpha Lipoic Acid ([r]-ALA) can reduce sitting systolic and

diastolic BP [14-16]. Therefore, our hypothesis is that pharmacologic HTN

treatment, adjusted for P&S

dysfunction when present treated with adjunctive (r)-ALA, could result in

improved P&S function and HTN control using fewer prescription medications.

The cost and side effects of treatment might be reduced. This is a prospective,

controlled, hypothesis- generating, feasibility study. In a suburban, mid-west cardiology clinic 46

consecutive patients (70% Female, average age 66 years, age range 33 to 88

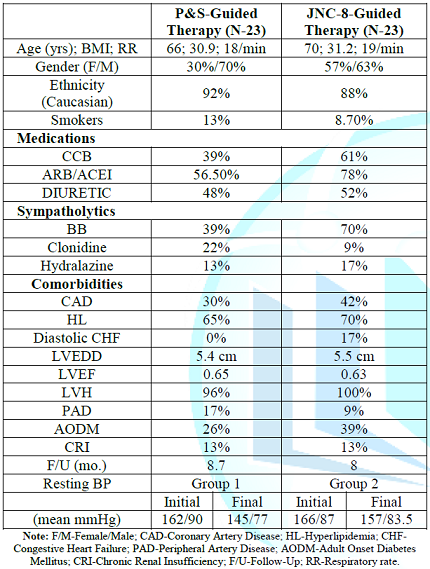

years, 92% Caucasian, see Table 1)

were recruited for this feasibility study. At baseline, all patients were under

standard care based on the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC-8) guidelines. At

baseline, all patients recruited: 1) Were treated but uncontrolled HTN (unmet

JNC goals) patients with any abnormality in P-and/or S-tone regardless of all

other vital characteristics, 2) Signed informed consent, and 3) Were randomly,

prospectively assigned to P&S-assisted therapy (Group 1) or JNC 8- guided

only therapy (Group 2). Table 1: Patient

Demographics. All patients were on a 2 gm. sodium diet and asked to perform

at least 2.5 hr. aerobic activity/wk. and to stop smoking. All patients with

obstructive sleep apnea were appropriately treated. P&S-assisted therapy

consisted of adjusting JNC 8 therapy as well as adding (r)-ALA per our usual

treatment for dysautonomia

in patients without HTN. The groups ages are similar: Group 1 averaged 66 y/o

and Group 2 averaged 70 y/o (p<0.001). The groups follow-up times are

similar: Group 1 averaged 8.7 months and Group 2 averaged 8.0 (p<0.001).

Five days of home morning and evening BP monitoring were collected. Each monitoring event recorded BP after 5 minutes of quiet

sitting and the data were averaged upon entry. Three days of b.i.d BPs were

averaged 2 months of adding (r)-ALA in Group 1, in order to allow it to take

full effect and monthly thereafter, whereas BPs were repeated 2 weeks after

entry in Group 2 and monthly afterwards. Physician measured BPs were never used

in this unblinded trial and doses of antihypertensive medications, along with

changes, were per JNC 8 guidelines in both groups; only the choice of

medication, the use of alpha lipoic acid, and the frequency of medication

change (less frequent in Group 1 since alpha lipoic acid requires at least 2

months for full effect, thereby excluding bias in favor of Group 1) differed Blood

pressure goals were identical: patient recorded home BPs that would meet JNC

goals. Office P&S testing measurements were taken with the ANX 3.0

autonomic monitor (TMCAMS, Inc., Atlanta, GA, USA, formerly ANSAR Medical

Technologies, Inc., and Philadelphia, PA, USA). P&S activity were computed

simultaneously and independently based upon concurrent, continuous

time-frequency analyses of Respiratory Activity (RA) and Heart Rate Variability

(HRV) [17-21]. P-activity (measured as the Respiratory Frequency area (RFa) is

defined as the spectral power within a 0.12 Hz-wide window centered on the

Fundamental Respiratory Frequency (FRF) in the HRV spectrum. FRF is identified

as the peak spectral mode of the time-frequency analysis of RA. Effectively, FRF is a measure of vagal outflow as it affects

the heart (a measure of cardio-vagal activity). S-activity (measured as the Low

Frequency area (LFa) is defined as the remaining spectral power, after

computation of RFa, in the low- frequency window (0.04-0.15 Hz) of the HRV

spectrum. High Sympathovagal Balance (SB=LFa/RFa) is defined as a resting ratio

>2.5, established in our 483 patient study [9]. P&S activity was

recorded from 5 mins of quiet sitting (normal ranges for both P&S at rest,

including sitting, is defined as 0.5-10 beats/minute2 [bpm2]).

The reported average SB is the average of the ratios of 4 second samples during

sitting, not a ratio of the averages. Cardiac Autonomic

Neuropathy (CAN) is defined as critically low, resting P-activity, RFa of <0.10

bpm2. High SB and CAN define a high risk of mortality, including:

acute coronary syndromes, congestive heart failure

or ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation alone or as a composite endpoint [9]. With

challenge (e.g., head-up postural change or standing), a normal S-response

(LFa) is defined as up to a 400% increase with respect to rest (e.g., sitting)

and a normal P-response (RFa) is a decrease with respect to rest. Follow-up BPs

and P&S measures were recorded 2 months after therapy adjustment in Group

1, whereas BPs were rechecked 2-4 weeks after adjustments in Group 2.

Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS v22.0. Dichotomous data were

analyzed using the chi-square test. A p-value of 0.05 or less was significant.

Student t-tests as two-tailed with equal variance. Although the two groups had similar initial BPs, home BP

control was more normalized in the P&S-assisted patients. After a mean f/u

of 8.35 mo., mean resting, home BPs were lower in Group 1 (145/77 mmHg, 74% 0f

patients at JNC 8 goal, mean pulse 61 bpm) vs. Group 2 (155/83.5 mmHg, 30.4% of

patients meeting JNC 8 goal, mean pulse 73 bpm; p<0.001 systolic, p= <0.001

diastolic, p<0.001 pulse). Similarly, Group 1 mean sitting office BPs were

138/71 mmHg vs. Group 2s 146/65 mmHg; p<0.001 systolic, p<0.001

diastolic. All Group 1 patients demonstrated at least 1 abnormal

autonomic measure initially, managed exactly as in normotensives, and improved

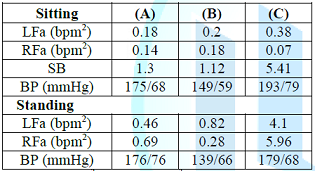

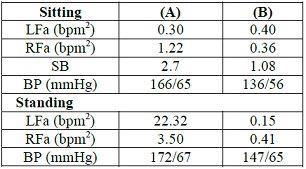

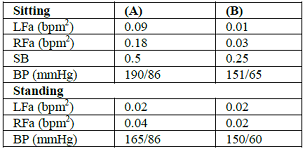

final office P&S measures (Table 2),

including: lower resting (sitting) S-tone (LFa=0.90, p<0.001), higher final

P-tone (RFa=0.71, p<0.001), and higher standing P-tone (RFa=1.56, p=0.005)

as compared with final Group 2 values were present. All of these differences

are consistent with improved HTN control. Prescribed sympatholytics influenced

the results. Initially, 6 of 23 (23%) Group 1 patients had low sitting S-tone

(LFa<0.5 bpm2) vs. 17 of 23 (74%) in Group 2, p<0.001. Group 2

had a higher percentage of patients prescribed sympatholytic. As a result, with P&S-Assisted therapy, all but one (5 of

6 or 83%) of the Group 1 patients with low resting S-tone improved vs. 9 of 17

(53%) of similar Group 2 patients, p<0.001. These improvements also reduced

the symptoms of fatigue and orthostatic hypotension

in these low resting S-tone patients. P-tone directly and indirectly affects

S-tone and thereby may affect BP. Low-resting P-tone may result in high resting

S-tone, since P-and S-tone typically variate reciprocally. High S-tone increases BR activity, attempting to lower BP;

low P-tone does the opposite. These opposing actions may increase difficulty in

controlling BP in hypertensives. Initially, 7 of 23 (30%) Group 1 patients had

low resting P-tone (<0.5 bpm2), vs. 15 of 23 (65%) Group 2

patients (p<0.001). Group 1 final P-tone increased in 4 of 7 (57%) patients with

low P-tone vs. Group 2 in which only 3 of 15 (20%) patients increased P-tone

(p<0.001). CAN is extremely low P-tone (<0.01 bpm2). CAN is

often associated with high SB. CAN with high SB is associated with increase

MACE risk [9]. Initially, no Group 1 patient presented with CAN, vs. 7 of 23

(30%) Group 2 patients (p<0.001). At the end of the study, 3 of 23 (13%)

Group 1 patients had CAN vs.5 of 23 (22%) with CAN in Group 2 (p=ns). A lower

S-tone in Group 1 is associated with a smaller, increased MACE risk of CAN [9].

High SB was demonstrated by 8 of 23 (35%) of the Group 1 patients vs.4 of 23

(17%) patients in Group 2 (p<0.001). SB was corrected (normalized SB) in 5

of the 8 (62.5%) high SB patients of Group 1 vs. no (0%) high SB patients of

Group 2 demonstrated normalized SB (p<0.001). High SB is a measure of (relatively) high resting S-tone. Combining

the resting S-tone results and CAN (very low P-tone) results, these findings

support the hypothesis that lower S-tone lowers the risk of CAN [9]. At the end

of the study, Group 1 patients had more patients with lower S-tone and patients

with lower CAN risk. Upon standing, 8 of 23 (35%) of Group 1 patients initially

had Sympathetic Withdrawal (SW, consistent with BR and cardiopulmonary receptor

dysfunction) vs. 12 of 23 (52%) of Group 2 patients (p=0.01). SW was corrected

in 5 of the 8 (62.5%) Group 1 SW patient vs. 4 of the 12 (33.3%) Group 2 SW

patients (p<0.003). Corrected SW indicates improved BR function. Inappropriately

increased P-tone (P excess, PE) upon standing (the normal change is to

decrease) initially occurred in 9 of 23 (39%) of Group 1 vs. 5 of 23 (21%) of

Group 2 patients (p=0.004). PE was corrected in 6 of 9 (67%) of Group 1 PE

patients and in 1 (20%) of the patients in Group 2 PE patients (p<0.001). However,

PE developed in 3 (21%) of the other Group 1 patients and in 2 (11%) of the

other Group 2 patients. Therefore, final PE was equally present (26%) in both

Groups. Probably PE indicates a compensatory mechanism (vasodilatation) to

increase blood volume thus attempting to maintain HTN. While increased standing P-tone lowers BP, a pronounced

increase can result in orthostasis, as can extreme SW. SB improved dramatically

in Group 1 patients from 3.26 to 1.86 (p=0.004, Table 2), despite fewer

patients using beta blockers, contrasted with essentially no change of SB in

Group 2. This is consistent with the difference in HTN control. Despite nearly

equal mean lower final S-and P-tone in Group 1, SB fell substantially, because

SB is reported as the average of ratios, rather than the ratio of averages. Since the final SB in both Groups was virtually equal, SB

cannot be inferred solely by the BPs which was significantly different. With

adjunctive P&S-guided therapy, home BP control was more normalized in Group

1 than without in Group 2: 134/77 mmHg vs. 155/83.5 mmHg, respectively

(p<0.001 for systolic BP and p<0.001 for diastolic BP). The two patient

groups were prescribed a mean of 2.3 vs. 3.0 prescription anti-hypertensives,

respectively. More Group 2 patients were prescribed Calcium Channel Blockers

(CCB) and at a higher daily mean dose (7.1 mg vs. 12.1 mg of Amlodipine for

Groups 1 and 2 respectively). Both groups were prescribed Beta Blockers (BB) at

similar mean doses, except for Carvedilol (40 mg for Group 1 vs. 32.5 mg for

Group 2). Both groups were prescribed Angiotensin Receptor

Blockers (ARB) or Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors (ACEI) at

similar mean doses, except for Losartan (100 mg for Group 1 vs. 50 mg for Group

2) and Lisinopril (40 mg for Group 1 vs. 22 mg for Group 2). More Group 1

patients took Clonidine at a lower mean dose (0.24 mg vs. 0.6 mg) and

Hydralazine was used similarly in both Groups (Table 1). Changes in medications

were as follows: 5 of 23 (22%) of Group 1 vs. 7 of 23 (30%) of Group 2 patients

were prescribed higher doses of medication; 14 of 23 (61%) of Group 1 vs. 100%

of Group 2 had a new drug introduced; 3 of 23 (13%) of Group 1 vs. 2 of 23 (9%)

of Group 2 were prescribed lower doses of medications and 17% of Group 1 vs. 9%

of Group 2 had a change of medication drug class. Group 1 took a mean dose of

761 mg (r)-ALA. This study demonstrates improved HTN BP control on fewer

prescriptions using adjunctive (r)-ALA in Group 1 (74% of patients at JNC 8

goal vs. 30.4% of Group 2 patients, p<0.001). We and others have shown (r)-ALA

can reduce resting BP and in this study concomitantly may assist lowering

standing BP [16,22]. Superficially, the medication administration profiles do

not explain the improvement in BP control, as more Group 2 patients took beta

blockers, CCBs, and ARB/ACEIs. It may be that (r)-ALAs favorable P&S

effects significantly contributed to better HTN control via S-and P-dependent

as well as its ANS-independent endothelial effects. Two Group 1 patients

normalized BP solely by taking (r)-ALA. Based upon P&S measures, 17% of Group 1 patients had a

change of drug class vs. 9% in Group 2. This likely was also beneficial. High

SB corrected in 71% of Group 1 patients vs. none in Group 2, contributing to

lowering HTN [22]. Amlodipine increases SB, while beta blockers and clonidine

decrease SB; beta-blockers and ARB/ACEIs improve BRS; and non-dihydropyridine

CCBs decrease BRS [22-27]. (r)-ALA is a powerful natural antioxidant that

improves P&S function including BRS, nitric oxide levels, and endothelial dysfunction

[15,16,22,28]. Sympathetic Withdrawal upon standing results in compensatory

mechanisms to preserve perfusion of vital organs that include increasing

S-tone, both supine and sitting. This exacerbates HTN, thereby causing its control to be more

difficult. Sympatholytics, therefore, can worsen SW (only clonidine has a

minimal adverse effect as it increases BRS [24,25,29]. Group 1 patients

significantly improved SW. This is consistent with improved BRS, probably by

(r)-ALA and higher doses of Lisnopril and Losartan. P-excess (PE) upon standing

is indicative of ANS dysfunction, and 9 of 23 (39%) of Group 1 vs. 5 of 23

(22%) of Group 2 patients initially displayed PE. PE may also trigger

compensatory measures, including secondary S-excesses that increase BP. The central alpha action of Carvedilol, Low Dose Serotonin

Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRI), as well as Tricyclics (TC) may help to reduce

PE. One Group 1 patient normalized PE and HTN with addition of (r)-ALA alone. Resting

P&S measures were utilized in choosing medications as follows. If P&S

balance (as measured by SB) was normal, then any anti-hypertensive was

prescribed. If SB was high due to a relative, resting S-excess), then

sympatholytics were chosen or adjusted. If SB was high due to low P, then

sympatholytics were avoided and an ARB/ACEI and/or Diltiazem were chosen or

adjusted. High dose (r)-ALA may increase resting P-activity and thereby lower

SB. Upon standing, if SW was absent, then any antihypertensive was prescribed. If

SW was demonstrated, then sympatholytics were avoided (excepting Clonidine) as

was Diltiazem and Amlodipine, Hydralazine and/or high dose (r)-ALA prescribed. Diuretics were utilized only for dependent edema, since

intravascular volume needed to be maintained. Low dose ARB/ACEI also might be

prescribed. If PE presented, again intravascular volume should be preserved, so

diuretics were avoided. Since an increase in S-activity is a compensatory

mechanism to combat orthostasis, sympatholytics were avoided (except low dose

carvedilol whose central alpha action reduces P-tone and possibly clonidine).

Amlodipine is a good choice only if S-tone isnt high, since it increases

S-activity. Adjunctive low dose TC or SSRI would have useful to reduce

P-activity, but we confined our therapy to traditional anti-hypertensives. The

uncoupling of P&S function to Rs in HTN results in variable

P&S profiles. Anti-hypertensives have variable P&S effects. Consequently,

knowledge of S-and P-tone is essential for choosing the best anti-hypertensive

drugs and (r)-ALA enhances their effectiveness, given (r)-ALAs ANS antioxidant

effect which reduces ANS dysfunction secondary to the increased oxidative

stress associated with HTN, chronic diseases and

the aging process (Tables 3, 4 and 5

are illustrative). P&S-assisted treatment of HTN, with adjunctive (r)-ALA

for dysautonomia is feasible and results in more normalized BP control within

one year. Our hope is that reduced long-term medication costs, mortality, and

morbidity will follow if BP control is sustained. A randomized, prospective

clinical outcome study should be dome. These results are short-term, single center, in 46 patients. Our

accent was specifically lowering SB. Reducing standing PE with low dose TCs or

SSRIs could have improved BP control further. 1.

Carthy E. Autonomic dysfunction in essential

hypertension: A systematic review (2014) Ann Med Surg 3: 2-7. 2.

Erdine S and Aran S. Current status of hypertension

control around the world (2004) Clin Exp Hypertens 26: 731-738. https://doi.org/10.1081/ceh-200032144

3.

Amerena J and Julius S. The role of the autonomic

nervous system in hypertension (1995) Hypertens Res 18: 99-109. https://doi.org/10.1291/hypres.18.99

4.

Grassi G, Seravalle G and Quarti-Trevano. The neurogenic

hypothesis in hypertension: current evidence (2010) Exp Physiol 95: 581-586. https://doi.org/10.1113/expphysiol.2009.047381

5.

Grassi G and Mancia G. The role of the sympathetic

nervous system in essential hypertension (1995) Ann Ital Med Int 10: 115S-120S. 6.

Grassi G. Autonomic nervous system in arterial

hypertension (2001) Ital Heart J Suppl 2: 850-856. 7.

Mancia G and Grassi G. The autonomic nervous system

and hypertension (2014) Circ Res 114: 1804-1814. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.114.302524

8.

Chang P, Kriek E and Van Brummelen P. Sympathetic

activity and presynaptic adrenoceptor function in patients with longstanding

essential hypertension (1994) J Hypertens 12: 179-190. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004872-199402000-00011

9.

Murray G and Colombo J. Routine measurements of cardiac

parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems assists in primary and

secondary risk stratification and management of cardiovascular clinic patients

(2019) Clinical Cardiol Cardiovascular Med 3: 27-33. https://doi.org/10.33805/2639.6807.122

10.

Pal G, Pal P, Nanda N, Amudharaj D and Adithan C. Cardiovascular

dysfunctions and sympathovagal imbalance in hypertension and prehypertension:physiological

perspectives (2013) Future Cardiol 9: 53-69. https://doi.org/10.2217/fca.12.80 11.

Seravalle G and Grassi G. Obesity and hypertension

(2017) Pharmacol Res 122: 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2017.05.013 12.

Doumas M, Tsioufis C, Fletcher R, Amdur R, Faselis C,

et al. Time in therapeutic range, as a determinant of all-cause mortality in

patients with hypertension (2017) J Am

Heart Assoc6: e007131. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.117.007131

13.

Sandhu A, Ho P, Asche S, Magid D, Margolis K, et al. Recidivism to uncontrolled blood pressure in

patients with previously controlled hypertension (2015) Am Heart J 169: 791-797.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2015.03.012 14.

De Champlain J, Wu R, Girouard H, Karas M, EL Midaoui

A, et al. Oxidative stress in hypertension (2004) Clin Exp Hypertens 26: 593-601.

https://doi.org/10.1081/ceh-200031904

15.

Su Q, Liu J, Cui W, Shi X, Guo J, et al. Alpha lipoic

acid supplementation attenuates reactive oxygen species in hypothalamic

paraventricular nucleus and sympathoexcitation in high salt-induced

hypertension (2016) Toxicol Lett 241: 152-158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxlet.2015.10.019

16.

Boccardi V, Taghizadeyh M, Amirijani S and Jafamejad

S. Elevated blood pressure reduction after alpha-lipoic acid supplementation: a

meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (2019) J Hum Hypertens. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41371-019-0174-2

17.

Aysin B, Colombo J and Aysin E. Comparison of HRV

analysis methods during orthostatic challenge: HRV with respiration or without?

(2007) 29th Int Conf IFFF EMBS Lyon, France. https://doi.org/10.1109/iembs.2007.4353474

18.

Akselrod S, Gordon D, Ubel F, Shannon D, Berger A, et

al. Power spectrum analysis of heart rate fluctuation: a quantitative probe of

beat-to-beat cardiovascular control (1981) Science 213: 220-222. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.6166045

19.

Akselrod S, Gordon D, Madwed J, Snidman N, Shannon D,

et al. Hemodynamic regulation: Investigation by spectral analysis (1985) Am J

Physiol 249: H867-H875. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.1985.249.4.h867

20.

Akselrod S, Eliash S, Oz O and Cohen S. Hemodynamic

regulation in SHR: investigation by spectral analysis (1987) Am J Physiol 253: H176-H183.

https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.1987.253.1.h176

21.

Akselrod S. Spectral analysis of fluctuations in

cardiovascular parameters: a quantitative tool for the investigation of

autonomic controls (1988) Trends Pharmacol Sci 9: 6-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-6147(88)90230-1

22.

Ogura C, Ono K, Myamoto S, Ikai A, Mitani S, et al.

L/T-type and L/N-type calcium-channel blockers attenuate cardiac sympathetic

nerve activity in patients with hypertension (2012) Blood Press 21: 367-371. https://doi.org/10.3109/08037051.2012.694200

23.

Baum T and Shropshire A. Susceptibility of spontaneous

sympathetic outflow and sympathetic reflexes to depression by clonidine (1977) Eur

J Pharmacol 44: 121-129. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-2999(77)90098-x

24.

Yee K and Struthers A. Endogenous angiotensin 11 and

baroreceptor dysfunction: a comparative study of losartan and enlapril in man (1998)

Br J Clin Pharmacol 46: 583-588. 25.

Heesch C, Miller B, Thames M and Abboud F. Effects of

calcium channel blockers on isolated carotid baroreceptors and baroreflex (1983)

Am J Physiol 245: H653-H661. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.1983.245.4.h653

26.

Floras J, Jones J, Hassan M and Sleight P. Effects of

acute and chronic beta-adrenoceptor blockade on baroreflex sensitivity in

humans (1988) J Auton Nerv Syst 25: 87-94. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1838(88)90013-6

27.

Queiroz T, Guimaraes D, Mendes-Junior L and Braga V. Alpha-lipoic

acid reduces hypertension and increases baroreflex sensitivity in renovascular

hypertensive rats (2012) Molecules 17: 13357-13367. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules171113357

28.

Murray G and Colombo J. (r)Alpha lipoic acid is a

safe, effective pharmacologic therapy of chronic orthostatic hypotension

associated with low sympathetic tone (2018) Int J Angiol 00: 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0038-1676957

29.

Guthrie G and Kotchen T. Effects of prazosin and

clonidine on sympathetic and baroreflex function in patients with essential

hypertension (1983) J Clin Pharmacol 23: 348-354. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1552-4604.1983.tb02747.x

Gary L Murray, The Heart and Vascular Institute, 7205 Wolf River

Blvd, Germantown, TN, 38138, USA, Tel: +1 901-507-3100, Fax: +1 901-507-3101, E-mail:

drglmurray@hotmail.com Murray LG and

Colombo J. The feasibility of blood pressure control with autonomic-assisted hypertension

therapy versus JNC 8 therapy (2020) Clinical Cardiol Cardiovascular Med 4: 1-5. Hypertension, Parasympathetic nervous system, Sympathetic nervous system, Autonomic nervous system.The Feasibility of Blood Pressure Control with Autonomic-Assisted Hypertension Therapy Versus JNC 8 Therapy

Abstract

Background: Full-Text

Introduction

Methods

Results

Discussion

Conclusions

Limitations

References

Corresponding

author

Citation

Keywords