Review Article :

Howard Moskowitz, Attila Gere, Yeshaya Danny Moskowitz,

Robert Sherman, Yehoshua Deitel,

Divya Nagarajan and Petraq

Papajorgji This paper introduces a new approach to understanding the mind of the customer with the goal of optimizing the supply chain by creating, marketing and then delivering what the customer(s) want. The underlying notion is that for every product one can discover groups of people with defined preferences for the product and defined messages which drive expected purchase. The approach divides into two parts, knowledge development through Mind Genomics experiments and mind-set sequencing through the PVI (Personal Viewpoint Identifier). The paper shows data for six flavored beverages, the creation of mind-sets and the creation of the PVI to drive the messaging and thus purchase of each product. The paper finishes with the prospects for the world of product design and marketing when one can rapidly discover these product-specific mind-sets and the messages which excite each mind-set. One could fill book after book with

what we know about consumer preferences, ranging from simple tests of acceptance

for specific products, to patterns of preferences for lifestyles [1-3]. The knowledge

for such books emerges from business focus on a specific product, all the way to

grand strategies for general marketing efforts and to the academic investigation

of what consumers find interesting [4]. A great deal has been written about what

consumers want, their preferences and even aspects of what we might call cognitive

economics [5,6]. Most of these segmentation schemes

work from the top down, dealing either with whom the respondent IS, the pattern

of what the respondent does or how the response answers a detailed questionnaire

about general attitudes towards many topics. There is little in the way of a bottom-up

approach, with actionable knowledge emerging from specific topics, such knowledge

then integrated into a larger structure of general knowledge. Or, if there is integrated

knowledge basis going from the granular to the general, the knowledge base has not

been shared with the general public. The lure of knowledge to provide a competitive

advantage is increasing, year by year, with the massive increase in the ability

to collect data (e.g., the internet of things, the shopping baskets, the purchase

patterns of people), the decrease in cost to store and retrieve information about

purchases and the exploding power of data analytics which correlate

the data with publicly available information about a person. The temptation is to

rely increasingly on data science, on so-called business analytics, with the rationale

that the answer must be in there. In the world of foods, we see an increasing number

of supermarket chains making use of the information to understand trends in food.

What took months with Nielsen audits now takes minutes. The question, however, is

how to move from these lakes of data, masses of information in which one hopes the

treasures of knowledge swim, into an actionable world of business decisions. It

is no longer acceptable or even reasonable to wait months to analyze data, in the

hopes of finding something which may allow a competitive advantage, no matter how

temporary. Recent advances in computer technology,

modeling, artificial

intelligence and data acquisition by the grocery trade promises a new age for understanding

the consumer. The new era of knowledge about the consumer can be described as from

the outside in. That is the newly emerging technology can track what the supermarket

customer looks at and what they buy [7-9]. When the shopping occurs on-line, it

is easy to measure the response of the customer by what the customer chooses in

the path, i.e., the click and note exceptions to typical behaviors [10]. Furthermore, the customers previous

behavior may be analyzed to suggest the next items to be purchased [11]. These advances

promise a new era of understanding the shopper first to the usually small group

of early adopters who try new technologies and then later to the world of the supermarkets

themselves, who take comfort in seeing others do the experimentation [12]. What

is missing from all these efforts, these technological breakthroughs, is foundational

knowledge about the mind of the customer. That is, the analyses can track eye movements,

record market basket contents, measure clicks and by so doing get a sense of what

is actually happening and what external, measurable factors co-vary with each other.

But the failure is the lack of knowledge about the mind. The measures are similar

to the efforts of Skinner, starting almost 80 years ago, at Harvard University and

John B. Watsons efforts years before that. These Behaviorists in the world of psychology

ignored the mind of the person (or animal), measured regularities in behavior and

deduced what might be happening. They would not and could not understand the mind,

relegating themselves as they did to observing externalities and hypothesizing. Of course,

the animals with which they worked could not be interviewed to report what they

were thinking. As the grocery trade moves towards

accepting new technologies in the increasingly competitive space of food sales,

it is important to move towards a greater discipline in the knowledge we obtain

and use. The knowledge-building efforts should create a competitive advantage for

the current scenario and for new scenarios evolving through technology, through

changes in product design, through changes in the competitive frame and most important, through the ever-present change

in patterns of consumer preferences. What is a competitive advantage today in technology

may become simply yesterdays news as competitors leapfrog one another at a pace

which accelerates week-by-week. It no longer suffices to remain within ones comfort

zone with the reassuring but deadly platitude which served so often in the past,

namely people always have to eat. During the past decades, a new science

has emerged to help the supply chain. The science is known as Mind Genomics. The

underlying notion of Mind Genomics is that each person experiences daily life as

a series of small experiences, reacting to different aspects of those experiences.

When we map out those experiences, whether behavioral situations or information

(messages) we discover regular or systematic individual-differences among people.

The result is a structured science to approach the mind of people confronting the

every day. The contribution of the Mind Genomics effort is a tool by which to increase

the effectiveness of business communications by putting consumer mental demand into

the supply chain as a key driver of upstream activities. The thesis of this paper is that the

supply chain may profitably begin with a deeper understanding of the last step,

the person who buys the product and consumes it, whether the consumption be preparing

it, eating it, or feeding to another. When we know that final step in depth, there

is the possibility of a new form of supply chain optimization – reaching

from the end of the chain, the customer/consumer, to the start of the chain, the

production and even to the product design and product planning. The problem is simple,

one faced by every food manufacturer on the one hand, or the food wholesaler/retailer

on the other. We illustrate the problem and Mind Genomics solution by a typical

case history. The topic is the creation and selling of a new set of flavored beverages

by a company which wishes to take advantage of the increasing penchant of consumers

to explore the sensory characteristics of beverages beyond the initial limited array

of flavors available only decades ago. The veritable explosion of flavors, so well

documented by popular science writer Malcolm Gladwell in his TED Talk, Choice, Happiness

and Spaghetti Sauce, has led to a public, searching for new

experiences a lot of the time which explores sensory experience, choosing new ones

all the time [13]. Indeed, rather than a limited array of less than optimal alternatives

today we have what has been called the Paradox of Choice, wherein so many SKUs,

shop-keeping units, are launched in order to gain shelf space. All too-often the

pell-mell introduction of flavors backfires [14]. Let us look at how a company might

approach marketing the above-mentioned flavored beverages, spanning the range of

beer, cider, tequila, low alcohol beverage, hot coffee and ice coffee, respectively.

The objective is with knowledge of the consumer, not yet developed, to message correctly

and most important, drive the right message to the right person. We assume that

the products have already been developed. The formal problem is simple to state.

We are considering the customer as a destination into which we put a product. We

treat the customer as possessing a set of sensitivities toward each product, whether

or not the customer is involved with the product. The sensitivities are to specific

messages which attract the customer to the product or push the customer away from

the product. Our objective to move the product to this receptacle, with the assumption

that once the product reaches the consumer it will be consumed and thus the product

journey will end. Most marketers and product developers would react in disbelief

to the statement. It is as if we are treating the consumer as something whose dynamics

are known, a simple but final conduit to our set of products. So much of marketing

is a deep discussion of what consumers want, when they want it and the dynamics

of competition that we seem to reduce the very humanness of a consumer to a set

of factors to be determined and then expect the optimum to occur the product to

be accepted. How can the depth of the customer experience be captured by a series

of messages, much less messages which are determined through science, experimental

design and simple experiments? Most optimization efforts assume the

real problem in optimization is to identify WHAT to do. Here, with consumers, we

may not even know either what to do or what to say. What are the features of the

product which the consumer wants? When we solve that, what should the marketer say

about the product to convince the buyer? This part of the supply chain, the ultimate

buyer, has a mind of its own. The consumer can simply say NO. It is the emerging

science of Mind Genomics to which we now turn. We assume zero knowledge for marketing,

rather than assuming the marketer or advertising agency knows the single best message

to drive purchase. One way to identify messages which work consists of mixing and

matching message, present these mixtures to the person, get the reaction and determine

which particular messages in the mix are responsible for the YES, the answer by

prospective customers that, YES, I want that product. Mind Genomics refers to a young science,

about 30+ years by now, at the time of this writing (fall, 2019). Mind Genomics

emerged from the efforts of experimental psychologists and marketing academics to

understand the way people made decisions, moving beyond simply asking the people

to describe their criteria, not always easy and often not at all possible. Rather

than asking a person to reflect on HOW and WHY a specific decision is arrived at,

Mind Genomics implements

small experiments, on the computer to establish a causal relation. The respondent

reads different vignettes or sets of messages, about a product or service and rates

the vignette on some type of simple anchored scale, the Likert scale [15,16]. The

analysis reveals what features of the vignette drive the decision, reveals new groups

(mind-sets) and shows how to discover those mind-sets among new people who had not

participated in the study. The test materials of Mind Genomics phrases, known as

elements or messages, are mixed according to experimental design to create a set

of prescribed combinations. The same element appears several times

in combination with other of elements. After reading each individual combination

the respondent integrates all the information in the vignette and assigns a single

rating. The process is quick, lasting often only 1-2 seconds. Regression analysis

deconstructs the individual contributions of each element, respectively, creating

an additive model. The coefficients of the model or equation are the part-worth

contribution, interpreted as the importance of each element to the respondent. Typically,

the respondent is not even aware of his or her individual weighting scheme, but

generally the data make intuitive sense to the respondent when the respondent is

shown the coefficients of the one-person model emerging from his or her own ratings.

One feature of Mind Genomics worthy of special mention is the attention given to

ease of set-up, speed of data acquisition and rapidity of analysis and reporting,

all facilitated by todays (2019) technology, Smartphones and a simple app called

BimiLeap (www.BimiLeap.com).

The app leads the respondent through the sequence of ideation, study setup and moves

to respondent acquisition through a link and associated sample providers for respondents.

The app finishes with an automatic analysis done with 2-3 minutes of the end of

the study. The output is a Microsoft Powerpoint® report of the results in a formatted

template, ready for immediate use and publication. We now move to the experiment which

provides the necessary data. The data from this study were collected more than ten

years before, funded by the Wild Corporation, a flavor supplier, under the name

Drink It! We report the data, show the results and then show the PVI for the six

products and representative mind-set membership data for two respondents on each

of the six flavored beverages after the two respondents each used the PVI. Step

1-Define the topic and select the beverages: The topic

is what drives interest in buying a beverage for consumption. The original study

(Drink It!) funded by Wild Flavors and focused on 30 beverages, with a goal to understand

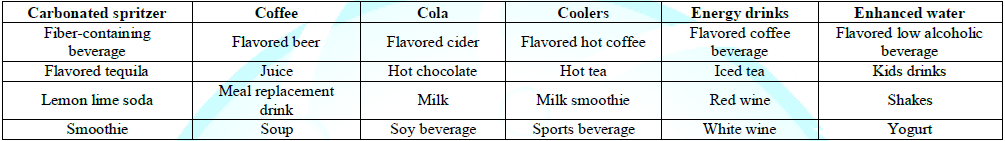

the broad spectrum of drivers of interest in the beverage category. (Table 1) shows the beverages. The six flavored

beverages are those chosen to demonstrate the creation

of the six-beverage PVI and its deployment. They are shown in the shaded cells. Table

1: The 30 beverages tested in the Drink It! Project. (Courtesy

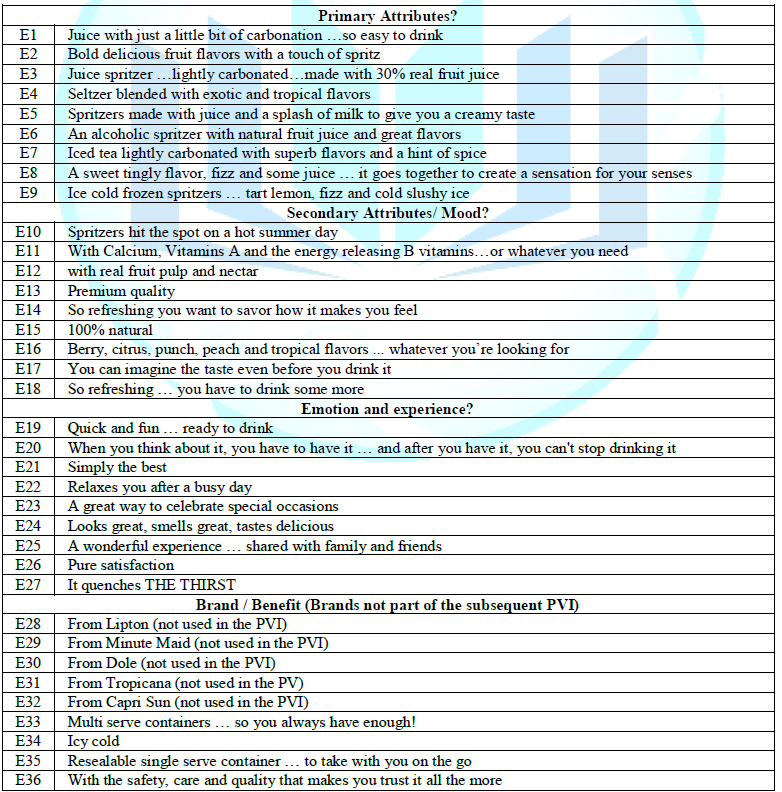

of It! Ventures, Inc.) Step 2-Develop the

structure of messages that will be used to identify what to say: The structure of the

It! Studies was set up to investigate four questions, and nine answers to each question.

(Table 2) shows an example of these elements

for one product, juice spritzer. Step 3-Run relatively

small-scale studies and extract mind-sets from each study: The actual Mind Genomics

process is straightforward. A basic experimental design is developed so that each

of the 36 elements or answers appears an equal number of times, in this case five

times. The experimental design for this specific array of questions and answers

(4x9) generates 60 combinations or vignettes, each vignette comprising 2-4 elements

or answers, at most one answer from a question in each vignette. That is, the vignettes

are not always complete, since some vignettes comprise three elements and other

vignettes comprise two

elements. The experimental design ensures that all 36 elements are statistically

independent of each other, allowing for regression analysis to relate the presence/absence

of each of the 36 elements to the rating. The incompleteness of the design further

ensures that statistical independence, so that the coefficients from the regression

model (explained below) have ratio-scale properties. The underlying experimental

design produces 60 combinations, tested by a single respondent. The next respondent

receives vignettes, the combinations, created by the same experimental design, but

for this new respondent the combinations are changed. The strategy called permuted

experimental design ensures that the experiment tests many, if not most of the possible

combinations that can be created [17]. The strategy of Mind Genomics thus differs

from the strategy of other studies using experimental design. Mind Genomics permutes

the combinations. The knowledge about how people respond comes from a wide range

of different test vignettes, i.e., a fuller picture not from a limited number of

test vignettes evaluated by many people, i.e., a less noisy but far more incomplete

picture. Step 5-Create mind-sets

by clustering: The

mind-sets for a beverage are simply those people whose patterns of responses to

the 36 elements for a beverage are similar. We can think of these mind-sets as mental

primaries for the beverage, primaries which emerge when we have a reasonable number

of respondents participating. The approaches to developing these primaries have

been described in detail elsewhere [18]. We need only keep in mind that to discover

these primaries we apply the well-accepted statistical procedure of clustering to

the respondents in each study, dividing the respondents into homogeneous groups, based

upon the pattern of their 36 coefficients for that beverage. Clustering is a well-accepted

statistical method which creates groups of objects (people), based upon a definition

of distance, specifically distance between two profiles of coefficients k1

- k36. Clustering is the general name given to a set of statistical procedures

which divide objects, our respondents, into groups with the property that the patterns

of the 36 coefficients are similar to each other within a cluster and the pattern

created by the average of all respondents to create 36 average coefficients are

very different from cluster to cluster [19]. In the language of Mind Genomics, the

clusters are mind-sets (Table 3) shows

the six sets of coefficients for three mindsets, one set for each flavored beverage.

For each study we pulled out three mind-sets, shown in columns labelled MS1, MS2,

and MS3, respectively. We sort each table, first by MS1, then by MS2, then by MS3,

respectively. All coefficients of 9 and above are shaded. It is clear from Table

3 that the mind-sets differ and can be interpreted by looking at the coefficients

that are darkened. For table 3 please go through the below link Step 6-For each beverage;

create a PVI (Personal Viewpoint Identifier): The objective is to assign a new person

to the appropriate mind-set, for each beverage. Up to now, we have looked at the

respondents who participated in each study in terms of who they say they ARE (e.g.,

age, gender product usage and so forth). The discovery of mind-sets produces a new

way to define who a person is, namely the pattern of elements to which the person

responds, i.e., the mind-set. The only problem is that people cannot easily tell

an interviewer who they are in terms of the mind-set with respect to a product.

They may know, but most likely they have never even thought of mind-sets with respect

to the product. It becomes vital to create a simple tool, a PVI, which can quickly

assign a NEW person to one of the two or three mind-sets for a specific beverage,

these mind-sets empirically uncovered in a Mind Genomics experiment. A

variety of statistical tools have been developed to assign objects to predefined

groups. These tools use the property of the objects along a vector of different

variables to create a classification tool. The tool weights the individual variables

and combines them. The result is then a number or set of numbers which map to one

of the clusters, defined as the most appropriate cluster for the pattern of responses.

The tools require the raw data and statistical back testing. The most common of

these is known as DFA, discriminant function analysis [20]. Often, however, we only

have the summary data, such as the profiles in Table 3. Authors Gere and Moskowitz

have developed an algorithm which uses Monte Carlo simulations

and response patterns to assign a new individual to one of the mind-sets or cluster.

The tool, PVI, allows presents the respondent with six questions taken from the

most discriminating elements from the study. The questions are selected after a

Monte Carlo simulation of 20,000 data sets, based upon the original data, but perturbed

with noise. The

outcome is a set of six questions, each answered by the same two answers, appropriate

for the product. The six questions generate 64 possible patterns. Each of the 64

possible patterns maps to one of two mind-sets, or where appropriate, one of three

mind-sets. Figure 1 shows part of the

PVI for this study. Figure 1 show three of the six sets of questions The PVI begins

with requisite information about the respondent and two opt-ins. The full PVI continues

with six sets of questions, one set for each study. The PVI varies the order of

studies across participants and the order of questions within a study. In this way

the PVI attempts to minimize order bias. The PVI takes about 30-45 seconds for the

up-front basic information and about 15-20 seconds for each product. The full set

of six products thus takes about 2-3 minutes. As in all on-line studies, it is best

to offer an incentive to the respondent to participate. Otherwise, the process to

obtain many respondents can take days or weeks, rather than minutes and hours. The

PVI returns with six records for each respondent, one record for each product and

each respondent, as shown in (Table 4).

The PVI data is laid out in the form of a flat file, with the relevant information

about each respondent and each product as a separate record. Each respondent generates

six records. The flat file allows individual analyses of each product, as well as

subsequent creation of a master record for each respondent. The PVI has no place

for the respondent name. The respondent is identified by name or home address. The

respondent is completely informed about the data being collected. The respondent

can opt-out entirely, or opt-in but request no further contact. Every effort is

made to adhere to the current privacy rules [21]. The

vision of the PVI is not simply a set of typing tools, allowing the consumer researcher

to assign a given individual to a set of different mind-sets, based upon the pattern

of ratings. Such a limited vision would constrain the use of the PVI to marketing

efforts. The

reality is that the combination of Mind Genomics with the PVI offers dramatic advances

for our understanding of the human mind. Beyond this understanding is the looming

an enticing prospect of correlating the mind of people (pattern of mind-sets) with

other behaviors and even with physiological features such as genes. It is worthwhile

exploring the potential in a bit of detail. We begin with the precursor of the PVI,

BimiLeap and a do-it-yourself technology to understand the mind of people. The

data reported above come from a precursor of BimiLeap, a technology known as Idea

Map. BimiLeap is an accelerated, simplified, inexpensive and far more rapid tool,

which can be set up, deployed and full results obtained in a matter of a few hours.

Todays BimiLeap technology has been optimized for four questions, each with four

answers rather than nine answers, in the interest of speed, cost and ease. The BimiLeap

project follows a series of simple steps, paralleling the approach but in a do-it-yourself

format. The study for a single topic (e.g., any topic) begins with the statement

of the topic, the creation of four questions and four answers to each question.

The BimiLeap program makes it easy to set up the study on a smartphone or on a computer

or laptop. The

program then requires the researcher to write an introduction to the respondent

about what is expected and provide a rating scale. Finally, the researcher selects

the target population, pays by credit card, the study is launched and each respondent

who participates evaluates 24 unique combinations. The analysis is the same as presented

here, with the addition of modeling both for the rating and for the response time

between the presentation of the stimulus and the rating assigned. The results are

returned in 1-2 minutes after the end of the fieldwork. The results, sent by email,

comprise templated, pre-formatted Microsoft PowerPoint® presentation with the data

incorporated and the tables and raw data in an accompanying Microsoft Excel® file. The

speed of the set-up and data acquisition, often within a few hours for a single

study, make it possible for the researcher to deeply investigate an entire vertical,

comprising 2-20 or more topics, related to each other, either in terms of alternatives

(e.g., types of products in a supermarket), or in terms of what researchers call

The journey (e.g., sequence of activities in ones from entering a hospital to discharge,

from entering school on the first day to leaving school on the last day). Each study

may require as few as 100 respondents and can be completed within the aforementioned

2-4 hour time span. The

final activity, creating the PVI for the 2-20 topics in a vertical, takes 3-4 hours,

launching the PVI takes five minutes. Deployment a matter of distributing the PVI

to the correct individuals who will participate. What

then does this capability of Mind Genomics +PVI mean for science and for application? · At the very simplest

level, the above-mentioned process produces an integrated library of data for a

vertical, with the information archived, relatable to each other in terms of metrics.

· The next level comprises

the analysis of alternative populations by the PVI to understand the distribution

of mind-sets under different situations, whether these situations be geography,

culture, health versus disease, economics and so forth.

The sheer simplicity of implementing the PVI with todays communications makes it

reasonable to obtain millions, tens of millions, or even hundreds of millions of

respondent. The consequence is a rich database of the mind of people, at one time,

with the ability to identify the covariation of mind-sets with exogenous factors

(age, gender, market, behavior) across many different, related topics, in the vertical.

In other words, for food, the mind-set of 100 million people versus who they are

and versus what they purchase. · At an even deeper

level, with services specializing in genetic typing, there may be a way to relate

genetic profiles of people to mental profiles obtained from the PVI and the two

of them to behavior. The PVI is the missing piece, as is the need to scale up the

data acquisition to millions. It is the PVI, the operational structure of the mind

in terms of RELEVANT topics which is the linchpin, holding both

sides together, the measured genetic profile and the behavioral and social profile. Attila Gere thanks the support of the Premium

Postdoctoral Research Program of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. The authors

acknowledge the original assistance of Dr. Hamid Faridi and Ms Marianne Gillette

of the McCormick and Company, for their early support of the It! Studies. The authors

acknowledge the early support of the Wild Flavors Company, for the funds and encouragement

to conduct the Drink It! Study, from which the data in this paper were extracted.

The authors acknowledge the early support of Ms Hollis Ashman and Ms Jacqueline

Beckley (The U&I Group, Inc.) for the early analyses of the Drink It! Data.

The authors thank Dr. Philip Perkins for his ongoing moral support of the entire

It! Effort. We

have focused this paper on the supply chain for food because the original challenge

of the PVI and the BimiLeap technologies were posed to the authors by the manufacturers

of food as far back as 2001. The original request was made to author Howard Moskowitz

by the Dr. Hamid Faridi and Ms. Marianne Gillette of the McCormick Company, to use

Mind Genomics to identify the patterns of product features driving acceptance in

a set of 30 products. In 2008 Howard Moskowitz was requested by Dr. Philip Perkins

of Bush Brothers Inc., to use the same technology to understand the entire range

of foods in a store, in order to drive increased purchase through targeted messaging.

It would take several years for the PVI to be developed, finding preliminary use

in foods, but then enjoying a modest but growing demand in the finance industry,

the insurance industry and finally the hospital business with its relentless focus

on patient satisfaction and patient compliance. 1.

Brower

M. Claritas (formerly Nielsen) Segmentation and Market Solutions (2017) Charleston

Advisor 18: 15-20. https://doi.org/10.5260/chara.18.4.15 2.

Weinstein

A and Cahill DJ. Lifestyle Market Segmentation (2014) CRC press, United States. 3.

Wells

WD. LifeStyle and Psychographics (2011) Marketing Classics Press, USA. 5.

Kahneman

D and Egan P. Thinking, Fast and Slow (2011) Farrar, Straus and Giroux, United States. 6.

Moskowitz HR and Gofman A. Selling Blue Elephants: How

to Make Great Products that People Want Before They Even Know They Want Them (2007)

Pearson Education. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5885.2008.00327_3.x 7.

Cowburn

G. The Front of Pack Nutrition Information Panel: Using Novel Methods to Explore

Consumer Decision Making at Point of Choice during Routine Supermarket Shopping

(2016) PhD Dissertation, University of Oxford, UK. 8.

Turow

J. The aisles Have Eyes: How Retailers Track Your Shopping, Strip Your Privacy and

Define Your Power (2017) Yale University Press, United States. 9.

Sigurdsson

V, Larsen NM and Fagerstrøm A. Behavior Analysis of In-Store Consumer Behavior (2016)

Routledge Comp Cons Beh Anal 40-50. 10.

Huyghe E, Verstraeten J, Geuens M and Van Kerckhove A.

Clicks as a Healthy Alternative to Grocery Shopping Reduces Vice Purchases (2017)

J Marketing Res 54: 61-74. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmr.14.0490 11.

Londono

JC and Castano R. Supermarket suggested shopping lists (SSSL), Promotions and Grocery

Purchases (2017) Int Rev Ret Distri Cons Res 27: 146-163. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2017.1288650 12.

Faulds

DJ, Mangold WG, Raju PS and Valsalan S. The Mobile Shopping Revolution: Redefining

the Consumer Decision Process (2018) Business Horizons 61: 323-338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2017.11.012 13.

Gladwell M (2004)

Ted Talks. 14.

Schwartz

B. The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less (2004) Harper Perennial, United States. 15.

Green PE and Srinivasan V. Conjoint Analysis in Marketing:

New Developments with Implications for Research and Practice (1990) J Marketing

54: 3-19. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299005400402 16.

Moskowitz

HR, Gofman A, Beckley J and Ashman H. Founding a New Science: Mind Genomics (2006)

J Sen Stu 21: 266-307. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-459x.2004.00066.x 17.

Gofman

A and Moskowitz H. Isomorphic Permuted Experimental designs and their application

in Conjoint Analysis (2010) J Sensory Studies 25: 127-145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-459x.2009.00258.x 18.

Moskowitz

HR. Mind Genomics: The Experimental Inductive Science of the Ordinary and its Application

to Aspects of Food and Feeding (2012) Physiol Behav 107: 606-613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.04.009 19.

Dubes R and Jain AK. Clustering Methodologies in Exploratory

Data Analysis (1980) Adv Comp 19: 113-238. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-2458(08)60034-0 20.

Wang

S, Lu J, Gu X, Du H and Yang J. Semi-Supervised Linear Discriminant Analysis for

Dimension Reduction and Classification (2016) Pattern Recognition 57: 179-189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.patcog.2016.02.019 21.

General Data Protection

Regulation. Howard

Moskowitz, Mind Genomics Associates, Inc., White Plains, 11 sherman ave, New

York, USA, E-mail: mjihrm@gmail.com General marketing, Computer technology and Personal

viewpoint identifierImbuing the Supply Chain with the Customers Mind: Todays Reality, Tomorrows Opportunity

Abstract

Full-Text

Introduction

Design

Thinking-Precursor Steps to Knowing the Mind of the Specific Customer

A

Re-Conception of a Moment of Truth-Communicating to the Mind of the Customer

The

Role of NO

Mind

Genomics Thinking: Uncovering mind-sets, i.e., basic patterns of acceptance

Demonstrating

the Mind Genomics Science by Sequencing Patterns of Individual Preferences

Table

2: The four questions and the nine answers to each question,

the brand names are part of the initial data acquisition (Mind Genomics) but discarded

for the PVI (personal viewpoint identifier).

Step 4-Transform the

ratings and create individual-level regression models: The analysis relates

the presence/absence of the 36 elements to the 9-point rating scale of interest

in the product as described by the vignette. In deference to the consumer-research

heritage of Mind Genomics, the ratings on a 9-point scale are converted to a binary

scale, with ratings of 1-6 converted to 0 and ratings of 7-9 converted to 100. For

each respondent the OLS (Ordinary Least-Squares) regression program computes a simple

model: Binary 0/100=k0 + k1(A1) + k2(A2) … k36(D9)

Each respondent generates a set of coefficients, k0 and k-k36.

The additive constant, k0, shows the likelihood of a respondent assigning

a rating of 100 to a vignette or combination lacking ny elements. The additive constant

is strictly a theoretical, computed measure because by design all vignettes comprised

2-4 elements. The additive constant is useful a baseline of interest, however, each

of the 36 elements generates a coefficient, either positive or negative. The size

of the coefficient tells us the incremental percent (positive coefficient) or decrement

percent (negative coefficient) that would be added to the additive constant. The

sum tells us the likely percent of responses of magnitude 7-9 for a specified composition

of the vignette.

Table

3: The coefficients for the relevant elements for each

Drink It! Study, with the source of the coefficients being the three mind-sets extracted

separately for each study. The brand names are not part of the input data for the

subsequent PVI, and are not shown. Discussion-Mind

Genomics +PVI to Create Opportunities for a New Type of Integrative Research

Conclusions

Acknowledgements

How

Mind Genomics and the PVI began

References

*Corresponding author

Citation

Keywords