Research Article :

Introduction Considering its implementation, the

linguistic and cultural diversity of Mindanao, however, brings much complexity

to the issue of language policy in education. With Mindanaos more than 26

provinces and over 25 million population (Philippine Statistics Authority,

2005), the government offers a challenging environment for implementing a

language policy that is suppose to serve all Mindanao regions and the rest of

the country. This language policy is part of a

rising trend around the world to support mother tongue

instruction in the early years of a childs education. In Southeast Asia, this

is apparent in a growing number of educational programs that use the mother

tongue approach. Good examples can be found in Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia,

Thailand, Timor LEste and Vietnam (UNESCO, 2007). With all this, the program is

now on its third year as it was implemented in 2011. Looking at this, the shift

towards mother tongue-based multilingual education is not a walk in a highway.

Numerous challenges need to be addressed like the production of materials,

training of teachers, management of resources, and perhaps, the socio-cultural

support to enhance this project. Concentrating on the MTB-MLE program

challenges, this study is hoping to underwrite something of relevant

contribution to the success of the MTB-MLE in Iligan City. Objective

of the study This study envisioned to examine the

challenges affecting the implementation of the MTB-MLE. Views coming from the teachers,

parents and students

from two school will be thoroughly examined. To come up with a very distinctive

output, two elementary schools were chosen as respondents: The Queen of Angels

School of Iligan (QASI) in Acmac, Iligan City and the Northeast-IA elementary

school in Sta. Filomina, Iligan City. The author believed that the two schools

can provide relative results on the challenges affecting the MTB-MLE in the

current setting. Hence, the following queries are hoped to be addressed

accordingly: 1. What is the general assessment of

the teachers, parents and students about the MTB-MLE? 2. What is the attitude of the

teachers, parents, and students towards the MTB-MLE? Do they support the

program? 3. What trials or challenges arise

relative to the implementation of MTBMLE? Significance

of the study This research addressed the current

and controversial topic in the Philippines which is very relevant in a

multilingual communities like Iligan City which is struggling to define its

educational language policy. Much of the current research on MTB-MLE is

situated in other contexts in which community members have been involved in the

initiative throughout planning and implementation stages. This study only

focuses on the challenges in which way will try to examine the policy and how

it is understood and supported by the stakeholders. It will contribute to the

literature by furthering the construction of local conceptualizations of

language policy outcomes within a larger national policy mandate. Further, the current study addressed

some theories by directing the focus of the analysis to the different policy

perspectives among the teachers, parents and students amidst the current policy

affecting the implementation of the MTB-MLE program. Language policy theory

suggests that language management occurs when external forces make decisions

for those at the ground level (Spolsky, 2011), but there is a need to

understand how language management might occur from the grassroots. While a

growing number of scholars have recognized the importance of involving local

stakeholders in the language policy process (Ricento & Hornberger, 1996),

relatively few studies have examined language policy from the perspective of

those in the community. Analyses of explicit policy statements do not yield

accurate representations on how policy is being carried out from the local

community stakeholders. A number of previous studies have

included only teachers assessment towards language or particular language

policies (Iyamu & Ogiegbaen, 2007). These are important in understanding

local stakeholders perspective of any reform and can help guide policy and

other development leading towards the success of the program. Even more

significant is the growing number of studies that have focused on teachers involvement

in language

policy implementation (Menken & García, 2010). This moves beyond the

mentality of policy as something that is done to people but points to the power

of those at the ground level to make change and become more appealing to all

concerned. Ironically, many of these studies have focused on teachers

resistance to language policies that prohibit using local languages in the classroom

in favor of national if not English language. The current study, however, will

differ because it will consider the ways in which teachers, parents and

students acted in the midst of a policy that supported the use of the mother

tongue. In addition, it will also examine the respondents active roles in the

MTB-MLE program, which is something currently missing in most of the literature

and studies (Ambatchew, 2010). Further, in terms of practical

significance, this research will address current and controversial topic for a

multilingual and multicultural community like Iligan which is struggling to

define its educational language policy. Since our country is the only place in

Southeast Asia to require mother tongue instruction in elementary school, little

is known about the implications of this national decision on a community level.

While hundreds of pilot programs for mother tongue education have been

implemented throughout the region, it is uncertain how they usher effectively

the programs policy to the local environment. Greater understanding on the

perspectives and actions of community members amidst this reform can provide

guidance for the next steps in upholding the program. In particular, since this

study will be conducted while the MTB-MLE program is on its full swing, there

is plenty of opportunity to learn from the stakeholders views and experiences

to shade light for future decision making regarding the MTB-MLE program in

Mindanao especially in Iligan. Glossary

of terms used Bilingual-(Individual or societal) ability to speak two (or more)

languages, or a model of schooling that uses two (or more) languages. Biliterate-Ability to speak, read and write two (or more) languages. Empowerment–Specific efforts to give learners the knowledge, strategies

and self-confidence to act to improve their own situations and those of others. L1-First

language or often interchangeable referred to as mother tongue. L2-Non-native language, second language, foreign language; may

specifically refer to contexts where the language is widely spoken outside the

home, but often used to refer official contexts. Lingua franca-Widely spoken language used for communication between

linguistic groups Maintenance-Continued development of a language through schooling. Medium of instruction-The language used in teaching and learning curricular

content. Mother tongue-First language (L1), native language. Multilingual-(Individual or societal) ability to speak more than two

languages. Transfer-Cummins concept that what is learned in the L1 contributes

to ones competence in other languages Transition Shift in the medium of

instruction from L1 to L2. Transitional-Schooling that shifts sooner or later from the L1 to the

L2. Theoretical

Framework The present study is anchored on

UNESCOs (2007) factors in the success of mother tongue-based multilingual

education program implementation, Bensons (2004), Danbolts (2011) and Malones

(2012) inventory of challenges in mother tongue-based multilingual

education. UNESCO (2007) emphasized that the

effectiveness of mother tongue-based multilingual education necessitates

thorough planning and commitment. The planners need to take into consideration

measures to ensure that the program is effective. These factors are language

model, teacher recruitment and preparation, materials development and

production, parental support, and education sector alignment. These factors guided the researcher

in framing the instrument for the study. They were considered and were modified

by the researcher to fit the present study. The researcher came up with

teachers MTB-MLE knowledge/assessment, instructional materials, and attitude

towards the program as the three main aspects to be considered in investigating

the challenges that stakeholders faced in the implementation of the mother

tongue-based multilingual education in Iligan City. Some authorities outlined challenges

in the implementation of the mother tongue-based multilingual education. This

list of challenges was also taken into account by the researcher. Benson (2004) mentions that one

challenge that may be faced in mother tongue based schooling is human resource

development. This means that human resource development is on the teachers

training. These trainings should not be carried out without appropriate

in-service and pre-service training. Along with this challenge is the

difficulty to find teachers who are competent in the L2. In consequence,

unqualified teachers with less training are hired especially when nationwide

implementation is done. Another challenge according to

Benson is on linguistic and materials development. She says that special

attention should be given to time and resources in the implementation of mother

tongue- education. Educators and people in the community should have time to

work together with linguists to be able to produce materials in the L1. Benson

stressed that there are problems in the implementation sometimes because people

who are involved in the implementation fail to reach a consensus on the

allocation of resources. Moreover, Danbolt (2011) cited

another challenge and that is on the attitude towards the language which is very

important in learning to use one or two languages. Learning a language goes

with attitudes of its users and of persons who do not know the language. When

one has a positive consideration towards the language being used, a feeling of

belongingness and identity exists. Skutnabb-Kangas and McCarty (2006) supports

this idea by saying that positive attitude towards language is in relation to

the feeling of being at home with the language. Benson (2004) posed that the

use of the mother tongue in the classroom makes students feel good about school

and their teacher. This happens because they are becoming knowledgeable in a

language familiar to them. This makes them be encouraged to demonstrate what

they know and participate in their own learning and eventually express

themselves. Malone (2012) as cited by Kadel

(2010) mentioned seven challenges in planning, implementing and sustaining an

excellent mother tongue-based education. These are multiple languages with

multiple dialects, absence of concrete orthographies, shortage of mother tongue

speakers with teaching materials, scarcity of written literature, various

mother tongues, large class sizes, and deficiency of curriculum and

instructional materials. Kadel also pointed out that challenges may also be

faced on poor coordination among government agencies, misconception and

differences in the knowledge about mother tongue-based multi-lingual education,

confusion of parents about the notion of mother tongue-based multilingual

education, qualms among teachers in the government schools due to the

apprehension of losing their jobs, eagerness of parents to send their children

to go to schools with English as medium of instruction, making MTB-MLE

inclusive for all since it aims for the utilization of non-dominant languages

speaking children only, and the unfair allocation of financial resources from

the agencies. Review

of Related Literature and Studies This part of the paper will present

the related literature and studies emphasizing the theoretical bases of the

present investigation. It incorporates theories relevant to the Mother Tongue

Based-Multilingual Education and its challenges. First, Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education. The United Nations Universal Declaration on

Human Rights (1948) affirmed the right to education without discrimination.

Article 2 of this document significantly addressed discrimination on the

grounds of language. Five years later, a well-cited UNESCO (1953) report

expanded upon this by suggesting that education in the mother tongue serves

multiple purposes: It is axiomatic that the best medium

for teaching a child is his mother tongue. Psychologically, it is the system of

meaningful signs that in his mind works automatically for expression and

understanding. Sociologically, it is a means of identification among the

members of the community to which he belongs. Educationally, he learns more

quickly through it than through an unfamiliar linguistic medium. (UNESCO, 1953) In the 1999 UNICEF statement

similarly acknowledged the value of mother tongue instruction: There are ample

researches showing that students are quicker to learn to read and acquire other

academic skills when first taught in their mother tongue. They also learn a

second language more quickly than those initially taught to read in an

unfamiliar language (UNICEF, 1999). Ten years later UNESCO (2003)

reiterated these points and stated that essentially all researches since 1953

have confirmed the value of education in the mother tongue. Other evidences from research

studies in the Philippines and elsewhere played a role in convincing policy

makers of the potential benefits of mother tongue instruction for language

minority students. Cited in the study conducted by Burton (2013), the benefits

highlighted from these studies include improved academic skills; stronger

classroom participation (Benson, 2004); increased access to education ; and

development of critical thinking skills. Research has also noted the effect of

multilingual education on cultural pride increased parent participation

(Cummins, 2000); and increased achievement of girls (Benson, 2004). Another

major benefit of mother tongue instruction is the foundation it builds for

gaining literacy in additional languages (Cummins, 2000). Two hypotheses relate

to this desired outcome: the threshold level hypothesis and the interdependence

hypothesis. Skutnabb-Kangas (2006) proposed the threshold level hypothesis

which suggests that only when children have attained a threshold of competence

in their first language can they successfully gain competence in a second

language. This hypothesis was formed as a result of research with Finnish

children who had migrated to Sweden. It was found that children who migrated

before they had gained literacy in their first language did not develop second

language literacy as successfully as those who migrated after they developed

first language literacy. Based on these, Cummins (2000)

consequently devised the widely cited interdependency hypothesis which asserts

that the level of second language (L2) proficiency acquired by a child is a

function of the childs level of proficiency in the first language (L1) at the

point when intensive second language (L2) instruction begins. He distinguished

between two kinds of literacy: interpersonal communication and cognitive academic

language proficiency (CALP). Interpersonal communication refers to oral

communication skills use in conversational settings, while CALP signifies the

point at which the speaker can use language in decontextualized ways, such as

through writing where language is a cognitive tool. Cummins concluded that L1

competency would be more easily transferred to L2 competency when CALP is fully

learnt. The relationship between the L1 and

L2 or L3 is particularly relevant in the Philippines because of the economic

opportunities associated with English proficiency. As generally perceived,

English would facilitate faster mobility—a kind of idea that Hall (1997)

positively posters. In 2009, over 11% of the population worked overseas to

provide 13.5% of the national GDP in foreign remittances (Bangko Sentral

Pilipinas, 2010) and domestically-based call centers for foreign companies

supplied about 4.5% of the national GDP in 2009 (USED, 2010). As a result of

the strong national and individual economic benefits of English proficiency,

there is a strong desire in the country to improve the English literacy skills.

Most researches on literacy outcomes

related to mother tongue instruction were done in North America and Europe. In

spite of this Western focus on language learning studies, it has served for

much of the rationale in propagating usage of the mother tongue in education

throughout the rest of the world. Researchers like Ramirez (1991), Thomas and

Colliers (1997) major longitudinal studies in the United States found that

language minority children who were educated in their home language for a

majority of their elementary school years demonstrated stronger gains in

English proficiency than other language minority children who were educated

only in English or for just a short time in their first language. The finding

is being reinforced by other research that has suggested strong first language

abilities will advance cognitive development in children and allows them to

easily negotiate in other subject matter (Mallozzi and Malloy, 2007). Other

studies also indicated that English (or other second language for this matter)

literacy skills develop more easily and efficiently when they are based in a

childs understanding of their first language (Cummins, 2000). Other researches outside of the

Western context have produced similar outcomes. One of the most well-known

MTB-MLE initiatives took place between 1970 to1978 in Nigeria. The result

showed that students who learned in their first language for six years

demonstrated higher overall academic achievement than students who only learned

in their first language for three years. The first group showed no difference

in English proficiency from the second group despite having had fewer years

with English as the medium of instruction (Fafunwa, Macauley, & Sokoya,

1989). In our country, the Philippines, a

longitudinal study was conducted with the grade one to three students in

Lubuagan, a rural community in the Cordillera Mountains. The mother tongue

pilot project began in one school in 1999, and the study was formally launched

in 2005 with three schools in the experimental group and three in the control

group. After three years of the study, consistent advantages were noted for the

children in the mother tongue schools. They scored significantly higher than

students in the control schools in math, reading, Filipino, and English (Walter

& Dekker, 2011). Field researcher, Akinnaso in 1993

reviewed literature on mother tongue based programs in developing countries and

claimed that most projects yield positive correlations between the development

of literacy in the mother tongue and development of literacy in the second

language. However, the use of the mother tongue alone does not guarantee an

overall positive result. Consideration must be given to the ways in which the

policy is implemented, both from a national and local standpoint. Scholars from anthropological

traditions have argued that top-down language

policy issues give more weight to expert knowledge than local knowledge

(Canagarajah, 2005). While the quantitative evidence found in the

aforementioned studies validates the use of MTB-MLE, it does not account for

local understandings of language learning. Context shapes the way in which

policy can be implemented, and those at the ground level create their own

knowledge about effective and ineffective strategies even if they are not

recognized in scholarly literature (Canagarajah, 1993). While local knowledge

should be considered, Canagarajah (2005) warns about the possible consequences

of regarding it exclusively. He pointed out that celebrating local knowledge

should not lead to ghettoizing minority communities, or forcing them into an

ostrich-like intellectual existence. The bridge between these two types of

knowledge must be created for a good understanding to transpire. The success of multilingual language

policies at national and local levels is dependent upon the presence of

ideological and implementational spaces. Hornberger (2002) introduced these

terms in her seminal work on the continua of biliteracy to explain how local

stakeholders could take advantage of openings in language policy to promote

multilingual education. She suggested that ideological spaces are opened up

when societal and policy discourses begin to accept and value non-dominant

languages for education. In our country, the policy has created an opening for

this ideology, but it is unclear if the societal discourse will follow. On the

other hand, implementational spaces are created when content and media for

instruction utilize local, contextualized viewpoints rather than the majority,

decontextualized perspectives traditionally observed in educational systems. As observed, while the concepts can

be described separately, they are interrelated in practice. As Hornberger

(2002) stated, it would appear that the implementational space for popular

participation is of little avail in advancing a multilingual language policy if

it is not accompanied by popular participation in the ideological space as

well. Apparently, it appears to influence the other in a way that each is a

necessary component of multilingual education

initiatives. Ideological and implementational domains of language reform

deserve attention when studying the way in which a national policy is

understood and enacted at the local level. Second, Spolskys language policy.

Spolsky (2011) proposed a theory of language policy. He argued that the goal of

a theory of language policy is to account for the choices made by individual

speakers on the basis of rule-governed patterns recognized by the speech

community (or communities) of which they are members. His theory is encompassed

by three assumptions which must be tested and adapted. The first assumption is

that language policy is a social phenomenon constructed in a variety of

domains, including homes and schools. A second assumption, as presented in his

book Language Policy (2004), assumes the presence of three separate but

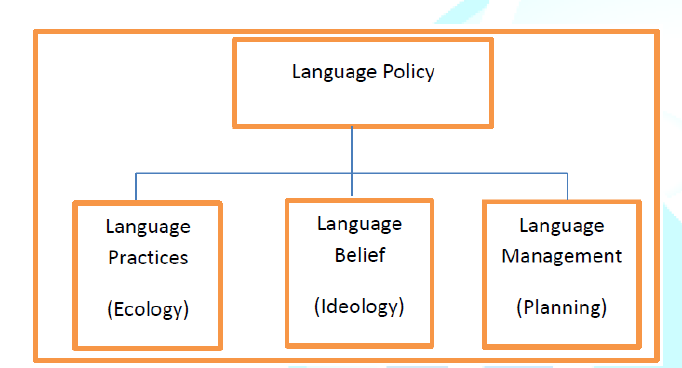

interrelated components: beliefs, practices, and management (see Figure 1.) The

third assumption focuses on the influence of internal and external forces on

language choice. Spolsky (2011) suggested that these may come from within or

outside of the domain and may be language-related or not. The three components of language

policy deserve closer attention. Language Practices, refer to the language

selections that people actually make. This is often described in terms of the

sound, word, and grammatical choices made within a community including

the societal rules about when and where different varieties of language should

be used. These practices are shaped by the complex ecology of language or the

interactions between language and the social environment (Spolsky, 2004). They

may include decisions made by individuals to use a particular language in one

setting but not another. The language belief, on the other

hand, sometimes referred to as ideology, explain the values held by members of

a speech community toward language and language use. Spolsky (2004) described

it as what people think should be done. While many beliefs may be present

within a community, there is commonly one dominant ideology that favors a

particular language approach. The Language Management is defined

as any efforts made to influence language practices. Sometimes referred to as

language planning, this component emphasizes the direct intervention aimed at

shaping the way in which a policy is enacted. While Spolsky (2004) pointed out

that language managers can include any person or entity that attempts to affect

the language choices of other people, management is most commonly associated

with individuals or documents possessing legal authority. An example could

include written legislation in support of a particular language policy. Indeed,

so political in nature. And Third, Ricento and Hornbergers language policy and

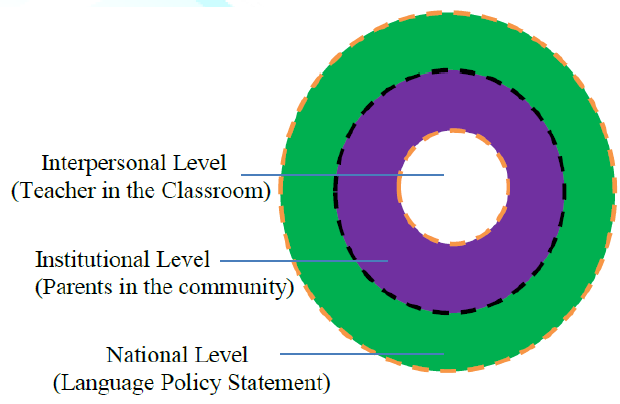

planning model. Ricento and Hornbergers (1996) language planning and policy

(LPP) model complements and enhances Spolskys theory by considering actors

within each of the national, institutional, and interpersonal levels. In this

ground, the national level refers to the language policy statements; the

institutional level refers to parents as actors in the community; and the

interpersonal level refers to teachers as players inside the classroom. An

examination of each level of Ricento and Hornbergers (1996) model highlights

how reform implementation approaches from the national or community level

interact to influence implementation at the classroom level. Ricento and Hornbergers (1996) model

is depicted as the layers of an onion that together make up the Language Policy

(LP) whole and that affect and interact with each other to varying degrees.

Each layer infuses and is infused by the others. The figure below, figure 2,

illustrates this model by depicting the agents, levels, and processes involved

in language planning and policy. Agents from all three levels (national,

institutional, interpersonal) interpret the language policy goals and

objectives, and then negotiate between and within levels about the policy

implementation process. The LP model considers language planning and policy

implementation as a multidirectional process that considers downward and upward

priorities. This is depicted by dotted lines and concentric circles, which

demonstrate movement and interactions between the national, institutional, and

interpersonal levels of the model in language policy interpretation. This

process can create conflict and ambiguity in policy goals and objectives, resulting

in misalignment between layers (Ricento & Hornberger, 1996). Figure 2: Ricento and Hornbergers (1996) model. The multidirectional nature of

language interpretation and implementation is a necessary, but conflict-laden

process. It suggests that language policy is not simply defined by national

level implementers. Rather, the onion model depicts the complexity at play in

shaping decisions made at a local level. Teachers are specifically noted for

their role in reform implementation. In the study of García and Menken (2010)

they pointed point out: It is the educators who cook and

stir. The ingredients might be given at times, and even a recipe might be

provided, but all good cooks know, it is the educators themselves who make

policies--each distinct and according to the conditions in which they are cooked,

and thus always evolving in the process. While the role of educators in the

interpersonal level of this model is given much attention in theory and

practice, less attention has been given to the alignment and interactions

between teachers and parents within the same community. Thus, this study will

utilize the classroom, community, and national policy levels in Ricento and

Hornbergers (1996) LPP model as a lens from which to view Spolskys (2004, 2011)

three components of beliefs, practices, and management. Research Methodology and Design The researcher adopted the

Qualitative Participatory Method by Davies and Dart (2005). Such approach is

deemed appropriate for the current study. The method was administered by making

use of a direct classroom observation, questionnaire, and interview. The

questionnaire is necessary for it serves as springboard in the latter interview

with the respondents. Data were collected in July, August and September 2014 in

two schools in Iligan City (QASI and Northeast 1A). The qualitative component

consists of random interviews with the grades 1 to 3 teachers, parents, and

students. The researcher randomly selected 10 teachers, 10 parents, and 10

students per school; with the total of sixty (60) respondents all in all. The

interview questions focused on the knowledge/assessment, attitude, challenges

and other concerns that they have encountered which may affect the MTB-MLE

implementation. The quantitative component includes a questionnaire in which

the grades 1 to 3 respondents responded to items related to their knowledge,

instructional materials, attitude, and challenges about MTB-MLE in general. In

addition, classroom observations were also conducted. Observations included the

classroom environment as well as teaching practices and student responses. Locale

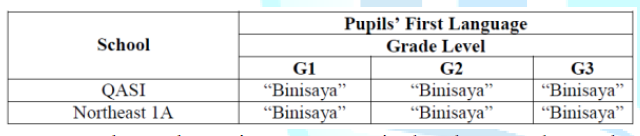

of the study The study was conducted in two

elementary schools, the Queen of Angels School of Iligan (QASI) in Acamac,

Iligan City and the Northeast 1A Central Elementary School in Sta. Filomena,

Iligan City. The respondents speak Binisaya and a handful few can speak Maranao

and Tagalog. These two schools are offering complete elementary education and

in these schools the grades 1 to 3 students with their parents and teachers

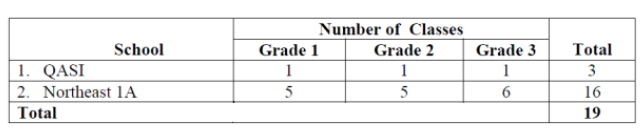

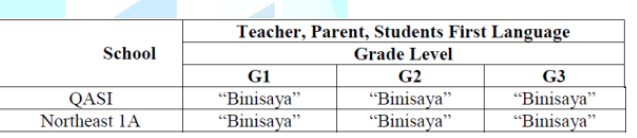

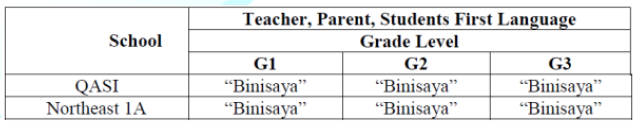

were used as respondents of the study. Table 1: The Students First Languages in the Three Grade Levels. Table 2 reveals the number of grade

1, 2, and 3 classes in the two schools. The QASI has 1 section per grade level

for grades 1, 2, and 3. On the other hand, there are a total of five grade 1

classes, five grade 2 classes and six grade 3 classes in Northeast 1A with a total

of sixteen sections all in all. Obviously, it can be seen in the table that

Northeast 1A has a bigger population compared to QASI. For equal treatment of

respondents, however, the researcher decided to use only ten (10) per group of

respondent – that is 10 parents, 10 teachers, and 10 students per school with

the total of sixty (60) respondents all in all. Table 2: Number of Grades 1, 2 and 3 Classes in the two Schools. Research

Participants The participants of the study were

the grades 1, 2, and 3 students, teachers and parents from two elementary

schools (Private and Public) in Acmac and Sta. Filomena, Iligan City. Table 2

shows the distribution of grades 1, 2, and 3 classes in the two schools. Of the

nineteen classrooms, only 10 parents, 10 teachers, and 10 students per school

were being randomly selected as respondents. Hence, it will give the total of

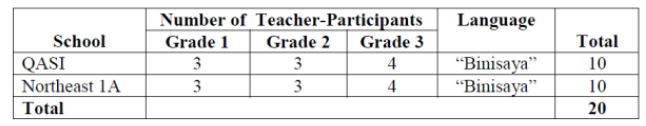

60 respondents from both schools. Table 3: The Distribution of Teacher-Participants in the two Schools. The twenty teachers in both schools

used Binisaya as their first language. Table 3 also reflects the number of

respondents per year level and the teacherparticipants first language. Three

(3) teachers are from grade 1, three (3) from grade 2, and another four (4)

from grade 3. Each school has equal respondents per year level with the total

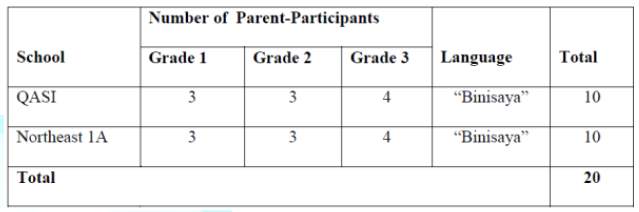

of twenty (20) teacher-participants all in all. Table 4: The Distribution of Parent-Participants in the two Schools. The twenty parents in both schools

used Binisaya as their first language. Table 4 reflects the number of

parent-participants and their first language. Table 5: The Distribution of Students-Participants in the two Schools. The twenty students in both schools

used Binisaya as their first language. Table 5 reflects the number of

student-participants and their first language. It can be gleaned from the set

of tables above that both schools are equally represented starting from the

teachers up to the parents and pupils. Table 6: Teachers, Parents, and Students First Languages in Grades 1, 2 and 3. The table reflects that the 60

respondents have Binisaya as their first language. Sampling

Procedure Used A random sampling was used in the

study. The researcher had chosen only two elementary schools because of the

following pragmatic reasons: a) accessibility; b) financial consideration; and

c) time affecting the data gathering. Instrument

Used The researcher adopted and modified

Amor Claridos (2013) questionnaire which was constructed based on UNESCOs

(2007) factors in successful implementation of mother tongue-based multilingual

education and on the challenges outlined by Malone (2012). The questionnaire was

validated by an expert. Revisions were done to adopt the experts suggestions

and the final questionnaire was produced. The questionnaire has three parts.

The first part is on the profile of the participants (see appendix A). The

second part is a checklist with items related to the MTB-MLE information and

the third is on the challenges. The last part allowed the respondents to rank

the other challenges that they might have encountered in regards to the MTB-MLE

implementation. Data

Gathering Procedure The researcher followed the

resourceful steps in gathering the data for the study. This made the whole

conduct of the research tedious and exhausting. A letter asking permission was sent

to the school principals in the two chosen schools (see appendix C). The researcher

scheduled a five-day visit per school. He first visited the QASI then the North

East 1A there after. The scheduling was based on the availability of the

respondents per school. The signed and duly approved letter of permission was

handed to the teachers per year level as well as the parents. The

questionnaires were then administered and were retrieved immediately after the

respondents answered them. The Interviews were conducted after

the observation and retrieval of the questionnaires. The researcher looked into

the reading materials used by the grades 1, 2, and 3 teachers in both schools.

Since almost the same materials were available in the two schools, the

researcher considered the materials in the second school. He also tried to look

into the different materials used by teachers in the both schools and tried to

document the observations. Looking into the materials, some probing questions

were thrown by the researcher to gather information that may help the

researcher in understanding the challenges the teachers may have faced. The

classroom observations were done to gather data on how children responded to

mother tongue teaching and how teachers delivered

their lessons in the mother tongue. The data gathered from the questionnaire

helped the researcher understand peculiarities in the classroom. Finally,

probing questions with the respondents were also conducted to clarify some

responses in the checklist, to verify their comments reflected in the last part

of the questionnaire, to ask about some clarifications on the materials used,

and to elaborate some events that had happened during the classroom

observations. Data

Analysis The data on the challenges met by

the respondents in two schools were analyzed based on Besons (2004) and

Danbolts (2011) challenges in MTB MLE. Statistical

Treatment After the data were gathered the

researcher used frequency and percentage to come up with the results. Results

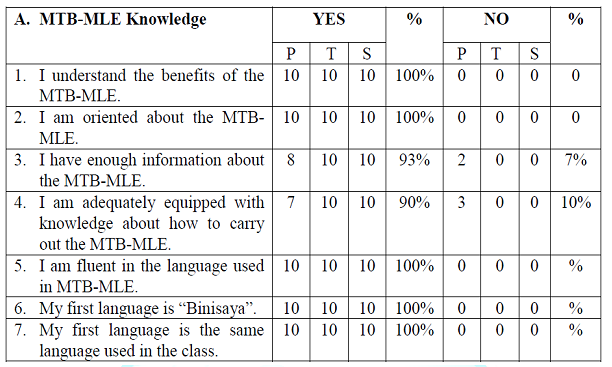

and Discussion Table 7 and 8 present the challenges

faced by the respondents in regards to the implementation of the mother

tongue-based multilingual education. The table reveals the respondents

knowledge/assessment in MTB-MLE. From the private school, it can be seen that

items 1 to 7 which talk about their MTB-MLE knowledge, of the 30 respondent,

they indicated that they are knowledgeable about the program. A negligible

percentage covering items 3 and 4 (on MTB information and knowledge on how to

carry out the MTB-MLE) that would count to 7% and 10% only. This indicates,

though so little, that the parent-participants considered these two items as

challenges in teaching the MT Binisaya to their children. Two parents do not

have enough information and that they are not adequately equipped with

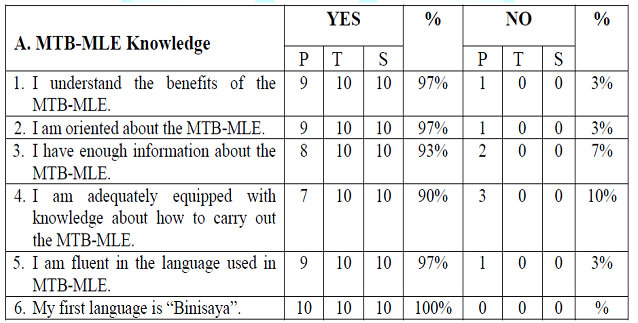

knowledge about the MTB-MLE. As for the public school, parents are very

skeptical in regards to their responses. As reflected in the table, though

majority of them know about the MTBMLE program, but a handful few claimed that

they are not totally knowledgeable about it. This does not, however, affect the

whole sentiment of the 30 respondents especially the teachers and pupils coming

from the public school. The responses in tables 7 and 8 vary

when it comes to MTB-MLE Knowledge. The parents in particular were not all

knowledgeable about the program. Items 3 and 4 give 7% to 10% variance compared

to the parents in private school. This result implies that not all parents are

updated about the program. Teachers and students, on the other hand, are saying

that they are knowledgeable. This finding agrees with UNESCOs (2007) as cited

in the study of Ball (2011). With mother tongue used in the classroom, UNESCO

(2007) pointed out that the use of the MT in the classroom would make the

pupils express what they want to convey. This happens because pupils are able

to understand what is discussed in the class and they are able to speak because

they use their own language. This case is true in the present study. Further,

the same finding is revealed in the study of Chihana and Banda (2011). Table 7: Participants Responses for the MTB-MLE Knowledge (Private). Table 8: Participants Responses for the MTB-MLE Knowledge (Public). The most obvious implication here is

the displacement of English and Filipino as media of instruction. This is one

reason why DepEd Order No. 74 is believed to have both supplanted the official

bilingual education policy of the country which has been in place for almost

three decades now, and ushered in the possibility of a multilingual education

in the Philippines. Whether MTB-MLE succeeds in the end still remains to be

seen because of the many challenges it must hurdle (Nolasco), education in the

Philippines.Whether MTB-MLE succeeds in the end still remains to be seen

because of the many challenges it must hurdle (Nolasco), but one factor that

needs to be recognized is that MTB-MLE claims to be additive (as opposed to

subtractive) in its approach to multilingual education. While teachers and parents differed

in their knowledge of the MTB-MLE policy, their awareness of the guidelines

similarly came from the national level. Those from QASI, considering their

frequent visit in the school, it can be deduced that their queries about the

MTB-MLE would somehow addressed by the teachers or even the principal they see

every now and then. Parents from Northeast 1A, however, received even less

information about the program as it was relayed to them only through their

brief meetings with teachers. In some cases, they had not completely understood

it all. This demonstrated a weakened diffusion of knowledge (Wedell, 2005) in

which information filtered down through a series of different sources of

information. While teachers and parents in this study were aware of the

logistical aspects of the policy related to their specific roles, they had less

understanding about the more nuanced aspects of the policy, including the

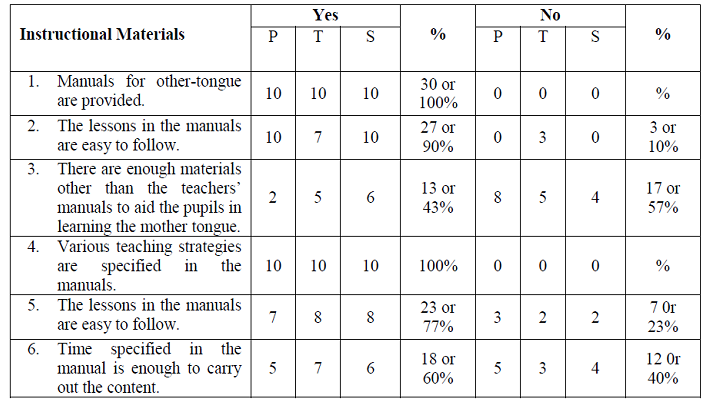

rationale for the MT implementation. Tables 9A and 9B present the

challenges the participants faced in the implementation of mother tongue-based

teaching in terms of instructional materials. Table 9A: Participants Response on the Instructional Materials (Private). Table 9B: Participants Response on the Category Instructional Materials (Public). Table 9A shows that the item The

lessons in the manuals are easy to follow 3 teachers answered no while

the item There are enough materials other than the teachers manuals to

aid the pupils in learning the mother tongue 8 of the parents answered no, 5

from the teachers, and 4 from the students. For item the lessons in the manuals

are easy to follow, 3 of the parents answered no, 2 from the teachers and 2

from the students also answered no. For the item Time specified in the manual

is enough to carry out the content, 5 parents, 3 teachers and 4 students

answered no. These notable responses would manifest that MT instructional

materials remain inadequate in their school thereby affecting academic

instruction and pupils academic performance. It further implies that teachers

might resort to hunting for Mother Tongue (MT) references even though they are

not sure of the material suitability or effectiveness when used in the class. In the interview, it was mentioned

by Teacher Jenilyn that they learned that they would be implementing the MT

only one week prior to the start of the school year. They did not receive MT

materials right away; rather during the second week of school they were

provided with curriculum guides that listed core competencies. Later, school

heads provided them with teachers guide that included some lessons and student

worksheets, but these materials had to be reproduced at the cost of the

teachers. Teachers claimed that their teaching had suffered because of the

limited materials. According to her: This kind of statement was commonly

heard among her fellow teachers. Another teacher explained that they are

grappling in the dark to navigate their way through this shift without

resources. Materials provide guidance for teachers, and they all expressed this

during their meetings. She said, DepEd says grade one teachers are the champion

of change, but how can we be the champions of change if we dont have enough

materials? Teachers confined their lament to the classroom and other school

contexts. Teachers compensate the challenges based on their own knowledge,

beliefs, and practices, but the national level did little to address them.

Fullan (2003) suggested: One of the basic reasons why planning fails is that

planners or decision makers of change are unaware of the situations faced by

potential implementers. They introduce changes without providing a means to

identify and confront the situational constraints and without attempting to

understand the values, ideas, and experiences of those who are essential for

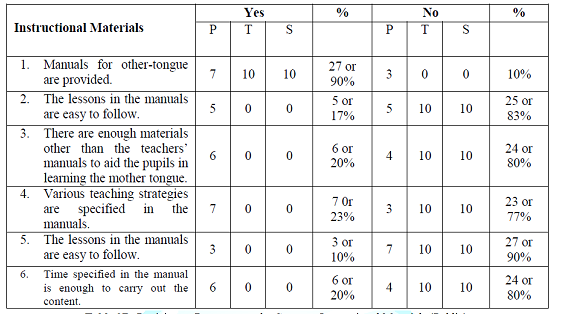

implementing any changes. Table 9B shows that item Manuals for

other-tongue are provided was lightly marked by 3 parents with no answers. The

remaining items were marked heavily with 100% no answers by all respondents

from Northeast 1A. They stood incongruent to what has been expected by the

researcher. This would imply that the school lacks or had limited MT materials

to carryout the teaching in the classroom. The researchers visit to the

classrooms made this challenge clearer. It was revealed that aside from one

copy of the teachers manual provided to each grade one and two teachers, only

one copy of the learners material was provided to each of them. This one copy

of the learners material is not enough for more than forty pupils in one class.

This gave the teachers problem since they had to draw on the board (if not on

the chart) the figures found in each page of the learners material to be able

to deliver it to the pupils. Teachers Joycelyn Alisbo and Rosanna Langilao

cited that their time spent on drawing the figure almost consumed the whole

period every time they conduct their classes. They had to do it anyway since

they lack resources in producing the materials. On the other hand, parents

described the lack of resources in a slightly different way. They hinted other

means of acquiring Binisaya books and resources

available to them for use at home and described the challenge of working with

their children without those resources as (lisod kaayo) very difficult. These

materials have not been adequately produced by the government, much less for

commercial purposes. This case is also true in the study of Clarido (2013) in

Bukidnon. The same case in Kenya in the study of Gachechae (2010) and in

Nigeria in the study of Iyamu (2005). In Kenya and Nigeria, the lack of

instructional materials in teaching the mother tongue hindered the teaching of

the content to the local languages. UNESCO (2004; 2007) stressed that materials

should be available for the delivery of the languages. Teachers in the study described

their coping mechanism as the development of collaborative relationships.

Despite the complex environment for addressing the challenge, the level of hope

remained high for both teachers and parents. Despite the complex environment

for addressing this challenge, the level of hope remained high for the teachers

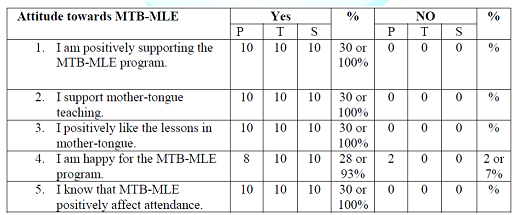

and parents. Table 10 (A and B) present the

challenges faced by the teacherparticipants in terms of attitude towards

language. Table 10A: Participants Response on the Attitude towards Language (Private). Table 10A presents a positive

response of the respondents from the private school. Only a 2 parents answered

no for the item I am happy for the MTB-MLE program. It is a negligible

percentage which would otherwise speak that majority of the respondents from

QASI is happy about the MTB-MLE program. While they could see that

MTincreased understanding in the first years of education, this benefit might

not appear to extend to higher grades. This may be the difference between

what teachers and parents have observed and what they have not yet observed

Guskey (2002). The MT immediate benefits were apparent, but it was more

difficult for them to foresee how this advantage could extend in the future

grades of their children. However, they expressed optimism during the

interview. Mrs. Saldaga confidently expressed it by saying (dali ra man;

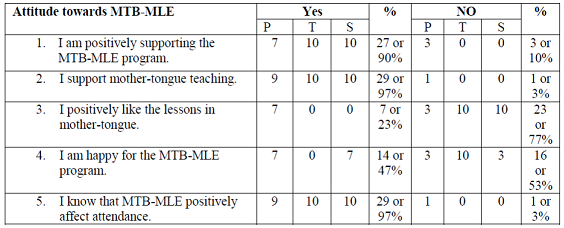

problema, wa lay libro) it is easy but the problem is they have no books. Table 10B: Participants Responses on the Category Attitude towards Language (Public). The Table 10B shows that only

teachers and students favored items 1, 2, and 5 which obtained 100% yes

responses. The rest of the items are directing to no answers. The ietms depict

a negative attitude among the parents, teachers, and students. Items 3 and 4

even indicate that the teaching of the mother tongue did not influence the

liking of MT lessons and they are not happy with the program. One parent

answered that it does not help improve pupils attendance. The majority,

however, think otherwise. The interviews with the teachers revealed that the

problem on poor attendance has long been experienced in the schools due to some

factors other than the MTB. This finding agree to what Benson (2009) cited.

Benson said that the use of the mother tongue makes pupils feel good about

school. This implies that when students have a positive feeling towards school,

it would mean that they would also have a positive feeling toward the teacher

and they would eventually come to school. In the case of the pupils, they may have

had a positive feeling toward their teachers but the language used in the

classroom might have not made them feel at home since it was not the language

that they understood better. English was still prevalent. Looking back in items

3 and 4, the teachers and students dont like the lessons in their books and

they are not happy about it. In the interview, it was revealed that their book

lessons were not consistent with the guide that they have in the MT teachers

manual and thereby making their class discussions more problematic. Teacher

Rosanna Langilao said: The teachers manual does not jibe with the textbook.

Another significant point which is worth mentioning is the comment of Teacher

Melba Montecino. She said: We need to provide dictionary for MTB-MLE. Big books

are needed for telling story and in Math discussion. She even pointed out that

she discusses in Binisaya but gave her exams in English. Its confusing.

Makalibog! she admitted. This observation is supported by Teacher Joycelyn

Alisbo: If only we got enough MT materials and books then we can conduct our

class successfully. Such ideas are also evident in the study of Danbolt (2011)

and Burton (2013). Overall, the MTB-MLE appears to

challenge the teachers abilities to implement it in the classroom. Three main

points were uncovered in the data affecting the attitudes of the respondents.

These include the environment of the community, the difficulty in translating

academic language Binisaya to English and vice versa, and the limited resources

and materials available to teachers and parents to support the efforts of the

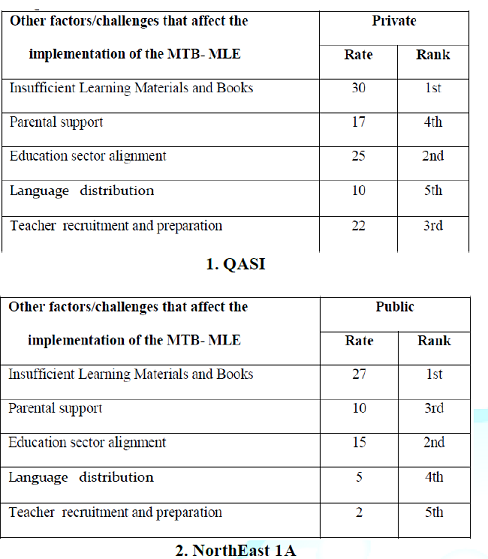

MT endeavor for the students. In the succeeding questions, the

researcher opted to use them for the parents and teachers only. Other than its

magnitude and depth, it is presumed that these questions would matter for the

parents and teachers only. The teachers and parents respondents were asked to

rank the other factors that may have affected the implementation of the

MTB-MLE. They were asked to identify which of the five challenges is considered

to be on top. Hence they were marking the choices between 1 to 5 and in which

ranking 1 is considered the highest and 5 is the lowest. D.

Other challenges/factors affecting the implementation of the MTB-MLE

(Teachers/Parents Only) Significant insights The interviews, questionnaires, and

observations yield consistent result. MT books and materials garnered the

highest position in terms of MTB-MLE challenges. Looking at it, although the

new MTB-MLE policy and its provisions are good as what advocates have been

fighting for, the rush in implementing the program seems risky and may result

into failure. If the program has to survive, the

researcher strongly suggests that the following challenges need to be addressed

accordingly: Materials development: Materials development would include, among others, books

for both teachers and students must be available in the Binisaya language being

ranked of the MTB- MLE by the two schools. Teacher recruitment and preparation: Availability of teachers who are speakers of the target

languages is also a key consideration for program development. Language distribution: Key questions regarding the distribution of languages

spoken in a community need to be answered in order to design an effective

program. Education sector alignment: To ensure the success of MTB education programs,

governments must structure all aspects of the education system to be aligned in

support of the chosen model. Parental support: Parents support is essential to the success of a mother

tongue education program. Therefore, parents need to be well informed about the

benefits of MTB instruction and reassured that learning in the mother tongue

will not hinder their childrens opportunity to learn a foreign or national

language, often a key goal of sending their children to school. Finally, while

Republic Act (RA) 10533 is in place, MTB-MLE challenges are growing. But such

challenges must not stop the MTs noble intention. Its birthing stage must not

be allowed to die, but must be cherished, nurtured, encouraged until it will be

perfected or so in its practical sense. Elucidating the concurrent challenges

is part in giving a solution. Hence, the researcher put forward the self-made

theory called the Ethno-lingo propagar theory. It means collectively

propagating a community-based learning materials and books to answer the

current educational needs of the community affected by the MTB-MLE program. Table 11: Factors affecting the implementation of the MTB-MLE. Conclusion The stakeholders from the Queen of

Angels School of Iligan and Northeast 1A are supportive of the Mother Tongue

Based-Multilingual Education but skeptical. They seem to believe that the

MTB-MLE is merely affecting the educational change in terms of policy written

in papers but not in practice. The MTB-MLE initiative is promising, but unless

tangible reforms and improvements in the quality of school facilities, teachers

trainings and learning materials, community and government support are

demonstrated, MTB-MLE will remain stuck in the quagmire of lapses as they

affect the program itself and the stakeholders at present. Challenges are

growing. Unless we resolve them, MTB-MLEs future remains vague. Recommendations Based on the findings, the

researcher recommends the following: 1. That DepEd officials, school

administrators, concerned communities and NGOs must find ways to provide the

schools with necessary MT learning materials, especially books, to ensure that

teachers will carryout their lessons successfully. 2. That DepEd should take into

consideration the in-service trainings for teachers. It must be intensified for

teachers handling grades 1, 2, and 3. 3. There is a need for a thorough

information dissemination and or reorientation for stakeholders especially the

parents. 4. Reclaim the childrens right to

learn in their own language through Ethno-lingo propagar theory. 5. Finally, a comparative and

experimental study between and among the private and public learning

institutions will also be conducted in order to measure the MT learning

outcomes quantitatively. References 1.

Acuña,

Miranda. A closer look at the language controversy (1994) In the language issue

in education. Manila and Quezon City: Congress of the Republic of the

Philippines. 2.

Advocacy

kit for promoting multilingual education: Inclusing the nexcluded (2007)

Community members booklet. 3.

Akinnaso.

Development debacle: The World Bank in the Philippines, California (1982)

Institute for Food and Development Policy. 4.

Almario

VS. Mother tongue-based multilingual education (2013). 5.

Ambatchew.

Traversing the linguistic quicksand in Ethiopia (2010) In: Negotiating language

policies in schools: Educators as policymakers, Menken K and García O (edtrs),

New York, Routledge, 6.

Ball

J. Enhancing learning of children from diverse language backgrounds:

Mother-tongue-based bilingual or multilingual education in the early years

(2011) UNESCO, France. 7.

Bangko

Sentral ng Pilipinas. Philippines Overseas Employment Administration (2009). 8.

Benson,

Danbolt. The importance of mother tongue-based schooling for educational

quality: Report Commissioned for EFA Global Monitoring Report 2005 (2011)

UNESCO. 9.

Benson

C. Do not leave your language alone: The importance of mother tongue based

schooling for educational quality (2004) Multilingual Philippines. 10.

Burton.

Mother tongue-based multilingual education in the philippines: Studying

top-down policy implementation from the bottom up (2013) University of

Minnesota, USA. 11.

Canagarajah,

Rajagopalan, Canieso-Doronila, Maria Luisa. The emergence of schools of the

people and the transformation of the philippine educational system (2005)

UP-CIDS Chronicle 3.1 63-97. 12.

Chihana

V, Banda D. The nature of challenges teachers face in using Malawi breakthrough

to literacy (MBTL) course to teach initial literacy to standard one learners in

Mzuzu, Malawi (2013). 13.

Clarido

A. Challenges in the implementation of mother tongue-based multilingual

e Mother Tongue, Multilingual Education

Mother Tongue Based Multilingual Education Challenges: A Case Study

Full-Text

To impart the lessons to the pupils, in my opinion, is easy. Its easy for them

to understand because they can comprehend easily. We could use them if they are

ready, we can execute the lesson clearly to the pupils. What is important are

the materials for us to execute the lessons

properly.

Keywords