Case Report :

Hannah Jethwa, Maaz Rana,

Jamie Kitt, Sarah Menzies, Alan Steuer and Simona

Gindea Systemic

Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease characterized by multi-organ

damage mediated by immune complexes and autoantibodies. It often presents with

patients being non-specifically unwell and there is a wide range of

differential diagnoses, one of which includes chronic infections such as Tuberculosis

(TB). Exudative pericarditis is a relatively common feature in SLE and is

present in up to 62% of patients on autopsy, although only a quarter of

patients are symptomatic; constrictive pericarditis is a very rare feature of

SLE. We report a 49 year old gentleman who was diagnosed with SLE which

presented with features of constrictive pericarditis following an extensive

period of investigations for TB. We

report a 49 year old man who, other than having an unprovoked pulmonary

embolism in 2012, is otherwise fit and well. He is originally from Gambia but

has been working as a chef in the United Kingdom for the past 25 years. He last

travelled to Gambia in 2014, where he spent two weeks. He does not drink

alcohol and has never smoked. He has a family history of sickle cell disease,

but nil else of note. He presented to hospital in December 2015 with a several

week history of malaise, lethargy and shortness of breath. This was associated

with a cough which was occasionally productive of clear sputum, and over this

period he had a reduced appetite and had lost half a stone in weight. On

examination he was cachectic and had bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy. He

reduced bi-basilar air entry on his chest and abdominal examination revealed

hepatomegaly. Cardiovascular examination was unremarkable, with no evidence of

a murmur or pericardial knock. He had no signs of clubbing or peripheral

oedema. No skin rashes were noted. Bedside observations were stable other than

tachycardia (112 Beats per Minute (bpm)); of note, blood pressure was normal. His

initial investigations showed chronic microcytic anaemia with a Mean

Corpuscular Volume (MCV) of 71 fl. He had raised inflammatory markers with C-Reactive

Protein (CRP) of 73mg/L and Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) of 15 mm/hr.

Sputum cultures including those for Acid-Fast Bacilli (AFB) were negative.

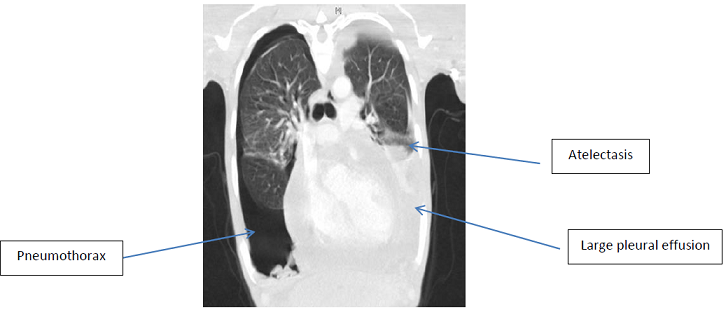

Chest X-ray demonstrated bilateral pleural effusions with bi-basal

consolidation. Further

investigation including a Computer Tomography (CT) of his chest revealed

enlarged axillary, cervical and supraclavicular lymph nodes as well as

pericardial and bilateral pleural effusions with a right sided pneumothorax. He

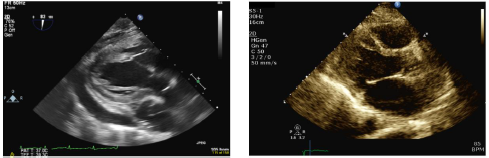

then went on to have an echocardiogram which showed moderate circumferential

pericardial effusion with fibrinous strands; his ejection fraction was 64%.

There were no echocardiographic features of tamponade at that point, although

he had septal bounce and Tissue Doppler Imaging (TDI) patterns across the

mitral and tricuspid inflows were consistent with a constrictive effusive

picture. Intravenous Cholangiogram (IVC) at this time was <2 cm and

collapsed ~ 50%, which represents normal filling pressures. The main differential diagnosis at this stage was pulmonary

tuberculosis complicated by pleural and pericardial effusions and a pneumothorax.

Upon review by the respiratory team, he was started on the full

anti-tuberculosis treatment as well as 60mg of prednisolone (equivalent to 30mg

due to Rifampicin interactions) for the pericardial involvement. His left

pleural effusion was drained for symptomatic relief. The pleural fluid was

exudative and lymphocytic with a protein of 55.3 g/L, LDH of 178 u/L and few

White Blood Cells (WBC), 95% of which were lymphocytes. The fluid glucose was

6.3 mmol/L. An incision biopsy of his left axillary lymph node was performed,

which revealed reactive lymphadenitis. pleural fluid, serial sputum and lymph

node fluid cultures were, however, negative for TB (Figure 1). He

was discharged from hospital when his symptoms had improved with a plan to continue

TB quadruple therapy and a weaning regime of steroids (10 mg every 5 days). At

subsequent outpatient appointments in the TB clinic, he was noted to be making

good recovery. He started gaining weight and appetite returned to normal. His

pleural and pericardial effusions also improved and this reflected in

improvement in his cough and breathing. His cervical and supraclavicular nodes

had also shrunk in repeat imaging. Six weeks into his anti-TB treatment when he

was on 10mg prednisolone, his symptoms relapsed and he developed further

anorexia, weight loss and fatigue. At this stage he also experienced

significant shortness of breath on minimal exertion and orthopnea. He was

thereafter reviewed in the cardiology clinic as an outpatient and was noted to

be short of breath at rest (Respiratory Rate (RR)-24) and remained tachycardic

(120bpm) but normotensive with a positive Kussmauls sign, suggesting limited

right ventricular filling. An immediate trans-thoracic echocardiogram was

performed which showed a recurrence of his pericardial effusion (1.5 cm

globally) with semi-fibrinous material and progression of his constrictive

physiology. As

well as the septal bounce and TDI patterns seen on the first echocardiogram,

there was now a dilated inferior vena at 3.3 cm cava with flow reversal into

the hepatic veins on color doppler imaging. The Left Ventricle (LV) remained

non-dilated and Ejection Fraction (EF) was preserved. The constrictive picture

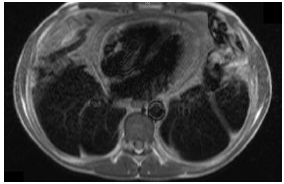

was later confirmed with cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging (cMRI) which

demonstrated circumferential thickening of the pericardium (13 mm) with

features of inflammation and constriction associated with a small pericardial

effusion and normal myocardium. The inferior vena cava and hepatic veins were

severely dilated. The left and right ventricles were noted to be small and he

had an LV EF of 70% on cMRI (Figure 2). Due

to a clinical relapse despite an extensive course of anti-TB treatment,

diagnosis was reconsidered with further differentials such as chronic infection

(toxoplasma, fungal, parasitic), haematological malignancy and systemic

autoimmune diseases and investigations performed accordingly. The prednisolone

dose was increased back to 50mg daily. TB treatment continued as diagnostic

uncertainty at that time, and the concern that if TB were a co-factor then

flare of this disease with immunosuppression may be potentially serious. Toxoplasma,

schistosoma and mycoplasma serology was negative and haematological malignancy

was unlikely based on the prior lymph node biopsy result. Malignancy markers

(AFP, CA125, CA19, CEA, HCG and PSA) were negative, and anti-IgG4 level was

normal. The autoimmune screen, however, revealed a positive Anti-Nuclear

Antibody (ANA) of 1:640 with a fine speckled pattern, positive anti-dsDNA with

a titer of 30, positive anti-Smith antibody and normal C3 and C4 levels. His

urine analysis showed trace of blood, and significantly raised urine protein:

creatinine ratio at 177 mg/mmol. In keeping with the American College of

Rheumatology (ACR) diagnostic criteria, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) was

then diagnosed based on the presence of pericarditis, proteinuria, positive ANA

and anti-dsDNA Ab. The prednisolone dose was increased to 60 mg (30 mg

equivalent due to Rifampicin) and hydroxychloroquine was initiated. Upon

discussion with Cardiology, 0.5 mg colchicine twice daily was also started for

symptomatic relief of constrictive pericarditis. After months of treatment, his

fatigue and systemic symptoms had improved, but he remained symptomatic from

constrictive effusive pericarditis, with ongoing symptoms and signs of right

sided heart failure. A

subsequent uncomplicated pericardiectomy was performed, which resulted in a

complete resolution of the signs of right sided heat failure and shortness of

breath. Pericardial biopsy results showed granulomatous inflammation and

fibrosis; TB cultures were negative. A subsequent renal biopsy showed features

of membranous lupus nephritis. A repeat echocardiogram following the procedure

showed mild septal bounce with no effusion but preserved biventricular function

and normal sized ventricles, consistent with a significant resolution of his

constrictive physiology post pericardiectomy (Figure 3). To

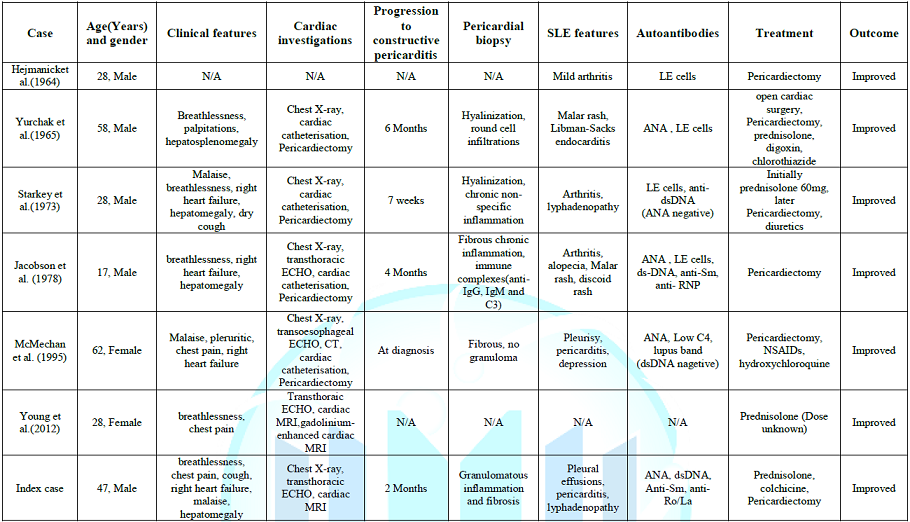

the best of our knowledge, only six cases of systemic lupus erythematosus with

constrictive pericarditis have been reported in English literature. Of these,

four patients were male and two female, with a median age of 38 years (range

17-58 years). Only two patients had a prior diagnosis of SLE and TB was part of

the differential diagnosis in at least five cases. The progression from

exudative pericarditis to constrictive pericarditis ranged from one week to six

months and some authors postulated that it might have been triggered by rapid

reduction of prednisolone dose. Only one of these six cases had an

effusive-constrictive pericarditis similar to our case. The diagnosis of

constrictive pericarditis was confirmed by echocardiography, right ventricular

catheterization or cardiac MRI (Table 1)

[1-7]. Five

of six patients underwent pericardiectomy and pericardial biopsy reports were

described in four cases. Overall, the histopathological findings were

non-specific: two biopsies showed hyalinization and either round-cell

infiltration or non-specific inflammation, other two demonstrated fibrosis with

inflammation but no granulomas [2,4-6]. Immunohistochemistry was performed in

the case described by Jacobson et al. [2] and it revealed the presence of

anti-IgG, IgM and C3 in pericardial tissue. Our patient is the only case that

demonstrated granulomatous inflammation and fibrosis; still the TB cultures

were negative. Cardiac symptoms resolved with steroid treatment alone in only

one case; in five patients, as well as in our patient, pericardiectomy was

performed leading to symptoms resolution [3]. All patients survived. Although

the most common causes of constrictive pericarditis are infectious or

idiopathic, this case highlights that underlying connective tissue diseases

should also be considered as a differential diagnosis, especially in those

cases with no proven etiology and without improvement with antimicrobial or

antiviral treatment. Although constrictive pericarditis is a rare feature in

SLE, a high index of suspicion is needed in patients who have worsening

shortness of breath despite a normal initial echocardiogram. In such cases, a

Cardiology opinion and cardiac MRI may be of value in identifying underlying

complications. Although it is difficult to make conclusions regarding gender

prevalence when only seven cases have been reported we note that five (71%) of

these patients were male; it is well-known that SLE has a female preponderance

though male patients with SLE often have more severe disease, which may account

for the higher proportion of male patients with constrictive pericarditis in

our literature review. In such patients with constrictive pericarditis, even

though corticosteroid treatment may partially alleviate the symptoms a Pericardiectomy

is likely to be required for definitive treatment. While a pericardial biopsy

might reveal non-specific features of acute or chronic inflammation, it should

be performed in all cases if possible, in order to exclude underlying

infection. 2. Jacobson

EJ and Reza MJ. Constrictive pericarditis in systemic lupus erythematosus.

Demonstration of immunoglobulins in the pericardium (1978) Arthritis Rheum 21: 972-974.

https://doi.org/10.1002/art.1780210815 3. Young

Oh J, Chang SA, Choe HY and Kim DK. Transient constrictive pericarditis in

systemic lupus erythematosus (2012) European Heart J Cardiovascular Imaging 13:

793. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jes052 4. Yurchak

PM, Levine SA and Gorlin R. Constrictive pericarditis complicating disseminated

lupus erythematosus (1965) Circulation 31: 113-118. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.31.1.113 5. Starkey

RH and Hahn BH. Rapid development of constrictive pericarditis in a patient

with systemic lupus erythematosus (1973) Chest 63:448-450. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.63.3.448 6.

Mcmechan

SR, McClements BM, McKeown PP, Webb SW and Adgey AA. Systemic lupus

erythematosus presenting as effuso-constrictive pericarditis (1995)

Postgraduate Medical J 71: 627-629. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.71.840.627 7. Hejmancik

MR, Wright JC and Quint R. The cardiovascular manifestations of systemic lupus

erythematosus (1964) American Heart J 68: 119-130. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-8703(64)90248-0 Hannah Jethwa, Department of Rheumatology,

Addenbrookes Hospital, Cambridge, United Kingdom, Tel: +01223 217457 E-mail: hannahjethwa@nhs.net Jethwa H, Rana M,

Kitt J, Menzies S, Steuer A, et al. Constrictive pericarditis as the first

presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus (2019) Rheumatic Dis Treatment J 1:

10-12. Lupus, Autoimmune disease, Bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy,Cardiovascular examination.Constrictive Pericarditis as the First Presentation of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Abstract

Full-Text

Case Summary

Discussion

Conclusion

References

*Corresponding author

Citation

Keywords