Review Article :

Fred Saleh and Ghassan Mouhanna Purpose:

The purpose of this study is to survey the existence of specialized pain

clinics/services in rural Lebanon. It also aims at highlighting the importance

of the existence of such clinics/services rurally. Method:

A review of the literature about pain in Lebanon was conducted using PubMed,

Medline, Google Scholars, and Research Gate. Another search was conducted using

Google Maps to locate any specialized pain clinics in the rural areas. The

Lebanese Society for Pain Medicine was also contacted for information about the

distribution of specialized pain clinics/services in Lebanon. Results: Our results

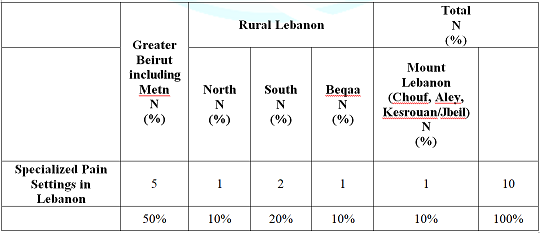

showed that the total number of pain clinics/services in Lebanon is ten. They

are distributed as follows: Five in Greater Beirut including Metn (50%), one in

North Lebanon (10%), two in South Lebanon (20%), one in Beqaa (10%), and one in

Mount Lebanon (Chouf, Aley, Kesrouan/Jbeil) (10%). The majority (90%) of these

services are hospital-based and are governed by the Anesthesia Departments.

Moreover, a comprehensive palliative care approach towards pain management in

terminally-ill cancer and non-cancer patients is still lacking nationwide. Among

such proper health services comes the importance of the existence of

specialized pain clinics in the rural settings. This is based on the fact that

the majority of the rural populations are farmers or technicians, jobs that are

often physically demanding and have high risks of strenuous physical injuries,

let alone exposure to hazardous chemicals. Adding to such risks is the

continuous mental pre-occupation by the

idea of financial survival in the rural villages, which make the rural

residents end up seeking help in relation to not only physical

pain but also to psychosomatic one. Pain is a natural phenomenon. It acts

as an alarming sign that something is going wrong inside our body, or could

occur as a consequence of exposure to thermal, chemical, or physical injuries.

Chronic pain is more than simply an unpleasant physical feeling. It brings one

down on an emotional level too. In fact, one of the main reasons behind

depression is chronic pain, which makes the sufferer goes into a vicious cycle,

whereby chronic pain leads to depression and the latter in turn increases the

perception of the pain. The end product is damage to both mental and physical

health. Globally, 8 of the 12 most disabling conditions are related either to

chronic pain or to the psychological

conditions strongly associated with persistent pain [13]. Non-malignant

chronic pain is one of the most common reasons for primary care visits in

urban cities, let alone in rural areas. However, rural areas do also have

health care disparities, which add to the problem itself. Such disparities have

been documented in relation to culture, beliefs, access to health care,

socioeconomic status, gender, and race. They even have influenced pain

management, since rurality as a social determinant of health has influenced

opioid prescribing [14]. In

a small country like Lebanon, where more than half of the population lives

outside the capital city Beirut, the availability of and

accessibility to specialized pain clinics in rural areas remain a major health

concern. According to the 2017 statistics, the population in Lebanon reached

6,229,794 [15]. This includes around 1.5 million Syrian refugees, and another

half-a-million Palestinian refugees. Rural

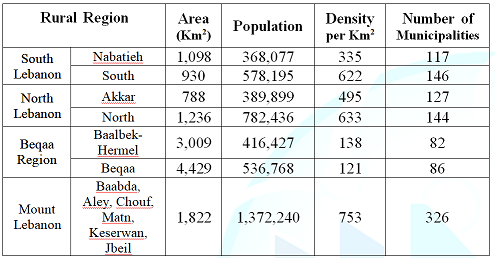

Lebanon is made of four main geographic regions, namely South Lebanon,

North Lebanon, Bekaa, and Mount Lebanon (Table

1). We aimed in this study at surveying the existence of specialized pain

clinics/services in rural Lebanon, and at reflecting on the importance of the

availability of such clinics/services rurally. Table

1: Distribution of Rural regions in Lebanon, and their

Demographics. Materials and

Methods PubMed,

Medline, Google Scholars, and Research Gate were the four search engines used.

We conducted separate searches using a combination of any of the following MeSH

terms “pain, pain clinic, pain intervention, palliative care, migraine,

headache, low back pain, neck pain, shoulder pain, fibromyalgia,

musculoskeletal pain, psychosomatic pain, osteoporotic pain, neuropathic

pain, non-neoplastic pain, neoplastic pain, cancer pain, pediatric pain,

elderly pain”, and “Lebanon”. We searched for such MESH terms in the title

and/or abstracts of the published articles. We then filtered the articles based

on those pertaining to human studies and published in English. No time-frame

was used to filter out old versus new publications. Google Maps was used as a

GIS engine to locate any specialized pain clinic in the rural areas. The

Lebanese Society for Pain Medicine was finally contacted to confirm the results

obtained by Google Maps about the distribution of specialized pain

clinics/services in Lebanon. Our

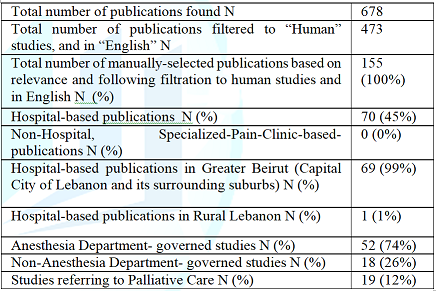

literature search revealed 678 publications that included one or more of the

MeSH terms described in the Materials and Methods section (Table 2). These publications were then filtered to human studies

and in English, followed by manual selection based on relevance of the selected

publications there were 70 hospital-based pain studies (45%), as compared to

none in non-hospital-based specialized-pain clinics (0%). The majority (99%) of

these 70 publications were conducted in Greater Beirut (Beirut City and the

surrounding suburbs), as compared to one study (1%) conducted in Rural Lebanon.

The Anesthesia specialty governed 74% of these studies, as compared to 26%

conducted under other medical or surgical departments. There were 19

publications (12%) referring to palliative care.Our

results also showed that there are currently ten specialized pain settings in

Lebanon. Greater Beirut (Capital City and surrounding suburbs, including Metn)

hosts 50% of these settings, while the remaining ones are distributed in Rural

Lebanon as follows: 1% in North Lebanon, 2% in South Lebanon, 1% in Beqaa, and

1% in Mount Lebanon (Chouf, Aley, Kesrouan/Jbeil) (Table 3). Note: Search engines used PubMed,

Medline, Google Scholars, and Research Gate. Table 2: Publications

about pain in Lebanon. Table

3: Distribution of Specialized Pain

Settings in Lebanon.. Discussion There

were a few striking and surprising features observed in this study. First,

specialized pain clinics or polyclinics are still lacking in Lebanon.

Second, pain management is still hospital-based, and is in the capital city and

its suburbs, leaving rural Lebanon underserved. Third, the majority of pain

management is still conducted through the Anesthesia

Department. Fourth, complementary, alternative and integrative medicine,

including palliative care, still has a long way to go in Lebanon. Fifth,

opioids analgesia for terminally ill cancer and non-cancer patients has not yet

been addressed efficiently by both the public health and legislation

authorities in the capital city Beirut, and the situation is even worse in

rural areas of Lebanon.

Lebanon is a small low-income country where a significant proportion of the

population reside outside the capital city, namely in the North, South, Beqaa,

and the mountain. Despite the continuous help and attempts of the international

community to develop such rural areas of Lebanon, proper and structurally

functional health care systems and services are still lacking. This becomes

more evident when referring to pain management, be it for inpatients or

outpatients. Pain in low- and

middle-income countries, and in rural areas Pain

is often classified as mild, moderate, severe, dull, sharp, localized, diffuse,

sudden, chronic, or as a combination of two or more. Regardless to which of

these categories it belongs, it remains an unpleasant sensation that affects

the rich and the poor, the educated and uneducated, the peasant and the senior

official, the baby, infant, adolescent, toddler, teenager, adult, and elderly.

It is a universal phenomenon regardless of the human race, religion, or

location on planet earth. However, what is different about pain in various

countries is how the health care system is set to alleviate such human

suffering, especially in rural underprivileged communities. In a study

conducted by Jackson and colleagues, the authors investigated the psychosocial

and demographic links with chronic pain solely from Low and Middle-Income

Countries (LMICs), and compared them with current data worldwide [13].

Correlation with rural/urban location, gender, age, education level, insomnia,

depression, anxiety, posttraumatic

stress, disability, income, and additional sites of pain was studied for

each type of chronic pain without clear etiology. Pain was reported in

association with disability in 50 publications, female gender in 40

publications, older age in 34 publications, depression in 36 publications,

anxiety in 19 publications, and multiple somatic complaints in 13 publications.

Females, old patients, and labors in low-education and low-income subgroups

were more likely to have pain in multiple sites, disabilities, and mood

disorders. The authors concluded that recognition

and management of pain are especially crucial in resource-poor geographic

locations like rural areas [13].

Recognition and management of pain in rural areas has also been addressed by a

recent study conducted by Katzman and colleagues through the ECHO Pain project

[16,17]. It is a creative telementoring program for health professionals, which

was created in 2009 at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center to

fill considerable gaps in pain management expertise in rural areas. Substantive

proceeding with instruction for clinicians who practice in provincial and

underserved networks assembles week after week by methods for telehealth

innovation. Demonstrations, case-based learning, and didactics are incorporated

into the inter-professional program to improve pain management in the primary

care setting. The project has proven to be a successful continuing professional

development program. The telementoring model seems to compensate for the large

knowledge gap in pain education seen in primary care and other settings.

Expertise is conveyed by implementing effective, work-based and evidence-based

education for diverse health professionals [16].

Living in rural areas, especially in poor countries, is often associated with

low income, stress, work-related injuries, and boredom, to name a few, leading

to psychological

distress, severity of medical illness and dysfunction in conjunction with

psychosomatic pain [18]. Thurston-Hicks and colleagues studied functional

impairment accompanying severity of medical illness and psychological distress

in rural primary care inhabitants, and investigated how such impairment

speckled with chronic medical illness and psychological distress. The authors

reported that the functional impairment was explicated more by psychological

distress than by severity of medical illness. They concluded that decreasing

the burden of psychological distress among primary care patients may improve

functioning [19]. Other studies investigated work-related injuries in rural

areas resulting in pain that is associated with musculoskeletal disorders

(MSDs) [6]. Antonopoulos and co-workers reported that MSDs were common in

patients attending the rural primary care centers in rural Greece, and were

associated with a poor quality of life and mental distress that affected their

consultation behavior [20]. The authors also reported that fewer patients seek

care than those who report symptoms [10]. Dunstan & Covic suggested that

independent, rural or community-based practitioners, working collaboratively

using an integrated treatment program, can yield optimistic results for pain-disabled

injured workers, and attain results similar to those conveyed by urban-based

pain clinics [21]. There

seems to be a shift in low-resource nations, whereby the third epidemiological

transition is becoming prevalent and is characterized by an increase in the

burden of non-communicable health issues. Headache and related disorders make

up a substantial proportion of such health issues. Population growth involving

youthful demographic, and significant rural-urban migration have been witnessed

in low-resource countries. Youthful demographic is often the natural cohort for

migraine, and socioeconomic mobility and modern lifestyle associated with

physical inactivity and obesity are all contributing to headache. Life

expectancy is rising in some resource-restricted countries. This upsurge the

incidence of secondary headache credited to neurovascular causes. Health care

services are chiefly designed to respond to infectious epidemic, and not to

evolving burden like headache,

especially in low-resource-restricted settings that often suffer from

ill-equipped regimes with malfunctioning health policies. As such, headache

treatment and the know-how are scarce in these countries. Addressing the

increasing burden of headache and related disorders in resource-limited

settings is essential to avoid disability, which in turn decreases the

socioeconomic performance in a young booming populace [22]. Palliative

care and the provision of pain relief medicine are essential components of

health care. Palliative care has been an evolving science, and a rapidly

growing specialty in medicine, nursing, and allied health professions in

first-world countries. Palliative care teams now consist of oncologists,

neurologists (pain specialists), palliative care nurse specialists,

complementary and alternative (integrative) medicine specialist (naturopathic

medicine), clinical pharmacists, clinical psychologists, and sociologists.

Palliative care was first identified as a need for terminally-ill cancer

patients, but has been evolving ever since to address chronic pain and related

comorbidity in non-cancer patients [23,24].

In rural areas, the elements that hinder the provision of palliative care

include inadequate access and readiness of pain medication, and providers link

of palliative care with end-of-life care. Satisfactory pain relief is often not

a priority in a busy health care setting. Guaranteeing patients receive

adequate relief for their pain requires interferences at both the clinical and

policy levels. This includes the continuous supply of needed pain medications,

and the training in palliative care for all providers [24].

Pain and depression are common and treatable symptoms among cancer patients,

but they are frequently undertreated and undetected either due to cost or

inexperience [18]. In a study conducted by the Indiana Cancer Pain and

Depression (INCPAD) trial aiming at exploring the incremental cost

effectiveness of the INCPAD intervention, the authors reported that telecare

management coupled with automated symptom monitoring can improve pain and

depression outcomes in cancer patients, and can be cost effective [25]. In

1998, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) surveyed its members to

evaluate the practices, challenges, and attitudes associated with end-of-life

care of cancer patients. Pediatric oncologists conveyed a deficiency in formal

courses in pediatric palliative care, and a need for strong role models in this

area. The lack of a reachable pain service or palliative care team was often

identified as a barrier to good care. Another identified hurdle was the

communication difficulty that exists between parents and oncologists,

especially regarding the shift to end-of-life care and adequate pain control.

Integration of palliative care into the routine care of the seriously ill

children through symptom control and psychosocial support has been put in place

[26]. Another

approach to palliative care that has been evolving as well is complementary and

alternative (integrative) medicine (CAM), which also includes herbal medicine

(naturopathic medicine). Although it is beyond the scope of this manuscript to

highlight the pros and cons of CAM, we limit this section to two important

studies for that matter. Guo and colleagues conducted a systematic review and

meta-analysis on the efficacy of injecting the compound Kushen (CKI) in

relieving cancer-related pain. Sixteen trials were identified with a total of

1564 patients. The total pain relief rate of CKI plus chemotherapy was better

than chemotherapy alone, except for colorectal cancer. The treatment groups

achieved a reduction in the incidences of leukopenia, as well as hepatic,

gastrointestinal, and renal functional lesions [27]. In another study conducted

by Denneson and co-workers, the authors reported on prior use and willingness

to try CAM among 401 veterans experiencing chronic non-cancer pain, and

explored the differences between CAM users and nonusers. Participants, who were

recruited in a randomized controlled trial of a collaborative intervention for

chronic pain from five Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) primary care

clinics, self-reported prior use and willingness to try CAM. The authors

detected few differences between veterans who had tried CAM and those who had

not, suggesting that CAM may have broad appeal among veterans with chronic pain

[28]. Opioid

therapy is often controversial and debatable when it comes down to prescription

[29-31]. This is usually due to fear of abuse and addiction. However, the rules

have been more lenient in the past decade, especially when dealing with pain in

terminally-ill cancer patients, but predominantly in the urban and not in the

rural areas. The universal framework to be yet established for using opioids

for chronic pain that is not associated with cancer remains to be seen in both

geographic areas as well. For clinicians, using opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer

pain (CNCP) often results in a conflict between treating their patients pain

and fears of diversion of medication, legal action, or addiction. These

consequent stresses on clinical encounters might in turn unfavorably affect

some elements of clinical care. Buckley and co-workers evaluated a possible

association between Chronic

Opioid Therapy (COT) for CNCP and receipt of various preventive services.

The authors found that patients using COT for CNCP were less likely to receive

some preventive services, such as cancer and lipid profile screening and

smoking cessation counseling [32]. Studies elsewhere have shown that rural

citizens with persistent ache are much more likely to receive an opioid

prescription than non-rural residents. Opioids were taken for pain alleviation

through 76% of the rural citizens, as compared with 52% of the non-rural

residents [33]. Pain Specialists There

are still some debates about the identification of the pain

specialist, including his/her training background, specialty, and

professional and career development in relation to pain management [34]. In a

study conducted by Breuer and colleagues, the authors determined the profiles

of the board-certified pain physician workforce, and the profiles of those

residing near medical pain practices [35]. The 750 respondents were similar to

the entire board-certified group in geographic distribution, age, and primary

specialty. Pain practices were found to be underrepresented in rural areas. The

majority of pain physicians treated chronic pain; 31% worked in an academic

environment; 84% followed patients longitudinally; 29% focused on a single

modality; and 50% had an interdisciplinary practice. Academics were more likely

to be neurologists,

and to have had a pain fellowship. Modality-oriented practitioners were more

likely to be anesthesiologists, and were less likely to provide training to

fellows, follow patients with chronic pain longitudinally, require an opioid

contract, or prescribe controlled substances. The authors reported that

although boarded specialists could benefit from similar curricula and must pass

a certifying examination, their practices varied considerably. They

concluded that data are needed to further elucidate the nature of workforce

disparity, its impact on patient care, and the role of other pain management

clinicians [35]. Other

studies demonstrated that a Clinical

Pathway (CP) enhances pain management in palliative care. However, studies

on CPs in home palliative care, especially in rural areas, are little.

Physicians performing palliative care in rural areas frequently face

characteristic difficulties, and CP could be an effective tool to overcome such

difficulties. Moreover, it could improve adherence to the pain management

guidelines set by WHO [36]. The

specialized pain clinic The emergence of pain specialists, and his/her

integration in the palliative care team as being an essential member who could

function with the team inside and outside the hospital boundaries have led to

the establishment of specialized pain clinics in first world countries. Such

clinics are venues where patients from all age groups irrespective of the

etiology of their pain, be it medical, surgical, orthopedic, traumatic,

oncological, etc., are examined and treated. Visitors of these clinics include

patients with cancer, back pain and radiculopathy, acute herpes zoster and post

herpetic pain, facial neuralgias (trigeminal, occipital, others), painful

peripheral neuropathy (diabetic, drug induced after chemotherapy and

anti-tubercular treatment), headaches including migraine, central pain

syndromes (deafferentation pain) of stroke, phantom limb pain and

post-amputation stump pain, chronic pelvic pain particularly in women,

myofascial and head and neck pain syndromes, fibromyalgias, unusual pain

conditions like HIV, etc. [21,37-50]. We

attempted in this study to shed the light on a universal phenomenon that could

strike anybody, anytime, anywhere, and that is pain. Pain management in Lebanon

still needs proper organization and legislation at various levels. Pain

management protocols should be established for inpatients and outpatients,

and should be unified across the country. Special efforts should be targeted

towards establishing specialized pain polyclinics, and rural areas should be

given upmost priority. Palliative care, be it for cancer or non-cancer patients

with chronic pain, should be a priority, and lessons learned from worldwide

studies should be used to shorten the time frame needed to establish the system

in Greater Beirut, and in the rural areas of Lebanon, namely North, South,

Beqaa, and the Mountain. 1.

Feinberg

T, Jones DL, Lilly C, Umer A and Innes K. The Complementary Health Approaches

for Pain Survey (CHAPS): validity testing and characteristics of a rural

population with pain (2018) PLoS One 13:1-20. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196390 2.

Anderson

FWJ, Naik SI, Feresu SA, Gebrian B, Karki M, et al. Perceptions of pregnancy

complications in Haiti (2008) Int J Gynaecol Obstet 100: 116-123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.08.005 3.

Gorain

A, Barik A, Chowdhury A and Rai RK. Preference in place of delivery among rural

Indian women (2017) PLoS One 12:1-11. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190117 4.

Osaka

R and Nanakorn S. Health care of villagers in northeast Thailand--a health

diary study (1996) Kurume Med J 43: 49-54. https://doi.org/10.2739/kurumemedj.43.49 5.

Dickstein

Y, Neuberger A, Golus M and Schwartz E. Epidemiologic profile of patients seen

in primary care clinics in an urban and a rural setting in Haiti, 2010-11

(2014) Int Health 6:258-262. https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihu033 6.

Liu

Y, Zhang H, Liang N, Fan W, Jun Li, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of

knee osteoarthritis in a rural Chinese adult population: an epidemiological

survey (2016) BMC Public Health 16:94. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2782-x 7.

Davatchi

F. Rheumatology in Iran (2009) Int J Rheum. Dis 12:283-287. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-185X.2009.01425.x 8.

McGraw

IT, Dhanani N, Ray LA, Bentley R.M, Bush R.L, et al. Rapidly evolving outbreak

of a febrile illness in rural haiti: the importance of a field diagnosis of chikungunya

virus in remote locations (2015) Vector borne zoonotic Dis 15:678-682. https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2014.1763 9.

Osmun,

WE, Copeland J, Parr J, Boisvert L. Characteristics of chronic pain patients in

a rural teaching practice (2011) Can Fam Phy 57:436-440. 10.

Antonopoulou

M, Antonakis N, Hadjipavlou A and Lionis C. Patterns of pain and consulting

behaviour in patients with musculoskeletal disorders in rural Crete, Greece

(2007) Fam Pract 24:209-216. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmm012 11.

Lionis

CD, Vardavas CI, Symvoulakis EK, Papadakaki MG, Anastasiou FS, et al. Measuring

the burden of herpes zoster and post herpetic neuralgia within primary care in

rural Crete, Greece (2011) BMC Fam Pract 12:136. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-12-136 12.

Benesh

LR, Szigeti E, Ferraro FR, Gullicks JN. Tools for assessing chronic pain in

rural elderly women (1997) Home Health Nurse 15:207-211. 13.

Jackson

T, Thomas S, Stabile V, Han X, Shotwell M, et al. Chronic pain without clear

etiology in low- and middle-income countries: a narrative review (2016) Anesth

Analg 122:2028-2039. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000001287 14.

Prunuske

JP, St Hill CA, Hager KD, Lemieux AM, Swanoski MT, et al. Opioid prescribing

patterns for non-malignant chronic pain for rural versus non-rural US adults: a

population-based study using 2010 NAMCS data (2014) BMC Health Serv Res 14:563.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-014-0563-8 15.

World

population prospects: The 2017 revision (2017) Department of economic and social

affairs, Population division volume II: Demographic profiles, UN, New York,

USA. 16.

Katzman

JG. Innovative telementoring for pain management: project ECHO pain. (2014) J

Contin. Educ Health Prof 34:68-75. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.21210 17.

Shelley

BM, Katzman JG, Comerci GD Jr, Duhigg DJ, Olivas C, et al. ECHO pain

curriculum: balancing mandated continuing education with the needs of rural

health care practitioners (2017) J Contin Educ Health Prof 37:190-194. https://doi.org/10.1097/CEH.0000000000000165 18.

Thommasen

HV, Baggaley E, Thommasen C and Zhang W. Prevalence of depression and

prescriptions for antidepressants, Bella Coola Valley, 2001 (2005) Can J Psych

50:346-352. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370505000610 19.

Thurston-Hicks

A, Paine S, Hollifield M. Functional impairment associated with psychological

distress and medical severity in rural primary care patients (1998) Psychiatr

Serv 49:951-955. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.49.7.951 20.

Antonopoulou,

Maria D, Alegakis, Athanasios K, Hadjipavlou, et al. Studying the association

between musculoskeletal disorders, quality of life and mental health. A primary

care pilot study in rural Crete, Greece (2009) BMC musculoskeletal disord 10:143.

https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-10-143 21.

Dunstan

DA and Covic T. Can a rural community-based work-related activity program make

a difference for chronic pain-disabled injured workers? (2007) Aust J Rural

Health 15:166-171. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1584.2007.00879.x 22.

Woldeamanuel

YW. Headache in Resource-limited settings (2017) Curr pain and headache reports

21:51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-017-0651-7 23.

Denneson

LM, Corson K, Dobscha SK. Complementary and alternative medicine use among

veterans with chronic noncancer pain (2011) J Rehabil Res Dev 48:1119-1128. 24.

Dekker

AM, Amon JJ, le Roux KW, Gaunt CB. What is killing me most: chronic pain and

the need for palliative care in the Eastern Cape, South Africa (2012) J Pain

Palliat Care Pharmacother 26:334-340. https://doi.org/10.3109/15360288.2012.734897 25.

Choi

Yoo SJ, Nyman JA, Cheville AL and Kroenke K. Cost effectiveness of telecare

management for pain and depression in patients with cancer: results from a

randomized trial (2014) Gen Hosp Psychi 36:599-606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.07.004 26.

Hilden

JM, Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Link MP, Foley KM, et al. Attitudes and

practices among pediatric oncologists regarding end-of-life care: results of

the 1998 American Society of Clinical Oncology survey (2001) J Clin. Oncol 19:205-212. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.205 27.

Guo

YM, Huang YX, Shen HH, Sang XX, Ma X, et al. Efficacy of compound kushen

injection in relieving cancer-related pain: a systematic review and

meta-analysis (2015) Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 84:7-42. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/840742 28.

Denneson

LM, Corson K and Dobscha SK. Complementary and alternative medicine use among

veterans with chronic non-cancer pain (2011) J Rehab Res Dev 46:1119-1128. 29.

Click

IA, Basden JA, Bohannon JM, Anderson H and Tudiver F. Opioid prescribing in

rural family practices: a qualitative study (2018) Subst Use Misuse 53:533-540.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2017.1342659 30.

Buckley

DI, Calvert JF, Lapidus JA and Morris CD. Chronic opioid therapy and preventive

services in rural primary care: an Oregon rural practice-based research network

study (2010) Ann Fam Med 8:237-244. https://dx.doi.org/10.1370%2Fafm.1114 31.

Westanmo

A, Marshall P, Jones E, Burns K, Krebs EE. Opioid dose reduction in a VA health

care system implementation of a primary care population-level initiative (2015)

Pain Med 16:1019-1026. https://doi.org/10.1111/pme.12699 32.

Buckley,

David I, Calvert, James F, Lapidus, et al. Chronic opioid therapy and

preventive services in rural primary care: an Oregon rural practice-based

research network study (2010) Annals fam med 8:237-244. https://dx.doi.org/10.1370%2Fafm.1114 33.

Eaton

LH, Langford D, Meins A, Rue T, Tauben DJ, et al. Use of self-management

interventions for chronic pain management: a comparison between rural and

non-rural residents (2018) Pain Manag Nurs 19:8-13. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.pmn.2017.09.004 34.

Buenaventura

RM, McSweeney TD, Benedetti C, Severyn SA and Gravlee G P. The qualifications

of pain physicians in Ohio (2005) Anesth Analg 100:1746-1752. https://doi.org/10.1213/01.ANE.0000152185.81114.01 35.

Breuer

B, Pappagallo M, Tai JY, Portenoy RK. US board-certified pain physician

practices: uniformity and census data of their locations (2007) J Pain 8:244-250.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2006.08.009 36.

Tateno,

Yuki, Ishikawa and Shizukiyo. Clinical pathways can improve the quality of pain

management in home palliative care in remote locations: retrospective study on

Kozu Island, Japan (1992) Rural and remote health. 37.

ryce

DA, Nelson Glurich JI and Berg RL. Intradiscal electro thermal annuloplasty

therapy: a case series study leading to new considerations (2005) WMJ 104: 39-46. 38.

Chalkiadis

GA. Management of chronic pain in children (2001) Med J Aust 175:476-479. 39.

Pain

relief clinic celebrates 15 years (2014) BDJ 216:608.

https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.460 40.

Venzke

L, Calvert JF Jr, Gilbertson B. A randomized trial of acupuncture for vasomotor

symptoms in post-menopausal women (2010) Complement. Ther Med.18:59-66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2010.02.002 41.

Gooch

K, Marshall DA, Faris PD, Khong H, Wasylak T, et al., Comparative effectiveness

of alternative clinical pathways for primary hip and knee joint replacement

patients: a pragmatic randomized, controlled trial (2012) Osteoarthr Cartil 20:1086-1094.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2012.06.017 42.

Linnemayr

S, Glick P, Kityo C, Mugyeni P and Wagner G. Prospective cohort study of the

impact of antiretroviral therapy on employment outcomes among HIV clients in

Uganda (2013) AIDS Patient Care STDS 27:707-714. Corresponding author:Fred

Saleh, College of Public Health, Phoenicia

University, District of Zahrany, South Lebanon, Lebanon, E-mail: fred.saleh@pu.edu.lb Specialized pain clinic, Rural health, Lebanon.Specialized Rural Pain Clinics:Lessons for a Small Country like Lebanon

Abstract

Background:

People with chronic pain and who live in rural communities often lack access to

pain specialists. They end up relying on primary care providers who may be less

prepared to deal with their conditions.

Full-Text

Introduction

Rural

areas have exceptional health deliberations that eventually consequence in

persistent health discrepancies in outcomes [1-5]. These discrepancies occur

both when comparing urban to rural groups, and when comparing rural subgroups

to each other. Rural communities tend to have unique health

problems, economic concerns, demographic characteristics, resource

shortages, and cultural behaviors that culminate together and thus affect the

health of the residents [1,2,6-12]. Three of the most urgent challenges faced

by rural residents are poverty, education, and access to proper health

services.

Results

Migraine

Palliative

Care

Opioid Therapy

The clinic should be equipped with fluoroscopy for pinpointing accuracy of the

nerve blocks, nonionic radioopaque dyes, steroids like triamcinolone or

depomedrol that have a slow release formulation which sustains the anti-inflammatory

effect for two to three months to ensure that the nerve heals over that time, a

safe technique like radiofrequency for denervation instead of neurolytic agents

like phenol and alcohol which can give rise to neuropathic pain by themselves,

implants like spinal cord stimulators for treating the pain of chronic

backache, refractory angina, failed back surgery etc., intrathecal pumps

tunneled subcutaneously to a pouch in the front of abdomen for other types of

chronic pain and cancer pain, discography to pinpoint the intervertebral disc

to be removed thereby avoiding failure of back surgery, needle procedures like Intra

Discal Electro-thermal annuloplasty (IDET), and nucleoplasty to replace major

invasive back surgery. Conclusion

References

Citation: Saleh F and

Mouhanna G. Specialized rural pain clinics:

lessons for a small country like Lebanon (2019)

Neurophysio and Rehab 1: 6-11 Keywords